Hidden Cities: Reinventing the Non-Space Between Street and Subway

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Railway Operations Management (ECROM)

Executive Certificate in Railway Operations Management (ECROM) Available Summer 2020 Hear from MTR’s experts and other industry Flexible leaders on the core strategic principles of Take advantage of the flexibility offered by the new delivery mode. managing railway operations as well as best Maximise your investment by matching your learning focus against the available choices of “Premium Pack”, “Design-my-own Pack” or the practices in daily operations management, with “Hot-topic Module”. applications drawn from MTR’s considerable expertise in metro operations management. Who Should Attend Executives, managers and decision-makers employed by railway operators and authorities, who are keen to broaden their knowledge in rail operations and management. The ECROM programme will be predominately delivered through virtual classrooms and Language supplemented with a one-day site visit in Hong Kong. English At the end of the site visit, a graduation ceremony and networking event will be held. Participants Feedback 2017 – 2019 statistics 90% 92% Live Stream Live Training Networking Virtual Classroom Site Visit Group Satisfaction Rating Recommend to Others Executive Certificate in Railway Operations Management (ECROM) Overview The modular syllabus kicks off with macroscopic discussions on high level transport policy as pertaining to the development of modern societies. Subsequent sessions take a practical look at MTR’s strategies for meeting passenger demand and service benchmarks, with special focus on customer service, maintenance strategies, -

TRAFFIC ADVICE Temporary Traffic and Transport Arrangements On

TRAFFIC ADVICE Temporary Traffic and Transport Arrangements on Des Voeux Road Central, Central Motorists are advised that to facilitate emergency road works, the following temporary traffic and transport arrangements will be implemented from 9.00 am to 6.00 am of the following day on 15 August 2020: A. Road Closure Des Voeux Road Central eastbound between Pedder Street and Murray Road. B. Traffic Diversion Affected vehicles on Des Voeux Road Central eastbound heading for Queensway eastbound will be diverted via Chater Road eastbound and Murray Road southbound. C. Public Transport Arrangements D. Bus Routes Direction Route diversions Suspended bus stops Temporary bus stops NWFB Route To diverted via · Des Voeux Road · Chater Road Central outside No. 25 Braemar Chater Road, opposite Statue Square Statue Hill Murray Road Square NWFB Route To Yiu and resume No. 722 Tung their original Estate routeings XHT Route To Kwun No. 101 Tong XHT Route To Pak No. 104 Tin Estate XHT Route To Ho No. 109 Man Tin Estate Bus Routes Direction Route diversions Suspended bus stops Temporary bus stops XHT Route To Ping No. 111 Shek Estate XHT Route To Choi No. 113 Hung XHT Route To No. 115 Kowloon City Ferry Pier XHT Route To Sha No. 182 Tin XHT Route To Tai Po No. 307 Centre XHT Route To Sheung No. 373 Shui XHT Route To Ping No. 603 Tin XHT Route To Shun No. 619 Lee Estate XHT Route To Kai No. 641 Tak XHT Route To Sheung No. 673 Shui XHT Route To Ma On No. 681P Shan XHT Route To Tseung No. -

180 Water Street

THE RETAIL AT WATER S TREET 18FIDI/NYC 0 MULTIPLE OPPORTUNITIES EXTRAORDINARY EXPOSURE WATER STREET BETWEEN FLETCHER AND JOHN STREETS VIEW FROM JOHN AND PEARL STREETS LIMITLESS POTENTIAL Be surrounded by an ever-growing population of tourists, office workers and residents. 180 Water Street offers more than 9,200 SF of retail space located directly across from the Seaport District and in close proximity to the Fulton Street station and the Staten Island Ferry. Ground Floor Space B Proposed Division | Ground Floor UP TO 9,221 SF OF DIVISIBLE RETAIL (COMING SOON) LOCATED AT THE BASE OF A 573-UNIT, 34 3 IN FT, SPACE A 1,285 SF PEARL STREETPEARL REDEVELOPED LUXURY STREETPEARL RESIDENTIAL BUILDING 1,535 SF 2,407 SF 62 FT SPACE B Ground Floor 4,012 SF WATER STREET WATER Space A 1,285 SF* (COMING SOON) 62 FT ELEVATOR Space B 4,012 SF* LOBBY *Divisible 58 SF Lower Level 65 FT 25 FT 6 FT 34 FT 3,924 SF JOHN STREET JOHN STREET Ceiling Heights Ground Floor Space A 26 FT Space B 13 FT 7 IN Lower Level 14 FT Lower Level Space B Proposed Division | Lower Level Features New Façade Potential dedicated entrance for Lower Level, see proposed division All uses considered including cooking SPACE B 3,924 SF 3,924 SF ELEVATOR A ROBUST MARKET 7,945 Hotel rooms in lower Manhattan as of 2018 14.6M Visitors to Lower Manhattan in 2018 87,979,022 S F Total office square footage in lower Manhattan 1,143 Retail stores and restaurants in Lower Manhattan (and rising), 105M Annual transit riders in Lower Manhattan 330 Mixed-use and residential buildings with an estimated -

