The Arab and Arab Islamic and Muslim Architecture

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Signifying Notiiing That Which Is Not There

liUlillIMI.IIJ thresholds 19 Signifying Notiiing This article seeks to ground itself In two literal understandings of the invisible, that is, as something, which is simply not there, or as some- thing which has been hidden. It works out from the intuitive response to the human body as a commonplace object with which we are all inti- mately familiar, and of which we commonly expected a state of com- plete presence to be normal. The body is of course also an object to which strategies of covering and exposure are applied, in a highly differ- entiated set of systems across times and cultures. That Which Is Not There A discomforting thought. I had sufficient elbow room to begin writing this on a Greyhound bus only because the young woman seated next to me had no arm from above the elbow, or at least, from above where her elbow should have been. That which is not there grasps, uninvited, our attention. j^ ^^^ ^^^^ ^^^ ^^^ ^^ ^^^ other. Another story about a chair and a missing arm. There is a chair, designed by Lutyens that has but one arm. One cannot sit in this chair without assuming a certain pose, legs crossed, left hand resting, fingers curled, on one's right thigh, right hand, raised to the chin, perhaps fram- ing one's mouth, holding the others' attention to one's face, one's con- versation. It is difficult for anyone at all comfortable within his or her own skin not to assume that pose, or the demeanor which that pose accompanies. If one is not comfortable, the only choice is to sit bolt "We deliberately left out one arm- upright, hands together on one's lap, perhaps fidgeting the one with the rest to give more ease to the body. -

Downloaded from Brill.Com09/27/2021 10:32:48PM Via Free Access 266 Index

Index ʿAbd al-Nāṣir, Jamāl (Nasser) 233, 234 Almássy, László 233 ʿAbd al-Raḥmān 143, 144, 151, 152, 154 Americas 171 Abd-el-Wahad (Moroccan resident in Mecca) American Oil Company 230 128 Arab Abdülhamid ii (Sultan-Caliph and Khādim Bureau/Bureaux arabes (military system of al-Ḥaramayn) 71, 115 administration) 96, 121 ʿAbdullāh Saʿīd al-Damlūjī 196 hygiene 194 Abdur Rahman 95, 96 migrants in Poland 156 Ablonczy, Balázs 227 Revolt 96, 97 Abraham 137, 166 Arabia (see Saudi Arabia) Abul Fazl 23 Arabian Abu-Qubays (mount) 128 Peninsula 5, 119, 143 Aceh 28, 93 horse, walking on pilgrims 166 Aden 11, 25, 90, 96, 99, 101, 145, 154 architecture 166 Afghanistan 95, 103, 115, 207 music and dancing girls 165, 167 Africa 34, 41, 81, 95, 99, 113, 121, 143, 144, 148, sea 21 150, 171, 192, 198, 240 ʿArafāt África ( journal) 261 the Day of 209, 210, 211 Africanism 241 the Mountain of 90, 151, 185, 200, 201, 204, Akbar Nama 23 207, 209, 210, 223 Akbar (Emperor) 23, 30, 37 the Plain of 97, 212 ʿAlawī, Aḥmad b. Muṣṭafā al- 251 Arenberg (d’), Auguste 130 ʿAlawiyya (Sufi order) 251 Armenian 4, 148 Al-Azhar x, 221, 222, 223, 232, 233, 234, 259 Attas, Said Hossein al- 201 Album with photographs of Polish mosques Asad, Muḥammad (Weiss, Leopold) 174, 195 177 Asia 10, 16, 17, 20, 21, 24, 30, 34, 38, 43, 47, 52, Albuquerque, Alfonso de 19 59, 81, 95, 107 Alcohol 150, 230 Assimilationist 212 Alexandria 143, 144, 154, 222, 227, 229, 240, Asssemblé Nationale (French Parliament) 249, 258 121 Alexandria Aurangzeb 31 Fuad i Airport in 257 Australia 171 Spanish consul -

