“Evil Isn't Born, It's Made”: As Communicated in Once Upon a Time

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Grade 6 Reading Student At–Home Activity Packet

Printer Warning: This packet is lengthy. Determine whether you want to print both sections, or only print Section 1 or 2. Grade 6 Reading Student At–Home Activity Packet This At–Home Activity packet includes two parts, Section 1 and Section 2, each with approximately 10 lessons in it. We recommend that your student complete one lesson each day. Most lessons can be completed independently. However, there are some lessons that would benefit from the support of an adult. If there is not an adult available to help, don’t worry! Just skip those lessons. Encourage your student to just do the best they can with this content—the most important thing is that they continue to work on their reading! Flip to see the Grade 6 Reading activities included in this packet! © 2020 Curriculum Associates, LLC. All rights reserved. Section 1 Table of Contents Grade 6 Reading Activities in Section 1 Lesson Resource Instructions Answer Key Page 1 Grade 6 Ready • Read the Guided Practice: Answers will vary. 10–11 Language Handbook, Introduction. Sample answers: Lesson 9 • Complete the 1. Wouldn’t it be fun to learn about Varying Sentence Guided Practice. insect colonies? Patterns • Complete the 2. When I looked at the museum map, Independent I noticed a new insect exhibit. Lesson 9 Varying Sentence Patterns Introduction Good writers use a variety of sentence types. They mix short and long sentences, and they find different ways to start sentences. Here are ways to improve your writing: Practice. Use different sentence types: statements, questions, imperatives, and exclamations. Use different sentence structures: simple, compound, complex, and compound-complex. -

L'équipe Des Scénaristes De Lost Comme Un Auteur Pluriel Ou Quelques Propositions Méthodologiques Pour Analyser L'auctorialité Des Séries Télévisées

Lost in serial television authorship : l’équipe des scénaristes de Lost comme un auteur pluriel ou quelques propositions méthodologiques pour analyser l’auctorialité des séries télévisées Quentin Fischer To cite this version: Quentin Fischer. Lost in serial television authorship : l’équipe des scénaristes de Lost comme un auteur pluriel ou quelques propositions méthodologiques pour analyser l’auctorialité des séries télévisées. Sciences de l’Homme et Société. 2017. dumas-02368575 HAL Id: dumas-02368575 https://dumas.ccsd.cnrs.fr/dumas-02368575 Submitted on 18 Nov 2019 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Distributed under a Creative Commons Attribution - NonCommercial - NoDerivatives| 4.0 International License UNIVERSITÉ RENNES 2 Master Recherche ELECTRA – CELLAM Lost in serial television authorship : L'équipe des scénaristes de Lost comme un auteur pluriel ou quelques propositions méthodologiques pour analyser l'auctorialité des séries télévisées Mémoire de Recherche Discipline : Littératures comparées Présenté et soutenu par Quentin FISCHER en septembre 2017 Directeurs de recherche : Jean Cléder et Charline Pluvinet 1 « Créer une série, c'est d'abord imaginer son histoire, se réunir avec des auteurs, la coucher sur le papier. Puis accepter de lâcher prise, de la laisser vivre une deuxième vie. -

A Foucauldian Analysis of Black Swan

Introduction In the 2010 movie Black Swan , Nina Sayers is filmed repeatedly practicing a specific ballet turn after her teacher mentioned her need for improvement earlier that day. Played by Natalie Portman, Nina is shown spinning in her room at home, sweating with desperation and determination trying to execute the turn perfectly. Despite the hours of gruesome rehearsal, Nina must nail every single aspect of this particular turn to fully embody the role she is cast in. After several attempts at the move, she falls, exhausted, clutching her newly twisted ankle in agony. Perfection, as shown in this case, runs hand in hand with pain. Crying to herself, Nina holds her freshly hurt ankle and contemplates how far she will go to mold her flesh into the perfectly obedient body. This is just one example in the movie Black Swan in which the main character Nina, chases perfection. Based on the demanding world of ballet, Darren Aronofsky creates a new-age portrayal of the life of a young ballet dancer, faced with the harsh obstacles of stardom. Labeled as a “psychological thriller” and horror film, Black Swan tries to capture Nina’s journey in becoming the lead of the ever-popular “Swan Lake.” However, being that the movie is set in modern times, the show is not about your usual ballet. Expecting the predictable “Black Swan” plot, the ballet attendees are thrown off by the twists and turns created by this mental version of the show they thought they knew. Similarly, the attendees for the movie Black Swan were surprised at the risks Aronofsky took to create this haunting masterpiece. -

