Summary of 2007 Submission to NZ Press Council

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Ngati Awa Raupatu Report

THE NGATI AWA RAUPATU REPORT THE NGAT I AWA RAUPATU REPORT WA I 46 WAITANGI TRIBUNAL REPORT 1999 The cover design by Cliä Whiting invokes the signing of the Treaty of Waitangi and the consequent interwoven development of Maori and Pakeha history in New Zealand as it continuously unfolds in a pattern not yet completely known A Waitangi Tribunal report isbn 1-86956-252-6 © Waitangi Tribunal 1999 Edited and produced by the Waitangi Tribunal Published by Legislation Direct, Wellington, New Zealand Printed by PrintLink, Wellington, New Zealand Text set in Adobe Minion Multiple Master Captions set in Adobe Cronos Multiple Master LIST OF CONTENTS Letter of transmittal. ix Chapter 1Chapter 1: ScopeScopeScope. 1 1.1 Introduction. 1 1.2 The raupatu claims . 2 1.3 Tribal overlaps . 3 1.4 Summary of main åndings . 4 1.5 Claims not covered in this report . 10 1.6 Hearings. 10 Chapter 2: Introduction to the Tribes. 13 2.1 Ngati Awa and Tuwharetoa . 13 2.2 Origins of Ngati Awa . 14 2.3 Ngati Awa today . 16 2.4 Origins of Tuwharetoa. 19 2.5 Tuwharetoa today . .20 2.6 Ngati Makino . 22 Chapter 3: Background . 23 3.1 Musket wars. 23 3.2 Traders . 24 3.3 Missionaries . 24 3.4 The signing of the Treaty of Waitangi . 25 3.5 Law . 26 3.6 Principles of the Treaty of Waitangi. 28 Chapter 4: The Central North Island Wars . 33 4.1 The relevance of the wars to Ngati Awa. 33 4.2 Conclusion . 39 Chapter 5: The Völkner And Fulloon Slayings . -

Monday June 11

The Press, Christchurch June 5, 2012 15 MONDAY JUNE 11 Burkeand Hare Eagle Eye Tony Awards NZ Sheep Dog Trials 1 1 8.30pm, Rialto ★★★ ⁄2 8.30pm, TV3 ★★★ ⁄2 8.30pm, Arts Channel 9pm, Country99TV Despite being directed by an Shia LaBeouf and Michelle Same-day coverage of the 66th Remember when this kind of American (John Landis), this 2010 Monaghan star in this 2008 edition of America’s premiere thing used to be Sunday night film is very much a British thriller about two strangers who stage awards, hosted by Neil family viewing? Here’s a chance horror. Although laden with are thrown together by a Patrick Harris. Nominees this to relive those days and introduce lashings of blood and copious mysterious phone call from a year include a musical version of the next generation to the delights dismembered limbs, the horror is woman they have never met. the film Once and John Lithgow, of dog trialling. Men and canine suggested rather than g(l)orified ‘‘Strip-mines at least three James Earl Jones, Frank companions take on the wiliest and undercut by a Monty Python- Hitchcock classics – North by Langella, Philip Seymour ovines organisers can muster. esque approach to the murdering. Northwest, The Wrong Man and Hoffman and James Corden all Country99TV (Sky channel 99) Simon Pegg and Andy Serkis star. The Man Who Knew Too Much,’’ vying for best performance by a serves rural communities. wrote Boston Globe’s Ty Burr. Eagle Eye: 8.30pm, TV3. leading actor in a play. JAMES CROOT TV ONETV2 TV3 FOUR PRIME UKTV SKY SPORT 1 6am Breakfast Rawdon Christie, -

