Snow White in the Spanish Cultural Tradition

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fairy Tale Females: What Three Disney Classics Tell Us About Women

FFAAIIRRYY TTAALLEE FFEEMMAALLEESS:: WHAT THREE DISNEY CLASSICS TELL US ABOUT WOMEN Spring 2002 Debbie Mead http://members.aol.com/_ht_a/ vltdisney?snow.html?mtbrand =AOL_US www.kstrom.net/isk/poca/pocahont .html www_unix.oit.umass.edu/~juls tar/Cinderella/disney.html Spring 2002 HCOM 475 CAPSTONE Instructor: Dr. Paul Fotsch Advisor: Professor Frances Payne Adler FAIRY TALE FEMALES: WHAT THREE DISNEY CLASSICS TELL US ABOUT WOMEN Debbie Mead DEDICATION To: Joel, whose arrival made the need for critical viewing of media products more crucial, Oliver, who reminded me to be ever vigilant when, after viewing a classic Christmas video from my youth, said, “Way to show me stereotypes, Mom!” Larry, who is not a Prince, but is better—a Partner. Thank you for your support, tolerance, and love. TABLE OF CONTENTS Once Upon a Time --------------------------------------------1 The Origin of Fairy Tales ---------------------------------------1 Fairy Tale/Legend versus Disney Story SNOW WHITE ---------------------------------------------2 CINDERELLA ----------------------------------------------5 POCAHONTAS -------------------------------------------6 Film Release Dates and Analysis of Historical Influence Snow White ----------------------------------------------8 Cinderella -----------------------------------------------9 Pocahontas --------------------------------------------12 Messages Beauty --------------------------------------------------13 Relationships with other women ----------------------19 Relationships with men --------------------------------21 -

Snow White & Rose

Penguin Young Readers Factsheets Level 2 Snow White Teacher’s Notes and Rose Red Summary of the story Snow White and Rose Red is the story of two sisters who live with their mother in the forest. One cold winter day a bear comes to their house to shelter, and they give him food and drink. Later, in the spring, the girls are in the forest, and they see a dwarf whose beard is stuck under a tree. The girls cut his beard to free him, but he is not grateful. Some days after, they see the dwarf attacked by a large bird and again rescue him. Next, they see the dwarf with treasure. He tells the bear that they are thieves. The bear recognizes the sisters and scares the dwarf away. After hugging the sisters, he turns into a prince. The girls go to his castle, marry the prince and his brother and their mother joins them. About the author The story was first written down by Charles Perrault in the mid seventeenth century. Then it was popularized by the Grimm brothers, Jacob Ludwig Karl Grimm, 1785-1863, and Wilhelm Karl Grimm, 1786-1859. They were both professors of German literature and librarians at the University of Gottingen who collected and wrote folk tales. Topics and themes Animals. How big are bears? How strong are they? Encourage the pupils to research different types of bears. Look at their habitat, eating habits, lives. Collect pictures of them. Fairy tales. Several aspects from this story could be taken up. Feelings. The characters in the story go through several emotions: fear, (pages 1,10) anger, (page 5) surprise (page 11). -

Tracing Fairy Tales in Popular Culture Through the Depiction of Maternity in Three “Snow White” Variants

University of Louisville ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository College of Arts & Sciences Senior Honors Theses College of Arts & Sciences 5-2014 Reflective tales : tracing fairy tales in popular culture through the depiction of maternity in three “Snow White” variants. Alexandra O'Keefe University of Louisville Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.louisville.edu/honors Part of the Children's and Young Adult Literature Commons, and the Comparative Literature Commons Recommended Citation O'Keefe, Alexandra, "Reflective tales : tracing fairy tales in popular culture through the depiction of maternity in three “Snow White” variants." (2014). College of Arts & Sciences Senior Honors Theses. Paper 62. http://doi.org/10.18297/honors/62 This Senior Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Arts & Sciences at ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in College of Arts & Sciences Senior Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. This title appears here courtesy of the author, who has retained all other copyrights. For more information, please contact [email protected]. O’Keefe 1 Reflective Tales: Tracing Fairy Tales in Popular Culture through the Depiction of Maternity in Three “Snow White” Variants By Alexandra O’Keefe Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for Graduation summa cum laude University of Louisville March, 2014 O’Keefe 2 The ability to adapt to the culture they occupy as well as the two-dimensionality of literary fairy tales allows them to relate to readers on a more meaningful level. -

