Molecular Architecture of SF3B and the Structural Basis of Splicing Modulation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

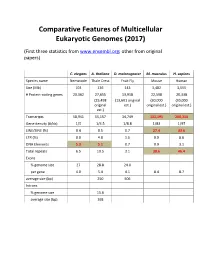

Eukaryotic Genome Annotation

Comparative Features of Multicellular Eukaryotic Genomes (2017) (First three statistics from www.ensembl.org; other from original papers) C. elegans A. thaliana D. melanogaster M. musculus H. sapiens Species name Nematode Thale Cress Fruit Fly Mouse Human Size (Mb) 103 136 143 3,482 3,555 # Protein-coding genes 20,362 27,655 13,918 22,598 20,338 (25,498 (13,601 original (30,000 (30,000 original est.) original est.) original est.) est.) Transcripts 58,941 55,157 34,749 131,195 200,310 Gene density (#/kb) 1/5 1/4.5 1/8.8 1/83 1/97 LINE/SINE (%) 0.4 0.5 0.7 27.4 33.6 LTR (%) 0.0 4.8 1.5 9.9 8.6 DNA Elements 5.3 5.1 0.7 0.9 3.1 Total repeats 6.5 10.5 3.1 38.6 46.4 Exons % genome size 27 28.8 24.0 per gene 4.0 5.4 4.1 8.4 8.7 average size (bp) 250 506 Introns % genome size 15.6 average size (bp) 168 Arabidopsis Chromosome Structures Sorghum Whole Genome Details Characterizing the Proteome The Protein World • Sequencing has defined o Many, many proteins • How can we use this data to: o Define genes in new genomes o Look for evolutionarily related genes o Follow evolution of genes ▪ Mixing of domains to create new proteins o Uncover important subsets of genes that ▪ That deep phylogenies • Plants vs. animals • Placental vs. non-placental animals • Monocots vs. dicots plants • Common nomenclature needed o Ensure consistency of interpretations InterPro (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/interpro/) Classification of Protein Families • Intergrated documentation resource for protein super families, families, domains and functional sites o Mitchell AL, Attwood TK, Babbitt PC, et al. -

Appendix 2. Significantly Differentially Regulated Genes in Term Compared with Second Trimester Amniotic Fluid Supernatant

Appendix 2. Significantly Differentially Regulated Genes in Term Compared With Second Trimester Amniotic Fluid Supernatant Fold Change in term vs second trimester Amniotic Affymetrix Duplicate Fluid Probe ID probes Symbol Entrez Gene Name 1019.9 217059_at D MUC7 mucin 7, secreted 424.5 211735_x_at D SFTPC surfactant protein C 416.2 206835_at STATH statherin 363.4 214387_x_at D SFTPC surfactant protein C 295.5 205982_x_at D SFTPC surfactant protein C 288.7 1553454_at RPTN repetin solute carrier family 34 (sodium 251.3 204124_at SLC34A2 phosphate), member 2 238.9 206786_at HTN3 histatin 3 161.5 220191_at GKN1 gastrokine 1 152.7 223678_s_at D SFTPA2 surfactant protein A2 130.9 207430_s_at D MSMB microseminoprotein, beta- 99.0 214199_at SFTPD surfactant protein D major histocompatibility complex, class II, 96.5 210982_s_at D HLA-DRA DR alpha 96.5 221133_s_at D CLDN18 claudin 18 94.4 238222_at GKN2 gastrokine 2 93.7 1557961_s_at D LOC100127983 uncharacterized LOC100127983 93.1 229584_at LRRK2 leucine-rich repeat kinase 2 HOXD cluster antisense RNA 1 (non- 88.6 242042_s_at D HOXD-AS1 protein coding) 86.0 205569_at LAMP3 lysosomal-associated membrane protein 3 85.4 232698_at BPIFB2 BPI fold containing family B, member 2 84.4 205979_at SCGB2A1 secretoglobin, family 2A, member 1 84.3 230469_at RTKN2 rhotekin 2 82.2 204130_at HSD11B2 hydroxysteroid (11-beta) dehydrogenase 2 81.9 222242_s_at KLK5 kallikrein-related peptidase 5 77.0 237281_at AKAP14 A kinase (PRKA) anchor protein 14 76.7 1553602_at MUCL1 mucin-like 1 76.3 216359_at D MUC7 mucin 7, -

