Urban Maori Authorities (Draft)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Ngati Awa Raupatu Report

THE NGATI AWA RAUPATU REPORT THE NGAT I AWA RAUPATU REPORT WA I 46 WAITANGI TRIBUNAL REPORT 1999 The cover design by Cliä Whiting invokes the signing of the Treaty of Waitangi and the consequent interwoven development of Maori and Pakeha history in New Zealand as it continuously unfolds in a pattern not yet completely known A Waitangi Tribunal report isbn 1-86956-252-6 © Waitangi Tribunal 1999 Edited and produced by the Waitangi Tribunal Published by Legislation Direct, Wellington, New Zealand Printed by PrintLink, Wellington, New Zealand Text set in Adobe Minion Multiple Master Captions set in Adobe Cronos Multiple Master LIST OF CONTENTS Letter of transmittal. ix Chapter 1Chapter 1: ScopeScopeScope. 1 1.1 Introduction. 1 1.2 The raupatu claims . 2 1.3 Tribal overlaps . 3 1.4 Summary of main åndings . 4 1.5 Claims not covered in this report . 10 1.6 Hearings. 10 Chapter 2: Introduction to the Tribes. 13 2.1 Ngati Awa and Tuwharetoa . 13 2.2 Origins of Ngati Awa . 14 2.3 Ngati Awa today . 16 2.4 Origins of Tuwharetoa. 19 2.5 Tuwharetoa today . .20 2.6 Ngati Makino . 22 Chapter 3: Background . 23 3.1 Musket wars. 23 3.2 Traders . 24 3.3 Missionaries . 24 3.4 The signing of the Treaty of Waitangi . 25 3.5 Law . 26 3.6 Principles of the Treaty of Waitangi. 28 Chapter 4: The Central North Island Wars . 33 4.1 The relevance of the wars to Ngati Awa. 33 4.2 Conclusion . 39 Chapter 5: The Völkner And Fulloon Slayings . -

Monday June 11

The Press, Christchurch June 5, 2012 15 MONDAY JUNE 11 Burkeand Hare Eagle Eye Tony Awards NZ Sheep Dog Trials 1 1 8.30pm, Rialto ★★★ ⁄2 8.30pm, TV3 ★★★ ⁄2 8.30pm, Arts Channel 9pm, Country99TV Despite being directed by an Shia LaBeouf and Michelle Same-day coverage of the 66th Remember when this kind of American (John Landis), this 2010 Monaghan star in this 2008 edition of America’s premiere thing used to be Sunday night film is very much a British thriller about two strangers who stage awards, hosted by Neil family viewing? Here’s a chance horror. Although laden with are thrown together by a Patrick Harris. Nominees this to relive those days and introduce lashings of blood and copious mysterious phone call from a year include a musical version of the next generation to the delights dismembered limbs, the horror is woman they have never met. the film Once and John Lithgow, of dog trialling. Men and canine suggested rather than g(l)orified ‘‘Strip-mines at least three James Earl Jones, Frank companions take on the wiliest and undercut by a Monty Python- Hitchcock classics – North by Langella, Philip Seymour ovines organisers can muster. esque approach to the murdering. Northwest, The Wrong Man and Hoffman and James Corden all Country99TV (Sky channel 99) Simon Pegg and Andy Serkis star. The Man Who Knew Too Much,’’ vying for best performance by a serves rural communities. wrote Boston Globe’s Ty Burr. Eagle Eye: 8.30pm, TV3. leading actor in a play. JAMES CROOT TV ONETV2 TV3 FOUR PRIME UKTV SKY SPORT 1 6am Breakfast Rawdon Christie, -