Siemens Technology at the New Seven Dwarfs Mine Train

Siemens Technology at the new Seven Dwarfs Mine Train Lake Buena Vista, FL – Since 1937, Snow White and Seven Dwarfs have been entertaining audiences of all ages. As of May 28, 2014, the story found a new home within the largest expansion at the Magic Kingdom® Park. The Seven Dwarfs Mine Train, along with a host of new attractions, shows and restaurants now call New Fantasyland home. The Seven Dwarfs Mine Train, an exciting family coaster, features a forty-foot drop and a series of curves that send guests seated in mine cars swinging and swaying through the hills and caves of the enchanted forest. As part of the systems used to manage the operation of this new attraction, Walt Disney Imagineering chose Siemens to help automate many of the attraction‟s applications. Thanks to Siemens innovations, Sleepy, Doc, Grumpy, Bashful, Sneezy, Happy and Dopey entertain the guests while Siemens technologies are hard at work throughout the infrastructure of the attraction. This includes a host of Siemens‟ systems to ensure that the attraction runs safely and smoothly so that the mine cars are always a required distance from each other. Siemens equipment also delivers real-time information to the Cast Members operating the attraction for enhanced safety, efficiency and communication. The same Safety Controllers, SINAMICS safety variable frequency drives and Scalance Ethernet switches are also found throughout other areas of the new Fantasyland such as the new Dumbo the Flying Elephant®, and Under the Sea – Journey of the Little Mermaid attractions. And Siemens Fire and Safety technologies are found throughout Cinderella Castle. -

Snow White’’ Tells How a Parent—The Queen—Gets Destroyed by Jealousy of Her Child Who, in Growing Up, Surpasses Her

WARNING Concerning Copyright Restrictions The copyright law of the United States (Title 1.7, United States Code) governs the making of photocopies or other reproductions of copyrighted material. Under certain conditions specified in the law, libraries and archives are authorized to furnish a photocopy or reproduction. One of three specified conditions is that the photocopy or reproduction is not to be used for any purpose other than private study, scholarship or research. If electronic transmission of reserve material is used for purposes in excess of what constitutes “fair use”, that user may be liable for copyright infringement. This policy is in effect for the following document: Fear of Fantasy 117 people. They do not realize that fairy tales do not try to describe the external world and “reality.” Nor do they recognize that no sane child ever believes that these tales describe the world realistically. Some parents fear that by telling their children about the fantastic events found in fairy tales, they are “lying” to them. Their concern is fed by the child’s asking, “Is it true?” Many fairy tales offer an answer even before the question can be asked—namely, at the very beginning of the story. For example, “Ali Baba and the Forty Thieves” starts: “In days of yore and times and tides long gone. .” The Brothers Grimm’s story “The Frog King, or Iron Henry” opens: “In olden times when wishing still helped one. .” Such beginnings make it amply clear that the stories take place on a very different level from everyday “reality.” Some fairy tales do begin quite realistically: “There once was a man and a woman who had long in vain wished for a child.” But the child who is familiar with fairy stories always extends the times of yore in his mind to mean the same as “In fantasy land . -

Snow White: Evil Witches Professor Joanna Bourke 19 November 2020

Snow White: Evil Witches Professor Joanna Bourke 19 November 2020 Each generation invents evil. And evil women have incited our imaginations since Eve first plucked that apple. One of my favourites evil women is the Evil Queen in the story of Snow White. She is the archetypical ageing woman: post-menopausal and demonised as the ugly hag, malicious crone, and depraved witch. She is evil, obscene, and threatening because of her familiarity with the black arts, her skills in mixing poisonous potions, and her possession of a magic mirror. She is also sexual and aware: like Eve, she has tasted of the Tree of Knowledge. Her story first roused the imaginations of the Brothers Grimm in 1812 and 1819: the second version stripped the story of its ribald connotations while retaining (and even augmenting) its sadism. Famously, “Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs” was set to song by Disney in 1937, a film that is often hailed as the “seminal” version. Interestingly, the word “seminal” itself comes from semen, so is encoded male. Its exploitation by Disney has helped the company generate over $48 billion dollars a year through its movies, theme parks, and memorabilia such as collectible cards, colouring-in books, “princess” gowns and tiaras, dolls, peaked hats, and mirrors. Snow White and the Evil Queen appears in literature, music, dance, theatre, fine arts, television, comics, and the internet. It remains a powerful way to castigate powerful women – as during Hillary Clinton’s bid for the White House, when she was regularly dubbed the Witch. This link between powerful women and evil witchery has made the story popular amongst feminist storytellers, keen to show how the story shapes the way children and adults think about gender and sexuality, race and class. -

