Pamela E. Ritchie PHD Thesis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tartan As a Popular Commodity, C.1770-1830. Scottish Historical Review, 95(2), Pp

Tuckett, S. (2016) Reassessing the romance: tartan as a popular commodity, c.1770-1830. Scottish Historical Review, 95(2), pp. 182-202. (doi:10.3366/shr.2016.0295) This is the author’s final accepted version. There may be differences between this version and the published version. You are advised to consult the publisher’s version if you wish to cite from it. http://eprints.gla.ac.uk/112412/ Deposited on: 22 September 2016 Enlighten – Research publications by members of the University of Glasgow http://eprints.gla.ac.uk SALLY TUCKETT Reassessing the Romance: Tartan as a Popular Commodity, c.1770-1830 ABSTRACT Through examining the surviving records of tartan manufacturers, William Wilson & Son of Bannockburn, this article looks at the production and use of tartan in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. While it does not deny the importance of the various meanings and interpretations attached to tartan since the mid-eighteenth century, this article contends that more practical reasons for tartan’s popularity—primarily its functional and aesthetic qualities—merit greater attention. Along with evidence from contemporary newspapers and fashion manuals, this article focuses on evidence from the production and popular consumption of tartan at the turn of the nineteenth century, including its incorporation into fashionable dress and its use beyond the social elite. This article seeks to demonstrate the contemporary understanding of tartan as an attractive and useful commodity. Since the mid-eighteenth century tartan has been subjected to many varied and often confusing interpretations: it has been used as a symbol of loyalty and rebellion, as representing a fading Highland culture and heritage, as a visual reminder of the might of the British Empire, as a marker of social status, and even as a means of highlighting racial difference. -

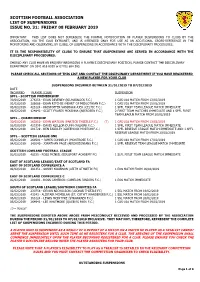

Scottish Football Association List of Suspensions Issue No

SCOTTISH FOOTBALL ASSOCIATION LIST OF SUSPENSIONS ISSUE NO. 31: FRIDAY 08 FEBRUARY 2019 IMPORTANT – THIS LIST DOES NOT SUPERSEDE THE FORMAL NOTIFICATION OF PLAYER SUSPENSIONS TO CLUBS BY THE ASSOCIATION, VIA THE CLUB EXTRANET, AND IS INTENDED ONLY FOR USE AS AN ADDITIONAL CROSS-REFERENCE IN THE MONITORING AND OBSERVING, BY CLUBS, OF SUSPENSIONS IN ACCORDANCE WITH THE DISCIPLINARY PROCEDURES. IT IS THE RESPONSIBILITY OF CLUBS TO ENSURE THAT SUSPENSIONS ARE SERVED IN ACCORDANCE WITH THE DISCIPLINARY PROCEDURES. SHOULD ANY CLUB HAVE AN ENQUIRY REGARDING A PLAYER’S DISCIPLINARY POSITION, PLEASE CONTACT THE DISCIPLINARY DEPARTMENT ON 0141 616 6018 or 07702 864 165. PLEASE CHECK ALL SECTIONS OF THIS LIST AND CONTACT THE DISIPLINARY DEPARTMENT IF YOU HAVE REGISTERED A NEW PLAYER FOR YOUR CLUB SUSPENSIONS INCURRED BETWEEN 31/01/2019 TO 07/02/2019 DATE INCURRED PLAYER (CLUB) SUSPENSION SPFL - SCOTTISH PREMIERSHIP 30/01/2019 276256 - EUAN DEVENEY (KILMARNOCK F.C.) 1 CAS U18 MATCH FROM 13/02/2019 01/02/2019 386086 - DEAN RITCHIE (HEART OF MIDLOTHIAN F.C.) 1 CAS U18 MATCH FROM 15/02/2019 03/02/2019 423124 - KRISTOFFER VASSBAKK AJER (CELTIC F.C.) 1 SPFL FIRST TEAM LEAGUE MATCH IMMEDIATE 06/02/2019 124842 - SCOTT FRASER MCKENNA (ABERDEEN F.C.) 2 FIRST TEAM MATCHES IMMEDIATE AND 1 SPFL FIRST TEAM LEAGUE MATCH FROM 20/02/2019 SPFL – CHAMPIONSHIP 30/01/2019 260210 - DEAN WATSON (PARTICK THISTLE F.C.) (T) 1 CAS U18 MATCH FROM 13/02/2019 02/02/2019 425359 - DAVIS KEILLOR-DUNN (FALKIRK F.C.) 1 SPFL FIRST TEAM LEAGUE MATCH IMMEDIATE 06/02/2019 201729 - BEN -