A Comparative Study of the Digital Switchover Process in Nigeria and New Zealand

A COMPARATIVE STUDY OF THE DIGITAL SWITCHOVER PROCESS IN NIGERIA AND NEW ZEALAND. BY ABIKANLU, OLORUNFEMI ENI. A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN MEDIA AND COMMUNICATION. UNIVERSITY OF CANTERBURY 2018 DEDICATION I dedicate this thesis to the God that makes all things possible. Also, to my awesome and loving Wife and Daughter, Marissa and Enïola. i | P a g e ACKNOWLEDGEMENT I heartily acknowledge the support, unrelentless commitment and dedication of my supervisors, Dr. Zita Joyce and Dr. Babak Bahador who both ensured that these thesis meets an international level of academic research. I value their advice and contributions to the thesis and without their highly critical reviews and feedback, the thesis will be nothing than a complete recycle of existing knowledge. I also appreciate the valuable contributions of my Examiners, Professor Jock Given of the Swinburne University of Technology, Australia and Assistant Professor Gregory Taylor of the University of Calgary, Canada. The feedback and report of the Examination provided the much needed critical evaluation of my research to improve my research findings. I also appreciate Associate Professor Donald Matheson for chairing my oral examination. I also appreciate the University of Canterbury for providing me with various opportunities to acquire valuable skills in my course of research, academic learning support, teaching and administrative works. Particularly, I appreciate Professor Linda Jean Kenix, who gave me an opportunity as a research assistant during the course of my research. I value this rare opportunity as it was my first major exposure to academic research and an opportunity to understand the academia beyond my research topic. -

CHAPTER TWO Te Kooti Arikirangi Te Turuki

Te Kooti’s slow-cooking earth oven prophecy: A Patuheuheu account and a new transformative leadership theory Byron Rangiwai PhD ii Dedication This book is dedicated to my late maternal grandparents Rēpora Marion Brown and Edward Tapuirikawa Brown Arohanui tino nui iii Table of contents DEDICATION ..................................................................................................................... iii CHAPTER ONE: Introduction ............................................................................................ 1 CHAPTER TWO: Te Kooti Arikirangi Te Turuki .......................................................... 18 CHAPTER THREE: The Significance of Land and Land Loss ..................................... 53 CHAPTER FOUR: The emergence of Te Umutaoroa and a new transformative leadership theory ................................................................................................. 74 CHAPTER FIVE: Conclusion: Reflections on the Book ................................................. 83 BIBLIOGRAPHY ................................................................................................................ 86 Abbreviations AJHR: Appendices to the Journals of the House of Representatives MS: Manuscript MSS: Manuscripts iv CHAPTER ONE Introduction Ko Hikurangi te maunga Hikurangi is the mountain Ko Rangitaiki te awa Rangitaiki is the river Ko Koura te tangata Koura is the ancestor Ko Te Patuheuheu te hapū Te Patuheuheu is the clan Personal introduction The French philosopher Michel Foucault stated: “I don't -

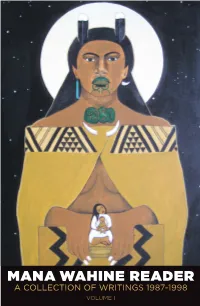

MANA WAHINE READER a COLLECTION of WRITINGS 1987-1998 2 VOLUME I Mana Wahine Reader a Collection of Writings 1987-1998 Volume I

MANA WAHINE READER A COLLECTION OF WRITINGS 1987-1998 2 VOLUME I Mana Wahine Reader A Collection of Writings 1987-1998 Volume I I First Published 2019 by Te Kotahi Research Institute Hamilton, Aotearoa/ New Zealand ISBN: 978-0-9941217-6-9 Education Research Monograph 3 © Te Kotahi Research Institute, 2019 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, without prior written permission of the publisher. Design Te Kotahi Research Institute Cover illustration by Robyn Kahukiwa Print Waikato Print – Gravitas Media The Mana Wahine Publication was supported by: Disclaimer: The editors and publisher gratefully acknowledge the permission granted to reproduce the material within this reader. Every attempt has been made to ensure that the information in this book is correct and that articles are as provided in their original publications. To check any details please refer to the original publication. II Mana Wahine Reader | A Collection of Writings 1987-1998, Volume I Mana Wahine Reader A Collection of Writings 1987-1998 Volume I Edited by: Leonie Pihama, Linda Tuhiwai Smith, Naomi Simmonds, Joeliee Seed-Pihama and Kirsten Gabel III Table of contents Poem Don’t Mess with the Māori Woman - Linda Tuhiwai Smith 01 Article 01 To Us the Dreamers are Important - Rangimarie Mihomiho Rose Pere 04 Article 02 He Aha Te Mea Nui? - Waerete Norman 13 Article 03 He Whiriwhiri Wahine: Framing Women’s Studies for Aotearoa Ngahuia Te Awekotuku 19 Article 04 Kia Mau, Kia Manawanui -

