2 Between the Israelites and the Khazars: 1900–1918

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Image of the Cumans in Medieval Chronicles

Caroline Gurevich THE IMAGE OF THE CUMANS IN MEDIEVAL CHRONICLES: OLD RUSSIAN AND GEORGIAN SOURCES IN THE TWELFTH AND THIRTEENTH CENTURIES MA Thesis in Medieval Studies CEU eTD Collection Central European University Budapest May 2017 THE IMAGE OF THE CUMANS IN MEDIEVAL CHRONICLES: OLD RUSSIAN AND GEORGIAN SOURCES IN THE TWELFTH AND THIRTEENTH CENTURIES by Caroline Gurevich (Russia) Thesis submitted to the Department of Medieval Studies, Central European University, Budapest, in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the Master of Arts degree in Medieval Studies. Accepted in conformance with the standards of the CEU. ____________________________________________ Chair, Examination Committee ____________________________________________ Thesis Supervisor ____________________________________________ Examiner ____________________________________________ CEU eTD Collection Examiner Budapest May 2017 THE IMAGE OF THE CUMANS IN MEDIEVAL CHRONICLES: OLD RUSSIAN AND GEORGIAN SOURCES IN THE TWELFTH AND THIRTEENTH CENTURIES by Caroline Gurevich (Russia) Thesis submitted to the Department of Medieval Studies, Central European University, Budapest, in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the Master of Arts degree in Medieval Studies. Accepted in conformance with the standards of the CEU. ____________________________________________ External Reader CEU eTD Collection Budapest May 2017 THE IMAGE OF THE CUMANS IN MEDIEVAL CHRONICLES: OLD RUSSIAN AND GEORGIAN SOURCES IN THE TWELFTH AND THIRTEENTH CENTURIES by Caroline Gurevich (Russia) Thesis -

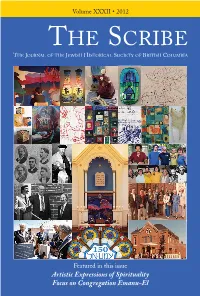

Focus on Congregation Emanu-El the SCRIBE

Volume XXXII • 2012 THE SCRIBE THE JOURNAL OF THE JEWISH HISTORICAL SOCIETY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA Featured in this issue Artistic Expressions of Spirituality Focus on Congregation Emanu-El THE SCRIBE THE JOURNAL OF THE JEWISH HISTORICAL SOCIETY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA Artistic Expressions of Spirituality Focus on Congregation Emanu-El Volume XXXII • 2012 This issue of The Scribe has been generously supported by: the Cyril Leonoff Fund for the Jewish Historical Society of British Columbia; the Yosef Wosk Publication Endowment Fund; Dora and Sid Golden and family; Betty and Irv Nitkin; and an anonymous donor. Editor: Cynthia Ramsay Publications Committee: Betty Nitkin, Perry Seidelman and archivist Jennifer Yuhasz, with appreciation to Josie Tonio McCarthy and Marcy Babins Layout: Western Sky Communications Ltd. Statements of fact or opinion appearing in The Scribe are made on the responsibility of the authors alone and do not imply the endorsements of the editor or the Jewish Historical Society of British Columbia. Please address all submissions and communications on editorial and circulation matters to: THE SCRIBE Jewish Historical Society of British Columbia 6184 Ash Street, Vancouver, B.C., V5Z 3G9 604-257-5199 • [email protected] • http://www.jewishmuseum.ca Membership Rates: Households – $54; Institutions/Organizations – $75 Includes one copy of each issue of The Scribe and The Chronicle Back issues and e xtra copies – $20 plus postage ISSN 0824 6048 © The Jewish Historical Society of British Columbia is a nonprofit organization. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored or transmitted without the written permission of the publisher, with the following exception: JHSBC grants permission to individuals to download or print single copies of articles for personal use. -

The Languages of the Jews: a Sociolinguistic History Bernard Spolsky Index More Information

