Aberrant Splicing of U12-Type Introns Is the Hallmark of ZRSR2 Mutant Myelodysplastic Syndrome

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Splicing Factor U2AF1 Contributes to Cancer Progression Through a Noncanonical Role in Translation Regulation

Downloaded from genesdev.cshlp.org on September 30, 2021 - Published by Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press The splicing factor U2AF1 contributes to cancer progression through a noncanonical role in translation regulation Murali Palangat,1 Dimitrios G. Anastasakis,2 Dennis Liang Fei,3 Katherine E. Lindblad,4 Robert Bradley,5 Christopher S. Hourigan,4 Markus Hafner,2 and Daniel R. Larson1 1Laboratory of Receptor Biology and Gene Expression, National Cancer Insitute, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Maryland 20892, USA; 2National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Maryland 20892, USA; 3Weill Cornell Medicine, New York, New York 10065, USA; 4Laboratory of Myeloid Malignancies, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Maryland 20892, USA; 5Computational Biology Program, Public Health Sciences and Biological Sciences, Fred Hutchinson Cancer Center, Seattle, Washington 98109, USA Somatic mutations in the genes encoding components of the spliceosome occur frequently in human neoplasms, including myeloid dysplasias and leukemias, and less often in solid tumors. One of the affected factors, U2AF1, is involved in splice site selection, and the most common change, S34F, alters a conserved nucleic acid-binding domain, recognition of the 3′ splice site, and alternative splicing of many mRNAs. However, the role that this mutation plays in oncogenesis is still unknown. Here, we uncovered a noncanonical function of U2AF1, showing that it directly binds mature mRNA in the cytoplasm and negatively regulates mRNA translation. This splicing- independent role of U2AF1 is altered by the S34F mutation, and polysome profiling indicates that the mutation affects translation of hundreds of mRNA. -

EYS Mutations and Implementation of Minigene Assay for Variant

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN EYS mutations and implementation of minigene assay for variant classifcation in EYS‑associated retinitis pigmentosa in northern Sweden Ida Maria Westin1, Frida Jonsson1, Lennart Österman1, Monica Holmberg1, Marie Burstedt2 & Irina Golovleva1* Retinitis pigmentosa (RP) is a clinically and genetically heterogeneous group of inherited retinal degenerations. The ortholog of Drosophila eyes shut/spacemaker, EYS on chromosome 6q12 is a major genetic cause of recessive RP worldwide, with prevalence of 5 to 30%. In this study, by using targeted NGS, MLPA and Sanger sequencing we uncovered the EYS gene as one of the most common genetic cause of autosomal recessive RP in northern Sweden accounting for at least 16%. The most frequent pathogenic variant was c.8648_8655del that in some patients was identifed in cis with c.1155T>A, indicating Finnish ancestry. We also showed that two novel EYS variants, c.2992_2992+6delinsTG and c.3877+1G>A caused exon skipping in human embryonic kidney cells, HEK293T and in retinal pigment epithelium cells, ARPE‑19 demonstrating that in vitro minigene assay is a straightforward tool for the analysis of intronic variants. We conclude, that whenever it is possible, functional testing is of great value for classifcation of intronic EYS variants and the following molecular testing of family members, their genetic counselling, and inclusion of RP patients to future treatment studies. Retinitis pigmentosa (RP, MIM 268000) is a clinically and genetically heterogeneous group of inherited retinal degenerations (IRDs) causing primarily deterioration of the rod photoreceptors with subsequent worsening of the cones. It is classifed into two forms: syndromic (afecting other organs) and non-syndromic (not afect- ing other organs). -

