Kanshi, Haiku and Media in Meiji Japan, 1870-1900

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The University of Chicago Tears in the Imperial Screen

THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO TEARS IN THE IMPERIAL SCREEN: WARTIME COLONIAL KOREAN CINEMA, 1936-1945 A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE DIVISION OF THE HUMANITIES IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY DEPARTMENT OF EAST ASIAN LANGUAGES AND CIVILIZATIONS BY HYUN HEE PARK CHICAGO, ILLINOIS AUGUST 2017 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page LIST OF TABLES ...…………………..………………………………...……… iii LIST OF FIGURES ...…………………………………………………..……….. iv ABSTRACT ...………………………….………………………………………. vi CHAPTER 1 ………………………..…..……………………………………..… 1 INTRODUCTION CHAPTER 2 ……………………………..…………………….……………..… 36 ENLIGHTENMENT AND DISENCHANTMENT: THE NEW WOMAN, COLONIAL POLICE, AND THE RISE OF NEW CITIZENSHIP IN SWEET DREAM (1936) CHAPTER 3 ……………………………...…………………………………..… 89 REJECTED SINCERITY: THE FALSE LOGIC OF BECOMING IMPERIAL CITIZENS IN THE VOLUNTEER FILMS CHAPTER 4 ………………………………………………………………… 137 ORPHANS AS METAPHOR: COLONIAL REALISM IN CH’OE IN-GYU’S CHILDREN TRILOGY CHAPTER 5 …………………………………………….…………………… 192 THE PLEASURE OF TEARS: CHOSŎN STRAIT (1943), WOMAN’S FILM, AND WARTIME SPECTATORSHIP CHAPTER 6 …………………………………………….…………………… 241 CONCLUSION BIBLIOGRAPHY …………………………………………………………….. 253 FILMOGRAPHY OF EXTANT COLONIAL KOREAN FILMS …………... 265 ii LIST OF TABLES Page Table 1. Newspaper articles regarding traffic film screening events ………....…54 Table 2. Newspaper articles regarding traffic film production ……………..….. 56 iii LIST OF FIGURES Page Figure. 1-1. DVDs of “The Past Unearthed” series ...……………..………..…..... 3 Figure. 1-2. News articles on “hygiene film screening” in Maeil sinbo ….…... 27 Figure. 2-1. An advertisement for Sweet Dream in Maeil sinbo……………… 42 Figure. 2-2. Stills from Sweet Dream ………………………………………… 59 Figure. 2-3. Stills from the beginning part of Sweet Dream ………………….…65 Figure. 2-4. Change of Ae-sun in Sweet Dream ……………………………… 76 Figure. 3-1. An advertisement of Volunteer ………………………………….. 99 Figure. 3-2. Stills from Volunteer …………………………………...……… 108 Figure. -

Focus Asia Subscribe for Free Direct to Your Inbox Every Week Anzbloodstocknews.Com/Asia

FOCUS ASIA SUBSCRIBE FOR FREE DIRECT TO YOUR INBOX EVERY WEEK ANZBLOODSTOCKNEWS.COM/ASIA Wednesday, June 9, 2021 | Dedicated to the Australasian bloodstock industry - subscribe for free: Click here STEVE MORAN - PAGE 13 FOCUS ASIA - PAGE 11 Valuable mare Tofane Read Tomorrow's Issue For It's In The Blood could still be on the market What's on Winter carnival to determine whether daughter of Ocean Park Metropolitan meetings: Canterbury races on next season (NSW), Belmont (WA) Race Meetings: Sale (VIC), Sunshine Coast (QLD), Strathalbyn (SA), Matamata (NZ) Barrier trials / Jump-outs: Kembla Grange (NSW), Pakenham (VIC), Mornington (VIC), Wangaratta (VIC) International meetings: Happy Valley (HK), Hamilton (UK), Haydock (UK), Kempton (UK), Yarmouth (UK), Cork (IRE), Lyon (FR) Sales: Inglis Digital June (Early) Sale International Sales: OBS June 2YOs and Horses of Racing Age (USA) Toofane RACING PHOTOS Coast auction last month, ran on well to finish BY TIM ROWE | @ANZ_NEWS runner-up to Emerald Kingdom (Bryannbo’s MORNING BRIEFING tradbroke Handicap (Gr 1, 1400m) Gift) in the BRC Sprint (Gr 3, 1350m) on May contender Tofane (Ocean Park), 22, a performance that convinced her owners Oaks winner Personal to whose racetrack career was extended to race her on during the Queensland winter race in the US after connections gave up a gilt- carnival. VRC Oaks (Gr 1, 2500m) winner Personal (Fastnet Sedged opportunity to sell the valuable mare at “There’s no doubt that she was highly sought Rock) is moving to the US to be trained in New the Magic Millions National Broodmare Sale, after. We had a lot of enquiry for her leading into York by Chad Brown. -

