Preface to the Paperback Edition: a Scholarly Update

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reading the Miraculous Powers of Japanese Poetry Spells, Truth Acts, and a Medieval Buddhist Poetics of the Supernatural

Japanese Journal of Religious Studies 32/: –33 © 2005 Nanzan Institute for Religion and Culture R. Keller Kimbrough Reading the Miraculous Powers of Japanese Poetry Spells, Truth Acts, and a Medieval Buddhist Poetics of the Supernatural The supernatural powers of Japanese poetry are widely documented in the lit- erature of Heian and medieval Japan. Twentieth-century scholars have tended to follow Orikuchi Shinobu in interpreting and discussing miraculous verses in terms of ancient (arguably pre-Buddhist and pre-historical) beliefs in koto- dama 言霊, “the magic spirit power of special words.” In this paper, I argue for the application of a more contemporaneous hermeneutical approach to the miraculous poem-stories of late-Heian and medieval Japan: thirteenth- century Japanese “dharani theory,” according to which Japanese poetry is capable of supernatural effects because, as the dharani of Japan, it contains “reason” or “truth” (kotowari) in a semantic superabundance. In the first sec- tion of this article I discuss “dharani theory” as it is articulated in a number of Kamakura- and Muromachi-period sources; in the second, I apply that the- ory to several Heian and medieval rainmaking poem-tales; and in the third, I argue for a possible connection between the magico-religious technology of Indian “Truth Acts” (saccakiriyā, satyakriyā), imported to Japan in various sutras and sutra commentaries, and some of the miraculous poems of the late- Heian and medieval periods. keywords: waka – dharani – kotodama – katoku setsuwa – rainmaking – Truth Act – saccakiriyā, satyakriyā R. Keller Kimbrough is an Assistant Professor of Japanese at Colby College. In the 2005– 2006 academic year, he will be a Visiting Research Fellow at the Nanzan Institute for Religion and Culture. -

The Case of Sugawara No Michizane in the ''Nihongiryaku, Fuso Ryakki'' and the ''Gukansho''

Ideology and Historiography : The Case of Sugawara no Michizane in the ''Nihongiryaku, Fuso Ryakki'' and the ''Gukansho'' 著者 PLUTSCHOW Herbert 会議概要(会議名, Historiography and Japanese Consciousness of 開催地, 会期, 主催 Values and Norms, カリフォルニア大学 サンタ・ 者等) バーバラ校, カリフォルニア大学 ロサンゼルス校, 2001年1月 page range 133-145 year 2003-01-31 シリーズ 北米シンポジウム 2000 International Symposium in North America 2014 URL http://doi.org/10.15055/00001515 Ideology and Historiography: The Case of Sugawara no Michizane in the Nihongiryaku, Fusi Ryakki and the Gukanshd Herbert PLUTSCHOW University of California at Los Angeles To make victims into heroes is a Japanese cultural phenomenon intimately relat- ed to religion and society. It is as old as written history and survives into modem times. Victims appear as heroes in Buddhist, Shinto, and Shinto-Buddhist cults and in numer- ous works of Japanese literature, theater and the arts. In a number of articles I have pub- lished on this subject,' I tried to offer a religious interpretation, emphasizing the need to placate political victims in order to safeguard the state from their wrath. Unappeased political victims were believed to seek revenge by harming the living, causing natural calamities, provoking social discord, jeopardizing the national welfare. Beginning in the tenth century, such placation took on a national importance. Elsewhere I have tried to demonstrate that the cult of political victims forced political leaders to worship their for- mer enemies in a cult providing the religious legitimization, that is, the mainstay of their power.' The reason for this was, as I demonstrated, the attempt leaders made to control natural forces through the worship of spirits believed to influence them. -

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} Sugawara No Michizane and the Early Heian Court by Robert Borgen Sugawara No Michizane and the Early Heian Court by Robert Borgen