Form Foreign Policy Took- Somerset and His Aims: Powers Change? Sought to Continue War with Scotland, in Hope of a Marriage Between Edward and Mary, Queen of Scots

Themes: How did relations with foreign Form foreign policy took- Somerset and his aims: powers change? Sought to continue war with Scotland, in hope of a marriage between Edward and Mary, Queen of Scots. Charles V up to 1551: The campaign against the Scots had been conducted by Somerset from 1544. Charles V unchallenged position in The ‘auld alliance’ between Franc and Scotland remained, and English fears would continue to be west since death of Francis I in dominated by the prospect of facing war on two fronts. 1547. Somerset defeated Scots at Battle of Pinkie in September 1547. Too expensive to garrison 25 border Charles won victory against forts (£200,000 a year) and failed to prevent French from relieving Edinburgh with 10,000 troops. Protestant princes of Germany at In July 1548, the French took Mary to France and married her to French heir. Battle of Muhlberg, 1547. 1549- England threatened with a French invasion. France declares war on England. August- French Ottomans turned attention to attacked Boulogne. attacking Persia. 1549- ratified the Anglo-Imperial alliance with Charles V, which was a show of friendship. Charles V from 1551-1555: October 1549- Somerset fell from power. In the west, Henry II captured Imperial towns of Metz, Toul and Verdun and attacked Charles in the Form foreign policy-Northumberland and his aims: Netherlands. 1550- negotiated a settlement with French. Treaty of In Central Europe, German princes Somerset and Boulogne. Ended war, Boulogne returned in exchange for had allied with Henry II and drove Northumberland 400,000 crowns. England pulled troops out of Scotland. -

Christopher Upton Phd Thesis

?@A374? 7; ?2<@@7?6 81@7; 2IQJRSOPIFQ 1$ APSON 1 @IFRJR ?TCMJSSFE GOQ SIF 3FHQFF OG =I3 BS SIF ANJUFQRJSX OG ?S$ 1NEQFVR '.-+ 5TLL MFSBEBSB GOQ SIJR JSFM JR BUBJLBCLF JN >FRFBQDI0?S1NEQFVR/5TLL@FWS BS/ ISSP/%%QFRFBQDI#QFPORJSOQX$RS#BNEQFVR$BD$TK% =LFBRF TRF SIJR JEFNSJGJFQ SO DJSF OQ LJNK SO SIJR JSFM/ ISSP/%%IEL$IBNELF$NFS%'&&()%(,)* @IJR JSFM JR PQOSFDSFE CX OQJHJNBL DOPXQJHIS STUDIES IN SCOTTISH LATIN by Christopher A. Upton Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at the University of St. Andrews October 1984 ýýFCA ýý£ s'i ý`q. q DRE N.6 - Parentibus meis conjugique meae. Iý Christopher Allan Upton hereby certify that this thesis which is approximately 100,000 words in length has been written by men that it is the record of work carried out by me and that it has not been submitted in any previous application for a higher degree. ý.. 'C) : %6 date .... .... signature of candidat 1404100 I was admitted as a research student under Ordinance No. 12 on I October 1977 and as a candidate for the degree of Ph. D. on I October 1978; the higher study for which this is a record was carried out in the University of St Andrews between 1977 and 1980. $'ý.... date . .. 0&0.9 0. signature of candidat I hereby certify that the candidate has fulfilled the conditions of the Resolution and Regulations appropriate to the degree of Ph. D. of the University of St Andrews and that he is qualified to submit this thesis in application for that degree. -

