School Show Study Guide

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1St Annual Dreams Come True Feis Hosted by Central Florida Irish Dance Sunday August 8Th, 2021

1st Annual Dreams Come True Feis Hosted by Central Florida Irish Dance Sunday August 8th, 2021 Musician – Sean Warren, Florida. Adjudicator’s – Maura McGowan ADCRG, Belfast Arlene McLaughlin Allen ADCRG - Scotland Hosted by - Sarah Costello TCRG and Central Florida Irish Dance Embassy Suites Orlando - Lake Buena Vista South $119.00 plus tax Call - 407-597-4000 Registered with An Chomhdhail Na Muinteoiri Le Rinci Gaelacha Cuideachta Faoi Theorainn Rathaiochta (An Chomhdhail) www.irishdancingorg.com Charity Treble Reel for Orange County Animal Services A progressive animal-welfare focused organization that enforces the Orange County Code to protect both citizens and animals. Entry Fees: Pre Bun Grad A, Bun Grad A, B, C, $10.00 per competition Pre-Open & Open Solo Rounds $10.00 per competition Traditional Set & Treble Reel Specials $15.00 per competition Cup Award Solo Dances $15.00 per competition Open Championships $55.00 (2 solos are included in your entry) Championship change fee - $10 Facility Fee $30 per family Feisweb Fee $6 Open Platform Fee $20 Late Fee $30 The maximum fee per family is $225 plus facility fee and any applicable late, change or other fees. There will be no refund of any entry fees for any reason. Submit all entries online at https://FeisWeb.com Competitors Cards are available on FeisWeb. All registrations must be paid via PayPal Competitors are highly encouraged to print their own number prior to attending to avoid congestion at the registration table due to COVID. For those who cannot, competitor cards may be picked up at the venue. For questions contact us at our email: [email protected] or Sarah Costello TCRG on 321-200-3598 Special Needs: 1 step, any dance. -

The Frothy Band at Imminent Brewery, Northfield Minnesota on April 7Th, 7- 10 Pm

April Irish Music & 2018 Márt Dance Association Márta The mission of the Irish Music and Dance Association is to support and promote Irish music, dance, and other cultural traditions to insure their continuation. Inside this issue: IMDA Recognizes Dancers 2 Educational Grants Available Thanks You 6 For Irish Music and Dance Students Open Mic Night 7 The Irish Music and Dance Association (IMDA) would like to lend a hand to students of Irish music, dance or cultural pursuits. We’re looking for students who have already made a significant commitment to their studies, and who could use some help to get to the next level. It may be that students are ready to improve their skills (like fiddler and teacher Mary Vanorny who used her grant to study Sligo-style fiddling with Brian Conway at the Portal Irish Music Week) or it may be a student who wants to attend a special class (like Irish dancer Annie Wier who traveled to Boston for the Riverdance Academy). These are examples of great reasons to apply for an IMDA Educational Grant – as these students did in 2017. 2018 will be the twelfth year of this program, with help extended to 43 musicians, dancers, language students and artists over the years. The applicant may use the grant in any way that furthers his or her study – help with the purchase of an instrument, tuition to a workshop or class, travel expenses – the options are endless. Previous grant recipients have included musicians, dancers, Irish language students and a costume designer, but the program is open to students of other traditional Irish arts as well. -

Katie Martin

Katie Martin Some fact´s at first… When and where were you born? I was born in Coventry, England on the 1st of September 1980. Your height? 5’ 7 ½ . What is your favourite food? Seafood and Pasta Your favourite music? Chart music and R´and´ B. Joss Stone, maroon 5, Lucie Silvas, Kelly Clarckson, etc. Your favourite movie? „Notting Hill“, „My best friends Wedding“, „Stepmom“. Julia Roberts is my favourite actress. Your favourite city / place in the world, you have visited so far? Cape town in South Africa is my most favourite place in the whole world. Do you have any hidden talents, we don’t know about? I have a Diploma in make up artistory for film and television. What’s the most treasured moment in your life, so far? My most treasured moment in the Show is dancing in Hyde Park with Feet of Flames and also performing Lead for the first time. About your family… Please tell us something about your parents - what do they do for their living? Do they dance as well? My dad is an engineer and my mom is a nurse. My mum is also an amazing Irish Dancing teacher and was my very first teacher. Do you have any brothers or sisters? How old are they? Do they dance, too? What do they do for their living? My brothers name is Thomas and he is 23 years old. He is also in Troupe 1. Is it hard for you, to be apart from your family for such a long time while touring? How often are you able to travel back home again? It can be hard but because we have been touring for so many years we´re use to it now. -