Spring 2021 H Volume 25 No

Spring 2021 H Volume 25 No. 1 2021 Virtual Homes Tour Premieres June 17! reservation Austin’s 2021 Virtual Ticket buyers will experience the living Homes Tour, “Rogers-Washington- history of one of East Austin’s most Holy Cross: Black Heritage, Living intact historic neighborhoods through History,” will premiere on Thursday, interviews with longtime residents and Virtual Homes Tour June 17 at 7:00 pm CST. This year’s homeowners, historic documentation, Thursday, June 17, 2021 virtual tour will feature the incredible and rich videography. Viewers will 7PM premiere, followed by Q&A postwar homes and histories of East also hear from architectural historian Austin’s Rogers-Washington-Holy Dr. Tara Dudley on the works of $20/PA members $25/Non-members Cross Historic District, Austin’s first architect John S. Chase, FAIA, whose historic district celebrating Black early career was forged through heritage. The 45-minute video will be personal connection to Rogers- Tickets on sale at followed by a live Q&A session via Washington-Holy Cross and whose preservationaustin.org Zoom. work has left an indelible mark on the historic district. Continued on page 3 PA Welcomes Meghan King 2020-2021 Board of Directors W e’re delighted to welcome Meghan King, our new Programs and Outreach Planner! H EXECUTIVE COMMITEE H Meghan came on board in Decem- Clayton Bullock, President Melissa Barry, VP ber 2020 as Preservation Austin’s Allen Wise, President-Elect Linda Y. Jackson, VP third full-time staff member. Clay Cary, Treasurer Christina Randle, Secretary Hailing from Canada, Meghan Lori Martin, Immediate Past President attributes her lifelong love for H DIRECTORS H American architectural heritage Katie Carmichael Harmony Grogan Kelley McClure to her childhood summers spent travelling the United States visiting Miriam Conner Patrick Johnson Alyson McGee Frank Lloyd Wright sites with her father. -

The Architecture of Excess

The Architecture of Excess Image Fabrication between Spectacle and Anaesthesia A Master’s Thesis for the Degree Master of Arts (Two Years) in Visual Culture Andrei Deacu Spring semester 2012 Supervisor: Anders Michelsen Andrei Deacu Title and subtitle: The Architecture of Excess: Image Fabrication between Spectacle and Anaesthesia Author: Andrei Deacu Supervisor: Anders Michelsen Division of Art History and Visual Studies Abstract This thesis explores the interplay between the architectural image and its collective meaning in the contemporary society. It starts from a wonder around the capacity of architectural project The Cloud towers, created by the widely known architectural company MVRDV, to ignite fervent reactions caused by its resemblance to the image of the World Trade Centre Towers exploding. While questioning the detachment of architectural image from content, the first part of this thesis discusses the changes brought into the image-meaning relation in the spectacle society in postmodernism, using concepts as simulacra and anaesthesia as key vectors. In the second part of the thesis, the architectural simulacrum is explored through the cases of Dubai as urbanscape and The Jewish Museum Berlin as monument. The final part of the thesis concludes while using the case study of The Cloud project, and hints towards the ambivalence of image-content detachment and the possibility of architectural images to become social commentaries. 2 Andrei Deacu Table of contents 1. Introduction 1a. The problem 4 1b. Relevance of the subject 4 1c. Theoretical foundation and structure 5 2. From Spectacle to Anaesthesia 2a. The Architectural Image as the Expression of Society 7 2b. The Simulacrum 10 2c. -