The Aesthetics and Greatness of the Kiswah of the Kaaba in the Saudi Era

International Journal of Islamic and Civilizational Studies Full Paper UMRAN The Aesthetics and Greatness of the Kiswah of the Kaaba in the Saudi Era Duaa Mohammed Alashari*, Abd.Rahman Hamzah, Nurazmallail Marni Academy of Islamic Civilization, Faculty of Social Sciences and Humanities, Universiti Teknologi Malaysia, 81310 UTM Johor Bahru, Malaysia *Corresponding author: [email protected] Article history Received: 2020-04-08 Received in revised form: 2020-10-15 Accepted: 2020-10-16 Published online: 2021-02-28 Abstract The Kaaba has a long history and considered as praising and sacredness for Muslim all over the Islamic world. The Kaaba garment (kiswah) received during the Saudi era meticulous attention in terms of quality of artistry, implementation and manufacture. The most important feature that distinguished the Kaaba dress and added to its aesthetic value is the Arabic calligraphy and Islamic motifs. these arts are illuminate and decorate the Kiswah of the Kaaba. Also, the Kiswah of the Kaaba is a sign of respect, honour and reverence for The Holy House. This study is an investigation into the aesthetics of the Kiswah of the Kaaba during the Saudi era. The study aims to expose the aesthetics and spirituality of the Kaaba gown in the Saudi period. The research employed the descriptive method through, using this method, the researcher was able to knowledge about the kiswah of the kaaba as well as about Arabic calligraphy that embellishment the Kiswah by artistically executed. Moreover, this research aims to study the aesthetic value of the Kiswah of the kabab that under the supervision of the calligrapher Moktar Alam. -

MECCA: Cosmopolis in the Desert

MECCA: Cosmopolis in the Desert THE HOLY CITY: ARCHITECTURE AND URBAN LIFE IN THE SHADOW OF GOD Salma Damluji Introduction In 1993, I was asked to head the project for documenting of The Holy Mosques of Makkah and Madinah Extension. The project was based at Areen Design, London, the architectural office associate of the Saudi Bin Ladin Group. Completed in Summer 1994, the research and documentation was published in 1998.1 Several factors contributed to the complexity of the task that was closely associated with the completion of the Second Saudi Extension that commenced in 1989 and was completed in 1991. Foremost was the nature of the design and construction processes taking place and an alienated attempt at reinventing “Islamic Architecture”. This was fundamentally superficial and the architecture weak, verging on vulgar. The constant dilemma, or enigma, lay in the actual project: a most challenging architectural venture, symbolic and equally honourable, providing the historic occasion for a significant architectural statement. The rendering, it soon became apparent, was unworthy of the edifice and its historical or architectural connotations. In brief an architectural icon, the heart of Islam, was to be determined by contractors. The assigned team of architects and engineers responsible were intellectually removed and ill equipped, both from cultural knowledge, design qualification or the level of speciality required to deal with this immense, sensitive and architecturally foreboding task. The Beirut based engineering firm, Dar al Handasah, was originally granted the contract and commenced the job. We have no information on whether the latter hired specialised architects or conducted any research to consolidate their design. -

Narguess Farzad SOAS Membership – the Largest Concentration of Middle East Expertise in Any Institution in Europe