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-05544-5 - The Languages of the Jews: A Sociolinguistic History Bernard Spolsky Index More information Index Abu El-Haj, Nadia, 178 Alliance Israélite Universelle, 128, 195, 197, Afrikaans, 15, 243 238, 239, 242, 256 learned by Jews, 229 Almohads, 115 Afrikaaners forced conversions, 115 attitude to Jews, 229 Granada, 139 Afro-Asiatic persecution, 115, 135, 138 language family, 23 alphabet Agudath Israel, 252 Hebrew, 30 Yiddish, 209 Alsace, 144 Ahaz, 26, 27 became French, 196 Akkadian, 20, 23, 24, 25, 26, 30, 36, 37, expulsion, 125 39, 52 Alsace and Lorraine borrowings, 60 Jews from East, 196 Aksum, 91 al-Yahūdiyya, 85 al-Andalus, 105, 132, 133 Amarna, 19 emigration, 135 American English Jews a minority, 133 Yiddish influence, 225 Jews’ languages, 133 Amharic, 5, 8, 9, 90, 92 languages, 136 Amoraim, 60 Aleppo, 102 Amsterdam emigration, 225 Jewish publishing, 169 Jewish Diasporas, 243 Jewish settlement, 198 Jewish settlement, 243 multilingualism, 31 Alexander the Great, 46 Anglo-Israelite beliefs, 93 Alexandria, 47, 59, 103 anti-language, 44 Hebrew continuity, 48 Antiochus, 47, 56 Jews, 103 Antipas, 119 Alfonso X, 137 Antwerp Algeria, 115 Anusim, 199 consistories, 236 multilingualism, 199 emigration, 197, 236, 237 Yiddish maintained, 199 French rule, 234 Antwerpian Brabantic, 18 French schools, 236 Anusim, 132, 139, 232 Jews acquire French, 236 Algeria, 115 Vichy policy, 236 Belgium, 199 342 © in this web service Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-05544-5 - -

Agroinvest Gender Analysis: Opportunities to Strengthen Family

AgroInvest Project GENDER ANALYSIS: OPPORTUNITIES TO STRENGTHEN FAMILY FARMS AND THE AGRICULTURE SECTOR IN UKRAINE August 2013 This publication was produced for review by the United States Agency for International Development. It was prepared by Chemonics International Inc. The author’s views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views of the United States Agency for International Development or the United States Government. GENDER ANALYSIS: OPPORTUNITIES TO STRENGTHEN FAMILY FARMS AND THE AGRICULTURE SECTOR IN UKRAINE Contract No.AID-121-C-1100001 CONTENTS Executive Summary ............................................................................................. 2 Acronyms……………………………………………………………………………….11 Acknowledgements……………………………………………………………………12 A. Introduction ..................................................................................................... 13 B. Background: The Gender Equality Context in Ukraine…………………….…..15 C. Gender Analysis Methodology........................................................................ 18 D. Portrait of Ukrainian Woman Farmers and the Family Farm .......................... 21 E. Analysis of Gender-related Constraints ......................................................... 37 F. Recommendations .......................................................................................... 45 Annexes: Annex A: Written Sources Reviewed ........................................................... 50 Annex B: List of Informants ......................................................................... -