Family Member in Teleost Fish Identification of a Novel IL-1 Cytokine

The Journal of Immunology Identification of a Novel IL-1 Cytokine Family Member in Teleost Fish1 Tiehui Wang,* Steve Bird,* Antonis Koussounadis,† Jason W. Holland,* Allison Carrington,* Jun Zou,* and Christopher J. Secombes2* A novel IL-1 family member (nIL-1F) has been discovered in fish, adding a further member to this cytokine family. The unique gene organization of nIL-1F, together with its location in the genome and low homology to known family members, suggests that this molecule is not homologous to known IL-1F. Nevertheless, it contains a predicted C-terminal -trefoil structure, an IL-1F signature region within the final exon, a potential IL-1 converting enzyme cut site, and its expression level is clearly increased following infection, or stimulation of macrophages with LPS or IL-1. A thrombin cut site is also present and may have functional relevance. The C-terminal recombinant protein antagonized the effects of rainbow trout rIL-1 on inflammatory gene expression in a trout macrophage cell line, suggesting it is an IL-1 antagonist. Modeling studies confirmed that nIL-1F has the potential to bind to the trout IL-1RI receptor protein, and may be a novel IL-1 receptor antagonist. The Journal of Immunology, 2009, 183: 962–974. he IL-1 family (IL-1F)3 of cytokines is characterized by of transcription factors such as NF-B and MAPK-regulated tran- their common secondary structure of an all- fold, the scription factors, leading to IL-1F-regulated gene transcription in T -trefoil, which they have in common with another cyto- the target cells (1). -

Coupling of Spliceosome Complexity to Intron Diversity

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.03.19.436190; this version posted March 20, 2021. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license. Coupling of spliceosome complexity to intron diversity Jade Sales-Lee1, Daniela S. Perry1, Bradley A. Bowser2, Jolene K. Diedrich3, Beiduo Rao1, Irene Beusch1, John R. Yates III3, Scott W. Roy4,6, and Hiten D. Madhani1,6,7 1Dept. of Biochemistry and Biophysics University of California – San Francisco San Francisco, CA 94158 2Dept. of Molecular and Cellular Biology University of California - Merced Merced, CA 95343 3Department of Molecular Medicine The Scripps Research Institute, La Jolla, CA 92037 4Dept. of Biology San Francisco State University San Francisco, CA 94132 5Chan-Zuckerberg Biohub San Francisco, CA 94158 6Corresponding authors: [email protected], [email protected] 7Lead Contact 1 bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.03.19.436190; this version posted March 20, 2021. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license. SUMMARY We determined that over 40 spliceosomal proteins are conserved between many fungal species and humans but were lost during the evolution of S. cerevisiae, an intron-poor yeast with unusually rigid splicing signals. We analyzed null mutations in a subset of these factors, most of which had not been investigated previously, in the intron-rich yeast Cryptococcus neoformans. -

The Dawn of Next Generation DNA Sequencing in Myelodysplastic Syndromes- Experience from Pakistan

The Dawn Of Next Generation DNA Sequencing In Myelodysplastic Syndromes- Experience From Pakistan. Nida Anwar ( [email protected] ) National Institute of Blood Diseases and Bone Marrow Transplantation Faheem Ahmed Memon Liaquat University of Medical & Health Sciences Saba Shahid National Institute of Blood Diseases and Bone Marrow Transplantation Muhammad Shakeel Jamil-ur-Rahman Center for Genome Research, University of Karachi Muhammad Irfan Jamil-ur-Rahman Center for Genome Research, University of Karachi Aisha Arshad National Institute of Blood Diseases and Bone Marrow Transplantation Arshi Naz Liaquat University of Medical & Health Sciences Ikram Din Ujjan Liaquat University of Medical & Health Sciences Tahir Shamsi National Institute of Blood Diseases and Bone Marrow Transplantation Research Article Keywords: Myelodysplastic Syndromes, Next generation sequencing, Gene analysis, Mutation, Pakistan. Posted Date: June 8th, 2021 DOI: https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-571430/v1 License: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Read Full License Page 1/16 Abstract Background: Myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS) are clonal disorders of hematopoietic stem cells exhibiting ineffective hematopoiesis and tendency for transformation into acute myeloid leukemia (AML). The available karyotyping and uorescent in situ hybridization provide limited information on molecular abnormalities for diagnosis/prognosis of MDS. Next generation DNA sequencing (NGS), providing deep insights into molecular mechanisms being involved in pathophysiology, was employed to study MDS in Pakistani cohort. Patients and Methods: It was a descriptive cross-sectional study carried out at National institute of blood diseases and bone marrow transplant from 2016 to 2019. Total of 22 cases of MDS were included. Complete blood counts, bone marrow assessment and cytogenetic analysis was done. -