CHAPTER TWO Te Kooti Arikirangi Te Turuki

Te Kooti’s slow-cooking earth oven prophecy: A Patuheuheu account and a new transformative leadership theory Byron Rangiwai PhD ii Dedication This book is dedicated to my late maternal grandparents Rēpora Marion Brown and Edward Tapuirikawa Brown Arohanui tino nui iii Table of contents DEDICATION ..................................................................................................................... iii CHAPTER ONE: Introduction ............................................................................................ 1 CHAPTER TWO: Te Kooti Arikirangi Te Turuki .......................................................... 18 CHAPTER THREE: The Significance of Land and Land Loss ..................................... 53 CHAPTER FOUR: The emergence of Te Umutaoroa and a new transformative leadership theory ................................................................................................. 74 CHAPTER FIVE: Conclusion: Reflections on the Book ................................................. 83 BIBLIOGRAPHY ................................................................................................................ 86 Abbreviations AJHR: Appendices to the Journals of the House of Representatives MS: Manuscript MSS: Manuscripts iv CHAPTER ONE Introduction Ko Hikurangi te maunga Hikurangi is the mountain Ko Rangitaiki te awa Rangitaiki is the river Ko Koura te tangata Koura is the ancestor Ko Te Patuheuheu te hapū Te Patuheuheu is the clan Personal introduction The French philosopher Michel Foucault stated: “I don't -

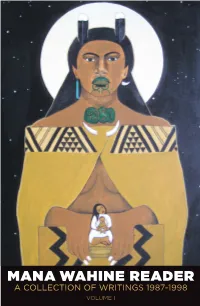

MANA WAHINE READER a COLLECTION of WRITINGS 1987-1998 2 VOLUME I Mana Wahine Reader a Collection of Writings 1987-1998 Volume I

MANA WAHINE READER A COLLECTION OF WRITINGS 1987-1998 2 VOLUME I Mana Wahine Reader A Collection of Writings 1987-1998 Volume I I First Published 2019 by Te Kotahi Research Institute Hamilton, Aotearoa/ New Zealand ISBN: 978-0-9941217-6-9 Education Research Monograph 3 © Te Kotahi Research Institute, 2019 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, without prior written permission of the publisher. Design Te Kotahi Research Institute Cover illustration by Robyn Kahukiwa Print Waikato Print – Gravitas Media The Mana Wahine Publication was supported by: Disclaimer: The editors and publisher gratefully acknowledge the permission granted to reproduce the material within this reader. Every attempt has been made to ensure that the information in this book is correct and that articles are as provided in their original publications. To check any details please refer to the original publication. II Mana Wahine Reader | A Collection of Writings 1987-1998, Volume I Mana Wahine Reader A Collection of Writings 1987-1998 Volume I Edited by: Leonie Pihama, Linda Tuhiwai Smith, Naomi Simmonds, Joeliee Seed-Pihama and Kirsten Gabel III Table of contents Poem Don’t Mess with the Māori Woman - Linda Tuhiwai Smith 01 Article 01 To Us the Dreamers are Important - Rangimarie Mihomiho Rose Pere 04 Article 02 He Aha Te Mea Nui? - Waerete Norman 13 Article 03 He Whiriwhiri Wahine: Framing Women’s Studies for Aotearoa Ngahuia Te Awekotuku 19 Article 04 Kia Mau, Kia Manawanui -

New Zealand Media Ownership 2018

NEW ZEALAND MEDIA OWNERSHIP 2020 AUT research centre for Journalism, Media and Democracy (JMAD) Edited by Merja Myllylahti and Wayne Hope December 7, 2020 ABOUT THIS REPORT This report is part of JMAD’s ongoing series of reports on New Zealand media ownership. Since 2011, the AUT research centre for Journalism, Media and Democracy (JMAD) has published reports that document and analyse developments within New Zealand media. These incorporate media ownership, market structures and key events during each year. The reports are freely available and accessible to anyone via the JMAD research centre: https://www.aut.ac.nz/study/study-options/communication- studies/research/journalism,-media-and-democracy-research-centre 2020 report team To celebrate the JMAD research centre’s 10th anniversary, this 10th New Zealand media ownership report is co-written by AUT lecturers who are experts in their fields. The report is co-edited by the JMAD Co-Directors Dr Merja Myllylahti and Professor Wayne Hope. Contributors Dr Sarah Baker Dr Peter Hoar Professor Wayne Hope Dr Rufus McEwan Dr Atakohu Middleton Dr Merja Myllylahti Dr Greg Treadwell This report is covered by the Creative Commons Attribution License 4.0 International. When reproducing any part of this report – including tables and graphs – full attribution must be given to the report author(s). 1 10TH ANNIVERSARY OF JOURNALISM, MEDIA AND DEMOCRACY RESEARCH CENTRE The AUT research centre for Journalism, Media and Democracy (JMAD) was established in 2010 by (then) Associate Professors Wayne Hope and Martin Hirst to promote research into the media and communication industries and to increase knowledge about news and professional practices in journalism. -