Storybrooke, Maine, Is Home to “All the Classic Characters We Know

Storybrooke, maine, is home to “all the classic characters we know. or think we know.” 4 0 p o r t l a n d monthly magazine Maine Mystique our state stars in the tV series Once Upon a Time. interview by colin w. Sargent dward Kitsis and Adam Horowitz, creators of the hit [ABC, Sundays at 8 p.m.], give their take on what’s so Emythic about where we live and why we’ve been chosen for this metafictional honor. The duo first won acclaim as writ- ers of Lost [2004-2010]. They met as stu- dents at U-Wis consin-Madison. Has either of you been to Maine before? AdAm Horowitz: Yes, but I was so young I don’t really remember it. I grew up in New York, and my visit had to do with coming up during the summer, driving up the East Coast with my family. All these years later, working on this series, we found Maine an easy choice. We thought, it’s such a cool place to drop these charac- ters into. It’s kind of isolated. Stephen King has made it mythic. Whose creative inspiration was it to set Sto- rybrooke in Maine? photo K EdwArd Kitsis: It was a decision both of toc S ; i us made. HILL There must have been a second-place finisher HAREN /K for ‘most horrible place in the world.’ ABC EK: I think we would have gone with Oregon or Washington, but we loved from top: file; the feeling of Maine. We wanted that D e c e m b e r 2 0 1 1 4 1 Maine Mystique CELEBRATE SEASON the WITH MAINE HISTORICAL SOCIETY kind of Stephen King vibe–my favorite NOVEMBER 19 – DECEMBER 31, 2011 book of his is actually his nonfiction book, On Writing. -

BROKEN PROMISES: Continuing Federal Funding Shortfall for Native Americans

U.S. COMMISSION ON CIVIL RIGHTS BROKEN PROMISES: Continuing Federal Funding Shortfall for Native Americans BRIEFING REPORT U.S. COMMISSION ON CIVIL RIGHTS Washington, DC 20425 Official Business DECEMBER 2018 Penalty for Private Use $300 Visit us on the Web: www.usccr.gov U.S. COMMISSION ON CIVIL RIGHTS MEMBERS OF THE COMMISSION The U.S. Commission on Civil Rights is an independent, Catherine E. Lhamon, Chairperson bipartisan agency established by Congress in 1957. It is Patricia Timmons-Goodson, Vice Chairperson directed to: Debo P. Adegbile Gail L. Heriot • Investigate complaints alleging that citizens are Peter N. Kirsanow being deprived of their right to vote by reason of their David Kladney race, color, religion, sex, age, disability, or national Karen Narasaki origin, or by reason of fraudulent practices. Michael Yaki • Study and collect information relating to discrimination or a denial of equal protection of the laws under the Constitution Mauro Morales, Staff Director because of race, color, religion, sex, age, disability, or national origin, or in the administration of justice. • Appraise federal laws and policies with respect to U.S. Commission on Civil Rights discrimination or denial of equal protection of the laws 1331 Pennsylvania Avenue, NW because of race, color, religion, sex, age, disability, or Washington, DC 20425 national origin, or in the administration of justice. (202) 376-8128 voice • Serve as a national clearinghouse for information TTY Relay: 711 in respect to discrimination or denial of equal protection of the laws because of race, color, www.usccr.gov religion, sex, age, disability, or national origin. • Submit reports, findings, and recommendations to the President and Congress. -

