From Romantic to Mimetic Fiction in Sir Gawain and the Green Knight

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sir Gawain and the Green Knight New Verse Translation by Benedict Flynn POETRY Read by Jasper Britton

Sir Gawain and the Green Knight New verse translation by Benedict Flynn POETRY Read by Jasper Britton NA286512D 1 I. When siege and assault had ceased... 1:47 2 This fair Britain, founded by that famous knight... 0:52 3 The king lay at Camelot one Christmas tide... 1:08 4 With New Year not yet a day old... 1:16 5 Now, Arthur would not eat until all were served... 0:58 6 So he stands, the stern young king... 1:06 7 I’ll say nothing more about the meal... 1:12 8 Green, were both the garments and the grinning man... 1:31 9 Garbed in green was the gallant rider... 1:27 10 And yet he had no helm or hauberk either... 1:38 11 Stunned, the court stared... 1:00 12 From the dais Arthur watched... 1:34 13 ‘Fight? Have no worry.’ 1:28 14 If he astonished them first... 1:21 15 ‘By heaven,’ said Arthur... 0:53 16 ‘Grant me grace,’ said Gawain... 1:06 17 The king commanded the courtly knight to stand. 1:12 18 ‘By God,’ said the Green Knight... 1:24 19 The Green Knight stood... 1:30 20 For he held the head up high in both his hands... 1:29 21 And yet high-born Arthur was heavy at heart... 1:25 22 II. Arthur was granted his gift of adventure... 1:29 23 So comes the summer season... 1:10 2 24 Yet he lingers till All Hallows... 1:26 25 He dwelt there that day.. -

The Hero with Three Faces

Wilfrid Laurier University Scholars Commons @ Laurier Theses and Dissertations (Comprehensive) 1974 The Hero With Three Faces Rebecca Susanne Larson Wilfrid Laurier University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.wlu.ca/etd Part of the English Language and Literature Commons, and the Religion Commons Recommended Citation Larson, Rebecca Susanne, "The Hero With Three Faces" (1974). Theses and Dissertations (Comprehensive). 1523. https://scholars.wlu.ca/etd/1523 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Scholars Commons @ Laurier. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations (Comprehensive) by an authorized administrator of Scholars Commons @ Laurier. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ABSTRACT THE HERO WITH THRF.F. FACES By REBECCA SUSANNF. LARSON A study of the relationship between myth and litera ture in relation to: 1) the origin and form of myth as literature developed through the Legend of King Arthur; and 2) the function of myth as literature tracing Dr. Philip Potter's motif of salvation through the novels Zorba the Greek, Don Quixote and The Once and Future King. 1 THE HERO WITH THREE FACES By REBECCA SUSANNE LARSON B.A. Waterloo Lutheran University, 1971 THESIS Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Arts deqree Wilfrid Laurier University 1974 Examining Committee Dr. Lawrence Toombs Dr. Aarne Siirala Dr. Eduard Riegert ii UMI Number: EC56506 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent on the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. -

Sir Gawain and the Green Knight: Not Really a Chivalric Romance Mladen M

Sir Gawain and the Green Knight: Not Really a Chivalric Romance Mladen M. Jakovljević University in Kosovska Mitrovica, Faculty of Philosophy, Department of English, Filipa Višnjića bb, 38220 Kosovska Mitrovica, Serbia [email protected] Vladislava S. Gordić Petković University of Novi Sad, Faculty of Philosophy, Department of English Studies, Dr Zorana Djindjića 2, 21101 Novi Sad, Serbia [email protected] Medieval English romance Sir Gawain and the Green Knight is unique not only in its form, content and structure, but also in the poet’s skillful use of conventions that play with the reader’s expectations by introducing elements that make the poem exquisitely ambivalent and place it in the fuzzy area where reality and fiction overlap. Although the poem seemingly praises the strength and purity of chivalry and knighthood, it actually subtly criticizes and comments on their failure when practiced outside the court and in real life. This is particularly noticeable when the poem’s symbolism, its hero, and the society he comes from are read against historical context, i.e. as reflections of the realities of medieval life. Accordingly, Sir Gawain and the Green Knight can be read as a poem that praises chivalry and knighthood more by way of commenting on their dissipation than through overt affirmation, as the future of the kingdom, its rulers and society, with its faulty Christian knights, is far from bright, given the cracks and flaws that mar its seemingly glossy façade. Keywords: English literature / medieval romance / Sir Gawain and the Green Knight / love / knighthood / chivalry Sir Gawain and the Green Knight is one of the best medieval English romances and also one of the most unconventional. -

Vilain, Auctor : the Upward Flow of Wisdom in Sir Gawain and the Green Knight / by Gail Althea Bell.