LCSH Section J

J (Computer program language) J. I. Case tractors Thurmond Dam (S.C.) BT Object-oriented programming languages USE Case tractors BT Dams—South Carolina J (Locomotive) (Not Subd Geog) J.J. Glessner House (Chicago, Ill.) J. Strom Thurmond Lake (Ga. and S.C.) BT Locomotives USE Glessner House (Chicago, Ill.) UF Clark Hill Lake (Ga. and S.C.) [Former J & R Landfill (Ill.) J.J. "Jake" Pickle Federal Building (Austin, Tex.) heading] UF J and R Landfill (Ill.) UF "Jake" Pickle Federal Building (Austin, Tex.) Clark Hill Reservoir (Ga. and S.C.) J&R Landfill (Ill.) Pickle Federal Building (Austin, Tex.) Clarks Hill Reservoir (Ga. and S.C.) BT Sanitary landfills—Illinois BT Public buildings—Texas Strom Thurmond Lake (Ga. and S.C.) J. & W. Seligman and Company Building (New York, J. James Exon Federal Bureau of Investigation Building Thurmond Lake (Ga. and S.C.) N.Y.) (Omaha, Neb.) BT Lakes—Georgia USE Banca Commerciale Italiana Building (New UF Exon Federal Bureau of Investigation Building Lakes—South Carolina York, N.Y.) (Omaha, Neb.) Reservoirs—Georgia J 29 (Jet fighter plane) BT Public buildings—Nebraska Reservoirs—South Carolina USE Saab 29 (Jet fighter plane) J. Kenneth Robinson Postal Building (Winchester, Va.) J.T. Berry Site (Mass.) J.A. Ranch (Tex.) UF Robinson Postal Building (Winchester, Va.) UF Berry Site (Mass.) BT Ranches—Texas BT Post office buildings—Virginia BT Massachusetts—Antiquities J. Alfred Prufrock (Fictitious character) J.L. Dawkins Post Office Building (Fayetteville, N.C.) J.T. Nickel Family Nature and Wildlife Preserve (Okla.) USE Prufrock, J. Alfred (Fictitious character) UF Dawkins Post Office Building (Fayetteville, UF J.T. -

O. Karataev TITLE of the ANCIENT TURKS: “KAGAN” (QAGAN) and “ZHABGU” (YABGU)

ISSN 1563-0269, еISSN 2617-8893 Journal of history. №1 (96). 2020 https://bulletin-history.kaznu.kz IRSTI 03.29.00 https://doi.org/10.26577/JH.2020.v96.i1.02 O. Karataev Kastamonu University, Turkey, Kastamonu, е-mail: [email protected] TITLE OF THE ANCIENT TURKS: “KAGAN” (QAGAN) AND “ZHABGU” (YABGU) The Turks managed to create a huge empire. Territory – from the Altai mountains in the east to the Black Sea in the west, from the upper Yenisei in the north to the upper Amu Darya in the south. At the beginning of the VI century, the territory of Kazakhstan came under the authority of the Turkic Kaganate. Turkic Kaganate is the first state in Kazakhstan. Its basis was the union of Turkic-speaking tribes, which was headed by the kagan. The state, based on tribal traditions, was based on military-administrative management. It was part of a system of relations with such major states of the time as Iran and Byzan- tium. China was a tributary of the kaganate. The title in many cultures played the role of an important indicator of the international prestige of the state. As is known, only members of the Ashin clan had the sacred right to supreme power in the Turkic Kaganate. Possession of one or another title, occupation of one or another place in the political and state structure of society, depended on many circumstances, the main of which was belonging to a particular tribe in a tribal union, clan in a tribe, etc. Social deter- minants (titles, ranks, positions), as the most significant components of ancient Turkic anthroponomy, contained complete information about the social status of the bearer of a given name, its origin and membership in a particular layer of society, data on its place in the political structure of society and the administrative structure . -

Ordinary Jerusalem 1840–1940

Ordinary Jerusalem 1840–1940 Angelos Dalachanis and Vincent Lemire - 978-90-04-37574-1 Downloaded from Brill.com03/21/2019 10:36:34AM via free access Open Jerusalem Edited by Vincent Lemire (Paris-Est Marne-la-Vallée University) and Angelos Dalachanis (French School at Athens) VOLUME 1 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.com/opje Angelos Dalachanis and Vincent Lemire - 978-90-04-37574-1 Downloaded from Brill.com03/21/2019 10:36:34AM via free access Ordinary Jerusalem 1840–1940 Opening New Archives, Revisiting a Global City Edited by Angelos Dalachanis and Vincent Lemire LEIDEN | BOSTON Angelos Dalachanis and Vincent Lemire - 978-90-04-37574-1 Downloaded from Brill.com03/21/2019 10:36:34AM via free access This is an open access title distributed under the terms of the prevailing CC-BY-NC-ND License at the time of publication, which permits any non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided no alterations are made and the original author(s) and source are credited. The Open Jerusalem project has received funding from the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Seventh Framework Programme (FP7/2007-2013) (starting grant No 337895) Note for the cover image: Photograph of two women making Palestinian point lace seated outdoors on a balcony, with the Old City of Jerusalem in the background. American Colony School of Handicrafts, Jerusalem, Palestine, ca. 1930. G. Eric and Edith Matson Photograph Collection, Library of Congress. https://www.loc.gov/item/mamcol.054/ Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Dalachanis, Angelos, editor. -