Srsf10 and the Minor Spliceosome Control Tissue-Specific and Dynamic

SHORT REPORT Srsf10 and the minor spliceosome control tissue-specific and dynamic SR protein expression Stefan Meinke1, Gesine Goldammer1, A Ioana Weber1,2, Victor Tarabykin2, Alexander Neumann1†, Marco Preussner1*, Florian Heyd1* 1Freie Universita¨ t Berlin, Institute of Chemistry and Biochemistry, Laboratory of RNA Biochemistry, Berlin, Germany; 2Institute of Cell Biology and Neurobiology, Charite´-Universita¨ tsmedizin Berlin, corporate member of Freie Universita¨ t Berlin, Humboldt-Universita¨ t zu Berlin, and Berlin Institute of Health, Berlin, Germany Abstract Minor and major spliceosomes control splicing of distinct intron types and are thought to act largely independent of one another. SR proteins are essential splicing regulators mostly connected to the major spliceosome. Here, we show that Srsf10 expression is controlled through an autoregulated minor intron, tightly correlating Srsf10 with minor spliceosome abundance across different tissues and differentiation stages in mammals. Surprisingly, all other SR proteins also correlate with the minor spliceosome and Srsf10, and abolishing Srsf10 autoregulation by Crispr/ Cas9-mediated deletion of the autoregulatory exon induces expression of all SR proteins in a human cell line. Our data thus reveal extensive crosstalk and a global impact of the minor spliceosome on major intron splicing. *For correspondence: [email protected] (MP); [email protected] (FH) Introduction Present address: †Omiqa Alternative splicing (AS) is a major mechanism that controls gene expression (GE) and expands the Corporation, c/o Freie proteome diversity generated from a limited number of primary transcripts (Nilsen and Graveley, Universita¨ t Berlin, Altensteinstraße, Germany 2010). Splicing is carried out by a multi-megadalton molecular machinery called the spliceosome of which two distinct complexes exist. -

An Unusual Hydrophobic Core Confers Extreme Flexibility to HEAT Repeat Proteins

1596 Biophysical Journal Volume 99 September 2010 1596–1603 An Unusual Hydrophobic Core Confers Extreme Flexibility to HEAT Repeat Proteins Christian Kappel, Ulrich Zachariae, Nicole Do¨lker, and Helmut Grubmu¨ller* Department of Theoretical and Computational Biophysics, Max Planck Institute for Biophysical Chemistry, Go¨ttingen, Germany ABSTRACT Alpha-solenoid proteins are suggested to constitute highly flexible macromolecules, whose structural variability and large surface area is instrumental in many important protein-protein binding processes. By equilibrium and nonequilibrium molecular dynamics simulations, we show that importin-b, an archetypical a-solenoid, displays unprecedentedly large and fully reversible elasticity. Our stretching molecular dynamics simulations reveal full elasticity over up to twofold end-to-end extensions compared to its bound state. Despite the absence of any long-range intramolecular contacts, the protein can return to its equilibrium structure to within 3 A˚ backbone RMSD after the release of mechanical stress. We find that this extreme degree of flexibility is based on an unusually flexible hydrophobic core that differs substantially from that of structurally similar but more rigid globular proteins. In that respect, the core of importin-b resembles molten globules. The elastic behavior is dominated by nonpolar interactions between HEAT repeats, combined with conformational entropic effects. Our results suggest that a-sole- noid structures such as importin-b may bridge the molecular gap between completely structured and intrinsically disordered proteins. INTRODUCTION Solenoid proteins, consisting of repeating arrays of simple on repeat proteins focus on the folding and unfolding basic structural motifs, account for >5% of the genome of mechanism (14–16), an atomic force microscopy study on multicellular organisms (1). -