Yf LAIN, AUCTOR: THE UPWARD PLOW OF VfSCCfl IW SIR GABAfN AMD TRE GREEN KNIGHT -m __I- -- I-_.-- ---- Gail Althea Bell THESIS SUBHXTTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLHENT Of THE REQUIREHENTS FCR THE DEGREE OF RASTER OF ARTS in the Departaent English C Gail Althea Bell 1981 SISCN FRASEX UNXVERSITP October 198 1 A11 rights reserved, This thesis may not be reproduced i~whale or in part, by photocopy or other meaos, without permission of the author, APPROVAL NAME: Gail A1 thea BELL DEGREE: Master of Arts TITLE OF THESIS: Vilain Auctor: The Upward Flow of Wisdom in Sir Gawain and the Green Knight. EXAMINING COMMITTEE: Chai rman: Dr. Michael Steig Dr. Joseph Gal 1agher, 'Senior Supervi sor Associate Professor of Engl ish Dr. dary-~nnStouck, Assistant Professor of Engl ish Dr. Harvey De i ROO, Assistant Professor of Engl ish Dr. Kieran Kealy , ~xtehalExaminer Professor of English, U.B.C. Date Approved: 3/81. PARTIAL COPYRIGHT LICENSE I hereby grant to Simon Fraser University the right to lend my thesis, project or extended essay (the title of which is shown below) to users of the Simon Fraser University Library, and to make partial or sing l e cbp ies only for such users or in response to a reqbest from the library of any other university, or other educational institution, on its own behalf or for one of its users. I further agree that permission for multiple copying of this work for scholarly purposes may be granted by me or the Dean of Graduate Studies. It is understood that copying or publication of this work for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. -

Is Sir Gawain a Typical Knight?

Lesson 3 – Is Sir Gawain a typical knight? Can you use your knowledge of knights to understand Gawain better? Can you demonstrate understanding of knightly principles? Send work to your teacher via Google Classroom, Google Drive or email. Activity 1 Read the following extract taken from the opening of Sir Gawain and the Green Knight. EACH MONTH OF THE YEAR PASSED BY, however, as seasons came and went, it was difficult for Gawain not to think from time to about the terrible fate he must face - sooner now, not later. Many a long night lay awake, willing time to slow but time neither waits nor hurries for any man. It was already Michaelmas (a saint’s day celebrated in September) and he knew he must soon leave and be on his way. His spirits were raised by the love of the king and by his brotherhood of knights. Gawain stayed as long as he could, up until All Saints' Day (a day in November to celebrate all known and unknown saints). The last night before he was to leave they held a great feast in his honour, and everyone at Camelot, lords and ladies, squires and servants, did all they could to keep him merry. But try as they might the jokes and the laughter seemed flat and forced, the smiles thin, for all of them realised this was likely to be the last time they would dine with brave Gawain. No knight in that court was more well-loved and honoured than he. Figure 1 - a medieval feast Bravely, but sadly, Gawain rose to his feet. -

Medieval Beliefs in Arthur's Atlantic Voyages

3 MEDIEVAL BELIEFS IN ARTHUR’S ATLANTIC VOYAGES ARTHUR’S DEATH OVERSEAS IN GEOFFREY’S HISTORY Geoffrey’s Reconcilation of Two Traditions The thesis set out in this book, that Arthur sailed west to a distant land in the sixth century, here identified as North America, is not a new one. It was present at the time that Geoffrey of Monmouth wrote his famous History of the Kings of Britain in c. 1138. Geoffrey drew on a wide range of material to write his book and would have been familiar with the entry in the Annales Cambriae that Arthur died at the battle of Camlann along with Mordred (Medraut) in 537/539. Camlann was thought to be located in Britain. In his pseudo-history, Geoffrey expands this data into a tale of adultery and betrayal. He presents Mordred as Arthur’s nephew, usurping the crown and having a sexual relationship with Guinevere (Gwenhwyfar), while Arthur was fighting in Europe. Hearing this news, Arthur returns to Britain and engages Mordred in a series of battles until Mordred flees to Cornwall. There at the River Camblam (Geoffrey’s location for Camlann) the final battle took place, where Mordred is killed. However at this point Geoffrey inexplicably departs from the basic data of the Annales Cambriae. Instead of Arthur dying at Camlann, Geoffrey presents him as only being severely wounded and abruptly states that he was then carried off to the Isle of Avalon so that his wounds might be healed. No information or explanation concerning the Isle of Avalon is given. The key question of interest is why did not Geoffrey simply allow Arthur’s life to end at Camlann, as in the Annales Cambriae, dying a heroic death but winning the battle against the traitors and heathens opposed to him? The answer to this is that Geoffrey was aware of a different tradition that had Arthur dying at a distant place overseas. -