Acompendium of References

Te Matahauariki Institute Occasional Paper Series Number 8 2003 TE MATAPUNENGA: A COMPENDIUM OF REFERENCES TO CONCEPTS OF MAORI CUSTOMARY LAW Tui Adams Ass. Prof. Richard Benton Dr Alex Frame Paul Meredith Nena Benton Tonga Karena Published by Te Mātāhauariki Institute The University of Waikato Private Bag 3105 Hamilton, New Zealand http://www.lianz.waikato.ac.nz Telephone 64-7- 858 5033 Facsimile 64-7-858 5032 For further information or additional copies of the Occasional Papers please contact the publisher. This publication is copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private study, research, criticism, or review, as permitted under the Copyright Act, no part may be reproduced by any process without permission from the publishers. © Te Mātāhauariki Institute 2003 http://www.lianz.waikato.ac.nz ISSN 1175-7256 ISBN 0-9582343-3-7 TABLE OF CONTENTS TE MATAPUNENGA: PAPERS PRESENTED TO THE 20TH ANNUAL CONFERENCE OF THE AUSTRALIAN AND NEW ZEALAND LAW AND HISTORY SOCIETY 2001 THE IMPORTANCE OF WORDS: AN INTRODUCTION ……………………………………3 ASSOCIATE PROF. RICHARD A. BENTON SOURCING TE MATAPUNENGA: PRESENTATION NOTES ………………………………21 PAUL MEREDITH TE PÜ WÄNANGA: SOME NOTES FROM THE SEMINARS AND CONSULTATIONS WITH MÄORI EXPERTS ………………………………………………………………………27 NENA B.E. BENTON KAI-HAU – WORKING ON AN ENTRY FOR TE MATAPUNENGA ………………………41 DR ALEX FRAME LL.D TE TIKANGA ME TE WAIRUA: PLACING VALUE IN THE VALUES THAT UNDERPIN MAORI CUSTOM ………………………………………………………………………………45 TUI ADAMS QSO PAPER PRESENTED TO THE THE NEW ZEALAND HISTORICAL ASSOCIATION CONFERENCE 2001: FROM LOCAL TO GLOBAL (CHRISTCHURCH, 1-3 DECEMBER 2001) PERFORMING LAW: HAKARI AND MURU ………………………………………………...47 DR ALEX FRAME & PAUL MEREDITH PAPER PRESENTED FOR THE 7TH JOINT CONFERENCE “PRESERVATION OF ANCIENT CULTURES AND THE GLOBALIZATION SCENARIO” 22-24 NOVEMBER 2002 TE MATAPUNENGA: HOW DOES IT “META”? ENCOUNTERING WIDER EPISTEMOLOGICAL ISSUES: ………………………………………………………………...67 TONGA KARENA. -

Indigenous Cultural Values and Journalism in the Asia-Pacific Region: a Brief History of Māori Journalism

Indigenous cultural values and journalism in the Asia-Pacific region: A brief history of Māori journalism Accepted for publication in Asian Journal of Communication Folker Hanusch, Queensland University of Technology [email protected] Abstract A number of scholars in the Asia-Pacific region have in recent years pointed to the importance that cultural values play in influencing journalistic practices. The Asian values debate was followed up with empirical studies showing actual differences in news content when comparing Asian and Western journalism. At the same time, such studies have focused on national cultures only. This paper instead examines the issue against the background of an Indigenous culture in the Asia-Pacific region. It explores the way in which cultural values may have played a role in the journalistic practice of Māori journalists in Aotearoa New Zealand over the past nearly 200 years and finds numerous examples that demonstrate the significance of taking cultural values into account. The paper argues that the role played by cultural values is important to examine further, particularly in relation to journalistic practices amongst sub-national news cultures across the Asia-Pacific region. Keywords: cultural values, culture, indigenous, journalism, Maori, media, New Zealand Introduction The study of cultural values in communication has in recent years found particular attention in the context of journalism, public relations and advertising in the Asia-Pacific region. In relation to journalism, a number of scholars have demonstrated the way in which such values may be manifested differently when comparing Asian countries with those in North America and Western Europe (Servaes, 2000). -