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} Sugawara No Michizane and the Early Heian Court by Robert Borgen Sugawara No Michizane and the Early Heian Court by Robert Borgen. Our systems have detected unusual traffic activity from your network. Please complete this reCAPTCHA to demonstrate that it's you making the requests and not a robot. If you are having trouble seeing or completing this challenge, this page may help. If you continue to experience issues, you can contact JSTOR support. Block Reference: #1bc2a6c0-ce27-11eb-9f2b-9b289c5f10eb VID: #(null) IP: 116.202.236.252 Date and time: Tue, 15 Jun 2021 22:14:52 GMT. Sugawara No Michizane and the Early Heian Court by Robert Borgen. Our systems have detected unusual traffic activity from your network. Please complete this reCAPTCHA to demonstrate that it's you making the requests and not a robot. If you are having trouble seeing or completing this challenge, this page may help. If you continue to experience issues, you can contact JSTOR support. Block Reference: #1bc34300-ce27-11eb-8fa9-d3dc48c977eb VID: #(null) IP: 116.202.236.252 Date and time: Tue, 15 Jun 2021 22:14:53 GMT. Sugawara no Michizane and the early Heian court. Places: Japan Subjects: Sugawara, Michizane, 845-903., Statesmen -- Japan -- Biography., Japan -- History -- Heian period, 794-1185. Edition Notes. Includes bibliographical references (p. 375-402) and indexes. Statement Robert Borgen. Classifications LC Classifications DS856.72.S9 B67 1994 The Physical Object Pagination xxiii, 431 p. : Number of Pages 431 ID Numbers Open Library OL1425950M ISBN 10 0824815904 LC Control Number 93036993. Sugawara no Michizane was an excellent student and scholar. -

Volume 23 (2016), Article 3

Volume 23 (2016), Article 3 http://chinajapan.org/articles/23/3 Williams, Nicholas Morrow, “Being Alive: Doctrine versus Experience in the Writings of Yamanoue no Okura” Sino-Japanese Studies 23 (2016), article 3. Abstract: Yamanoue no Okura’s 山上憶良 (660–733?) writings in the Man’yōshū 萬葉集 anthology present unique challenges of linguistic and literary-historical reconstruction. Composed in various permutations of man’yōgana and logographic script and also in Chinese (kanbun), Okura’s texts are replete with allusions to Chinese texts ranging from the Confucian canon to apocryphal Buddhist sutras and popular anthologies, many of which are lost or survive only in Dunhuang manuscripts. But the technical challenges in approaching Okura’s writings should not blind us to the spirit of skeptical self-awareness that underlie these literary artifacts. Okura frequently cites the spiritual doctrines contained in his Chinese sources: the overcoming of suffering in Buddhist scripture, the perfection of the body through Daoist practices, or the ethical responsibilities set out in Confucian teachings. But he has a singular practice of partial or misleading quotation: borrowing scattered fragments of philosophy or religion, but reusing them to shape singular representations of his own experience. This article will first present an overview of Okura’s extant works as contained in the Man’yōshū anthology, as well as the primary Chinese sources that seem to have influenced him. The next three sections analyze particular works of Okura in light of their Chinese intertexts, roughly organized around their Buddhist, Daoist, or Confucian orientations. The conclusion offers some tentative indications of how Okura’s distinctive reactions to his sources influenced his own literary style, and also regarding Okura’s legacy for Japanese letters. -

The Zen Poems of Ryokan PRINCETON LIBRARY of ASIAN TRANSLATIONS Advisory Committee for Japan: Marius Jansen, Ear! Miner, Janies Morley, Thomas J

Japanese Linked Poetry An Account unih Translations of Rcnga and Haikai Sequences PAUL MINER As the link between the court poetry of the classical period and the haiku poetry of the modern period, the rcnga and haikai which constitute Japanese linked poetry have a position of central im portance in Japanese literature. This is the first comprehensive study of this major Japanese verse form in a Western language, and includes the critical principles of linked poetry, its placement in the history of Japanese literature, and an analysis of two renga and four haikai sequences in annotated translation. “The significance of the book as a pioneering work cannot be overemphasized. .. We should be grateful to the author for his lucid presentation of this difficult subject.” — The Journal of Asian Studies Cloth: ISBN 06372-9. Paper: ISBN 01368-3. 376 pages. 1978. The Modern Japanese Prose Poem An Anthology of Six Poets Translated and with an Introduction by DENNIS KEENE “Anyone interested in modern Japanese poetry, and many in volved in comparative literature, will want to own this work.” — Montmenta Nipponica Though the prose poem came into existence as a principally French literary genre in the nineteenth century, it occupies a place of considerable importance in twentieth-century Japanese poetry. This selection of poems is the first anthology of this gcurc and, in effect, the first appearance of this kind of poetry in English. Providing a picture of the last fifty years or so of Japanese poetry, the anthology includes poems by Miyoshi Tat- suji and Anzai Fuyue, representing the modernism of the prewar period; Tamura Ryuichi and Yoshioka Minoru, representing the post-war period; and Tanikawa Shuntaro and Inoue Yashushi, representing the present. -