2010–2011 Season Sponsors

2010–2011 SEASON SPONSORS The City of Cerritos gratefully thanks our 2010–2011 Season Sponsors for their generous support of the Cerritos Center for the Performing Arts. YOUR FAVORITE ENTERTAINERS, YOUR FAVORITE THEATER If your company would like to become a Cerritos Center for the Performing Arts sponsor, please contact the CCPA Administrative Offices at 562-916-8510. THE CERRITOS CENTER FOR THE PERFORMING ARTS (CCPA) thanks the following CCPA Associates who have contributed to the CCPA’s Endowment Fund. The Endowment Fund was established in 1994 under the visionary leadership of the Cerritos City Council to ensure that the CCPA would remain a welcoming, accessible, and affordable venue in which patrons can experience the joy of entertainment and cultural enrichment. For more information about the Endowment Fund or to make a contribution, please contact the CCPA Administrative Offices at (562) 916-8510. Benefactor Jill and Steve Edwards Ilana and Allen Brackett Erin Delliquadri $50,001-$100,000 Dr. Stuart L. Farber Paula Briggs Ester Delurgio José Iturbi Foundation William Goodwin Scott N. Brinkerhoff Rosemarie and Joseph Di Giulio Janet Gray Darrell Brooke Rosemarie diLorenzo Sandra and Bruce Dickinson Patron Rosemary Escalera Gutierrez Mary Brough Marianne and Bob Hughlett, Ed. D. Joyce and Russ Brown Amy and George Dominguez $20,001-$50,000 Robert M. Iritani Dr. and Mrs. Tony R. Brown Mrs. Abiatha Doss Bryan A. Stirrat & Associates Dr. HP Kan and Mrs. Della Kan Cheryl and Kerry Bryan Linda Dowell National Endowment for the Arts Jill and Rick Larson Florence P. Buchanan Robert Dressendorfer Eleanor and David St. -

Traditional Irish Music Presentation

Traditional Irish Music Topics Covered: 1. Traditional Irish Music Instruments 2 Traditional Irish tunes 3. Music notation & Theory Related to Traditional Irish Music Trad Irish Instruments ● Fiddle ● Bodhrán ● Irish Flute ● Button Accordian ● Tin/Penny Whistle ● Guitar ● Uilleann Pipes ● Mandolin ● Harp ● Bouzouki Fiddle ● A fiddle is the same as a violin. For Irish music, it is tuned the same, low to high string: G, D, A, E. ● The medieval fiddle originated in Europe in ● The term “fiddle” is used the 10th century, which when referring to was relatively square traditional or folk music. shaped and held in the ● The fiddle is one of the arms. primarily used instruments for traditional Irish music and has been used for over 200 years in Ireland. Fiddle (cont.) ● The violin in its current form was first created in the early 16th century (early 1500s) in Northern Italy. ● When fiddlers play traditional Irish music, they ornament the music with slides, cuts (upper grace note), taps (lower grace note), rolls, drones (also known as a double stop), accents, staccato and sometimes trills. ● Irish fiddlers tend to make little use of vibrato, except for slow airs and waltzes, which is also used sparingly. Irish Flute ● Flutes have been played in Ireland for over a thousand years. ● There are two types of flutes: Irish flute and classical flute. ● Irish flute is typically used ● This flute originated when playing Irish music. in England by flautist ● Irish flutes are made of wood Charles Nicholson and have a conical bore, for concert players, giving it an airy tone that is but was adapted by softer than classical flute and Irish flautists as tin whistle. -