A Computational Approach for Defining a Signature of Β-Cell Golgi Stress in Diabetes Mellitus

Page 1 of 781 Diabetes A Computational Approach for Defining a Signature of β-Cell Golgi Stress in Diabetes Mellitus Robert N. Bone1,6,7, Olufunmilola Oyebamiji2, Sayali Talware2, Sharmila Selvaraj2, Preethi Krishnan3,6, Farooq Syed1,6,7, Huanmei Wu2, Carmella Evans-Molina 1,3,4,5,6,7,8* Departments of 1Pediatrics, 3Medicine, 4Anatomy, Cell Biology & Physiology, 5Biochemistry & Molecular Biology, the 6Center for Diabetes & Metabolic Diseases, and the 7Herman B. Wells Center for Pediatric Research, Indiana University School of Medicine, Indianapolis, IN 46202; 2Department of BioHealth Informatics, Indiana University-Purdue University Indianapolis, Indianapolis, IN, 46202; 8Roudebush VA Medical Center, Indianapolis, IN 46202. *Corresponding Author(s): Carmella Evans-Molina, MD, PhD ([email protected]) Indiana University School of Medicine, 635 Barnhill Drive, MS 2031A, Indianapolis, IN 46202, Telephone: (317) 274-4145, Fax (317) 274-4107 Running Title: Golgi Stress Response in Diabetes Word Count: 4358 Number of Figures: 6 Keywords: Golgi apparatus stress, Islets, β cell, Type 1 diabetes, Type 2 diabetes 1 Diabetes Publish Ahead of Print, published online August 20, 2020 Diabetes Page 2 of 781 ABSTRACT The Golgi apparatus (GA) is an important site of insulin processing and granule maturation, but whether GA organelle dysfunction and GA stress are present in the diabetic β-cell has not been tested. We utilized an informatics-based approach to develop a transcriptional signature of β-cell GA stress using existing RNA sequencing and microarray datasets generated using human islets from donors with diabetes and islets where type 1(T1D) and type 2 diabetes (T2D) had been modeled ex vivo. To narrow our results to GA-specific genes, we applied a filter set of 1,030 genes accepted as GA associated. -

4-6 Weeks Old Female C57BL/6 Mice Obtained from Jackson Labs Were Used for Cell Isolation

Methods Mice: 4-6 weeks old female C57BL/6 mice obtained from Jackson labs were used for cell isolation. Female Foxp3-IRES-GFP reporter mice (1), backcrossed to B6/C57 background for 10 generations, were used for the isolation of naïve CD4 and naïve CD8 cells for the RNAseq experiments. The mice were housed in pathogen-free animal facility in the La Jolla Institute for Allergy and Immunology and were used according to protocols approved by the Institutional Animal Care and use Committee. Preparation of cells: Subsets of thymocytes were isolated by cell sorting as previously described (2), after cell surface staining using CD4 (GK1.5), CD8 (53-6.7), CD3ε (145- 2C11), CD24 (M1/69) (all from Biolegend). DP cells: CD4+CD8 int/hi; CD4 SP cells: CD4CD3 hi, CD24 int/lo; CD8 SP cells: CD8 int/hi CD4 CD3 hi, CD24 int/lo (Fig S2). Peripheral subsets were isolated after pooling spleen and lymph nodes. T cells were enriched by negative isolation using Dynabeads (Dynabeads untouched mouse T cells, 11413D, Invitrogen). After surface staining for CD4 (GK1.5), CD8 (53-6.7), CD62L (MEL-14), CD25 (PC61) and CD44 (IM7), naïve CD4+CD62L hiCD25-CD44lo and naïve CD8+CD62L hiCD25-CD44lo were obtained by sorting (BD FACS Aria). Additionally, for the RNAseq experiments, CD4 and CD8 naïve cells were isolated by sorting T cells from the Foxp3- IRES-GFP mice: CD4+CD62LhiCD25–CD44lo GFP(FOXP3)– and CD8+CD62LhiCD25– CD44lo GFP(FOXP3)– (antibodies were from Biolegend). In some cases, naïve CD4 cells were cultured in vitro under Th1 or Th2 polarizing conditions (3, 4). -