Charlemagne and the Dialogue of Civilizations

www.amatterofmind.us From the desk of Pierre Beaudry Page 1 of 26 CHARLEMAGNE AND THE DIALOGUE OF CIVILIZATONS by Pierre Beaudry, March 24, 2015 INTRODUCTION “The present option for all deserving humanity, lies essentially, in creating a better future for all mankind, in the option for realizing the seemingly impossible necessity, which makes for the sweetest of the achieved dreams of mankind's achievements: for the sake of realizing that the future of all mankind, is the seemingly impossible.” Lyndon LaRouche, On the Subject of Germany’s Role. What prompted me to write on this strategic question at this time is the statement that General Douglas McArthur made at the end of World War II, when he accepted the surrender of the Japanese military forces on the deck of the battleship Missouri, on September 2, 1945. McArthur had fully realized that “we have had our last chance” and that the next war was going to be a war of extension, because he understood that a thermonuclear war was unsurvivable. He stated: "Military alliances, balances of power, leagues of nations, all in turn failed, leaving the only path to be by way of the crucible of war. The utter destructiveness of war now blots out this alternative. We have had our last chance (My emphasis). If we will not devise some greater and more equitable system, Armageddon will be at our door. The problem is basically theological and involves a spiritual recrudescence and improvement www.amatterofmind.us From the desk of Pierre Beaudry Page 2 of 26 of human character that will synchronize with our almost matchless advances in science, art, literature, and all material and cultural developments of the past 2,000 years. -

Events and Land Reform in Russia

3 TITLE: EVENKS AND LAND REFORM IN RUSSIA: PROGRESS AND OBSTACLES AUTHOR: GAIL FONDAHL University of Northern British Columbia THE NATIONAL COUNCIL FOR SOVIET AND EAST EUROPEAN RESEARCH TITLE VIII PROGRAM 1755 Massachusetts Avenue, N.W. Washington, D.C. 20036 PROJECT INFORMATION:1 CONTRACTOR: Dartmouth College PRINCIPAL INVESTIGATOR: Gail Fondahl COUNCIL CONTRACT NUMBER: 808-28 DATE: March 1, 1996 COPYRIGHT INFORMATION Individual researchers retain the copyright on work products derived from research funded by Council Contract. The Council and the U.S. Government have the right to duplicate written reports and other materials submitted under Council Contract and to distribute such copies within the Council and U.S. Government for their own use, and to draw upon such reports and materials for their own studies; but the Council and U.S. Government do not have the right to distribute, or make such reports and materials available, outside the Council or U.S. Government without the written consent of the authors, except as may be required under the provisions of the Freedom of Information Act 5 U.S.C. 552, or other applicable law. 1 The work leading to this report was supported in part by contract funds provided by the National Council for Soviet and East European Research, made available by the U. S. Department of State under Title VIII (the Soviet-Eastern European Research and Training Act of 1983, as amended). The analysis and interpretations contained in the report are those of the author(s). EVENKS AND LAND REFORM IN RUSSIA: PROGRESS AND OBSTACLES Gail Fondahl1 The Evenks are one of most populous indigenous peoples of Siberia (with 30,247 individuals, according to a 1989 census), inhabiting an area stretching from west of the Yenisey River to the Okhotsk seaboard and Sakhalin Island, and from the edge of the tundra south to China and Mongolia. -