Western Literature in Japanese Film (1910-1938) Alex Pinar

ADVERTIMENT. Lʼaccés als continguts dʼaquesta tesi doctoral i la seva utilització ha de respectar els drets de la persona autora. Pot ser utilitzada per a consulta o estudi personal, així com en activitats o materials dʼinvestigació i docència en els termes establerts a lʼart. 32 del Text Refós de la Llei de Propietat Intel·lectual (RDL 1/1996). Per altres utilitzacions es requereix lʼautorització prèvia i expressa de la persona autora. En qualsevol cas, en la utilització dels seus continguts caldrà indicar de forma clara el nom i cognoms de la persona autora i el títol de la tesi doctoral. No sʼautoritza la seva reproducció o altres formes dʼexplotació efectuades amb finalitats de lucre ni la seva comunicació pública des dʼun lloc aliè al servei TDX. Tampoc sʼautoritza la presentació del seu contingut en una finestra o marc aliè a TDX (framing). Aquesta reserva de drets afecta tant als continguts de la tesi com als seus resums i índexs. ADVERTENCIA. El acceso a los contenidos de esta tesis doctoral y su utilización debe respetar los derechos de la persona autora. Puede ser utilizada para consulta o estudio personal, así como en actividades o materiales de investigación y docencia en los términos establecidos en el art. 32 del Texto Refundido de la Ley de Propiedad Intelectual (RDL 1/1996). Para otros usos se requiere la autorización previa y expresa de la persona autora. En cualquier caso, en la utilización de sus contenidos se deberá indicar de forma clara el nombre y apellidos de la persona autora y el título de la tesis doctoral. -

Reading the Miraculous Powers of Japanese Poetry Spells, Truth Acts, and a Medieval Buddhist Poetics of the Supernatural

Japanese Journal of Religious Studies 32/: –33 © 2005 Nanzan Institute for Religion and Culture R. Keller Kimbrough Reading the Miraculous Powers of Japanese Poetry Spells, Truth Acts, and a Medieval Buddhist Poetics of the Supernatural The supernatural powers of Japanese poetry are widely documented in the lit- erature of Heian and medieval Japan. Twentieth-century scholars have tended to follow Orikuchi Shinobu in interpreting and discussing miraculous verses in terms of ancient (arguably pre-Buddhist and pre-historical) beliefs in koto- dama 言霊, “the magic spirit power of special words.” In this paper, I argue for the application of a more contemporaneous hermeneutical approach to the miraculous poem-stories of late-Heian and medieval Japan: thirteenth- century Japanese “dharani theory,” according to which Japanese poetry is capable of supernatural effects because, as the dharani of Japan, it contains “reason” or “truth” (kotowari) in a semantic superabundance. In the first sec- tion of this article I discuss “dharani theory” as it is articulated in a number of Kamakura- and Muromachi-period sources; in the second, I apply that the- ory to several Heian and medieval rainmaking poem-tales; and in the third, I argue for a possible connection between the magico-religious technology of Indian “Truth Acts” (saccakiriyā, satyakriyā), imported to Japan in various sutras and sutra commentaries, and some of the miraculous poems of the late- Heian and medieval periods. keywords: waka – dharani – kotodama – katoku setsuwa – rainmaking – Truth Act – saccakiriyā, satyakriyā R. Keller Kimbrough is an Assistant Professor of Japanese at Colby College. In the 2005– 2006 academic year, he will be a Visiting Research Fellow at the Nanzan Institute for Religion and Culture. -