Minor Intron Retention Drives Clonal Hematopoietic Disorders and Diverse Cancer Predisposition

ARTICLES https://doi.org/10.1038/s41588-021-00828-9 Minor intron retention drives clonal hematopoietic disorders and diverse cancer predisposition Daichi Inoue1,2,12, Jacob T. Polaski 3,12, Justin Taylor 4,12, Pau Castel 5, Sisi Chen2, Susumu Kobayashi1,6, Simon J. Hogg2, Yasutaka Hayashi1, Jose Mario Bello Pineda3,7,8, Ettaib El Marabti2, Caroline Erickson2, Katherine Knorr2, Miki Fukumoto1, Hiromi Yamazaki1, Atsushi Tanaka1,9, Chie Fukui1, Sydney X. Lu2, Benjamin H. Durham 2, Bo Liu2, Eric Wang2, Sanjoy Mehta10, Daniel Zakheim10, Ralph Garippa10, Alex Penson2, Guo-Liang Chew 11, Frank McCormick 5, Robert K. Bradley 3,7 ✉ and Omar Abdel-Wahab 2 ✉ Most eukaryotes harbor two distinct pre-mRNA splicing machineries: the major spliceosome, which removes >99% of introns, and the minor spliceosome, which removes rare, evolutionarily conserved introns. Although hypothesized to serve important regulatory functions, physiologic roles of the minor spliceosome are not well understood. For example, the minor spliceosome component ZRSR2 is subject to recurrent, leukemia-associated mutations, yet functional connections among minor introns, hematopoiesis and cancers are unclear. Here, we identify that impaired minor intron excision via ZRSR2 loss enhances hemato- poietic stem cell self-renewal. CRISPR screens mimicking nonsense-mediated decay of minor intron-containing mRNA species converged on LZTR1, a regulator of RAS-related GTPases. LZTR1 minor intron retention was also discovered in the RASopathy Noonan syndrome, due to intronic mutations disrupting splicing and diverse solid tumors. These data uncover minor intron rec- ognition as a regulator of hematopoiesis, noncoding mutations within minor introns as potential cancer drivers and links among ZRSR2 mutations, LZTR1 regulation and leukemias. -