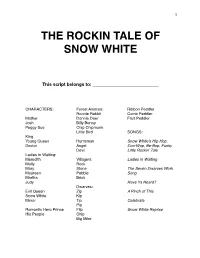

Rockin Snow White Script

!1 THE ROCKIN TALE OF SNOW WHITE This script belongs to: __________________________ CHARACTERS: Forest Animals: Ribbon Peddler Roonie Rabbit Comb Peddler Mother Donnie Deer Fruit Peddler Josh Billy Bunny Peggy Sue Chip Chipmunk Little Bird SONGS: King Young Queen Huntsman Snow White’s Hip-Hop, Doctor Angel Doo-Wop, Be-Bop, Funky Devil Little Rockin’ Tale Ladies in Waiting: Meredith Villagers: Ladies in Waiting Molly Rock Mary Stone The Seven Dwarves Work Maureen Pebble Song Martha Brick Judy Have Ya Heard? Dwarves: Evil Queen Zip A Pinch of This Snow White Kip Mirror Tip Celebrate Pip Romantic Hero Prince Flip Snow White Reprise His People Chip Big Mike !2 SONG: SNOW WHITE HIP-HOP, DOO WOP, BE-BOP, FUNKY LITTLE ROCKIN’ TALE ALL: Once upon a time in a legendary kingdom, Lived a royal princess, fairest in the land. She would meet a prince. They’d fall in love and then some. Such a noble story told for your delight. ’Tis a little rockin’ tale of pure Snow White! They start rockin’ We got a tale, a magical, marvelous, song-filled serenade. We got a tale, a fun-packed escapade. Yes, we’re gonna wail, singin’ and a-shoutin’ and a-dancin’ till my feet both fail! Yes, it’s Snow White’s hip-hop, doo-wop, be-bop, funky little rockin’ tale! GIRLS: We got a prince, a muscle-bound, handsome, buff and studly macho guy! GUYS: We got a girl, a sugar and spice and-a everything nice, little cutie pie. ALL: We got a queen, an evil-eyed, funkified, lean and mean, total wicked machine. -

A Critical Reading of Age and Aging in Snow White and the Huntsman and Mirror Mirror

Of Young/Old Queens and Giant Dwarfs: A Critical Reading of Age and Aging in Snow White and the Huntsman and Mirror Mirror Anita Wohlmann This article1 draws on the curious coincidence of several film releases of the “Snow White” tale in 2012. The Internet Movie Database lists five films with direct references to the fairy tale, among them Snow White and the Huntsman (directed by Rupert Sanders, starring Charlize Theron and Kristen Stewart) and Mirror Mirror (directed by Tarsem Singh, starring Julia Roberts and Lily Collins).2 According to Jack Zipes, who collected thirty-five cinematographic representations of “Snow White” in The Enchanted Screen (2011), there is a “profound widespread public inter- est in a tale [i.e., “Snow White”] that provokes retelling and reflection because it touches upon deeply rooted problems in every culture of the world ranging from what constitutes our notions of beauty to what causes conflicts between women, especially mothers and daughters and stepmothers and daughters” (119). Which “deeply rooted problem” has inspired this recent revival of “Snow White”? Why do we keep retelling this particular fairy tale?3 Maria Tatar suggests that it is the topic of aging that preoccupies contemporary directors, screenwriters, and audiences: “It may be that there is something about the boomer anxiety about aging that is renewing our interest in Snow White” (Ulaby). In The New Yorker, she adds that Snow White and the Huntsman “captures a deepening anxiety about aging and generational sexual rivalry” (Tatar). The rivalry between mothers and daughters has been a central issue in Second Wave feminist criticism (see, e.g., Barzilai; Gilbert and Gubar). -

Characters' Actions and Reactions

Dear Family Member, Welcome to our next unit of study, “Characters’ Actions and Reactions.” We are beginning our second unit of study in the Benchmark Advance program. As a reminder, each three-week unit features one topic. As with the previous unit, I am providing suggested activities you and your child can do together at home to build on the work we’re doing in class. In our second unit of study, “Characters’ Actions and Reactions,” your child will explore how characters drive the action of a plot. For example, in the fairy tale “Snow White Meets the Huntsman,” students discover the lengths that the queen is willing to go to destroy Snow White, all due to her envy and vanity. Your child will also explore some of the morals and messages in Aesop’s Fables, where are character-driven stories meant to teach children centuries ago how to behave and lead their own lives. his will help students begin thinking about how they come across as characters in their own lives, with actions and reactions similar to those of characters they read about. he selections include a variety of genres, including fables, fairy tales, fantasy, animal fantasy, and informational texts. I’m looking forward to this exciting unit, exploring with your children the wide range of characters we encounter in literature. It will be fun to discover how the children connect with the various characters as well as recognize the historical signifcance of some of our favorite children’s tales. As always, should you have any questions about our reading program or about your child’s progress, please don’t hesitate to contact me. -