Haiku Attunement & the “Aha” Moment

Special Article Haiku Attunement & the “Aha” Moment By Edward Levinson Author Edward Levinson As a photographer and writer living, working, and creating in Japan spring rain for 40 years, I like to think I know it well. However, since I am not an washing heart academic, the way I understand and interpret the culture is spirit’s kiss intrinsically visual. Smells and sounds also play a big part in creating my experiences and memories. In essence, my relationship with Later this haiku certainly surprised a Japanese TV reporter who Japan is conducted making use of all the senses. And this is the was covering a “Haiku in English” meeting in Tokyo where I read it. perfect starting point for composing haiku. Later it appeared on the evening news, an odd place to share my Attunement to one’s surroundings is important when making inner life. photographs, both as art and for my editorial projects on Japanese PHOTO 1: Author @Edward Levinson culture and travel. The power of the senses influences my essays and poetry as well. In haiku, with its short three-line form, the key to success is to capture and share the sensual nature of life, both physical and philosophical. For me, the so-called “aha” moment is the main ingredient for making a meaningful haiku. People often comment that my photos and haiku create a feeling of nostalgia. An accomplished Japanese poet and friend living in Hokkaido, Noriko Nagaya, excitedly telephoned me one morning after reading my haiku book. Her insight was that my haiku visions were similar to the way I must see at the exact moment I take a photo. -

Rhyming Pattern Selection in Japanese Short Poetry

Original Paper________________________________________________________ Forma, 21, 259–273, 2006 Statistical Prosody: Rhyming Pattern Selection in Japanese Short Poetry Kazuya HAYATA Department of Socio-Informatics, Sapporo Gakuin University, Ebetsu 069-8555, Japan E-mail address: [email protected] (Received August 5, 2005; Accepted August 2, 2006) Keywords: Quantitative Poetics, Rhyme, HAIKU, TANKA, Bell Number Abstract. Rhyme patterns of Japanese short poetry such as HAIKU, SENRYU, SEDOKAs, and TANKAs are analyzed by a statistical approach. Here HAIKU and SENRYU are poems composed of only seventeen syllables, which can be segmented into five, seven, and five syllables. As rhyming both head and end rhymes are considered. Analyses of sampled works of typical poets show that for the end rhyme composers prefere the avoided rhyming, whereas for the head rhyme they compose poems according to the stochastic law. Subsequently the statistical method is applied to a work of SEDOKAs as well as to those of TANKAs being written with three lines. Evaluation of the khi-square statistics shows that for a certain work of TANKAs the feature being identical to that of HAIKU is seen. 1. Introduction Irrespective of languages, texts are categorized into proses and verses. Poems, in general, take the form of the latter. Conventional poetics has classified poems into a variety of forms such as a lyric, an epic, a prose, a long, and a short poem. One finds that in typical European poetry a sound on a site in a line is correlated to that on the same site in another line in an established form. Correlation among feet of lines is termed end rhyme in contrast to the head rhyme for the one among heads of lines (SAKAMOTO, 2002). -

The Case of Sugawara No Michizane in the ''Nihongiryaku, Fuso Ryakki'' and the ''Gukansho''

Ideology and Historiography : The Case of Sugawara no Michizane in the ''Nihongiryaku, Fuso Ryakki'' and the ''Gukansho'' 著者 PLUTSCHOW Herbert 会議概要(会議名, Historiography and Japanese Consciousness of 開催地, 会期, 主催 Values and Norms, カリフォルニア大学 サンタ・ 者等) バーバラ校, カリフォルニア大学 ロサンゼルス校, 2001年1月 page range 133-145 year 2003-01-31 シリーズ 北米シンポジウム 2000 International Symposium in North America 2014 URL http://doi.org/10.15055/00001515 Ideology and Historiography: The Case of Sugawara no Michizane in the Nihongiryaku, Fusi Ryakki and the Gukanshd Herbert PLUTSCHOW University of California at Los Angeles To make victims into heroes is a Japanese cultural phenomenon intimately relat- ed to religion and society. It is as old as written history and survives into modem times. Victims appear as heroes in Buddhist, Shinto, and Shinto-Buddhist cults and in numer- ous works of Japanese literature, theater and the arts. In a number of articles I have pub- lished on this subject,' I tried to offer a religious interpretation, emphasizing the need to placate political victims in order to safeguard the state from their wrath. Unappeased political victims were believed to seek revenge by harming the living, causing natural calamities, provoking social discord, jeopardizing the national welfare. Beginning in the tenth century, such placation took on a national importance. Elsewhere I have tried to demonstrate that the cult of political victims forced political leaders to worship their for- mer enemies in a cult providing the religious legitimization, that is, the mainstay of their power.' The reason for this was, as I demonstrated, the attempt leaders made to control natural forces through the worship of spirits believed to influence them. -