ALLISA SWANSON Costume Designer

ALLISA SWANSON Costume Designer https://www.allisaswanson.com/ Selected Television: FIREFLY LANE (Pilot, S1&2) – Netflix / Brightlight Pictures – Maggie Friedman, creator TURNER & HOOCH (Pilot, S1) – 20th Century Fox / Disney+ – Matt Nix, writer – McG, pilot dir. ALIVE (Pilot) – CBS Studios – Uta Briesewitz, director ANOTHER LIFE (Pilot, S1) – Netflix / Halfire Entertainment – Aaron Martin, creator ONCE UPON A TIME (S7 eps. 716-722) – Disney/ABC TV – Edward Kitsis & Adam Horowitz, creators *NOMINATED, Excellence in Costume Design in TV – Sci-Fi/Fantasy - CAFTCAD Awards THE 100 (S3 + S4) – Alloy Entertainment / Warner Bros. / The CW – Jason Rothenberg, creator DEAD OF SUMMER (Pilot, S1) Disney / ABC / Freeform – Ian Goldberg, Adam Horowitz & Eddy Kitsis, creators MORTAL KOMBAT: LEGACY (Mini Series) – Warner Bros. – Kevin Tancharoen, director BEYOND SHERWOOD (TV Movie) – SyFy / Starz – Peter DeLuise, director KNIGHTS OF BLOODSTEEL (Mini-Series) – SyFy / Reunion Pictures – Phillip Spink, director SEA BEAST (TV Movie) – SyFy / NBC Universal TV – Paul Ziller, director EDGEMONT (S1 - S5) – CBC / Water Street Pictures / Fox Family Channel – Ian Weir, creator Selected Features: COFFEE & KAREEM – Netflix / Pacific Electric Picture Company – Michael Dowse, director GOOD BOYS (Addt’l Photo. )– Universal / Good Universe / Point Grey Pictures – Gene Stupnitsky, dir. DARC – Netflix / JRN Productions – Nick Powell, director THE UNSPOKEN – Lighthouse Pictures / Paladin – Sheldon Wilson, director THE MARINE: HOMEFRONT – WWE Studios – Scott Wiper, director ICARUS/THE KILLING MACHINE – Cinetel Films – Dolph Lundgren, director SPACE BUDDIES – Walt Disney Home Entertainment – Robert Vince, director DANCING TREES – NGN Productions – Anne Wheeler, director THE BETRAYED – MGM – Amanda Gusack, director SNOW BUDDIES – Walt Disney Home Entertainment – Robert Vince, director BLONDE & BLONDER – Rigel Entertainment – Bob Clark, director CHESTNUT: HERO OF CENTRAL PARK – Miramax / Keystone Entertainment – Robert Vince, dir. -

Foot Pedestal Brooke Mckenzie Sroufe

Shattered Moments: The Fall from My 30-Foot Pedestal Brooke McKenzie Sroufe Faculty Advisor: Margaret Sartor Graduate Liberal Studies April 2015 This project was submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Graduate Liberal Studies in the Graduate School of Duke University. Copyright by Brooke McKenzie Sroufe 2015 Abstract Part One of my final project consists of a series of creative non-fiction stories detailing a traumatic accident I experienced in 2009. The stories examine my physical and emotional recovery. I have also written stories about my strongest childhood memories to explore the events that helped shape the beliefs I held at the time of my accident. The stories are not linear, but span from my childhood to the three years following my accident. Through these stories, I hope to contribute to greater conversations about trauma, emerging adulthood, and identity— particularly among young people. Part Two of the project analyzes the question of trauma and the necessity of narrative following trauma. I break this section of the project into three short essays addressing different aspects of trauma and narrative: a history of trauma, the need for memoir, and posttraumatic growth. I reference three larger works within these essays and relate the authors’ arguments and theories to my traumatic experience and to the process of writing my stories. In addition to these written parts, I include personal photographs throughout the project. These pictures, like my stories, are not linear. They are visual pieces of my shattered life puzzle, showing me before and after my fall from the 30-foot pedestal I’d created for myself. -

Tracing Fairy Tales in Popular Culture Through the Depiction of Maternity in Three “Snow White” Variants