Gender and Fairy Tales

Issue 2013 44 Gender and Fairy Tales Edited by Prof. Dr. Beate Neumeier ISSN 1613-1878 About Editor Prof. Dr. Beate Neumeier Gender forum is an online, peer reviewed academic University of Cologne journal dedicated to the discussion of gender issues. As English Department an electronic journal, gender forum offers a free-of- Albertus-Magnus-Platz charge platform for the discussion of gender-related D-50923 Köln/Cologne topics in the fields of literary and cultural production, Germany media and the arts as well as politics, the natural sciences, medicine, the law, religion and philosophy. Tel +49-(0)221-470 2284 Inaugurated by Prof. Dr. Beate Neumeier in 2002, the Fax +49-(0)221-470 6725 quarterly issues of the journal have focused on a email: [email protected] multitude of questions from different theoretical perspectives of feminist criticism, queer theory, and masculinity studies. gender forum also includes reviews Editorial Office and occasionally interviews, fictional pieces and poetry Laura-Marie Schnitzler, MA with a gender studies angle. Sarah Youssef, MA Christian Zeitz (General Assistant, Reviews) Opinions expressed in articles published in gender forum are those of individual authors and not necessarily Tel.: +49-(0)221-470 3030/3035 endorsed by the editors of gender forum. email: [email protected] Submissions Editorial Board Target articles should conform to current MLA Style (8th Prof. Dr. Mita Banerjee, edition) and should be between 5,000 and 8,000 words in Johannes Gutenberg University Mainz (Germany) length. Please make sure to number your paragraphs Prof. Dr. Nilufer E. Bharucha, and include a bio-blurb and an abstract of roughly 300 University of Mumbai (India) words. -

Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs 10.11.82 Scene 1

SNOW WHITE AND THE SEVEN DWARFS 10.11.82 SCENE 1 : In the palace (lights on to WickeD Queen holDing mirror up anD gazing into it) WICKED QUEEN: (to mirror) Mirror, mirror in my hanD, Who’s the fairiest in the lanD……? MIRROR (VOICE): Queen, THOU art the fairiest in this hall, But Snow White's fairer than us all.….. WICKED QUEEN: (to mirror) For years you've tolD me I'm lovely anD fair, Competition is something I simply can't bear…… It's perfectly clear Snow White must go, But how to do it? - I think I know…… (calls to servant offstage) WICKED QUEEN: Bring me someone who knows the bush well, AnD to him my Devious plan I will tell...... (enter scout) WICKED QUEEN: Take Snow White into the bush, Take her to Govett's and give her a push…… (cackles) SCOUT: But she's such a fair child, So pure and young......! WICKED QUEEN : Do as I say and hold your tongue......! (both exit separately) SCENE 2 : In the bush near Govett's (typical Australian bush sounDs - kookooburras, chainsaws, 4WD' s, cruDe bushwalkers … enter Snow White accompanieD by scout) SCOUT: Do you aDmire the view my Dear? There's a pleasant picnic spot near here...... So here we are, a pleasant twosome, But I have a job that's really quite gruesome…… (aside) I'll sit down here and give her a drink, Before I shove her over the brink...... SNOW WHITE: We've walkeD all morning, anD my feet are so sore, I cant go on - I've blisters galore..... -

Blancanieves Se Despides De Los Siete Enanos: Snow White Says Goodbye to the Seven Dwarfs

Collage Volume 6 Number 1 Article 53 2012 Blancanieves se despides de los siete enanos: Snow White Says Goodbye to the Seven Dwarfs Daniel Persia Denison University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.denison.edu/collage Part of the Modern Languages Commons, Photography Commons, and the Poetry Commons Recommended Citation Persia, Daniel (2012) "Blancanieves se despides de los siete enanos: Snow White Says Goodbye to the Seven Dwarfs," Collage: Vol. 6 : No. 1 , Article 53. Available at: https://digitalcommons.denison.edu/collage/vol6/iss1/53 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Modern Languages at Denison Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Collage by an authorized editor of Denison Digital Commons. Photo by Charles O’Keefe Leopoldo María Panero (1948-) is a Spanish poet most commonly associated with the Novísimos, a reactionary, unconventional poetic group that began to question the basis of authority during Franco’s dictatorial regime. Panero’s voice is defiant yet resolute; his poetry deconstructs notions of identity by breaking traditional form. In Así se fundó Carnaby Street (1970), Panero creates a series of comic vignettes in poetic prose, distorting the reader’s memories of childhood innocence and re-mystifying a popular culture that has governed both past and present. Panero has spent much of his life in and out of psychiatric institutions, and consequently his representation of the aesthetic nightmare has evolved. Poemas del Manicomio de Mondragón (1999) reflects the shift in his poetry to a more twisted, obscure sense of futility and the nothingness that pervades human existence.