The Scottish Genealogist

THE SCOTTISH GENEALOGY SOCIETY THE SCOTTISH GENEALOGIST INDEX TO VOLUMES LIX-LXI 2012-2014 Published by The Scottish Genealogy Society The Index covers the years 2012-2014 Volumes LIX-LXI Compiled by D.R. Torrance 2015 The Scottish Genealogy Society – ISSN 0330 337X Contents Please click on the subject to be visited. ADDITIONS TO THE LIBRARY APPRECIATIONS ARTICLE TITLES BOOKMARKS BOOK REVIEWS CONTRIBUTORS FAMILY TREES GENERAL INDEX ILLUSTRATIONS INTRODUCTION QUERIES INTRODUCTION Where a personal or place name is mentioned several times in an article, only the first mention is indexed. LIX, LX, LXI = Volume number i. ii. iii. iv = Part number 1- = page number ; - separates part numbers within the same volume : - separates volume numbers BOOKMARKS The contents of this CD have been bookmarked. Select the second icon down at the left-hand side of the document. Use the + to expand a section and the – to reduce the selection. If this icon is not visible go to View > Show/Hide > Navigation Panes > Bookmarks. Recent Additions to the Library (compiled by Joan Keen & Eileen Elder) LIX.i.43; ii.102; iii.154: LX.i.48; ii.97; iii.144; iv.188: LXI.i.33; ii.77; iii.114; Appreciations 2012-2014 Ainslie, Fred LIX.i.46 Ferguson, Joan Primrose Scott LX.iv.173 Hampton, Nettie LIX.ii.67 Willsher, Betty LIX.iv.205 Article Titles 2012-2014 A Call to Clan Shaw LIX.iii.145; iv.188 A Case of Adultery in Roslin Parish, Midlothian LXI.iv.127 A Knight in Newhaven: Sir Alexander Morrison (1799-1866) LXI.i.3 A New online Medical Database (Royal College of Physicians) -

The History of Scotland from the Accession of Alexander III. to The

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA AT LOS ANGELES THE GIFT OF MAY TREAT MORRISON IN MEMORY OF ALEXANDER F MORRISON THE A 1C MEMORIAL LIBRARY HISTORY OF THE HISTORY OF SCOTLAND, ACCESSION OF ALEXANDEB III. TO THE UNION. BY PATRICK FRASER TYTLER, ** F.RS.E. AND F.A.S. NEW EDITION. IN TEN VOLUMES. VOL. X. EDINBURGH: WILLIAM P. NIMMO. 1866. MUEKAY AND OIBB, PUINTERS. EDI.VBUKOII V.IC INDE X. ABBOT of Unreason, vi. 64 ABELARD, ii. 291 ABERBROTHOC, i. 318, 321 ; ii. 205, 207, 230 Henry, Abbot of, i. 99, Abbots of, ii. 206 Abbey of, ii. 205. See ARBROATH ABERCORN. Edward I. of England proceeds to, i. 147 Castle of, taken by James II. iv. 102, 104. Mentioned, 105 ABERCROMBY, author of the Martial Achievements, noticed, i. 125 n.; iv. 278 David, Dean of Aberdeen, iv. 264 ABERDEEN. Edward I. of England passes through, i. 105. Noticed, 174. Part of Wallace's body sent to, 186. Mentioned, 208; ii. Ill, n. iii. 148 iv. 206, 233 234, 237, 238, 248, 295, 364 ; 64, ; 159, v. vi. vii. 267 ; 9, 25, 30, 174, 219, 241 ; 175, 263, 265, 266 ; 278, viii. 339 ; 12 n.; ix. 14, 25, 26, 39, 75, 146, 152, 153, 154, 167, 233-234 iii. Bishop of, noticed, 76 ; iv. 137, 178, 206, 261, 290 ; v. 115, n. n. vi. 145, 149, 153, 155, 156, 167, 204, 205 242 ; 207 Thomas, bishop of, iv. 130 Provost of, vii. 164 n. Burgesses of, hanged by order of Wallace, i. 127 Breviary of, v. 36 n. Castle of, taken by Bruce, i. -

Victorian Representations of Mary, Queen of Scots and Elizabeth I

College of Saint Benedict and Saint John's University DigitalCommons@CSB/SJU Honors Theses, 1963-2015 Honors Program 2015 Victorian Representations of Mary, Queen of Scots and Elizabeth I Grace K. Butkowski College of Saint Benedict/Saint John's University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.csbsju.edu/honors_theses Part of the European History Commons, Political History Commons, and the Women's History Commons Recommended Citation Butkowski, Grace K., "Victorian Representations of Mary, Queen of Scots and Elizabeth I" (2015). Honors Theses, 1963-2015. 69. https://digitalcommons.csbsju.edu/honors_theses/69 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@CSB/SJU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses, 1963-2015 by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@CSB/SJU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Grace Butkowski Victorian Representations of Mary, Queen of Scots and Elizabeth I The rivalry of Mary, Queen of Scots and her English cousin Elizabeth I is a storied one that has consumed both popular and historical imaginations since the two queens reigned in the sixteenth century. It is often portrayed as a tale of contrasts: on one end, Gloriana with her fabled red hair and virginity, the bastion of British culture and Protestant values, valiantly defending England against the schemes of the Spanish and their Armada. On the other side is Mary, Queen of Scots, the enchanting and seductive French-raised Catholic, whose series of tragic, murderous marriages gave birth to both the future James I of England and to schemes surrounding the English throne. -