2014–2015 Season Sponsors

2014–2015 SEASON SPONSORS The City of Cerritos gratefully thanks our 2014–2015 Season Sponsors for their generous support of the Cerritos Center for the Performing Arts. YOUR FAVORITE ENTERTAINERS, YOUR FAVORITE THEATER If your company would like to become a Cerritos Center for the Performing Arts sponsor, please contact the CCPA Administrative Offices at 562-916-8510. THE CERRITOS CENTER FOR THE PERFORMING ARTS (CCPA) thanks the following current CCPA Associates donors who have contributed to the CCPA’s Endowment Fund. The Endowment Fund was established in 1994 under the visionary leadership of the Cerritos City Council to ensure that the CCPA would remain a welcoming, accessible, and affordable venue where patrons can experience the joy of entertainment and cultural enrichment. For more information about the Endowment Fund or to make a contribution, please contact the CCPA Administrative Offices at (562) 916-8510. MARQUEE Sandra and Bruce Dickinson Diana and Rick Needham Eleanor and David St. Clair Mr. and Mrs. Curtis R. Eakin A.J. Neiman Judy and Robert Fisher Wendy and Mike Nelson Sharon Kei Frank Jill and Michael Nishida ENCORE Eugenie Gargiulo Margene and Chuck Norton The Gettys Family Gayle Garrity In Memory of Michael Garrity Ann and Clarence Ohara Art Segal In Memory Of Marilynn Segal Franz Gerich Bonnie Jo Panagos Triangle Distributing Company Margarita and Robert Gomez Minna and Frank Patterson Yamaha Corporation of America Raejean C. Goodrich Carl B. Pearlston Beryl and Graham Gosling Marilyn and Jim Peters HEADLINER Timothy Gower Gwen and Gerry Pruitt Nancy and Nick Baker Alvena and Richard Graham Mr. -

Pathetique Symphony New York Philharmonic/Bernstein Columbia

Title Artist Label Tchaikovsky: Pathetique Symphony New York Philharmonic/Bernstein Columbia MS 6689 Prokofiev: Two Sonatas for Violin and Piano Wilkomirska and Schein Connoiseur CS 2016 Acadie and Flood by Oliver and Allbritton Monroe Symphony/Worthington United Sound 6290 Everything You Always Wanted to Hear on the Moog Kazdin and Shepard Columbia M 30383 Avant Garde Piano various Candide CE 31015 Dance Music of the Renaissance and Baroque various MHS OR 352 Dance Music of the Renaissance and Baroque various MHS OR 353 Claude Debussy Melodies Gerard Souzay/Dalton Baldwin EMI C 065 12049 Honegger: Le Roi David (2 records) various Vanguard VSD 2117/18 Beginnings: A Praise Concert by Buryl Red & Ragan Courtney various Triangle TR 107 Ravel: Quartet in F Major/ Debussy: Quartet in G minor Budapest String Quartet Columbia MS 6015 Jazz Guitar Bach Andre Benichou Nonsuch H 71069 Mozart: Four Sonatas for Piano and Violin George Szell/Rafael Druian Columbia MS 7064 MOZART: Symphony #34 / SCHUBERT: Symphony #3 Berlin Philharmonic/Markevitch Dacca DL 9810 Mozart's Greatest Hits various Columbia MS 7507 Mozart: The 2 Cassations Collegium Musicum, Zurich Turnabout TV-S 34373 Mozart: The Four Horn Concertos Philadelphia Orchestra/Ormandy Mason Jones Columbia MS 6785 Footlifters - A Century of American Marches Gunther Schuller Columbia M 33513 William Schuman Symphony No. 3 / Symphony for Strings New York Philharmonic/Bernstein Columbia MS 7442 Beethoven: Symphony No. 9 in D minor Westminster Choir/various artists Columbia ML 5200 Tchaikovsky: Symphony No. 6 (Pathetique) Philadelphia Orchestra/Ormandy Columbia ML 4544 Tchaikovsky: Symphony No. 5 Cleveland Orchestra/Rodzinski Columbia ML 4052 Haydn: Symphony No 104 / Mendelssohn: Symphony No 4 New York Philharmonic/Bernstein Columbia ML 5349 Porgy and Bess Symphonic Picture / Spirituals Minneapolis Symphony/Dorati Mercury MG 50016 Beethoven: Symphony No 4 and Symphony No. -