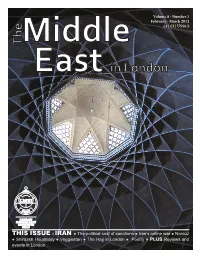

Volume 8 - Number 3 February - March 2012 £4 | €5 | US$6.5 THIS ISSUE : IRAN ● The political cost of sanctions ● Iran’s online war ● Norouz ● Shirazeh Houshiary ● Veggiestan ● The Hajj in London ● Poetry ● PLUS Reviews and events in London Volume 8 - Number 3 February - March 2012 £4 | €5 | US$6.5 THIS ISSUE : IRAN ● The political cost of sanctions ● Iran’s online war ● Norouz ● Shirazeh Houshiary ● Veggiestan ● The Hajj in London ● Poetry ● PLUS Reviews and events in London Interior of the dome of the house at Dawlat Abad Garden, Home of Yazd Governor in 1750 © Dr Justin Watkins About the London Middle East Institute (LMEI) Volume 8 - Number 3 February – March 2012 Th e London Middle East Institute (LMEI) draws upon the resources of London and SOAS to provide teaching, training, research, publication, consultancy, outreach and other services related to the Middle Editorial Board East. It serves as a neutral forum for Middle East studies broadly defi ned and helps to create links between Nadje Al-Ali individuals and institutions with academic, commercial, diplomatic, media or other specialisations. SOAS With its own professional staff of Middle East experts, the LMEI is further strengthened by its academic Narguess Farzad SOAS membership – the largest concentration of Middle East expertise in any institution in Europe. Th e LMEI also Nevsal Hughes has access to the SOAS Library, which houses over 150,000 volumes dealing with all aspects of the Middle Association of European Journalists East. LMEI’s Advisory Council is the driving force behind the Institute’s fundraising programme, for which Najm Jarrah it takes primary responsibility. -

Hajj the Islamic Pilgrimage According to the Five Schools of Islamic Law

Published on Books on Islam and Muslims | Al-Islam.org (http://www.al-islam.org) Home > Hajj The Islamic Pilgrimage According to The Five Schools of Islamic Law Hajj The Islamic Pilgrimage According to The Five Schools of Islamic Law Log in [1] or register [2] to post comments Adapted from "The Five Schools of Islamic Law" Author(s): ● Allamah Muhammad Jawad Maghniyyah [3] Publisher(s): ● Ansariyan Publications - Qum [4] Category: ● Hajj (Pilgrimage) [5] Topic Tags: ● Hajj [6] ● Schools of Thought [7] ● Law [8] ● Fiqh [9] Old url: http://www.al-islam.org/hajjandfiveschools/ The Hajj The Acts of the Hajj At the beginning, in order to make it easier for the reader to follow the opinions of the five schools of fiqh about various aspects of Hajj, we shall briefly outline their sequence as ordained by the Shari'ah. The Hajj pilgrim coming from a place distant from Mecca assumes ihram1 from the miqat2 on his way, or from a point parallel to the closest miqat, and starts reciting the talbiyah.3 In this there is no difference between one performing `Umrah mufradahor any of the three types of Hajj (i.e. tamattu, ifrad, qiran). However, those who live within the haram4 of Mecca assume ihram from their houses.'5 i.e. `God is the greatest') and tahlil) اﻟﻠَّﻪِ أَﻛْﺒَﺮ On sighting the Holy Ka'bah, he recites takbir i.e. `There is no god except Allah') which is mustahabb 6 (desirable, though) ﻻ إﻟﻪ إﻻ اﻟﻠﻪ not obligatory). On entering Mecca, he takes a bath, which is again mustahabb. -

Islamic Studies and Religious Education Bi-Annual Curriculum

Islamic Studies and Religious Education bi-annual Curriculum Subject Leader: Mr Abdullah AS Patel, Deputy Head Teacher Intent We are committed to providing a curriculum with breadth that allows all our pupils to be able to achieve the following: ● Build Islamic character, through the termly topics, and a special focus on character building in the final term. ● To learn relevant knowledge to their religious preferences and the values they come with from home. ● To challenges, motivate, inspire and lead them to a lifelong interest in learning, using their Islamic values as a base for further religious exploration, in further education. ● To facilitate pupils to achieve their personal best and grow up to be Muslims with a strong sense of identity. ● To create a link between different subjects to give the pupils and appreciation of the breadth and connected nature of learning. ● To promote active community involvement, we will ensure pupils are prepared for life in modern Britain, by teaching universal human values, and dedicating time in the year to learning specifically about British Values. Implementation To help us achieve our Islamic Studies curriculum intent, we will: ● Offer a quality-assured curriculum using multiple syllabi, and ensuring all lessons are well-planned and effectively delivered. ● Provide pupils and parents with ‘Tarbiyah’ checklists to monitor their character-building progress. ● Where appropriate, we will provide pupils with the tools to learn more effectively by means of practical demonstrations. ● To build a sense of tolerance and respect, we will arrange trips to visit different places of worship to learn about others and appreciate their teachings. -