EARLY MODERN JAPAN FALL, 2003 the Evening Banter of Two Tanu-Ki

EARLY MODERN JAPAN FALL, 2003 The Evening Banter of Two part of bungaku in Renku nyūmon.4 Tanu-ki: Reading the Tobi Haikai no renga texts are the product of two or 1 more poets composing together according to a set Hiyoro Sequence of rules.5 One approach to them has been to concentrate on an individual link, often reading it ©Scot Hislop, Japan Society for the Pro- as the expression of the self of the poet who composed it. This approach, however, fails to motion of Science Fellow, National Mu- take into account the rules, the interactions, and seum of Japanese History the creation of something akin to Bakhtin’s 2 dialogic voice in the production of a linked-verse Although haikai no renga was central to the sequence. poetic practice of haikai poets throughout the Edo Another approach is to treat haikai no renga period, its status within the canon of Japanese texts as intertexts. In a set of seminal essays and literature has been problematic since Masaoka 3 lectures now collected under the title Za no Shiki declared that it was not bungaku. bungaku, Ogata Tsutomu developed a set of Although Shiki admitted that haikai no renga concepts that are helpful when reading haikai texts had “literary” elements, linked verse values texts as intertexts.6 In this paper I will use change over unity so his final judgment was that Ogata’s concept of za no bungaku to look at a it could not be considered a part of bungaku. haikai no renga sequence composed by Although haikai no renga texts are now clearly Kobayashi Issa7 and Kawahara Ippyō.8 Ogata's read -

Kanshi, Haiku and Media in Meiji Japan, 1870-1900

The Poetry of Dialogue: Kanshi, Haiku and Media in Meiji Japan, 1870-1900 Robert James Tuck Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2012 © 2012 Robert Tuck All Rights Reserved ABSTRACT The Poetry of Dialogue: Kanshi, Haiku and Media in Meiji Japan, 1870-1900 Robert Tuck This dissertation examines the influence of ‘poetic sociality’ during Japan’s Meiji period (1867-1912). ‘Poetic sociality’ denotes a range of practices within poetic composition that depend upon social interaction among individuals, most importantly the tendency to practice poetry as a group activity, pedagogical practices such as mutual critique and the master-disciple relationship, and the exchange among individual poets of textually linked forms of verse. Under the influence of modern European notions of literature, during the late Meiji period both prose fiction and the idea of literature as originating in the subjectivity of the individual assumed hegemonic status. Although often noted as a major characteristic of pre-modern poetry, poetic sociality continued to be enormously influential in the literary and social activities of 19th century Japanese intellectuals despite the rise of prose fiction during late Meiji, and was fundamental to the way in which poetry was written, discussed and circulated. One reason for this was the growth of a mass-circulation print media from early Meiji onward, which provided new venues for the publication of poetry and enabled the expression of poetic sociality across distance and outside of face-to-face gatherings. With poetic exchange increasingly taking place through newspapers and literary journals, poetic sociality acquired a new and openly political aspect. -

Biographies of Sugawara No Michizane and the Praxis of Heian Sinitic Poetry

九州大学学術情報リポジトリ Kyushu University Institutional Repository Michizane’s Other Exile? Biographies of Sugawara no Michizane and the Praxis of Heian Sinitic Poetry VAN DER SALM, NIELS Leiden University, Skill Lecturer in Japanese https://doi.org/10.5109/4377707 出版情報:Journal of Asian Humanities at Kyushu University. 6, pp.61-83, 2021-03. 九州大学文学 部大学院人文科学府大学院人文科学研究院 バージョン: 権利関係: Michizane’s Other Exile? Biographies of Sugawara no Michizane and the Praxis of Heian Sinitic Poetry NIELS VAN DER SALM 更妬他人道左遷 What’s even more upsetting is how others speak of my “demotion.” Sugawara no Michizane, Kanke bunsō, fasc. 3 Introduction cession and sent into exile in Dazaifu 太宰府, where he died in ignominy two years later. This line, however, was arly Heian court scholar, poet, and official, written fifteen years earlier, in the first month of 886. In Sugawara no Michizane 菅原道真 (845–903), that year, Michizane was transferred from his post in in a poem preserved in his personal literary col- the Bureau for Higher Learning (Daigakuryō 大学寮), Election Kanke bunsō 菅家文草 (The Sugawara Liter- the institution tasked with the education of the court’s ary Drafts), thus described being upset about rumors professional bureaucracy, to the island of Shikoku, concerning his demotion—a common euphemism for where he was to serve a four-year term as Governor of “exile” (sasen 左遷, K187).1 As is well known, in 901 Sanuki 讃岐 Province.2 What made Michizane describe Michizane was accused of interference in the royal suc- this appointment in such strong terms? This question has occupied numerous scholars for the better part of a century and has produced a sizeable literature with I would like to express my gratitude to Tina Dermois, Dario Min- interpretations ranging from Michizane’s righteous in- guzzi (La Sapienza University of Rome), and Bruce Winkelman (University of Chicago) for reading and discussing earlier drafts dignation at political elimination to exaggerated lament of this article. -

