MECCA: Cosmopolis in the Desert

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Signifying Notiiing That Which Is Not There

liUlillIMI.IIJ thresholds 19 Signifying Notiiing This article seeks to ground itself In two literal understandings of the invisible, that is, as something, which is simply not there, or as some- thing which has been hidden. It works out from the intuitive response to the human body as a commonplace object with which we are all inti- mately familiar, and of which we commonly expected a state of com- plete presence to be normal. The body is of course also an object to which strategies of covering and exposure are applied, in a highly differ- entiated set of systems across times and cultures. That Which Is Not There A discomforting thought. I had sufficient elbow room to begin writing this on a Greyhound bus only because the young woman seated next to me had no arm from above the elbow, or at least, from above where her elbow should have been. That which is not there grasps, uninvited, our attention. j^ ^^^ ^^^^ ^^^ ^^^ ^^ ^^^ other. Another story about a chair and a missing arm. There is a chair, designed by Lutyens that has but one arm. One cannot sit in this chair without assuming a certain pose, legs crossed, left hand resting, fingers curled, on one's right thigh, right hand, raised to the chin, perhaps fram- ing one's mouth, holding the others' attention to one's face, one's con- versation. It is difficult for anyone at all comfortable within his or her own skin not to assume that pose, or the demeanor which that pose accompanies. If one is not comfortable, the only choice is to sit bolt "We deliberately left out one arm- upright, hands together on one's lap, perhaps fidgeting the one with the rest to give more ease to the body. -

Downloaded from Brill.Com09/27/2021 10:32:48PM Via Free Access 266 Index

Index ʿAbd al-Nāṣir, Jamāl (Nasser) 233, 234 Almássy, László 233 ʿAbd al-Raḥmān 143, 144, 151, 152, 154 Americas 171 Abd-el-Wahad (Moroccan resident in Mecca) American Oil Company 230 128 Arab Abdülhamid ii (Sultan-Caliph and Khādim Bureau/Bureaux arabes (military system of al-Ḥaramayn) 71, 115 administration) 96, 121 ʿAbdullāh Saʿīd al-Damlūjī 196 hygiene 194 Abdur Rahman 95, 96 migrants in Poland 156 Ablonczy, Balázs 227 Revolt 96, 97 Abraham 137, 166 Arabia (see Saudi Arabia) Abul Fazl 23 Arabian Abu-Qubays (mount) 128 Peninsula 5, 119, 143 Aceh 28, 93 horse, walking on pilgrims 166 Aden 11, 25, 90, 96, 99, 101, 145, 154 architecture 166 Afghanistan 95, 103, 115, 207 music and dancing girls 165, 167 Africa 34, 41, 81, 95, 99, 113, 121, 143, 144, 148, sea 21 150, 171, 192, 198, 240 ʿArafāt África ( journal) 261 the Day of 209, 210, 211 Africanism 241 the Mountain of 90, 151, 185, 200, 201, 204, Akbar Nama 23 207, 209, 210, 223 Akbar (Emperor) 23, 30, 37 the Plain of 97, 212 ʿAlawī, Aḥmad b. Muṣṭafā al- 251 Arenberg (d’), Auguste 130 ʿAlawiyya (Sufi order) 251 Armenian 4, 148 Al-Azhar x, 221, 222, 223, 232, 233, 234, 259 Attas, Said Hossein al- 201 Album with photographs of Polish mosques Asad, Muḥammad (Weiss, Leopold) 174, 195 177 Asia 10, 16, 17, 20, 21, 24, 30, 34, 38, 43, 47, 52, Albuquerque, Alfonso de 19 59, 81, 95, 107 Alcohol 150, 230 Assimilationist 212 Alexandria 143, 144, 154, 222, 227, 229, 240, Asssemblé Nationale (French Parliament) 249, 258 121 Alexandria Aurangzeb 31 Fuad i Airport in 257 Australia 171 Spanish consul -