Halaman 1 Dari 30 Muka | Daftar

Halaman 1 dari 30 muka | daftar isi Halaman 2 dari 30 muka | daftar isi Halaman 3 dari 30 Perpustakaan Nasional : Katalog Dalam terbitan (KDT) Miqat di Jeddah Tidak Sah? Penulis : Luki Nugroho, Lc 37 hlm ISBN 978-602-1989-1-9 Judul Buku Miqat di Jeddah Tidak Sah? Penulis Luki Nugroho, Lc. MA Editor Fatih Setting & Lay out Fayyad & Fawwaz Desain Cover Faqih Penerbit Rumah Fiqih Publishing Jalan Karet Pedurenan no. 53 Kuningan Setiabudi Jakarta Selatan 12940 Cet : Agustus 2018 muka | daftar isi Halaman 4 dari 30 Daftar Isi Daftar Isi ...................................................................................... 4 A. Permasalahan........................................................................... 7 a. Pangkal Masalah .............................................. 7 b. Perbedaan Pendapat Ulama ............................ 7 B. Pengertian Miqat ...................................................................... 8 1. Bahasa .............................................................. 8 2. Istilah ................................................................ 8 C. Miqat Makani ............................................................................ 9 1. Dzul Hulaifah .................................................. 12 2. Al-Juhfah ........................................................ 15 3. Qarnul Manazil ............................................... 15 4. Yalamlam ........................................................ 16 5. Dzatu ‘Irqin ..................................................... 17 D. Miqat Penumpang -

Textile Arts and Aesthetics in and Beyond the Medieval Islamic World

Perspective Actualité en histoire de l’art 1 | 2016 Textiles Crossroads of Cloth: Textile Arts and Aesthetics in and beyond the Medieval Islamic World Aux carrefours des étoffes : les arts et l’esthétique textiles dans le monde islamique médiéval et au-delà Vera-Simone Schulz Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/perspective/6309 DOI: 10.4000/perspective.6309 ISSN: 2269-7721 Publisher Institut national d'histoire de l'art Printed version Date of publication: 30 June 2016 Number of pages: 93-108 ISBN: 978-2-917902-31-8 ISSN: 1777-7852 Electronic reference Vera-Simone Schulz, « Crossroads of Cloth: Textile Arts and Aesthetics in and beyond the Medieval Islamic World », Perspective [Online], 1 | 2016, Online since 15 June 2017, connection on 01 October 2020. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/perspective/6309 ; DOI : https://doi.org/10.4000/ perspective.6309 Vera-Simone Schulz Crossroads of Cloth: Textile Arts and Aesthetics in and beyond the Medieval Islamic World A piece of woven silk preserved in the Cooper-Hewitt National Design Museum in New York (fig. 1) shows medallions with pearl borders in which various animals appear. The elephants, winged horses, and composite creatures with dog heads and peacock tails are positioned alternately face-to-face and back-to-back. The fabric is designed to be viewed both from a distance and more closely. From a distance, the overall structure with its repeating pattern forms a grid in which geometrical roundels oscillate between contact and isolation. They are so close they seem almost to touch both each other and the complicated vegetal patterns in the spaces between, although in fact each roundel remains separate from every other visual element in the textile. -

Orientation Specification for Mosques

Orientation Specification For Mosques Mohamed Nabeel Tarabishy, Ph.D. Goodsamt, LLC. www.goodsamt.com ABSTRACT: This paper puts a framework for translating religious (Sharia) requirements for turning towards Mecca into geometrical requirements. Another objective of this paper is to investigate the sources of error in finding the direction, and to suggest acceptable limits for the error given the current state of technology without causing undue difficulty. In the process we differentiate between error for individuals and for mosques, and in this work we focus on mosques. Initially, we examined individual perception of direction error. We found it very subjective and would be hard to produce a suitable error limit. Next we used the condition to stay within Mecca as another possible approach to find the limits. Finally, factoring implementation issues, we gave our recommendations for the specs. INTRODUCTION: Turning towards Mecca (Qibla direction) is a prerequisite for a Muslim prayer. While some time the correct direction is not clear, due diligence in finding the Qibla is required. Muslims have turned in the early days of Islam towards Jerusalem, then, they were ordered to turn towards Mecca. Finding the right direction is not a trivial task, it involves the use of coordinate system, and the knowledge of spherical geometry. Such tools enable us to solve the problem easily nowadays, but in the past, people have to resort to different ways to find the Qibla, chief among them is the use of astronomical alignments. These days, it is almost agreed upon that the correct direction is by following the great circle path, however, it is not explained in terms of the requirement of the prayer, and instead it is advocated because it is the shortest distance between the observer and the target (Mecca). -