2020 Syllabus

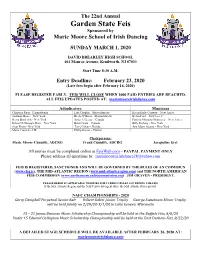

The 22nd Annual Garden State Feis Sponsored by Marie Moore School of Irish Dancing SUNDAY MARCH 1, 2020 DAVID BREARLEY HIGH SCHOOL 401 Monroe Avenue, Kenilworth, NJ 07033 Start Time 8:30 A.M. Entry Deadline: February 23, 2020 (Late fees begin after February 16, 2020) PLEASE REGISTER EARLY. FEIS WILL CLOSE WHEN 1000 PAID ENTRIES ARE REACHED. ALL FEIS UPDATES POSTED AT: mariemooreirishdance.com Adjudicators Musicians Christina Ryan - Pennsylvania Lisa Chaplin – Massachusetts Karen Early-Conway – New Jersey Siobhan Moore - New York Breda O’Brien – Massachusetts Kevin Ford – New Jersey Kerry Broderick - New York Jackie O’Leary – Canada Patricia Moriarty-Morrissey – New Jersey Eileen McDonagh-Morr – New York Brian Grant – Canada Billy Furlong - New York Sean Flynn - New York Terry Gillan – Florida Ann Marie Acosta – New York Marie Connell – UK Philip Owens – Florida Chairpersons: Marie Moore-Cunniffe, ADCRG Frank Cunniffe, ADCRG Jacqueline Erel All entries must be completed online at FeisWeb.com – PAYPAL PAYMENT ONLY Please address all questions to: [email protected] FEIS IS REGISTERED, SANCTIONED AND WILL BE GOVERNED BY THE RULES OF AN COIMISIUN (www.clrg.ie), THE MID-ATLANTIC REGION (www.mid-atlanticregion.com) and THE NORTH AMERICAN FEIS COMMISSION (www.northamericanfeiscommission.org) JIM GRAVEN - PRESIDENT. PLEASE REFER TO APPLICABLE WEBSITES FOR CURRENT RULES GOVERNING THE FEIS If the Mid-Atlantic Region and the NAFC have divergent rules, the Mid-Atlantic Rules prevail. NAFC CHAMPIONSHIPS - 2020 Gerry Campbell Perpetual -

Journal of Irish and Scottish Studies Cultural Exchange: from Medieval

Journal of Irish and Scottish Studies Volume 1: Issue 1 Cultural Exchange: from Medieval to Modernity AHRC Centre for Irish and Scottish Studies JOURNAL OF IRISH AND SCOTTISH STUDIES Volume 1, Issue 1 Cultural Exchange: Medieval to Modern Published by the AHRC Centre for Irish and Scottish Studies at the University of Aberdeen in association with The universities of the The Irish-Scottish Academic Initiative and The Stout Research Centre Irish-Scottish Studies Programme Victoria University of Wellington ISSN 1753-2396 Journal of Irish and Scottish Studies Issue Editor: Cairns Craig Associate Editors: Stephen Dornan, Michael Gardiner, Rosalyn Trigger Editorial Advisory Board: Fran Brearton, Queen’s University, Belfast Eleanor Bell, University of Strathclyde Michael Brown, University of Aberdeen Ewen Cameron, University of Edinburgh Sean Connolly, Queen’s University, Belfast Patrick Crotty, University of Aberdeen David Dickson, Trinity College, Dublin T. M. Devine, University of Edinburgh David Dumville, University of Aberdeen Aaron Kelly, University of Edinburgh Edna Longley, Queen’s University, Belfast Peter Mackay, Queen’s University, Belfast Shane Alcobia-Murphy, University of Aberdeen Brad Patterson, Victoria University of Wellington Ian Campbell Ross, Trinity College, Dublin The Journal of Irish and Scottish Studies is a peer reviewed journal, published twice yearly in September and March, by the AHRC Centre for Irish and Scottish Studies at the University of Aberdeen. An electronic reviews section is available on the AHRC Centre’s website: http://www.abdn.ac.uk/riiss/ahrc- centre.shtml Editorial correspondence, including manuscripts for submission, should be addressed to The Editors,Journal of Irish and Scottish Studies, AHRC Centre for Irish and Scottish Studies, Humanity Manse, 19 College Bounds, University of Aberdeen, AB24 3UG or emailed to [email protected] Subscriptions and business correspondence should be address to The Administrator. -