New Zealand Media Ownership 2018

NEW ZEALAND MEDIA OWNERSHIP 2020 AUT research centre for Journalism, Media and Democracy (JMAD) Edited by Merja Myllylahti and Wayne Hope December 7, 2020 ABOUT THIS REPORT This report is part of JMAD’s ongoing series of reports on New Zealand media ownership. Since 2011, the AUT research centre for Journalism, Media and Democracy (JMAD) has published reports that document and analyse developments within New Zealand media. These incorporate media ownership, market structures and key events during each year. The reports are freely available and accessible to anyone via the JMAD research centre: https://www.aut.ac.nz/study/study-options/communication- studies/research/journalism,-media-and-democracy-research-centre 2020 report team To celebrate the JMAD research centre’s 10th anniversary, this 10th New Zealand media ownership report is co-written by AUT lecturers who are experts in their fields. The report is co-edited by the JMAD Co-Directors Dr Merja Myllylahti and Professor Wayne Hope. Contributors Dr Sarah Baker Dr Peter Hoar Professor Wayne Hope Dr Rufus McEwan Dr Atakohu Middleton Dr Merja Myllylahti Dr Greg Treadwell This report is covered by the Creative Commons Attribution License 4.0 International. When reproducing any part of this report – including tables and graphs – full attribution must be given to the report author(s). 1 10TH ANNIVERSARY OF JOURNALISM, MEDIA AND DEMOCRACY RESEARCH CENTRE The AUT research centre for Journalism, Media and Democracy (JMAD) was established in 2010 by (then) Associate Professors Wayne Hope and Martin Hirst to promote research into the media and communication industries and to increase knowledge about news and professional practices in journalism. -

Acompendium of References

Te Matahauariki Institute Occasional Paper Series Number 8 2003 TE MATAPUNENGA: A COMPENDIUM OF REFERENCES TO CONCEPTS OF MAORI CUSTOMARY LAW Tui Adams Ass. Prof. Richard Benton Dr Alex Frame Paul Meredith Nena Benton Tonga Karena Published by Te Mātāhauariki Institute The University of Waikato Private Bag 3105 Hamilton, New Zealand http://www.lianz.waikato.ac.nz Telephone 64-7- 858 5033 Facsimile 64-7-858 5032 For further information or additional copies of the Occasional Papers please contact the publisher. This publication is copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private study, research, criticism, or review, as permitted under the Copyright Act, no part may be reproduced by any process without permission from the publishers. © Te Mātāhauariki Institute 2003 http://www.lianz.waikato.ac.nz ISSN 1175-7256 ISBN 0-9582343-3-7 TABLE OF CONTENTS TE MATAPUNENGA: PAPERS PRESENTED TO THE 20TH ANNUAL CONFERENCE OF THE AUSTRALIAN AND NEW ZEALAND LAW AND HISTORY SOCIETY 2001 THE IMPORTANCE OF WORDS: AN INTRODUCTION ……………………………………3 ASSOCIATE PROF. RICHARD A. BENTON SOURCING TE MATAPUNENGA: PRESENTATION NOTES ………………………………21 PAUL MEREDITH TE PÜ WÄNANGA: SOME NOTES FROM THE SEMINARS AND CONSULTATIONS WITH MÄORI EXPERTS ………………………………………………………………………27 NENA B.E. BENTON KAI-HAU – WORKING ON AN ENTRY FOR TE MATAPUNENGA ………………………41 DR ALEX FRAME LL.D TE TIKANGA ME TE WAIRUA: PLACING VALUE IN THE VALUES THAT UNDERPIN MAORI CUSTOM ………………………………………………………………………………45 TUI ADAMS QSO PAPER PRESENTED TO THE THE NEW ZEALAND HISTORICAL ASSOCIATION CONFERENCE 2001: FROM LOCAL TO GLOBAL (CHRISTCHURCH, 1-3 DECEMBER 2001) PERFORMING LAW: HAKARI AND MURU ………………………………………………...47 DR ALEX FRAME & PAUL MEREDITH PAPER PRESENTED FOR THE 7TH JOINT CONFERENCE “PRESERVATION OF ANCIENT CULTURES AND THE GLOBALIZATION SCENARIO” 22-24 NOVEMBER 2002 TE MATAPUNENGA: HOW DOES IT “META”? ENCOUNTERING WIDER EPISTEMOLOGICAL ISSUES: ………………………………………………………………...67 TONGA KARENA. -