Toward a Patuheuheu Hapū Development Model

Ko au ko Te Umutaoroa, ko Te Umutaoroa ko au: Toward a Patuheuheu Hapū Development Model Byron William Rangiwai A thesis submitted to Auckland University of Technology in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) February 2015 Dedication This work is dedicated to my maternal great-grandparents Koro Hāpurona Maki Nātana (1921-1994) and Nanny Pare Koekoeā Rikiriki (1918 - 1990). Koro and Nan you will always be missed. I ask you to continue to watch over the whānau and inspire us to maintain our Patuheuheutanga. Arohanui, your mokopuna tuarua. ii Table of contents Dedication ............................................................................................................................... ii Figures.... ................................................................................................................................ v Images…. ................................................................................................................................ v Maps........ ............................................................................................................................... vi Abbreviations ........................................................................................................................ vi Attestation of authorship .................................................................................................... vii Acknowledgments ............................................................................................................. -

Urban Maori Authorities (Draft)

JULIE MIDDLETON Ka Rangona te Reo: The Development of Māori-language Television Broadcasting in Aotearoa New Zealand Introduction New Zealanders today can hear Māori language broadcast in a variety of contexts: on Māori Television and to a lesser extent on state-owned TV1, TV2 and privately-held TV3, on digital platforms and via broadcasters‟ programmes-on-demand internet sites. However, these opportunities are a relatively recent development spurred by years of agitation by Māori about the decline of te reo Māori in an English-saturated world and the recognition that the powerful medium of television broadcasting could help promote, protect and enhance reo and tikanga. Māori-language television broadcasting is largely Government-funded, a support forced on the state as Māori successfully claimed their rights to representation under the Treaty of Waitangi. This literature review starts by canvassing the genesis of television in New Zealand and the limited contexts it provided for te reo Māori. It then describes grassroots political activism by Māori seeking a space for tikanga and reo Māori, and successful claims against the Government. We then trace the legislation that gave te reo Māori a place on the small screen and led to the birth of the country‟s first indigenous channel. Finally, this review briefly explores the expansion of reo Māori programming and platforms as Aotearoa New Zealand faces a very different broadcasting landscape. This literature review will not cover the development of Māori-language radio broadcasting, though many of the developments, especially those spurred by protest and subsequent legal action, are linked. For overviews on the growth of radio in te reo, see authors such as Patrick Day, Karen Neill, Julie Middleton is a journalist with twenty years’ experience working in New Zealand, the United Kingdom, and the Pacific, and is currently a writer, editor, and freelance media consultant. -

Kia Hiwa Rā! the Influence of Tikanga and the Language Revitalisation Agenda on the Practices and Perspectives of Māori Journalists Working in Reo-Māori News

Kia hiwa rā! The influence of tikanga and the language revitalisation agenda on the practices and perspectives of Māori journalists working in reo-Māori news Atakohu Julie Maree Middleton A thesis submitted to Auckland University of Technology in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) April 2020 School of Communication Studies Abstract Many aspects of Māori society, both public and private, are structured and influenced by tikanga, a system of values, beliefs, rituals, obligations and cultural practices developed and reinforced through intergenerational transmission and social validation (Mead, 2003). Tikanga – which we can describe as Māori ways of seeing, being and doing – shapes the outlook of Māori working as news and current affairs journalists in te reo Māori, who, like indigenous journalists in colonised countries elsewhere, have adapted the Anglo-American journalism tradition to reflect indigenous perspectives (Grixti, 2011; Hanusch, 2014). However, there is limited evidence on the ways in which tikanga manifests in journalistic practice and output. In addition, Māori journalism is funded as a vehicle for language revitalisation under a national strategy to rejuvenate and protect te reo. This strategy views reo-Māori news as an important component of the languagescape, and requires journalists to broadcast stories that are 70-100% in te reo. This presents a challenge for reporters when just 10.6% of the Māori population, or some 50,000 people, speak te reo “very well or “well”, but many more are learning (Statistics New Zealand, 2014, p. 8). This study, which combines video ethnography with semi-structured qualitative interviews and document analysis, examines the interplay of newswork, tikanga and the language revitalisation agenda to explicate what Māori journalism is. -