University of Louisville ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository College of Arts & Sciences Senior Honors Theses College of Arts & Sciences 5-2014 Reflective tales : tracing fairy tales in popular culture through the depiction of maternity in three “Snow White” variants. Alexandra O'Keefe University of Louisville Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.louisville.edu/honors Part of the Children's and Young Adult Literature Commons, and the Comparative Literature Commons Recommended Citation O'Keefe, Alexandra, "Reflective tales : tracing fairy tales in popular culture through the depiction of maternity in three “Snow White” variants." (2014). College of Arts & Sciences Senior Honors Theses. Paper 62. http://doi.org/10.18297/honors/62 This Senior Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Arts & Sciences at ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in College of Arts & Sciences Senior Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. This title appears here courtesy of the author, who has retained all other copyrights. For more information, please contact [email protected]. O’Keefe 1 Reflective Tales: Tracing Fairy Tales in Popular Culture through the Depiction of Maternity in Three “Snow White” Variants By Alexandra O’Keefe Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for Graduation summa cum laude University of Louisville March, 2014 O’Keefe 2 The ability to adapt to the culture they occupy as well as the two-dimensionality of literary fairy tales allows them to relate to readers on a more meaningful level. -

Snow White: Evil Witches Professor Joanna Bourke 19 November 2020

Snow White: Evil Witches Professor Joanna Bourke 19 November 2020 Each generation invents evil. And evil women have incited our imaginations since Eve first plucked that apple. One of my favourites evil women is the Evil Queen in the story of Snow White. She is the archetypical ageing woman: post-menopausal and demonised as the ugly hag, malicious crone, and depraved witch. She is evil, obscene, and threatening because of her familiarity with the black arts, her skills in mixing poisonous potions, and her possession of a magic mirror. She is also sexual and aware: like Eve, she has tasted of the Tree of Knowledge. Her story first roused the imaginations of the Brothers Grimm in 1812 and 1819: the second version stripped the story of its ribald connotations while retaining (and even augmenting) its sadism. Famously, “Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs” was set to song by Disney in 1937, a film that is often hailed as the “seminal” version. Interestingly, the word “seminal” itself comes from semen, so is encoded male. Its exploitation by Disney has helped the company generate over $48 billion dollars a year through its movies, theme parks, and memorabilia such as collectible cards, colouring-in books, “princess” gowns and tiaras, dolls, peaked hats, and mirrors. Snow White and the Evil Queen appears in literature, music, dance, theatre, fine arts, television, comics, and the internet. It remains a powerful way to castigate powerful women – as during Hillary Clinton’s bid for the White House, when she was regularly dubbed the Witch. This link between powerful women and evil witchery has made the story popular amongst feminist storytellers, keen to show how the story shapes the way children and adults think about gender and sexuality, race and class. -

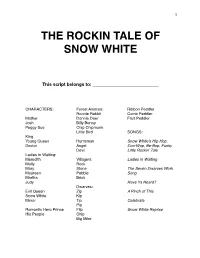

Rockin Snow White Script

!1 THE ROCKIN TALE OF SNOW WHITE This script belongs to: __________________________ CHARACTERS: Forest Animals: Ribbon Peddler Roonie Rabbit Comb Peddler Mother Donnie Deer Fruit Peddler Josh Billy Bunny Peggy Sue Chip Chipmunk Little Bird SONGS: King Young Queen Huntsman Snow White’s Hip-Hop, Doctor Angel Doo-Wop, Be-Bop, Funky Devil Little Rockin’ Tale Ladies in Waiting: Meredith Villagers: Ladies in Waiting Molly Rock Mary Stone The Seven Dwarves Work Maureen Pebble Song Martha Brick Judy Have Ya Heard? Dwarves: Evil Queen Zip A Pinch of This Snow White Kip Mirror Tip Celebrate Pip Romantic Hero Prince Flip Snow White Reprise His People Chip Big Mike !2 SONG: SNOW WHITE HIP-HOP, DOO WOP, BE-BOP, FUNKY LITTLE ROCKIN’ TALE ALL: Once upon a time in a legendary kingdom, Lived a royal princess, fairest in the land. She would meet a prince. They’d fall in love and then some. Such a noble story told for your delight. ’Tis a little rockin’ tale of pure Snow White! They start rockin’ We got a tale, a magical, marvelous, song-filled serenade. We got a tale, a fun-packed escapade. Yes, we’re gonna wail, singin’ and a-shoutin’ and a-dancin’ till my feet both fail! Yes, it’s Snow White’s hip-hop, doo-wop, be-bop, funky little rockin’ tale! GIRLS: We got a prince, a muscle-bound, handsome, buff and studly macho guy! GUYS: We got a girl, a sugar and spice and-a everything nice, little cutie pie. ALL: We got a queen, an evil-eyed, funkified, lean and mean, total wicked machine. -