Helsinki Conference on Emotions, Populism and Polarisation

#HEPP2 HEPP2 HELSINKI CONFERENCE ON EMOTIONS, POPULISM AND POLARISATION 4 – 8 May 2021 #mainstreamingpopulism Opening #HEPP2 JUHA HERKMAN (UNIVERSITY OF HELSINKI) HEPP2 ORGANISING COMMITTEE CHAIR WELCOME Keynote session 1 – Chair: Juha Herkman KATJA VALASKIVI AND JOHANNA SUMIALA (UNIVERSITY OF HELSINKI) COVID-19, QANON AND EPISTEMIC INSTABILITY: THE CIRCULATION HEPP2 Conference OF CONSPIRACY THEORIES IN THE HYBRID MEDIA ENVIRONMENT Tuesday 4 May 2021 10:00 – 11:30 #mainstreamingpopulism 11:45 – 13:15 Panel 1.1 #HEPP2 Chair: Virpi Salojärvi IAMCR’s Crisis, Security and Conflict Communication Working Group Special panel: Inequality, crisis and technology at a crossroads Maria Avraamidou (University of Cyprus) Migrant racialisation on Twitter during a border and a pandemic crisis Irina Milutinovic (Institute of European Studies Belgrade) The role of media in the political polarisation of the public within the unconsolidated democracy regime HEPP2 Conference Ionut Chiruta (University of Tartu) Covid-19: Performing control through sedimented Tuesday discursive norms on mainstream media in Romania 4 May 2021 Ssu-Han Yu (London School of Economics and Political Science) Mediating polarisation and populism: An inter-generational analysis #mainstreamingpopulism #HEPP2 11:45 – 13:15 Panel 1.2 Chair: Tuula Vaarakallio From Yellow Vests to public debate Gwenaëlle Bauvois (University of Helsinki) Are the Yellow Vests populists? A definitional exploration of the Yellow Vests movement Ingeborg Misje Bergem (University of Oslo) Covid-19’s effect on the -

Newly Completed Babington Hill Residences at Mid-Levels West Now on the Market

Love・Home Newly completed Babington Hill residences at Mid-Levels West now on the market Babington Hill, the latest SHKP residential project in the traditional Island West district, is nestled amidst lush greenery in close proximity to excellent transport links and famous schools. These residences have been finished to exacting standards and boast fashionable interiors with a distinctive appearance. Units are now on the market receiving an encouraging response. The best of everything Babington Hill is a rare new development for the area offering a range of 79 quality residential units with two to four bedroom layouts, all with outdoor areas, such as a balcony, utility platform, flat roof and/or roof to create an open, comfortable living environment. The development benefits from the use of high-quality building materials. The exterior design features a large number of glass curtain walls to provide transparency and create a spacious feeling. The clean and comfortable interior includes a luxurious private clubhouse equipped with a gym and an outdoor swimming pool. Famous schools and convenient transport The Development is situated next to the University of Hong Kong and Dean's Residence in the Mid-Levels of Hong Kong Island. It is near the Lung Fu Shan hiking trails, which provides quick and easy access to nature as well as a sanctuary of peace and tranquility. The area is home to a traditional and well-established network of elite schools, such as St. Paul's College, St. Stephen's Girls' College and St. Joseph's College, all of which provide excellent scholastic environments for the next generation to learn and thrive. -