Television New Zealand Limited Statement of Intent for 3 Years En Ding 30 June 2014

Television New Zealand Limited Statement of Intent For 3 Years En ding 30 June 2014 Table of Contents 1. Introduction…………………………………………………………………… ... 1 2. Who we are and what we do………………………………………………… .. 1 3. The operating environment…………………………………………………… .. 6 4. What we plan to do: operations and activities……………………………… .. 8 5. Capability……………………………………………………………………… .. 10 6. Non-Financial performance…………………………………………………… . 11 7. Financial performance………………………… ……………………………… .. 12 8. Dividends and capital expenditure…………………………………………… . 13 9. Reporting and consultation……………………………………………………… 13 10. Statement of Forecast Service Performance…………………………………… .14 APPENDIX I – Board of Directors – Governance and Committees APPENDIX II – Forecast financial statements APPENDIX III – Reporting requirements APPENDIX IV – Consultation, subsidiary and associated companies 26 July 2011 Hon Dr Jonathan Coleman Minister of Broadcasting Hon Bill English Minister of Finance Parliament Buildings WELLINGTON Dear Ministers In many respects FY2011 was a good year for TVNZ. The company reduced operating costs, increased advertising market share and had excellent on screen performances. TVNZ’s goal is to perform even better in FY2012. The global financial crisis still impacts the New Zealand economy and continues to be felt by advertising reliant media. We expect there will, however, be a gradual improvement in advertising revenues throughout FY2012. That means in FY2012 TVNZ will still have a focus on cost control, productivity improvements and efficient use of assets. The company will also keep pressure on competitors around advertising market share and continue to search for, and put to air, outstanding programmes. At a macro level, the acceleration of the structural changes in the New Zealand and international media business where digital content can be accessed almost at any time across multiple devices means TVNZ’s strategy of “inspiring New Zealanders on every screen” is locked in as the company’s mantra. -

Indigenous Cultural Values and Journalism in the Asia-Pacific Region: a Brief History of Māori Journalism

Indigenous cultural values and journalism in the Asia-Pacific region: A brief history of Māori journalism Accepted for publication in Asian Journal of Communication Folker Hanusch, Queensland University of Technology [email protected] Abstract A number of scholars in the Asia-Pacific region have in recent years pointed to the importance that cultural values play in influencing journalistic practices. The Asian values debate was followed up with empirical studies showing actual differences in news content when comparing Asian and Western journalism. At the same time, such studies have focused on national cultures only. This paper instead examines the issue against the background of an Indigenous culture in the Asia-Pacific region. It explores the way in which cultural values may have played a role in the journalistic practice of Māori journalists in Aotearoa New Zealand over the past nearly 200 years and finds numerous examples that demonstrate the significance of taking cultural values into account. The paper argues that the role played by cultural values is important to examine further, particularly in relation to journalistic practices amongst sub-national news cultures across the Asia-Pacific region. Keywords: cultural values, culture, indigenous, journalism, Maori, media, New Zealand Introduction The study of cultural values in communication has in recent years found particular attention in the context of journalism, public relations and advertising in the Asia-Pacific region. In relation to journalism, a number of scholars have demonstrated the way in which such values may be manifested differently when comparing Asian countries with those in North America and Western Europe (Servaes, 2000). -