Release Date: 03 August 2021 TVNZ 1 & TVNZ 2 Schedule 01 August

Release Date: 03 August 2021 TVNZ 1 & TVNZ 2 Schedule 01 August 2021 - 29 January 2022 August: Week 32 w/c 01/08/2021 Sunday Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday Saturday 01/08/2021 02/08/2021 03/08/2021 04/08/2021 05/08/2021 06/08/2021 07/08/2021 06:00 Non Non Breakfast Early Preschool Breakfast Early Preschool Breakfast Early Preschool Breakfast Early Preschool Breakfast Early Preschool Te Karere Preschool 06:00 Commercial Commercial Commercial Commercial Commercial Commercial Commercial Commercial Free Free Free Free Free Free $1,150 $1,150 $1,150 $1,150 $1,150 $250 06:30 Breakfast 1 Breakfast 1 Breakfast 1 Breakfast 1 Breakfast 1 Hyundai 06:30 Country Calendar $1,950 - $1,950 - $1,950 - $1,950 - $1,950 - $450 - 07:00 Breakfast 2 The Dog and Breakfast 2 The Dog and Breakfast 2 The Dog and Breakfast 2 The Dog and Breakfast 2 The Dog and Fishing And 07:00 Pony Show Pony Show Pony Show Pony Show Pony Show Adventure $350 $350 $350 $350 $350 $450 07:30 Miraculous Miraculous Miraculous Miraculous Miraculous Infomercial Dragon Ball 07:30 Super $2,800 $350 $2,800 $350 $2,800 $350 $2,800 $350 $2,800 $350 $250 $450 08:00 Breakfast 3 Preschool Breakfast 3 Preschool Breakfast 3 Preschool Breakfast 3 Preschool Breakfast 3 Preschool Infomercial Lego Monkie 08:00 Commercial Commercial Commercial Commercial Commercial Kid TV Special Free Free Free Free Free - - - - - $250 $450 08:30 Faith In Action 08:30 $2,200 $2,200 $2,200 $2,200 $2,200 $250 09:00 Winning Infomercial Winning Infomercial Winning Infomercial Winning Infomercial Winning Infomercial -

Maori Mental Health & Addiction Wellbeing Framework

Midland Mental Health & Addiction Taiahaha Taiahaha - Māori Mental Health & Addiction Wellbeing Framework Prepared by Akatu Marsters April 2020 0 FINAL Karakia Nau mai ra e Let the call of the bellbird Kaha mai te wairua e Guide you, strengthening your spirit Ko te karanga o ngā Kōpara as we reach out to uphold and Ka whai atu e encourage you, welcoming you Kei roto ngā ringā I hāpaitia ra E te whānau e Nau mai ra He tāngata e Kia mau te aroha If we pluck the root of the flax I ngā wa katoa where will the bellbird sing? Koenei te mahara an ageless reminder Ki a mau tonu e hold on to dignity of life (aro ha) Hutia te rito O te harakeke Ke hei te ko mako e kō? E kī mai He tāngata e Acknowledgements Firstly, we would like to acknowledge Hine Moeke-Murray and the late Tau Moeke for the composition of the Midland Mental Health and Addiction (MH&A) waiata which has been published in this document as the “Karakia”. The Midland regional networks are forever grateful for the support and guidance provided by Tau over the years and we hope that through this “karakia” his memory will forever be connected to our region. We are grateful to Nick Tupara for gifting us Taiahaha Taiahaha, a “Call to Action”. The use of the phrase tai...a....ha...ha is the tide of breath, the breath of IO, the breath of papa, the breath of wellbeing. This illustration reflects what whānau who participated in all the Midland wānanga view as “wellbeing”.