Download Hajj Guide

In the name of Allah the Beneficent and the Merciful Hajj Guide for Pilgrims With Islamic Rulings (Ahkaam) Philosophy & Supplications (Duaas) SABA Hajj Group Shia-Muslim Association of Bay Area San Jose, California, USA First Edition (Revision 1.1) December, 2003 Second Edition (Revision 2.1) October, 2005 Third Edition (Revision 2.0) December, 2006 Authors & Editors: Hojjatul Islam Dr. Nabi Raza Abidi, Resident Scholar of Shia-Muslim Association of Bay Area Hussnain Gardezi, Haider Ali, Urooj Kazmi, Akber Kazmi, Ali Hasan - Hajj-Guide Committee Reviewers: Hojjatul Islam Zaki Baqri, Hojjatul Islam Sayyed Mojtaba Beheshti, Batool Gardezi, Sayeed Himmati, Muzaffar Khan, and 2003 SABA Hajj Group Hajj Committee: Hojjatul Islam Dr. Nabi Raza Abidi, Syed Mohammad Hussain Muttaqi, Dr. Mohammad Rakhshandehroo, Muzaffar Khan, Haider Ali, Ali Hasan, Sayeed Himmati Copyright Free & Non-Profit Notice: The SABA Hajj Guide can be freely copied, duplicated, reproduced, quoted, distributed, printed, used in derivative works and saved on any media and platform for non-profit and educational purposes only. A fee no higher than the cost of copying may be charged for the material. Note from Hajj Committee: The Publishers and the Authors have made every effort to present the Quranic verses, prophetic and masomeen traditions, their explanations, Islamic rulings from Manasik of Hajj books and the material from the sources referenced in an accurate, complete and clear manner. We ask for forgiveness from Allah (SWT) and the readers if any mistakes have been overlooked during the review process. Contact Information: Any correspondence related to this publication and all notations of errors or omissions should be addressed to Hajj Committee, Shia-Muslim Association of Bay Area at [email protected]. -

Exhibition of Two Holy Mosques Architecture

Exhibition of Two Holy Mosques Architecture النسخة اإلنجليزية Special IssueMakky In the Name of Allah, the Most Gracious, the Most Merciful This issue has been released in cooperation with the General Presidency for the Affairs of the Praise be to Allah, the Lord of all Grand Mosque and the Prophet's Mosque creation, and peace and blessings on the Messenger of Allah -Prophet Mohammad- and on his companions and followers. Dear sons and daughters, With the advent of Islam and for more than 14 centuries, the Two Holy Mosques occupy a special place in the hearts of all Muslims. Serving and caring for these two sacred shrines has always been regarded as a great honor and a sincere act of devotion. History bears witness to the massive architectural achievements and the extended efforts of Muslim rulers since the early Islamic period to restore and renovate these two holy sites. Today, the steps and initiatives taken by our blessed government to maintain and enhance the standards of the facilities and services of the Two Head of the General Presidency for the Holy Mosques are gaining momentum. These endeavors are Affairs of the Grand Mosque and the embraced and fostered by the Custodian of the Two Holy Mosques, His Majesty King Salman ibn Abdulaziz, and His Royal Highness Prophet's Mosque Crown Prince, Mohammad ibn Salman. Their continuous support to Dr. Abdur-Rahman Abdulaziz As-Sudais implement major expansion and development works that combine majestic architecture with modern technology has induced a Deputy Head of Media major shift in the services provided for the visitors of the Two Holy Relations & Affairs Mosques.