National Minorities in Lithuania, a Study Visit

National Minorities in Lithuania; A study visit to Vilnius and Klaipėda for Mercator Education 7-14 November 2006 Tjeerd de Graaf and Cor van der Meer Introduction The Mercator-Education project hosted at the Frisian Academy has been established with the principal goal of acquiring, storing and disseminating information on minority and regional language education in the European region 1. Recently a computerised database containing bibliographic data, information about people and organisations involved in this subject has been established. The series of Regional Dossiers published by Mercator-Education provides descriptive information about minority languages in a specific region of the European Union, such as characteristics of the educational system and recent educational policies. At present, an inventory of the languages in the new states of the European Union is being made showing explicitly the position of ethnic minorities. In order to investigate the local situation in one of these new states in more detail and to inform representatives of the communities about the work of Mercator Education and the policies of the European Union in this field, a delegation from the Frisian Academy visited Lithuania in the week 7-14 November 2006. Together with Lithuanian colleagues a program for this visit was prepared according to the following schedule. Schedule of the study trip to Lithuania 7 – 14 November 2006 Tuesday 7 November: Arrival in Vilnius at 13:25 with TE465 16:00 Meeting at the Department of National Minorities and Lithuanians -

Bible Survey

Bible Survey Genesis The first book of the Bible is named Genesis or “beginning.” Genesis presents the divine origin of the world. This is not a scientific account of the beginning of the universe or of life. It is Israel’s faith statement of God’s activity in the origins of the universe and of mankind fundamental for our salvation. Genesis also provides an account of the beginnings of Israel and God’s call to Abraham, and his relatives, the Patriarchs. In Genesis the stage is set for salvation since it is here we are told of Creation, sin, and God’s first promises to save mankind. The book can be divided into two sections. The first section, chapters 1 through 11, present the story of Creation and the beginning of Israel’s salvation. The second section, chapters 12 through 50, introduce us to the Patriarchs, Abraham, Isaac, Jacob and Joseph. Exodus The second book of the Bible is called Exodus, from the Greek word for ‘departure,’ because its central event is the departure of the Israelites from Egypt. Exodus recounts the Egyptian oppression of Jacob’s ever-increasing descendants and their miraculous deliverance by God through Moses, who led them across the Red Sea to Mount Sinai where they received the Law entering into a covenant with the Lord. The Law, or Torah in Hebrew, constitutes the moral, civil, and ritual legislation by which the Israelites were to become a holy people. Many elements of the Law were fundamental to the teaching of Jesus as well as to New Testament and Christian moral teaching. -

2020 SBM Teshuvot “Dina D'malkhuta Dina: Obligations And

2020 SBM Teshuvot “Dina D’Malkhuta Dina: Obligations and Limits” Published by the Center for Modern Torah Leadership 1 Table of Contents Week One Summary: Dina Demalkhuta Dina: How Broad a Principle? 3 Week Two Summary: What Makes Taxation Halakhically Legitimate? 5 Week Three Summary: Does Halakhah Permit Taxation Without Representation? 8 Week Four Summary: Are Israeli Labor Laws Binding on Chareidi Schools? 11 Week Five Summary: Does Dina Demalkhuta Dina Apply in Democracies? 14 Week Six Summary: Introduction to the Sh’eilah 16 SBM 2020 Sh’eilah 17 State Authority and Religious Obligation – An Introduction 19 Teshuvah - Bracha Weinberger 23 Teshuvah - Talia Weisberg 26 Teshuvah - Avi Sommer 30 Teshuvah - Zack Orenshein 37 Teshuvah - Sara Schatz 41 Teshuvah - Batsheva Leah Weinstein 43 Teshuvah - Joshua Skootsky 48 Teshuvah - Eliana Yashgur 52 Teshuvah - Eli Putterman 55 Teshuvah - Akiva Weisinger 65 2 Week One Summary: Dina Demalkhuta Dina: How Broad a Principle? by Avi Sommer July 3, 2020 Mishnah Bava Kamma 113a places various restrictions on transactions with tax collectors on the ground that their coins are considered stolen. For example, one may not accept charity from tax collectors or ask them to change larger denominations. You may be wondering: why would someone having a private economic transaction with a tax collector receive coins collected as taxes in change? Likewise, how could tax collectors give tax money away as charity? Shouldn’t it all have been given to their government? The answer is that the governments with which Chaza”l interacted, such as the Roman Empire, would sell the right to collect taxes to private individuals.