Supporting Information

Supporting Information Barquilla et al. 10.1073/pnas.0802668105 SI Materials and Methods The purification of recombinant GST proteins using glutathione Bioinformatics, Plasmids Constructs, and Cell Lines. Searches for T. Sepharose 4B (Amersham) was performed according to the brucei TOR, raptor, AVO3, and FKBP12 orthologues were manufacturer’s instructions and the proteins were dialyzed performed using GeneDB (www.genedb.org) and NCBI Blast against PBS. (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/BLAST/). Motif analyses were carried out using InterPro and Prosite. Antibodies. Mouse anti-TbFKBP12 monoclonal antibodies and GeneDB database accession numbers of these orthologues rabbit polyclonal anti-TOR antibodies were produced by inject- are: TbTOR1 (Tb10.6k15.2060), TbTOR2 (Tb927.4.420), ing the recombinant proteins into a BALB-C mouse or rabbit TbTOR-like 1 (Tb927.4.800), TbTOR-like 2 (Tb927.1.1930), using standard immunization protocols. Experiments involving TbRaptor (Tb11.03.0460), TbAVO3 (Tb927.8.3200), animals were approved by the National Animal Research Com- TbFKBP12 (Tb927.7.3420), and TbRaptor-like (Tb927.1.2190). mittee. Anti-TbFKBP12 antibodies were raised against the DNA fragments (400–700 bp) of the TbTOR1, TbTOR2, whole protein fused to GST, and hybridomes F12–3C7H11 and TbTOR-like 1, TbRaptor, TbAVO3, TbFKBP12, and TbRaptor- F12–7D10 H8 were selected by standard monoclonal selection like were amplified by PCR using pairs of specific primers (Table procedures as anti-TbFKBP12 monoclonal antibody producers. S1) and cloned into pGEM-T (Promega). All constructs were Anti-TbTOR antibodies were raised against nonhomologous sequenced to confirm that the subcloned DNA fragments had no TbTOR CЈ-terminal regions between the kinase domain and the mutations. -

'Design of Armadillo Repeat Protein Scaffolds'

Zurich Open Repository and Archive University of Zurich Main Library Strickhofstrasse 39 CH-8057 Zurich www.zora.uzh.ch Year: 2008 Design of armadillo repeat protein scaffolds Parmeggiani, F Posted at the Zurich Open Repository and Archive, University of Zurich ZORA URL: https://doi.org/10.5167/uzh-4818 Dissertation Published Version Originally published at: Parmeggiani, F. Design of armadillo repeat protein scaffolds. 2008, University of Zurich, Faculty of Medicine. Design of Armadillo Repeat Protein Scaffolds Dissertation zur Erlangung der naturwissenschaftlichen Doktorwürde (Dr. sc. nat.) vorgelegt der Mathematisch-naturwissenschaftlichen Fakultät der Universität Zürich von Fabio Parmeggiani aus Italien Promotionskomitee Prof. Dr. Andreas Plückthun (Leitung der Dissertation) Prof. Dr. Markus Grütter Prof. Dr. Donald Hilvert Zürich, 2008 To my grandfather, who showed me the essence of curiosity “It is easy to add more of the same to old knowledge, but it is difficult to explain the new” Benno Müller-Hill Table of Contents 1 Table of contents Summary 3 Chapter 1: Peptide binders 7 Part I: Peptide binders 8 Modular interaction domains as natural peptide binders 9 SH2 domains 10 PTB domains 10 PDZ domains 12 14-3-3 domains 12 SH3 domains 12 WW domains 12 Peptide recognition by major histocompatibility complexes 13 Repeat proteins targeting peptides 15 Armadillo repeat proteins 16 Tetratricopeptide repeat proteins (TPR) 16 Beta propellers 16 Peptide binding by antibodies 18 Alternative scaffolds: a new approach to peptide binding 20 Part -

Dissecting and Reprogramming the Folding and Assembly of Tandem-Repeat Proteins

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Apollo Dissecting and reprogramming the folding and assembly of tandem-repeat proteins Pamela J.E. Rowling1, Elin M. Sivertsson1, Albert Perez-Riba1, Ewan R. G. Main2*, Laura S. Itzhaki1* 1University of Cambridge Department of Pharmacology, Tennis Court Road, Cambridge CB2 1PD, UK. 2School of Biological and Chemical Sciences, Queen Mary, University of London, London E1 4NS, UK. *To whom correspondence should be addressed: [email protected] and [email protected] Studying protein folding and protein design in globular proteins presents significant challenges because of the two related features, topological complexity and cooperativity. In contrast, tandem-repeat proteins have regular and modular structures composed of linearly arrayed motifs. This means that the biophysics of even giant repeat proteins is highly amenable to dissection and to rational design. Here we discuss what has been learnt about the folding mechanisms of tandem- repeat proteins. The defining features that have emerged are: (i) accessibility of multiple distinct routes between denatured and native states, both at equilibrium and under kinetic conditions; (ii) different routes are favoured for folding versus unfolding; (iii) unfolding energy barriers are broad, reflecting stepwise unraveling of an array repeat by repeat; (iv) highly cooperative unfolding at equilibrium and the potential for exceptionally high thermodynamic stabilities by introducing consensus residues; (v) under force, helical-repeat structures are very weak with non-cooperative unfolding leading to elasticity and buffering effects. This level of understanding should enable us to create repeat proteins with made-to-measure folding mechanisms, in which one can dial into the sequence the order of repeat folding, number of pathways taken, step size (cooperativity) and fine-structure of the kinetic energy barriers. -