Toward a Patuheuheu Hapū Development Model

Ko au ko Te Umutaoroa, ko Te Umutaoroa ko au: Toward a Patuheuheu Hapū Development Model Byron William Rangiwai A thesis submitted to Auckland University of Technology in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) February 2015 Dedication This work is dedicated to my maternal great-grandparents Koro Hāpurona Maki Nātana (1921-1994) and Nanny Pare Koekoeā Rikiriki (1918 - 1990). Koro and Nan you will always be missed. I ask you to continue to watch over the whānau and inspire us to maintain our Patuheuheutanga. Arohanui, your mokopuna tuarua. ii Table of contents Dedication ............................................................................................................................... ii Figures.... ................................................................................................................................ v Images…. ................................................................................................................................ v Maps........ ............................................................................................................................... vi Abbreviations ........................................................................................................................ vi Attestation of authorship .................................................................................................... vii Acknowledgments ............................................................................................................. -

Annual Report 2010

New Zealand Tourism Research Institute Annual Report 2010 1 IMPROVING THE SUSTAINABILITY AND PROFITABILITY OF TOURISM NZTRI I Private Bag 92006 I Auckland 1142 I New Zealand I Ph (+64 9) 921 9999 ext 8890 I [email protected] I www.nztri.org 2 CONTENTS Director’s Report 4 Research Programmes 5 Project Overview 17 Externally Funded Projects 2010 - Highlights 19 Training and Capacity Building 20 International Outreach 24 NZTRI/AUT Conferences 25 Community Outreach 26 public relations 28 Staffing 38 Publications 42 3 DIRECTOR’S REPORT The New Zealand Tourism Research Institute (NZTRI) is a multi-disciplinary and multi-institutional grouping of researchers, graduate students, and industry leaders, based at AUT. The Institute was established in 1999. The objectives of NZTRI are: • To develop timely and innovative research solutions for the tourism industry and those who depend on it. The focus is on helping to develop a profitable and sustainable industry which provides tangible benefits for business, residents and visitors. • To develop tools that can assist in maximising the links between tourism and local economies, and which can also mitigate the negative impacts associated with tourism. • To obtain funding from both the private and the public sectors which can support advanced graduate study in areas of vital importance to tourism development in New Zealand and globally. NZTRI operates across scales from the local and regional through to the national and global and has over 70 members and associate members. There are currently 22 PhD students studying in or about to join the Institute and a number of MPhil students. -

See It. Love It. Do

A16 Thursday, November 3, 2011 THE PRESS, Christchurch SITUATION © Copyright Meteorological Service of New Zealand Limited 2011 Thursday, November 3, 2011 MAIN CENTRE FORECASTS For the latest weather information including Weather Warnings A complex trough of low pressure with embedded fronts affects New Zealand for the next few days. A front moves to the east of New Zealand early Friday, and a AUCKLAND 11 21 HAMILTON 10 19 WELLINGTON 11 16 second cold front moves north-eastward over the country to lie across the central 2.0 Mainly fine; rain from evening. North-west wind. Mainly fine; rain from evening. North-westerlies. Fine at first then afternoon rain. Strong north-west. North Island late Friday. A cold south-west flow follows the front with snow to 1.0 QUEENSTOWN 6 12 DUNEDIN 7 15 INVERCARGILL 5 11 low levels in the far south. A west or south-west flow continues over the country Takaka Brief morning rain. Gusty west or southwesterlies. Morning rain then showers. Gusty westerlies. Rain at times. Strong westerlies. through to Monday, with further fronts crossing the far south. 2.5 8 16 REGIONAL FORECASTS Motueka CHRISTCHURCH’S FIVE-DAY FORECAST 9 17 Picton NELSON MARLBOROUGH WESTLAND 10 15 9 17 11 16 TODAY Rain at times in the west, and brief TODAY Mostly fine, apart from brief afternoon TODAY Rain easing to showers during the TODAY: Nelson Wellington Morning rain, then fine. Gusty north-west developing. 7 17 afternoon rain spreading east. rain about the Sounds and western morning. Westerly winds. Blenheim NIL Gusty westerlies, easing.