Spring 2021 H Volume 25 No

Spring 2021 H Volume 25 No. 1 2021 Virtual Homes Tour Premieres June 17! reservation Austin’s 2021 Virtual Ticket buyers will experience the living Homes Tour, “Rogers-Washington- history of one of East Austin’s most Holy Cross: Black Heritage, Living intact historic neighborhoods through History,” will premiere on Thursday, interviews with longtime residents and Virtual Homes Tour June 17 at 7:00 pm CST. This year’s homeowners, historic documentation, Thursday, June 17, 2021 virtual tour will feature the incredible and rich videography. Viewers will 7PM premiere, followed by Q&A postwar homes and histories of East also hear from architectural historian Austin’s Rogers-Washington-Holy Dr. Tara Dudley on the works of $20/PA members $25/Non-members Cross Historic District, Austin’s first architect John S. Chase, FAIA, whose historic district celebrating Black early career was forged through heritage. The 45-minute video will be personal connection to Rogers- Tickets on sale at followed by a live Q&A session via Washington-Holy Cross and whose preservationaustin.org Zoom. work has left an indelible mark on the historic district. Continued on page 3 PA Welcomes Meghan King 2020-2021 Board of Directors W e’re delighted to welcome Meghan King, our new Programs and Outreach Planner! H EXECUTIVE COMMITEE H Meghan came on board in Decem- Clayton Bullock, President Melissa Barry, VP ber 2020 as Preservation Austin’s Allen Wise, President-Elect Linda Y. Jackson, VP third full-time staff member. Clay Cary, Treasurer Christina Randle, Secretary Hailing from Canada, Meghan Lori Martin, Immediate Past President attributes her lifelong love for H DIRECTORS H American architectural heritage Katie Carmichael Harmony Grogan Kelley McClure to her childhood summers spent travelling the United States visiting Miriam Conner Patrick Johnson Alyson McGee Frank Lloyd Wright sites with her father. -

The Architecture of Excess

The Architecture of Excess Image Fabrication between Spectacle and Anaesthesia A Master’s Thesis for the Degree Master of Arts (Two Years) in Visual Culture Andrei Deacu Spring semester 2012 Supervisor: Anders Michelsen Andrei Deacu Title and subtitle: The Architecture of Excess: Image Fabrication between Spectacle and Anaesthesia Author: Andrei Deacu Supervisor: Anders Michelsen Division of Art History and Visual Studies Abstract This thesis explores the interplay between the architectural image and its collective meaning in the contemporary society. It starts from a wonder around the capacity of architectural project The Cloud towers, created by the widely known architectural company MVRDV, to ignite fervent reactions caused by its resemblance to the image of the World Trade Centre Towers exploding. While questioning the detachment of architectural image from content, the first part of this thesis discusses the changes brought into the image-meaning relation in the spectacle society in postmodernism, using concepts as simulacra and anaesthesia as key vectors. In the second part of the thesis, the architectural simulacrum is explored through the cases of Dubai as urbanscape and The Jewish Museum Berlin as monument. The final part of the thesis concludes while using the case study of The Cloud project, and hints towards the ambivalence of image-content detachment and the possibility of architectural images to become social commentaries. 2 Andrei Deacu Table of contents 1. Introduction 1a. The problem 4 1b. Relevance of the subject 4 1c. Theoretical foundation and structure 5 2. From Spectacle to Anaesthesia 2a. The Architectural Image as the Expression of Society 7 2b. The Simulacrum 10 2c. -