Supplementary Table S4. FGA Co-Expressed Gene List in LUAD

Supplementary Table S4. FGA co-expressed gene list in LUAD tumors Symbol R Locus Description FGG 0.919 4q28 fibrinogen gamma chain FGL1 0.635 8p22 fibrinogen-like 1 SLC7A2 0.536 8p22 solute carrier family 7 (cationic amino acid transporter, y+ system), member 2 DUSP4 0.521 8p12-p11 dual specificity phosphatase 4 HAL 0.51 12q22-q24.1histidine ammonia-lyase PDE4D 0.499 5q12 phosphodiesterase 4D, cAMP-specific FURIN 0.497 15q26.1 furin (paired basic amino acid cleaving enzyme) CPS1 0.49 2q35 carbamoyl-phosphate synthase 1, mitochondrial TESC 0.478 12q24.22 tescalcin INHA 0.465 2q35 inhibin, alpha S100P 0.461 4p16 S100 calcium binding protein P VPS37A 0.447 8p22 vacuolar protein sorting 37 homolog A (S. cerevisiae) SLC16A14 0.447 2q36.3 solute carrier family 16, member 14 PPARGC1A 0.443 4p15.1 peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma, coactivator 1 alpha SIK1 0.435 21q22.3 salt-inducible kinase 1 IRS2 0.434 13q34 insulin receptor substrate 2 RND1 0.433 12q12 Rho family GTPase 1 HGD 0.433 3q13.33 homogentisate 1,2-dioxygenase PTP4A1 0.432 6q12 protein tyrosine phosphatase type IVA, member 1 C8orf4 0.428 8p11.2 chromosome 8 open reading frame 4 DDC 0.427 7p12.2 dopa decarboxylase (aromatic L-amino acid decarboxylase) TACC2 0.427 10q26 transforming, acidic coiled-coil containing protein 2 MUC13 0.422 3q21.2 mucin 13, cell surface associated C5 0.412 9q33-q34 complement component 5 NR4A2 0.412 2q22-q23 nuclear receptor subfamily 4, group A, member 2 EYS 0.411 6q12 eyes shut homolog (Drosophila) GPX2 0.406 14q24.1 glutathione peroxidase -

Pan-Cancer Analysis Identifies Mutations in SUGP1 That Recapitulate Mutant SF3B1 Splicing Dysregulation

Pan-cancer analysis identifies mutations in SUGP1 that recapitulate mutant SF3B1 splicing dysregulation Zhaoqi Liua,b,c,1, Jian Zhangd,1, Yiwei Suna,c, Tomin E. Perea-Chambleea,b,c, James L. Manleyd,2, and Raul Rabadana,b,c,2 aProgram for Mathematical Genomics, Columbia University, New York, NY 10032; bDepartment of Systems Biology, Columbia University, New York, NY 10032; cDepartment of Biomedical Informatics, Columbia University, New York, NY 10032; and dDepartment of Biological Sciences, Columbia University, New York, NY 10027 Contributed by James L. Manley, March 2, 2020 (sent for review January 2, 2020; reviewed by Kristen Lynch and Gene Yeo) The gene encoding the core spliceosomal protein SF3B1 is the most also resulted in the same splicing defects observed in SF3B1 frequently mutated gene encoding a splicing factor in a variety of mutant cells (11). hematologic malignancies and solid tumors. SF3B1 mutations in- In addition to SF3B1, other SF-encoding genes have also been duce use of cryptic 3′ splice sites (3′ss), and these splicing errors found to be mutated in hematologic malignancies, e.g., U2AF1, contribute to tumorigenesis. However, it is unclear how wide- SRSF2, and ZRSR2. However, these SF gene mutations do not spread this type of cryptic 3′ss usage is in cancers and what is share common alterations in splicing (1, 3), suggesting that dif- the full spectrum of genetic mutations that cause such missplicing. ferent splicing patterns may contribute to different phenotypes To address this issue, we performed an unbiased pan-cancer anal- of cancers. Because SF3B1 is the most frequently mutated ysis to identify genetic alterations that lead to the same aberrant splicing gene, the splicing defects caused by mutant SF3B1 may SF3B1 splicing as observed with mutations. -

Cellular Minigene Models for the Study of Allelic Expression of the Tau Gene and Its Role in Progressive Supranuclear Palsy