1 for IMMEDIATE RELEASE: January 27, 2017 BC's Leo Awards Makes a Historic Move in Canada's Film & TV Industry for Acce

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE: January 27, 2017 BC’s Leo Awards Makes a Historic Move in Canada’s Film & TV Industry for Accepting Gender-Fluid Performer in Both Male and Female Performance Categories Star of short film Limina gender-fluid eleven-year old Vancouver actor Ameko Eks Mass Carroll is being submitted into both Male and Female Performance categories for the Leo Awards. In a historic move, The Leo Awards, a Project of the Motion Pictures of Arts and Sciences Foundation of British Columbia, has set a precedent in the Canadian Film and Television industry by accepting a gender-fluid performer’s request to be submitted into both Male and Female performance categories. "We are proud to join our colleagues at the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences in recognizing the importance of inclusivity when honouring artistic excellence" says Walter Daroshin, Chair of the Motion Picture Arts & Sciences Foundation of British Columbia and President of the Leo Awards.” Ameko Eks Mass Carroll, an eleven year-old Vancouver performer, stars in the short film entitled Limina, directed and produced by Vancouver-based filmmakers Florian Halbedl and Joshua M. Ferguson. Ameko plays gender- fluid protagonist, Alessandra, in Limina and also identifies as gender-fluid and uses he/him/his pronouns. Ameko identifies as a boy and other days as a girl and some days as neither. The filmmakers have submitted Ameko’s performance into both Male and Female Performance categories for the Leo Awards. Ameko says, “I would love to give the Leo Awards a ginormous thanks for making people under the trans umbrella feel more welcomed in the world. -

Of Books the Once Upon a Time, and What Happened Next

£2.00 Oxonianthe Review hilary 2005 . volume 4 . issue 2 of books Márquez’s sad whores: Glen Goodman Joseph Nye on playing the power game When things go wrong in Libya: John Bohannon Th e miseducation of Tom Wolfe: Jenni Quilter Marjane Satrapi’s alternative Iran: Kristin Anderson Th e life and times of Glenn Gould: Ditlev Rindom Once upon a time, and what happened next ... by Philip Pullman 2 the Oxonian Review of books hilary 2005 . volume 4 . issue 2 In this Issue: From the Editor Features n 1951, Th eodor Adorno claimed that ‘cultural criti- ing: standing up against McCarthyism and the House Talking power cism exists in confrontation with the fi nal level of the Un-American Activities Committee, campaigning for Tim Soutphommasane and Shaun Chau interview I Joseph Nye page 4 dialectic of culture and barbarism: to write a poem after the freedom of dissident writers, especially in the former Auschwitz is barbaric, and that also gnaws at the knowl- USSR, and protesting against all forms of censorship. Once upon a time, and what happened next ... edge which states why it has become impossible to write Most recently, he publicly criticised the invasion of Iraq Philip Pullman page 10 poems today’. Th is statement, often reduced to the axiom and subsequent abridgements of civil liberties. ‘to write a poem after Auschwitz is barbaric’, remains ‘Forty years after the Holocaust, I can speak about Oxford Authors in Print to this day one of the most provocative challenges not Memory, but not about Versöhnung, or reconciliation’, The latest publications from Oxford-based authors page 19 just for poets (as well as writers, journalists, cultural and wrote Eli Wiesel, one of the foremost writers on the political critics, philosophers, and world leaders), but also Holocaust.