The Arab and Arab Islamic and Muslim Architecture

Copyright is owned by the Author of the thesis. Permission is given for a copy to be downloaded by an individual for the purpose of research and private study only. The thesis may not be reproduced elsewhere without the permission of the Author. THE ARAB AND ARAB ISLAMIC AND MUSLIM ARCHITECTURE OF THE OLD HOLY MASJID AND AL-KA'ABAH A Monadic Interpretation of the Two Holy Buildings by Eduard Franciscus Schwarz A Thesis Submitted to Massey University Wellington Campus, New Zealand in Part Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Philosophy Massey University of Wellington 2005 The Holy Complex in Makkah al-Mukarramah in Saudi Arabia Acknowledgments Although I belong to those who were indirectly indoctrinated by the Bauhaus, Architecture has moved well away from the Bauhaus architecture and Bauhaus philosophy into that can be referred to as labyrinth architecture with a poetic base. However, the tendency to perceive architecture as a body poetic needs to be queried. That architecture had moved away from the architecture advocated by the Bauhaus was particularly realized during my study at Massey University, Wellington Campus, during 2004. Contact with art students and staff, trained in art and fashion were very useful. Without the help of others, the writing of the thesis would have been more difficult. My thanks go to Professor Duncan Joiner, who was my supervisor. I am also thankful to the Massey University Library, Wellington Campus that carried out a literature search in support of this work. Massey University also provided me with computers for the writing of the work, Brian Halliday, now retired, needs mentioning here, so does Ken Elliot for the constant help he gave computer-wise. -

The Aesthetics and Greatness of the Kiswah of the Kaaba in the Saudi Era

International Journal of Islamic and Civilizational Studies Full Paper UMRAN The Aesthetics and Greatness of the Kiswah of the Kaaba in the Saudi Era Duaa Mohammed Alashari*, Abd.Rahman Hamzah, Nurazmallail Marni Academy of Islamic Civilization, Faculty of Social Sciences and Humanities, Universiti Teknologi Malaysia, 81310 UTM Johor Bahru, Malaysia *Corresponding author: [email protected] Article history Received: 2020-04-08 Received in revised form: 2020-10-15 Accepted: 2020-10-16 Published online: 2021-02-28 Abstract The Kaaba has a long history and considered as praising and sacredness for Muslim all over the Islamic world. The Kaaba garment (kiswah) received during the Saudi era meticulous attention in terms of quality of artistry, implementation and manufacture. The most important feature that distinguished the Kaaba dress and added to its aesthetic value is the Arabic calligraphy and Islamic motifs. these arts are illuminate and decorate the Kiswah of the Kaaba. Also, the Kiswah of the Kaaba is a sign of respect, honour and reverence for The Holy House. This study is an investigation into the aesthetics of the Kiswah of the Kaaba during the Saudi era. The study aims to expose the aesthetics and spirituality of the Kaaba gown in the Saudi period. The research employed the descriptive method through, using this method, the researcher was able to knowledge about the kiswah of the kaaba as well as about Arabic calligraphy that embellishment the Kiswah by artistically executed. Moreover, this research aims to study the aesthetic value of the Kiswah of the kabab that under the supervision of the calligrapher Moktar Alam. -

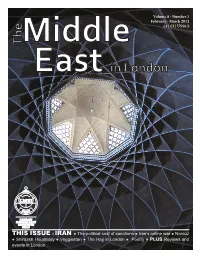

Narguess Farzad SOAS Membership – the Largest Concentration of Middle East Expertise in Any Institution in Europe

Volume 8 - Number 3 February - March 2012 £4 | €5 | US$6.5 THIS ISSUE : IRAN ● The political cost of sanctions ● Iran’s online war ● Norouz ● Shirazeh Houshiary ● Veggiestan ● The Hajj in London ● Poetry ● PLUS Reviews and events in London Volume 8 - Number 3 February - March 2012 £4 | €5 | US$6.5 THIS ISSUE : IRAN ● The political cost of sanctions ● Iran’s online war ● Norouz ● Shirazeh Houshiary ● Veggiestan ● The Hajj in London ● Poetry ● PLUS Reviews and events in London Interior of the dome of the house at Dawlat Abad Garden, Home of Yazd Governor in 1750 © Dr Justin Watkins About the London Middle East Institute (LMEI) Volume 8 - Number 3 February – March 2012 Th e London Middle East Institute (LMEI) draws upon the resources of London and SOAS to provide teaching, training, research, publication, consultancy, outreach and other services related to the Middle Editorial Board East. It serves as a neutral forum for Middle East studies broadly defi ned and helps to create links between Nadje Al-Ali individuals and institutions with academic, commercial, diplomatic, media or other specialisations. SOAS With its own professional staff of Middle East experts, the LMEI is further strengthened by its academic Narguess Farzad SOAS membership – the largest concentration of Middle East expertise in any institution in Europe. Th e LMEI also Nevsal Hughes has access to the SOAS Library, which houses over 150,000 volumes dealing with all aspects of the Middle Association of European Journalists East. LMEI’s Advisory Council is the driving force behind the Institute’s fundraising programme, for which Najm Jarrah it takes primary responsibility. -