Toccata Classics TOCC0242 Notes

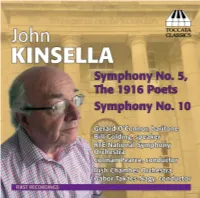

Americas, and from further aield: basically, if it’s good music and it hasn’t yet been recorded, JOHN KINSELLA, IRISH SYMPHONIST by Séamas da Barra John Kinsella was born in Dublin on 8 April 1932. His early studies at the Dublin College of Music were devoted to the viola as well as to harmony and counterpoint, but he is essentially self-taught as a composer. He started writing music as a teenager and although he initially adopted a straightforward, even conventional, tonal idiom, he began to take a serious interest in the compositional techniques of the European avant-garde from the early 1960s. He embraced serialism in particular as a liberating influence on his creative imagination, and he produced a substantial body of work during this period that quickly established him in Ireland as one of the most interesting younger figures of the day. In 1968 Kinsella was appointed Senior Assistant in the music department of Raidió Teilefís Éireann (RTÉ), the Irish national broadcasting authority, a position that allowed him to become widely acquainted with the latest developments in contemporary music, particularly through the International Rostrum of Composers organised under the auspices of UNESCO. But much of what he heard at these events began to strike him as dispiritingly similar in content, and he was increasingly persuaded that for many of his contemporaries conformity with current trends had become more P important than a desire to create out of inner conviction. As he found himself growing disillusioned with the avant-garde, his attitude to his own work began to change and he came to question the artistic validity of much of what he had written. -

CCN-BALLET DE LORRAINE Thu, Feb 16, 7:30 Pm Carlson Family Stage

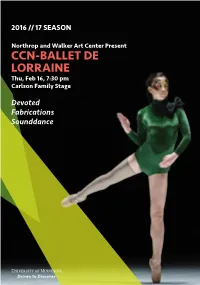

2016 // 17 SEASON Northrop and Walker Art Center Present CCN-BALLET DE LORRAINE Thu, Feb 16, 7:30 pm Carlson Family Stage Devoted Fabrications Sounddance Dear Friends of Northrop, Northrop at the University of Minnesota and Walker Art Center Present Tonight, we collaborate with Walker Art Center as part of their major survey: Merce Cunningham: Common Time, offering two of Cunningham’s groundbreaking choreographic works. The program begins with Devoted, a commissioned work by the trend setting choreographic duo Cecilia Bengolea and François Chaignaud. Infused with current dance hall and pop culture, CCN-BALLET DE these French choreographers are clearly influenced by modern and even post-modern American dance history—history that was forever changed by Cunningham's impact. LORRAINE Fabrications, the second work on our program, actually had its world premiere right here at Northrop in 1987, with Cunningham dancing, as he did in every performance by his company until he was 70. When he died a few months after his 90th birthday, he Choreographer and General Director had won every choreographic award and accolade imaginable, PETTER JACOBSSON Christine Tschida. Photo by Tim Rummelhoff. and left a legacy of nearly 200 works. It’s interesting to think about the audience who sat here at Northrop 30 years ago, and their world. Choreographer and Coordinator of Research Ronald Reagan was in his second term in the White House and had just struggled through a government THOMAS CALEY shutdown. News of the Iran-Contra Scandal had recently broken. Mad Cow Disease was discovered in the U.K., and the Minnesota Twins would go on to win their first World Series later that year. -

Giving Ideas Momentum and Scale Since 1731

2015 - 2019 IMPACT REPORT and scale since 1731 Giving ideas momentum Foreword – RDS President 2 Introduction - Chair of Foundation Board 3 Evolution of RDS Foundation 4 About the RDS Foundation 6 RDS Foundation in Numbers 8 Arts Programme 10 Agriculture & Rural Aff airs Programme 14 Science & Technology Programme 18 Enterprise Programme 22 Equestrian Programme 26 Library & Archives 30 Stakeholders 34 Funding 36 Funding Partners 38 Learning and Development 42 Conclusion 44 Since its inception in 1731, the RDS has grown from a small gathering of visionaries into one of the world’s oldest philanthropic organisations with the mission of seeing Ireland thrive culturally and economically. RDS Impact Report Foreword Introduction The purpose of the RDS is to see It is such an exciting time to be part Ireland thrive culturally and of the RDS story, an organisation economically and, in achieving this that has been bringing scale and over many generations, the Society momentum to ideas for nearly has made a significant contribution 300 years. across a number of different sectors. This report shows ways in which we are doing this today; This Impact Report is the first such report that captures the learning, how we are building upon our rich legacy, and, specifically, benefit and added value of the RDS programmes over the last five how our mission has found voice over the past five years. It years. It reflects on the journey the RDS has taken to reach this is filled with positive impact, of young minds nurtured and point across our five core programme areas; arts, agriculture, ideas turned into action.