He Arashina Iary

!he "arashina #iary h A WOMAN’S LIFE IN ELEVENTH-CENTURY JAPAN READER’S EDITION ! ! SUGAWARA NO TAKASUE NO MUSUME TRANSLATED, WITH AN INTRODUCTION, BY SONJA ARNTZEN AND ITŌ MORIYUKI Columbia University Press New York Columbia University Press Publishers Since New York Chichester, West Sussex cup .columbia .edu Copyright © Columbia University Press All rights reserved Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Sugawara no Takasue no Musume, – author. | Arntzen, Sonja, – translator. | Ito, Moriyuki, – translator. Title: *e Sarashina diary : a woman’s life in eleventh-century Japan / Sugawara no Takasue no Musume ; translated, with an introduction, by Sonja Arntzen and Ito Moriyuki. Other titles: Sarashina nikki. English Description: Reader’s edition. | New York : Columbia University Press, [] | Series: Translations from the Asian classics | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: LCCN (print) | LCCN (ebook) | ISBN (electronic) | ISBN (cloth : alk. paper) | ISBN (pbk. : acid-free paper) Subjects: LCSH: Sugawara no Takasue no Musume, —Diaries. | Authors, Japanese—Heian period, –—Diaries. | Women— Japan—History—To . Classification: LCC PL.S (ebook) | LCC PL.S Z (print) | DDC ./ [B] —dc LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/ Columbia University Press books are printed on permanent and durable acid-free paper. Printed in the United States of America Cover design: Lisa Hamm Cover image: A bi-fold screen by calligrapher Shikō Kataoka (–). CONTENTS Preface to the Reader’s Edition vii Introduction xi Sarashin$ Diar% Appendix . Family and Social Connections Appendix . Maps Appendix . List of Place Names Mentioned in the Sarashina Diary Notes Bibliography Index PREFACE TO THE READER’S EDITION he Sarashina Diary: A Woman’s Life in Eleventh-Century Japan was published in . -

Heian Court Poetry-1.Indd

STRUMENTI PER LA DIDATTICA E LA RICERCA – 159 – FLORIENTALIA Asian Studies Series – University of Florence Scientific Committee Valentina Pedone, Coordinator, University of Florence Sagiyama Ikuko, Coordinator, University of Florence Alessandra Brezzi, University of Rome “La Sapienza” Marco Del Bene, University of Rome “La Sapienza” Paolo De Troia, University of Rome “La Sapienza” Fujiwara Katsumi, University of Tokyo Guo Xi, Jinan University Hyodo Hiromi, Gakushuin University Tokyo Federico Masini, University of Rome “La Sapienza” Nagashima Hiroaki, University of Tokyo Chiara Romagnoli, Roma Tre University Bonaventura Ruperti, University of Venice “Ca’ Foscari” Luca Stirpe, University of Chieti-Pescara “Gabriele d’Annunzio” Tada Kazuomi, University of Tokyo Massimiliano Tomasi, Western Washington University Xu Daming, University of Macau Yan Xiaopeng, Wenzhou University Zhang Xiong, Peking University Zhou Yongming, University of Wisconsin-Madison Published Titles Valentina Pedone, A Journey to the West. Observations on the Chinese Migration to Italy Edoardo Gerlini, The Heian Court Poetry as World Literature. From the Point of View of Early Italian Poetry Ikuko Sagiyama, Valentina Pedone (edited by), Perspectives on East Asia Edoardo Gerlini The Heian Court Poetry as World Literature From the Point of View of Early Italian Poetry Firenze University Press 2014 The Heian Court Poetry as World Literature : From the Point of View of Early Italian Poetry / Edoardo Gerlini. – Firenze : Firenze University Press, 2014. (Strumenti per la didattica e la ricerca ; 159) http://digital.casalini.it/9788866556046 ISBN 978-88-6655-600-8 (print) ISBN 978-88-6655-604-6 (online PDF) Progetto grafico di Alberto Pizarro Fernández, Pagina Maestra snc Peer Review Process All publications are submitted to an external refereeing process under the responsibility of the FUP Editorial Board and the Scientific Committees of the individual series. -