Textile Arts and Aesthetics in and Beyond the Medieval Islamic World

Perspective Actualité en histoire de l’art 1 | 2016 Textiles Crossroads of Cloth: Textile Arts and Aesthetics in and beyond the Medieval Islamic World Aux carrefours des étoffes : les arts et l’esthétique textiles dans le monde islamique médiéval et au-delà Vera-Simone Schulz Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/perspective/6309 DOI: 10.4000/perspective.6309 ISSN: 2269-7721 Publisher Institut national d'histoire de l'art Printed version Date of publication: 30 June 2016 Number of pages: 93-108 ISBN: 978-2-917902-31-8 ISSN: 1777-7852 Electronic reference Vera-Simone Schulz, « Crossroads of Cloth: Textile Arts and Aesthetics in and beyond the Medieval Islamic World », Perspective [Online], 1 | 2016, Online since 15 June 2017, connection on 01 October 2020. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/perspective/6309 ; DOI : https://doi.org/10.4000/ perspective.6309 Vera-Simone Schulz Crossroads of Cloth: Textile Arts and Aesthetics in and beyond the Medieval Islamic World A piece of woven silk preserved in the Cooper-Hewitt National Design Museum in New York (fig. 1) shows medallions with pearl borders in which various animals appear. The elephants, winged horses, and composite creatures with dog heads and peacock tails are positioned alternately face-to-face and back-to-back. The fabric is designed to be viewed both from a distance and more closely. From a distance, the overall structure with its repeating pattern forms a grid in which geometrical roundels oscillate between contact and isolation. They are so close they seem almost to touch both each other and the complicated vegetal patterns in the spaces between, although in fact each roundel remains separate from every other visual element in the textile. -

Exhibition of Two Holy Mosques Architecture

Exhibition of Two Holy Mosques Architecture النسخة اإلنجليزية Special IssueMakky In the Name of Allah, the Most Gracious, the Most Merciful This issue has been released in cooperation with the General Presidency for the Affairs of the Praise be to Allah, the Lord of all Grand Mosque and the Prophet's Mosque creation, and peace and blessings on the Messenger of Allah -Prophet Mohammad- and on his companions and followers. Dear sons and daughters, With the advent of Islam and for more than 14 centuries, the Two Holy Mosques occupy a special place in the hearts of all Muslims. Serving and caring for these two sacred shrines has always been regarded as a great honor and a sincere act of devotion. History bears witness to the massive architectural achievements and the extended efforts of Muslim rulers since the early Islamic period to restore and renovate these two holy sites. Today, the steps and initiatives taken by our blessed government to maintain and enhance the standards of the facilities and services of the Two Head of the General Presidency for the Holy Mosques are gaining momentum. These endeavors are Affairs of the Grand Mosque and the embraced and fostered by the Custodian of the Two Holy Mosques, His Majesty King Salman ibn Abdulaziz, and His Royal Highness Prophet's Mosque Crown Prince, Mohammad ibn Salman. Their continuous support to Dr. Abdur-Rahman Abdulaziz As-Sudais implement major expansion and development works that combine majestic architecture with modern technology has induced a Deputy Head of Media major shift in the services provided for the visitors of the Two Holy Relations & Affairs Mosques. -

The Icon Project: Architecture, Cities and Capitalist Globalization: Introduction