Spliceosomal Usnrnp Biogenesis, Structure and Function Cindy L Will* and Reinhard Lührmann†

290 Spliceosomal UsnRNP biogenesis, structure and function Cindy L Will* and Reinhard Lührmann† Significant advances have been made in elucidating the for each of the two reaction steps. Components of the biogenesis pathway and three-dimensional structure of the UsnRNPs also appear to catalyze the two transesterifi- UsnRNPs, the building blocks of the spliceosome. U2 and cation reactions leading to excision of the intron and U4/U6•U5 tri-snRNPs functionally associate with the pre-mRNA ligation of the 5′ and 3′ exons. Here we describe recent at an earlier stage of spliceosome assembly than previously advances in our understanding of snRNP biogenesis, thought, and additional evidence supporting UsnRNA-mediated structure and function, focusing primarily on the major catalysis of pre-mRNA splicing has been presented. spliceosomal UsnRNPs from higher eukaryotes. Addresses Identification of a novel UsnRNA export factor Max Planck Institute of Biophysical Chemistry, Department of Cellular UsnRNP biogenesis is a complex process, many aspects of Biochemistry, Am Fassberg 11, 37077 Göttingen, Germany. which remain poorly understood. Although less is known *e-mail: [email protected] about the maturation process of the minor U11, U12 and †e-mail: [email protected] U4atac UsnRNPs, it is assumed that they follow a pathway Current Opinion in Cell Biology 2001, 13:290–301 similar to that described below for the major UsnRNPs 0955-0674/01/$ — see front matter (see Figure 1). The UsnRNAs, with the exception of U6 © 2001 Elsevier Science Ltd. All rights reserved. and U6atac (see below), are transcribed by RNA polymerase II as snRNA precursors that contain additional Abbreviations ′ CBC cap-binding complex 3 nucleotides and acquire a monomethylated, m7GpppG NLS nuclear localization signal (m7G) cap structure. -

Trp53 Ablation Fails to Prevent Microcephaly in Mouse Pallium with Impaired Minor Intron Splicing

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.03.05.434172; this version posted March 6, 2021. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. Trp53 ablation fails to prevent microcephaly in mouse pallium with impaired minor intron splicing Running title: Cell cycle defects drive the microcephaly caused by minor splicing disruption. Alisa K. White1#, Marybeth Baumgartner2#, Madisen F. Lee1, Kyle D. Drake1, Gabriela S. Aquino1, Rahul N. Kanadia1,3,* 1Physiology and Neurobiology Department, University of Connecticut, Storrs, CT 06269, USA 2Department of Genetics, Yale School of Medicine, New Haven, CT 06510 3Institute of Systems Genomics, University of Connecticut, Storrs, CT 06269, USA #Authors contributed equally *Corresponding author Correspondence to Dr. Rahul N. Kanadia can be sent by mail, to 75 N Eagleville Rd, Storrs, CT 06269; by phone, at (860)-486-0286; or by e-mail, at [email protected]. Keywords. Cortical development; microcephaly; cell cycle; minor spliceosome; U11 snRNA bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.03.05.434172; this version posted March 6, 2021. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. Abstract. Mutations in minor spliceosome component RNU4ATAC, a small nuclear RNA (snRNA), are linked to primary microcephaly. We have reported that in the conditional knockout (cKO) mice for Rnu11, another minor spliceosome snRNA, minor intron splicing defect in minor intron-containing genes (MIGs) regulating cell cycle resulted in cell cycle defects, with a concomitant increase in γH2aX+ cells and p53-mediated apoptosis. -