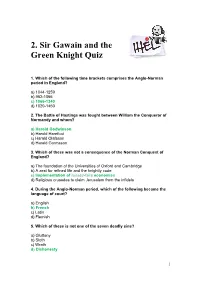

Sir Gawain and the Green Knight Quiz

2. Sir Gawain and the Green Knight Quiz 1. Which of the following time brackets comprises the Anglo-Norman period in England? a) 1044-1259 b) 952-1066 c) 1066-1340 d) 1020-1450 2. The Battle of Hastings was fought between William the Conqueror of Normandy and whom? a) Harold Godwinson b) Harold Harefoot c) Harald Olafsson d) Harald Gormsson 3. Which of these was not a consequence of the Norman Conquest of England? a) The foundation of the Universities of Oxford and Cambridge b) A zest for refined life and the knightly code c) Implementation of laissez-faire economics d) Religious crusades to claim Jerusalem from the infidels 4. During the Anglo-Norman period, which of the following became the language of court? a) English b) French c) Latin d) Flemish 5. Which of these is not one of the seven deadly sins? a) Gluttony b) Sloth c) Wrath d) Dishonesty 1 6. The “Wheel of Fortune” was a pervasive idea throughout the Middle Ages. What did it not represent? a) The ephemeral nature of earthly things b) The stability of all things c) An evolution of the Old English “wyrd” d) That important things in life come from within 7. The Ptolemaic conception of the universe stated what? a) That the earth was located at the centre of the universe b) That the sun was located at the centre of the universe c) That the planets align once every decade d) That the Age of Aquarius would signify the end of the world 8. How many estates was medieval society divided into? a) 2 b) 3 c) 4 d) 5 9. -

The Virgin Mary As the Arms of King Arthur

The Virgin Mary as the Arms of King Arthur C. Baxter∗ www.Colin-Baxter.com © 2019, 2020 Colin Baxter January, 2020 Abstract We present an account of how the Virgin Mary came to have a medieval heraldic association with King Arthur, and suggest a possible reason why the association began in England. Writers on Arthurian heraldry and literature sometime mention that King Arthur used a depiction of the Virgin Mary as his coat-of-arms. Usually little detail is given, other than indicating that the arms are fictitious, and perhaps quoting Nennius, a supposed Welsh monk, as the authority to the claim that Arthur bore the image of the Virgin Mary. The ultimate source of the heraldic association of King Arthur with the Virgin Mary is the Historia Brittonum, which although appearing fanciful at times, is an account of the history of the British Isles from the time of its first settlers up to the Sixth Century. As well as a history, the Historia Brittonum also contains other material such as genealogies and place names. From textual arguments, it is thought to have been written or compiled in Wales, sometime in the Ninth Century by an anonymous author (Fitzpatrick-Mathews, 2015). The attribution of its authorship to a Welsh monk called Nennuis is now discredited. However, the Historia Brittonum is not a Ninth Century document as such, but comprises over forty enigmatic and confusing Latin manuscripts, all of which contain different versions of text. All the extant copies are medieval in origin and therefore date four to five hundred years after the estimated time of an original compilation. -

Sparknotes on Sir Gawain and the Green Knight.” Sparknotes

Sir Gawain and the Green Knight Plot Overview DURING A NEW YEAR’S EVE FEAST at King Arthur’s court, a strange figure, referred to only as the Green Knight, pays the court an unexpected visit. He challenges the group’s leader or any other brave representative to a game. The Green Knight says that he will allow whomever accepts the challenge to strike him with his own axe, on the condition that the challenger find him in exactly one year to receive a blow in return. Stunned, Arthur hesitates to respond, but when the Green Knight mocks Arthur’s silence, the king steps forward to take the challenge. As soon as Arthur grips the Green Knight’s axe, Sir Gawain leaps up and asks to take the challenge himself. He takes hold of the axe and, in one deadly blow, cuts off the knight’s head. To the amazement of the court, the now-headless Green Knight picks up his severed head. Before riding away, the head reiterates the terms of the pact, reminding the young Gawain to seek him in a year and a day at the Green Chapel. After the Green Knight leaves, the company goes back to its festival, but Gawain is uneasy. Time passes, and autumn arrives. On the Day of All Saints, Gawain prepares to leave Camelot and find the Green Knight. He puts on his best armor, mounts his horse, Gringolet, and starts off toward North Wales, traveling through the wilderness of northwest Britain. Gawain encounters all sorts of beasts, suffers from hunger and cold, and grows more desperate as the days pass. -