Leslie Sklair The icon project: architecture, cities and capitalist globalization: introduction Book section (Accepted version) Original citation: Sklair, Leslie (2017) The icon project: architecture, cities and capitalist globalization. Oxford University Press, Oxon, UK. ISBN 9780190464189 © 2017 The Author This version available at: http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/71859/ Available in LSE Research Online: April 2017 LSE has developed LSE Research Online so that users may access research output of the School. Copyright © and Moral Rights for the papers on this site are retained by the individual authors and/or other copyright owners. Users may download and/or print one copy of any article(s) in LSE Research Online to facilitate their private study or for non-commercial research. You may not engage in further distribution of the material or use it for any profit-making activities or any commercial gain. You may freely distribute the URL (http://eprints.lse.ac.uk) of the LSE Research Online website. This document is the author’s submitted version of the book section. There may be differences between this version and the published version. You are advised to consult the publisher’s version if you wish to cite from it. THE ICON PROJECT architecture, cities, and capitalist globalization LESLIE SKLAIR OUP UNCORRECTED PROOF – REVISES, Thu Dec 08 2016, NEWGEN Introduction Never before in the history of human society has the capacity to produce and deliver goods and services been so efficient and so enormous, thanks to the electronic revolution that started in the 1960s and the global logistics revolution made possible by the advent of the shipping container. -

Hidden Cities: Reinventing the Non-Space Between Street and Subway

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2018 Hidden Cities: Reinventing The Non-Space Between Street And Subway Jae Min Lee University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the Architecture Commons, and the Urban Studies and Planning Commons Recommended Citation Lee, Jae Min, "Hidden Cities: Reinventing The Non-Space Between Street And Subway" (2018). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 2984. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/2984 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/2984 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Hidden Cities: Reinventing The Non-Space Between Street And Subway Abstract The connections leading to underground transit lines have not received the attention given to public spaces above ground. Considered to be merely infrastructure, the design and planning of these underground passageways has been dominated by engineering and capital investment principles, with little attention to place-making. This underground transportation area, often dismissed as “non-space,” is a by-product of high-density transit-oriented development, and becomes increasingly valuable and complex as cities become larger and denser. This dissertation explores the design of five of these hidden cities where there has been a serious effort to make them into desirable public spaces. Over thirty-two million urbanites navigate these underground labyrinths in New York City, Hong Kong, London, Moscow, and Paris every day. These in-between spaces have evolved from simple stairwells to networked corridors, to transit concourses, to transit malls, and to the financial engines for affordable public transit. -

Alhawasli Et Al.Pub

JOURNAL OF ISLAMIC ARCHITECTURE P-ISSN: 2086-2636 E-ISSN: 2356-4644 Journal Home Page: http://ejournal.uin-malang.ac.id/index.php/JIA THE IMPACT OF HOLY KAABA CUBIC SHAPE ON THE INCORPOREAL SPACE | Received May 4th, 2018 | Accepted July 27th, 2018 | Available Online December 15th, 2018 | | DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.18860/jia.v5i2.5040 | Hiba Alhawasli ABSTRACT Department of Architecture Engineering The Holy Kaaba is the house of God; the home of greatness secrets, wisdom Tarbiat Modares University, Tehran, Iran and divine beauty, which is reflected in all his creatures. This study aims to [email protected] find the role of the shape of holy Kaaba in producing such kind of spaces and discovering the characteristics possessed by its form which has an impact in Mohammad Reza Bemanian creating such incorporeal space. In this study, scientific articles and Department of Architecture Engineering research were used to achieve the rules of research theory with taking into Tarbiat Modares University, Tehran, Iran account considering the position of Islamic theoretical and practical wisdom. [email protected] In the process of creating works of art, architecture and joint issues with urbanization, and by using the rational method to find out, in the end, the study shows the space of Holy Kaaba is a sign of divine glory from visualization and embodiment material. The nature veil in this space shines the divine light in human conscience. Human perception of space is related to his knowledge of himself and the world. Human in the use of space is approaches to percepts the true meaning of it.