Mirage Architecture Project

National pavilion of UKRAINE at the Venice Biennale of Architecture 2012 сommissar Nikita Mazayev сurator of Ukrainian participation Olilga Milenty сurator Alexander Ponomarev MIRAGE ARCHITECTURE PROJECT Alexander Ponomarev Alexey Kozyr Ilya Babak Sergey Shestakov GAZE Pаvilion. Arsenale (Artiglierie) National pavilion of Ukraine at the Venice Biennale of Architecture National pavilion MIRAGE ARCHITECTURE PROJECT of UKRAINE Commissar Nikita Mazayev at the Venice Curator of Ukrainian participation Olilga Milenty Biennale of Architecture Curator Alexander Ponomarev 2012 Coordination Maria Elfimova Technical coordination Vladimir Pirogov, Alexander Chentsov, Alexander Pavlov, Alexey Podoxenov, Vitaliy Pasikov Modeling and video editing Ivan Fomin, Alexander Kytmanov Graphic design Alёna Ivanova-Johanson With the support of Joint Transportation Company, VIART-GROUP, “Kirill” MIRAGE ARCHITECTURE PROJECT This catalogue is published in conjunction with the exhibition Alexander Ponomarev Mirage Architecture Project Editor and compiler Alёna Ivanova-Johanson Alexey Kozyr Text Alexey Muratov, Sergey Khachaturov, Alessandro De Magistris Translation Ludmila Lezhneva, Tatiana Podkorytova Ilya Babak Layout Alёna Ivanova-Johanson Color correction Dmitry Shevlyakov Sergey Shestakov Printing Papergraf S.r.L., Padova, Italy 2012 All texts © the authors, 2012 © graphic design, Alёna Ivanova-Johanson, 2012 prOJECTS A great miracle appeared beyond Kiev! Suddenly one could see far away to every part of the world. The Liman went blue at a distance, and the Black Sea splashed wide beyond the Liman. The worldly-wise recognized the Crimea, which rose from the sea like a mountain, and the marshy Sivash. The land of Galicia was seen on the right. ‘And what’s that?’ asked the people who had gathered around, pointing at the gray and white tops which lurched far beyond in the sky and looked more like clouds. -

Rail Merger (1) Connected Transactions (2) Very Substantial Acquisition

THIS CIRCULAR IS IMPORTANT AND REQUIRES YOUR IMMEDIATE ATTENTION This Circular does not constitute, or form part of, an offer or invitation, or solicitation or inducement of an offer, to subscribe for or purchase any of the MTRC Shares or other securities of the Company. If you are in any doubt as to any aspect of this Circular, or as to the action to be taken, you should consult a licensed securities LR 14.63(2)(b) dealer, bank manager, solicitor, professional accountant or other professional adviser. LR 14A.58(3)(b) If you have sold or transferred all your MTRC Shares, you should at once hand this Circular to the purchaser or transferee or to the bank, licensed securities dealer or other agent through whom the sale or transfer was effected for transmission to the purchaser or transferee. The Stock Exchange of Hong Kong Limited takes no responsibility for the contents of this Circular, makes no representation as to its LR 14.58(1) accuracy or completeness and expressly disclaims any liability whatsoever for any loss howsoever arising from or in reliance upon the LR 14A.59(1) whole or any part of the contents of this Circular. App. 1B, 1 LR 13.51A RAIL MERGER (1) CONNECTED TRANSACTIONS (2) VERY SUBSTANTIAL ACQUISITION Joint Financial Advisers to the Company Goldman Sachs (Asia) L.L.C. UBS Investment Bank Independent Financial Adviser to the Independent Board Committee and the Independent Shareholders Merrill Lynch (Asia Pacific) Limited It is important to note that the purpose of distributing this Circular is to provide the Independent Shareholders of the Company with information, amongst other things, on the proposed Rail Merger, so that they may make an informed decision on voting in respect of the EGM Resolution. -