Romance of the Perilous Land Is a Game Very Much Inspired by the Oldest Fantasy Roleplaying Game Created in the 1970S, but It Is Also Its Own Creation

Sample file SampleScott Malthouse file OSPREY GAMES Bloomsbury Publishing Plc PO Box 883, Oxford, OX1 9PL, UK 1385 Broadway, 5th Floor, New York, NY 10018, USA E-mail: [email protected] www.ospreygames.co.uk OSPREY GAMES is a trademark of Osprey Publishing Ltd First published in Great Britain in 2019 This electronic edition published in 2019 by Bloomsbury Publishing Plc © Scott Malthouse, 2019 Scott Malthouse has asserted his right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988, to be identified as Author of this work. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publishers. A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. ISBN: HB 9781472834775; eBook 9781472834782; ePDF 9781472834751; XML 9781472834768 Osprey Games supports the Woodland Trust, the UK’s leading woodland conservation charity. To find out more about our authors and books visit www.ospreypublishing.com. Here you will find extracts, author interviews, details of forthcoming events and the option to sign up for our newsletter. SampleArtwork: John McCambridge, Alan Lathwell, and David Needham file ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I’d like to thank Natalie for putting up with me while I wrote this. I’d also like to thank Steve, Pete, Dave, McB, and Neil for helping me bring this to life. Finally I want to thank Ken St. Andre for putting me on -

Urban Spaces Sir Gawain and the Green Knight

URBAN SPACES SIR GAWAIN AND THE GREEN KNIGHT This is a story written almost 700 years ago. It comes from north-west England. The story is a Christian version of a Green Man myth, set in the time of King Arthur and the Knights of the Round Table. The Green Knight seems at first to be a wild man but he tests Sir Gawain's courage and honesty. King Arthur, his knights and the ladies of the court were celebrating the Christmas festival at Camelot. On New Year’s Eve they were all seated in the hall, feasting and making merry. Only the King was not eating, for he had vowed not to eat until someone told an adventurous tale. It was an icy night, and the snow lay thick outside the castle. Suddenly the great doors were flung open and a rush of freezing air swept into the hall. In rode a horse with a gigantic, fierce knight on its back. The knight was dressed all in green, his face, beard and hair were green - and so was his horse. In one hand the knight held a large green axe, and in the other he carried a holly bush. ‘Who is the leader among you?’ asked the Green Knight in a booming voice. ‘I am the Lord of Camelot. You are welcome to join our celebrations,’ answered King Arthur. He hoped this strange knight would have some wondrous tales to tell. But the knight did not dismount from his horse. Sitting high in his saddle he said: ‘I offer a challenge. -

When a Knight Meets a Dragon Maiden: Human Identity and the Monstrous Animal Other

When a Knight meets a Dragon Maiden: Human Identity and the Monstrous Animal Other (Detail of ‘Mélusine in the Bath’, illustration to Thüring von Ringoltingen’s Mélusine, 14771) Research Master Thesis Name: Lydia Zeldenrust Student Number: 3440346 Date: 11 July 2011 Supervisor: dr. Katell Lavéant Second Reader: dr. Jelle Koopmans 1 Taken from Françoise Clier-Colombani, La Fée Mélusine au Moyen Age: Images, Mythes et Symboles (Paris: Le Léopard d’Or, 1991), front page and image 15 of the appendix. Acknowledgements I would like to thank several people who have all played a different part in my process of writing this Thesis. Firstly, of course, I would like to thank my supervisor, dr. Katell Lavéant, for all she has done. I would like to express my gratitude and admiration for her daring to take on this topic with me, for her useful feedback, and for all the time she has bestowed upon me. I would naturally also like to thank the second reader, dr. Jelle Koopmans, for being so kind to take on the task. Secondly, I wish to thank dr. Bart Besamusca, not only for being my tutor, but also for being a constant source of support over the past two years. I am happy that he is always willing to listen to my passionate, though perhaps at times somewhat strange, plans and ideas. Finally, I would like to thank several people from outside Utrecht University; dr. Karen Olsen, prof. Simon Gaunt, prof. Karen Pratt, and dr. Sarah Salih, for having helped me with several queries into the world of (medieval) academia, and for allowing me to sit in on their wonderful classes.