CELLULAR MINIGENE MODELS FOR THE STUDY OF ALLELIC EXPRESSION OF THE TAU GENE AND ITS ROLE IN PROGRESSIVE SUPRANUCLEAR PALSY Victoria Anne Kay Thesis submitted in the fulfilment of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Reta Lila Weston Institute of Neurological Studies Institute of Neurology University College London March 2013 Declaration I, Victoria Kay, confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this has been indicated in the thesis. 2 Abstract Progressive supranuclear palsy (PSP) belongs to a group of neurodegenerative disorders that are characterised by hallmark pathology consisting of intra-neuronal aggregates of the microtubule-associated protein, tau. In PSP, these aggregates are almost exclusively composed of one of the two major tau protein isoform groups normally expressed at similar levels in the healthy brain, indicating a role for altered isoform regulation in PSP aetiology. Although no causal mutations have been identified, common variation within the gene encoding tau, MAPT, has been highly associated with PSP risk. The A-allele of the rs242557 single nucleotide polymorphism has been repeatedly shown to significantly increase the risk of developing PSP. Its location within a distal region of the MAPT promoter region is significant, with independent studies – including this one – demonstrating that the rs242557-A allele alters the function of a transcription regulatory domain. As transcription and alternative splicing processes have been shown to be co-regulated in some genes, it was hypothesised that the rs242557-A allele could directly affect MAPT alternative splicing through its differential effect on transcription. -

(P -Value<0.05, Fold Change≥1.4), 4 Vs. 0 Gy Irradiation

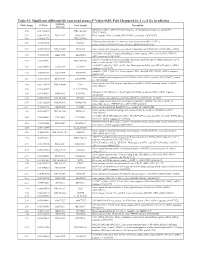

Table S1: Significant differentially expressed genes (P -Value<0.05, Fold Change≥1.4), 4 vs. 0 Gy irradiation Genbank Fold Change P -Value Gene Symbol Description Accession Q9F8M7_CARHY (Q9F8M7) DTDP-glucose 4,6-dehydratase (Fragment), partial (9%) 6.70 0.017399678 THC2699065 [THC2719287] 5.53 0.003379195 BC013657 BC013657 Homo sapiens cDNA clone IMAGE:4152983, partial cds. [BC013657] 5.10 0.024641735 THC2750781 Ciliary dynein heavy chain 5 (Axonemal beta dynein heavy chain 5) (HL1). 4.07 0.04353262 DNAH5 [Source:Uniprot/SWISSPROT;Acc:Q8TE73] [ENST00000382416] 3.81 0.002855909 NM_145263 SPATA18 Homo sapiens spermatogenesis associated 18 homolog (rat) (SPATA18), mRNA [NM_145263] AA418814 zw01a02.s1 Soares_NhHMPu_S1 Homo sapiens cDNA clone IMAGE:767978 3', 3.69 0.03203913 AA418814 AA418814 mRNA sequence [AA418814] AL356953 leucine-rich repeat-containing G protein-coupled receptor 6 {Homo sapiens} (exp=0; 3.63 0.0277936 THC2705989 wgp=1; cg=0), partial (4%) [THC2752981] AA484677 ne64a07.s1 NCI_CGAP_Alv1 Homo sapiens cDNA clone IMAGE:909012, mRNA 3.63 0.027098073 AA484677 AA484677 sequence [AA484677] oe06h09.s1 NCI_CGAP_Ov2 Homo sapiens cDNA clone IMAGE:1385153, mRNA sequence 3.48 0.04468495 AA837799 AA837799 [AA837799] Homo sapiens hypothetical protein LOC340109, mRNA (cDNA clone IMAGE:5578073), partial 3.27 0.031178378 BC039509 LOC643401 cds. [BC039509] Homo sapiens Fas (TNF receptor superfamily, member 6) (FAS), transcript variant 1, mRNA 3.24 0.022156298 NM_000043 FAS [NM_000043] 3.20 0.021043295 A_32_P125056 BF803942 CM2-CI0135-021100-477-g08 CI0135 Homo sapiens cDNA, mRNA sequence 3.04 0.043389246 BF803942 BF803942 [BF803942] 3.03 0.002430239 NM_015920 RPS27L Homo sapiens ribosomal protein S27-like (RPS27L), mRNA [NM_015920] Homo sapiens tumor necrosis factor receptor superfamily, member 10c, decoy without an 2.98 0.021202829 NM_003841 TNFRSF10C intracellular domain (TNFRSF10C), mRNA [NM_003841] 2.97 0.03243901 AB002384 C6orf32 Homo sapiens mRNA for KIAA0386 gene, partial cds.