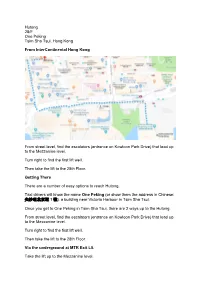

Hutong 28/F One Peking Tsim Sha Tsui, Hong Kong From

Hutong 28/F One Peking Tsim Sha Tsui, Hong Kong From InterContinental Hong Kong From street level, find the escalators (entrance on Kowloon Park Drive) that lead up to the Mezzanine level. Turn right to find the first lift well. Then take the lift to the 28th Floor. Getting There There are a number of easy options to reach Hutong. Taxi drivers will know the name One Peking (or show them the address in Chinese: 尖沙咀北京道 1 號), a building near Victoria Harbour in Tsim Sha Tsui. Once you get to One Peking in Tsim Sha Tsui, there are 2 ways up to the Hutong. From street level, find the escalators (entrance on Kowloon Park Drive) that lead up to the Mezzanine level. Turn right to find the first lift well. Then take the lift to the 28th Floor. Via the underground at MTR Exit L5. Take the lift up to the Mezzanine level. Make your way around to the first lift well to your right. Then take the lift to the 28th Floor. From Central Via the MTR (Central Station) (10 minutes) 1. Take the Tsuen Wan Line [Red] towards Tsuen Wan 2. Alight at Tsim Sha Tsui Station 3. Take Exit L5 straight to the entrance of One Peking building 4. Take the lift to the 28th Floor Via the Star Ferry (Central Pier) (15 mins) 1. Take the Star Ferry toward Tsim Sha Tsui 2. Disembark at Tsim Sha Tsui pier and follow Sallisbury Road toward Kowloon Park 3. Drive crossing Canton Road 4. Turn left onto Kowloon Park Drive and walk toward the end of the block, the last building before the crossing is One Peking 5. -

TRACING the Constructlvist INFLUENCES on the BUILDINGS of EKATERINBURG, RUSSIA

BERLIK Ir ACSA EUROPEAN CONFERENCE TRACING THE CONSTRUCTlVIST INFLUENCES ON THE BUILDINGS OF EKATERINBURG, RUSSIA CAROL BUHRMANN University of Kentucky The Sources In the formerly closed Soviet city of Sverdlovsk,now Ekaterinburg, architects undertook a massive building campaign of hundreds of buildings during the Soviet Union's first five year plan, 1928 to 1933. Many of these buildings still exist and in them can be seen the urge to express connections between concept andmaking. These connections were forged from the desire to construct meaningful architectural iconography in the newly formed Soviet Union that would reflect an entirely new social structure. Although a great variety of innovative architecture was being explored in Moscow as early as 1914, it wasn't until the first five year plan that constructivist ideas were utilized extensively throughout the Soviet Union.' Sverdlovsk was to be developed in the 1920s and 1930s as one of the most heavily industrial Fig. 1. Russia. cities in Russia. The construction of vast factories, the expansion of the city, the programming of new workers and the replacement of Czarist and religious memory was supported by an architectural program of constructivist notion that new styles are the product of changing architecture. More buildings were built in Sverdlovsk structural techniques and changing social, functional during this era, per capita, than in either Moscow or requirements. He theorizes that architecture, since Leningrad.L These buildings may reflect more accurately antiquity, expresses itself cyclically: The youth of a new the politics and social climate in the Soviet Union than the style is reflected in "constructive" form, maturity well examined constructivist architecture in both Moscow expressed in organic form and the decay of style is and Leningrad. -

How to Get to HKU from the Airport? Chinese Texts for Locations in Hong Kong And

How to get to HKU from the Airport? (By MTR: Airport – Hong Kong Station – Central Station – HKU Station) At Hong Kong International Airport, the easiest way to get to the city is by the Airport Express train at the arrival terminal. You get off the train at the last stop ("Hong Kong Station"). At Hong Kong station, follow the sign in the MTR station to walk to Central station, take the train in Island Line and get off at HKU station. The two stations are connected by underground tunnels and automated walkways. If you want to go to the main campus, you go to Exit A and take the lift to Exit A2. The whole journey to HKU will take about 45 minutes and costs about HKD120. (By Taxi: Airport - HKU) Another way from the airport to HKU is by taxi, which will take about 35 minutes and cost about HKD350. Note that drivers take cash only (rather than credit cards) and you should take RED taxis, available at Airport Taxi Station. Chinese texts for locations in Hong Kong and HKU The following Chinese texts may be useful when you need to ask for directions or let the driver know of the destination. You may show this page and bring along with you. English Chinese (中文) The University of Hong Kong 香港大學 Hong Kong International Airport 香港國際機場 http://www.maps.hku.hk Department of Mathematics, 4th Floor, Run Run Shaw Building HKU Station Exit A2 Lift Lobby How to get to Robert Black College (RBC) from the Airport? (By MTR: Airport – Hong Kong Station – Central Station – HKU Station) RBC (for accommodation) is in HKU campus.