Regulation of Adenovirus Alternative Pre-Mrna Splicing

Comprehensive Summaries of Uppsala Dissertations from the Faculty of Medicine 926 _____________________________ _____________________________ Regulation of Adenovirus Alternative Pre-mRNA Splicing Functional Characterization of Exonic and Intronic Splicing Enhancer Elements BY BAI-GONG YUE ACTA UNIVERSITATIS UPSALIENSIS UPPSALA 2000 Dissertation for the Degree of Doctor of Medical Science in Medical Virology presented at Uppsala University in 2000 ABSTRACT Yue, B-G. 2000. Regulation of adenovirus alternative pre-mRNA splicing. Functional characterization of exonic and intronic splicing enhancer elements. Acta Universitatis Upsaliensis. Comprehensive Summaries of Uppsala Dissertations from the Faculty of Medicine 926. 55pp. Uppsala. ISBN 91-554-4712-0 Pre-mRNA splicing and alternative pre-mRNA splicing are key regulatory steps controlling gene expression in higher eukaryotes. The work in this thesis was focused on a characterization of the significance of exonic and intronic splicing enhancer elements for pre- mRNA splicing. Previous studies have shown that removal of introns with weak and regulated splice sites require a splicing enhancer for activity. Here we extended these studies by demonstrating that two “strong” constitutively active introns, the adenovirus 52,55K and the Drosophila Ftz introns, are absolutely dependent on a downstream splicing enhancer for activity in vitro. Two types splicing enhancers were shown to perform redundant functions as activators of splicing. Thus, SR protein binding to an exonic splicing enhancer element or U1 snRNP binding to a downstream 5´splice site independently stimulated upstream intron removal. The data further showed that a 5´splice site was more effective and more versatile in activating splicing. Collectively the data suggest that a U1 enhancer is the prototypical enhancer element activating splicing of constitutively active introns. -

Comparative Features of Multicellular Eukaryotic Genomes (2017)

Comparative Features of Multicellular Eukaryotic Genomes (2017) (First three statistics from www.ensembl.org; other from original papers) C. elegans A. thaliana D. melanogaster M. musculus H. sapiens Species name Nematode Thale Cress Fruit Fly Mouse Human Size (Mb) 103 136 143 3,482 3,555 # Protein-coding genes 20,362 27,655 13,918 22,598 20,338 (25,498 (13,601 original (30,000 (30,000 original est.) original est.) original est.) est.) Transcripts 58,941 55,157 34,749 131,195 200,310 Gene density (#/kb) 1/5 1/4.5 1/8.8 1/83 1/97 LINE/SINE (%) 0.4 0.5 0.7 27.4 33.6 LTR (%) 0.0 4.8 1.5 9.9 8.6 DNA Elements 5.3 5.1 0.7 0.9 3.1 Total repeats 6.5 10.5 3.1 38.6 46.4 Exons % genome size 27 28.8 24.0 per gene 4.0 5.4 4.1 8.4 8.7 average size (bp) 250 506 Introns % genome size 15.6 average size (bp) 168 Arabidopsis Chromosome Structures Sorghum Whole Genome Details Characterizing the Proteome The Protein World • Sequencing has defined o Many, many proteins • How can we use this data to: o Define genes in new genomes o Look for evolutionarily related genes o Follow evolution of genes ▪ Mixing of domains to create new proteins o Uncover important subsets of genes that ▪ That deep phylogenies • Plants vs. animals • Placental vs. non-placental animals • Monocots vs. dicots plants • Common nomenclature needed o Ensure consistency of interpretations InterPro (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/interpro/) Classification of Protein Families • Intergrated documentation resource for protein super families, families, domains and functional sites o Mitchell AL, Attwood TK, Babbitt PC, et al. -

Appub0358.Pdf

Journal of Structural Biology 185 (2014) 147–162 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Journal of Structural Biology journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/yjsbi Designing protein function Modular peptide binding: From a comparison of natural binders to designed armadillo repeat proteins ⇑ Christian Reichen, Simon Hansen, Andreas Plückthun Department of Biochemistry, University of Zurich, 8057 Zurich, Switzerland article info abstract Article history: Several binding scaffolds that are not based on immunoglobulins have been designed as alternatives to Available online 3 August 2013 traditional monoclonal antibodies. Many of them have been developed to bind to folded proteins, yet cel- lular networks for signaling and protein trafficking often depend on binding to unfolded regions of pro- Keywords: teins. This type of binding can thus be well described as a peptide–protein interaction. In this review, we Protein engineering compare different peptide-binding scaffolds, highlighting that armadillo repeat proteins (ArmRP) offer an Libraries attractive modular system, as they bind a stretch of extended peptide in a repeat-wise manner. Instead of Proteomics generating each new binding molecule by an independent selection, preselected repeats – each comple- Protein design mentary to a piece of the target peptide – could be designed and assembled on demand into a new pro- Repeat proteins Peptide binding tein, which then binds the prescribed complete peptide. Stacked armadillo repeats (ArmR), each typically Protein–peptide interactions consisting of 42 amino acids arranged in three a-helices, build an elongated superhelical structure which enables binding of peptides in extended conformation. A consensus-based design approach, comple- mented with molecular dynamics simulations and rational engineering, resulted in well-expressed monomeric proteins with high stability.