1 “Dimitrie Cantemir”

“DIMITRIE CANTEMIR” CHRISTIAN UNIVERSITY FACULTY OF FOREIGN LANGUAGES AND LITERATURES ANNALS OF “DIMITRIE CANTEMIR” CHRISTIAN UNIVERSITY LINGUISTICS, LITERATURE AND METHODOLOGY OF TEACHING VOLUME XVII No.1/2018 1 This journal is included in IDB SCIPIO CEEOL ICI Journals Master List 2016 http://analeflls.ucdc.ro [email protected] ISSN 2065 - 0868 ISSN-L 2065 - 0868 Each author is responsible for the originality of his article and the fact that it has not been previously published. 2 “DIMITRIE CANTEMIR” CHRISTIAN UNIVERSITY FACULTY OF FOREIGN LANGUAGES AND LITERATURES ANNALS OF “DIMITRIE CANTEMIR” CHRISTIAN UNIVERSITY LINGUISTICS, LITERATURE AND METHODOLOGY OF TEACHING VOLUME XVII No.1/2018 3 “DIMITRIE CANTEMIR” CHRISTIAN UNIVERSITY BOARD Momcilo Luburici President Corina Adriana Dumitrescu President of the Senate Cristiana Cristureanu Rector Georgeta Ilie Vice-Rector for Scientific Research EDITORIAL ADVISORY BOARD Florentina Alexandru Dimitrie Cantemir Christian University Nicolae Dobrisan Corresponding Member of Cairo Arabic Language Academy and of The Syrian Science Academy Damascus Mary Koutsoudaki University of Athens Greg Kucich Notre Dame University Dana Lascu University of Richmond Ramona Mihaila Dimitrie Cantemir Christian University Emma Morita Kindai University Efstratia Oktapoda Sorbonne, Paris IV University Julieta Paulesc Arizona State University Elena Prus Free International University of Moldova Marius Sala Romanian Academy Silvia Tita University of Michigan Irina Mihai-Vainovski Dimitrie Cantemir Christian University Estelle -

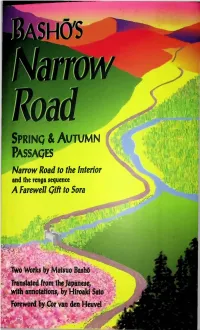

Spring &Autumn

Spring & Autumn Passages Narrow Road to the Interior and the renga sequence A Farewell Qift to Sora iV-y, . p^: Two Works by Matsuo BasM Translated from the Japanese, with annotations, by Hiroaki Sato Foreword by Cor van den Heuvel '-f BASHO'S NARROW ROAD i j i ; ! ! : : ! I THE ROCK SPRING COLLECTION OF JAPANESE LITERATURE ; BaSHO'S Narrow Road SPRINQ & AUTUMN PASSAQES Narrow Road to the Interior AND THE RENGA SEQUENCE A Farewell Gift to Sora TWO WORKS BY MATSUO BASHO TRANSLATED FROM THE JAPANESE, WITH ANNOTATIONS, BY Hiroaki Sato FOREWORD BY Cor van den Heuvel STONE BRIDGE PRESS • Berkeley,, California Published by Stone Bridge Press, P.O, Box 8208, Berkeley, CA 94707 510-524-8732 • [email protected] • www.stoncbridgc.com Cover design by Linda Thurston. Text design by Peter Goodman. Text copyright © 1996 by Hiroaki Sato. Signature of the author on front part-title page: “Basho.” Illustrations by Yosa Buson reproduced by permission of Itsuo Museum. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form without permission from the publisher. Printed in the United States of America 10 987654321 LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOG1NG-1N-PUBL1 CATION DATA Matsuo, BashO, 1644-1694. [Oku no hosomichi. English] Basho’s Narrow road: spring and autumn passages: two works / by Matsuo Basho: translated from the Japanese, with annotations by Hiroaki Sato. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. Contents: Narrow road to the interior and the renga sequence—A farewell gift to Sora. ISBN 1-880656-20-5 (pbk.) 1- Matsuo, Basho, 1644-1694—Journeys—Japan.