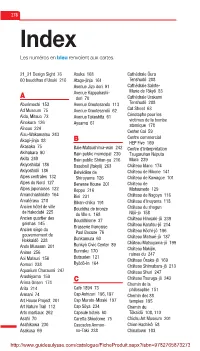

Index Du Guide

278 Index Les numéros en bleu renvoient aux cartes. 21_21 Design Sight 76 Asuka 168 Cathédrale Ôura 60 bouddhas d’Usuki 216 Atago-jinja 161 Tenshudô 208 Avenue Jizo dori 91 Cathédrale Sainte- Avenue Kappabashi- Marie de Tôkyô 83 A dori 70 Cathédrale Urakami Aburimochi 153 Avenue Omotesando 113 Tenshudô 208 Ad Museum 75 Avenue Omotesandô 62 Cat Street 63 Aida, Mitsuo 73 Avenue Takeshita 61 Cénotaphe pour les victimes de la bombe Ainokura 126 Ayoama 61 atomique 178 Aïnous 224 Center Gai 59 Aizu-Wakamatsu 243 B Centre commercial Akagi-jinja 88 HEP Five 169 Akasaka 75 Baie Matsushima-wan 242 Centre d’interprétation Akihabara 90 Bain public municipal 230 Tsugaruhan Néputa Akita 240 Bain public Shitan-yu 216 Mura 239 Akiyoshidai 186 Baseball (Yakyû) 263 Château blanc 174 Akiyoshidô 186 Belvédère de Château de Hikone 141 Alpes centrales 132 Shiroyama 126 Château de Kawagoe 101 Alpes du Nord 127 Benesse House 201 Château de Alpes japonaises 122 Beppu 216 Matsumoto 129 Amanohashidate 164 Biei 231 Château de Nagoya 116 Amatérasu 218 Bikan-chiku 191 Château d’Inuyama 118 Ancien hôtel de ville Bouddha de bronze Château du shogun de Hakodaté 225 du VIIe s. 168 Nijô-jo 158 Ancien quartier des Bouddhisme 37 Château Hirosaki-jô 239 geishas 145 Brasserie française Château Karatsu-jô 214 Ancien siège du Paul Bocuse 76 Château Kôchi-jô 196 gouvernement de Bunkamura 60 Château Matsué-jô 187 Hokkaidô 228 Château Matsuyama-jô 199 Ando Museum 201 Bunkyô Civic Center 89 Bunraku 170 Château Nakijin, Anime 256 ruines du 247 Butsuden 121 Aoi Matsuri 156 Château -

Description of Fences

Equestrian Park Equestrian 馬事公苑 馬術 / Sports équestres Parc Equestre Jumping Individual 障害馬術個人 / Saut d'obstacles individuel ) TUE 3 AUG 2021 Qualifier 予選 / Qualificative Description of Fences フェンスの説明 / Description des obstacles Fence 1 – RIO 2016 EQUO JUMPINDV----------QUAL000100--_03B 1 Report Created TUE 3 AUG 2021 17:30 Page 1/14 Equestrian Park Equestrian 馬事公苑 馬術 / Sports équestres Parc Equestre Jumping Individual 障害馬術個人 / Saut d'obstacles individuel ) TUE 3 AUG 2021 Qualifier 予選 / Qualificative Fence 2 – Tokyo Skyline Tōkyō Sukai Tsurī o 東京スカイツリ Sumida District, Tokyo The new Tokyo skyline has been eclipsed by the Sky Tree, the new communications tower in Tokyo, which is also the highest structure in all of Japan at 634 metres, and the highest communications tower in the world. The design of the superstructure is based on the following three concepts: . Fusion of futuristic design and traditional beauty of Japan, . Catalyst for revitalization of the city, . Contribution to disaster prevention “Safety and Security”. … combining a futuristic and innovating design with the traditional Japanese beauty, catalysing a revival of this part of the city and resistant to different natural disasters. The tower even resisted the 2011 earthquake that occurred in Tahoku, despite not being finished and its great height. EQUO JUMPINDV----------QUAL000100--_03B 1 Report Created TUE 3 AUG 2021 17:30 Page 2/14 Equestrian Park Equestrian 馬事公苑 馬術 / Sports équestres Parc Equestre Jumping Individual 障害馬術個人 / Saut d'obstacles individuel ) TUE 3 AUG 2021 Qualifier 予選 / Qualificative Fence 3 – Gold Repaired Broken Pottery Kintsugi, “the golden splice” The beauty of the scars of life. The “kintsugi” is a centenary-old technique used in Japan which dates of the second half of the 15th century. -

UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title The Lyric Forms of the Literati Mind: Yosa Buson, Ema Saikō, Masaoka Shiki and Natsume Sōseki Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/97g9d23n Author Mewhinney, Matthew Stanhope Publication Date 2018 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California The Lyric Forms of the Literati Mind: Yosa Buson, Ema Saikō, Masaoka Shiki and Natsume Sōseki By Matthew Stanhope Mewhinney A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Japanese Language in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Alan Tansman, Chair Professor H. Mack Horton Professor Daniel C. O’Neill Professor Anne-Lise François Summer 2018 © 2018 Matthew Stanhope Mewhinney All Rights Reserved Abstract The Lyric Forms of the Literati Mind: Yosa Buson, Ema Saikō, Masaoka Shiki and Natsume Sōseki by Matthew Stanhope Mewhinney Doctor of Philosophy in Japanese Language University of California, Berkeley Professor Alan Tansman, Chair This dissertation examines the transformation of lyric thinking in Japanese literati (bunjin) culture from the eighteenth century to the early twentieth century. I examine four poet- painters associated with the Japanese literati tradition in the Edo (1603-1867) and Meiji (1867- 1912) periods: Yosa Buson (1716-83), Ema Saikō (1787-1861), Masaoka Shiki (1867-1902) and Natsume Sōseki (1867-1916). Each artist fashions a lyric subjectivity constituted by the kinds of blending found in literati painting and poetry. I argue that each artist’s thoughts and feelings emerge in the tensions generated in the process of blending forms, genres, and the ideas (aesthetic, philosophical, social, cultural, and historical) that they carry with them. -

Central Sand Hills Ecological Landscape

Chapter 9 Central Sand Hills Ecological Landscape Where to Find the Publication The Ecological Landscapes of Wisconsin publication is available online, in CD format, and in limited quantities as a hard copy. Individual chapters are available for download in PDF format through the Wisconsin DNR website (http://dnr.wi.gov/, keyword “landscapes”). The introductory chapters (Part 1) and supporting materials (Part 3) should be downloaded along with individual ecological landscape chapters in Part 2 to aid in understanding and using the ecological landscape chapters. In addition to containing the full chapter of each ecological landscape, the website highlights key information such as the ecological landscape at a glance, Species of Greatest Conservation Need, natural community management opportunities, general management opportunities, and ecological landscape and Landtype Association maps (Appendix K of each ecological landscape chapter). These web pages are meant to be dynamic and were designed to work in close association with materials from the Wisconsin Wildlife Action Plan as well as with information on Wisconsin’s natural communities from the Wisconsin Natural Heritage Inventory Program. If you have a need for a CD or paper copy of this book, you may request one from Dreux Watermolen, Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources, P.O. Box 7921, Madison, WI 53707. Photos (L to R): Karner blue butterfly, photo by Gregor Schuurman, Wisconsin DNR; small white lady’s-slipper, photo by Drew Feldkirchner, Wisconsin DNR; ornate box turtle, photo by Rori Paloski, Wisconsin DNR; Fassett’s locoweed, photo by Thomas Meyer, Wisconsin DNR; spatterdock darner, photo by David Marvin. Suggested Citation Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources. -

Songs of the Righteous Spirit: “Men of High Purpose” and Their Chinese Poetry in Modern Japan MATTHEW FRALEIGH Brandeis University

Songs of the Righteous Spirit: “Men of High Purpose” and Their Chinese Poetry in Modern Japan MATTHEW FRALEIGH Brandeis University he term “men of high purpose” (shishi 志士) is most com- monly associated with a diverse group of men active in a wide rangeT of pro-imperial and nationalist causes in mid-nineteenth- century Japan.1 In a broader sense, the category of shishi embraces not only men of scholarly inclination, such as Fujita Tōko 藤田東湖, Sakuma Shōzan 佐久間象山, and Yoshida Shōin 吉田松陰, but also the less eru dite samurai militants who were involved in political assas sinations, attacks on foreigners, and full-fledged warfare from the 1850s through the 1870s. Before the Meiji Restoration, the targets of shishi activism included rival domains and the Tokugawa shogunate; after 1868, some disaffected shishi identified a new enemy in the early Meiji oligarchy (a group that was itself composed of many former shishi). Although they I have presented portions of my work on this topic at the Annual Meeting of the Associa- tion for Asian Studies, Boston, March 27, 2007, as well as at colloquia at the University of California, Los Angeles, and Brandeis University. On each occasion, I have benefited from the comments and questions of audience members. I would also like to thank in particu- lar the two anonymous reviewers of the manuscript, whose detailed comments have been immensely helpful. 1 I use Thomas Huber’s translation of the term shishi as “men of high purpose”; his article provides an excellent introduction to several major shishi actions in the 1860s.