Copyrighted Material

33_056819 bindex.qxp 11/3/06 11:01 AM Page 363 Index fighting the Vikings, 52–54 • A • as law-giver, 57–58 Aberfan tragedy, 304–305 literary interests, 56–57 Act of Union (1707), 2, 251 reforms of, 54–55 Adelaide of Saxe-Meiningen, queen of reign of, 50, 51–52 William IV, 268, 361 Alfred, son of King Aethelred, king of Áed, king of Scotland, 159 England, 73, 74 Áed Findliath, ruler in Ireland, 159 Ambrosius Aurelianus (Roman leader), 40 Aedán mac Gabráin, overking of Dalriada, 153 Andrew, Prince, Duke of York (son of Aelfflaed, queen of Edward, king Elizabeth II) of Wessex, 59 birth of, 301 Aelfgifu of Northampton, queen of Cnut, 68 as naval officer, 33 Aethelbald, king of Mercia, 45 response to death of Princess Diana, 313 Aethelbert, king of Wessex, 49 separation from Sarah, Duchess of York, Aethelflaed, daughter of Alfred, king of 309 Wessex, 46 Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, 57, 58, 63 Aethelfrith, Saxon king, 43 Anglo-Saxons Aethelred, king of England, 51, 65–66 appointing an heir, 16 Aethelred, king of Mercia, 45, 46, 55 invasion of Britain, 39–41 Aethelred, king of Wessex, 50 kingdoms of, 37, 42 Aethelstan, king of Wessex, 51, 61–62 kings of, 41–42 Aethelwold, son of Aethelred, king of overview, 12 Wessex, 60 Anna, queen of Scotland, 204 Aethelwulf, king of Wessex, 49 Anne, Princess Royal, daughter of Africa, as part of British empire, 14 Elizabeth II, 301, 309 Agincourt, battle of, 136–138 Anne, queen of England Albert, Prince, son of George V, later lack of heir, 17 George VI, 283, 291 marriage to George of Denmark, 360–361 Albert of -

James I Biography

JAMES I OF ENGLAND (JAMES IV OF SCOTLAND) 1566-1625 1566 (June 19) Born at Edinburgh Castle, only son of Mary, Queen of Scots and Lord Darnley (Henry Stuart), grandson of Margaret Tudor (Hen VIII sister) 1566 (March 9) David Rizzio, Mary’s private secretary, murdered in the presence of Queen Mary, by a group that included Darnley 1567 (Feb. 10) explosion in the night, Darnley found dead at Kirk O’Field, Edinburgh 1567 (June) Mary imprisoned by Protestant rebels; forced to abdicate. 1567 (July 29) James, 13 mos, crowned King of Scots; coronation sermon John Knox 1568 Mary escaped; her troops defeated at the Battle of Langside, fled to England; Elizabeth, Elizabeth's "guest" for next 19 years. They never meet. 1582 James imprisoned in Ruthven castle for 10 months by Protestant earls due to James’ close (intimate?) relationship with the Catholic Duke of Lennox 1583 (June) James freed, reestablished his royal authority 1586 Signed the Treaty of Berwick with England; securing English succession. 1587 Mary, Queen of Scots executed by Elizabeth I, James now Eliz' successor. 1589 Married Anne of Denmark, age 14; seven live children, three grow to adulthood. 1597 Wrote Daemonologie, the basis for Shakespeare’s Tragedy of Macbeth 1603 (March 24) Queen Elizabeth dies; James proclaimed king in London. 1604 (October) Assumed the title “King of Great Britain” 1605 Gunpowder Plot; Catholic Guy Fawkes & others try to blow up whole Parliament. 1611 Completion of the Authorized King James Version of the Bible. (James planned) 1612 death of Prince of wales, Henry. Now Charles becomes successor. -

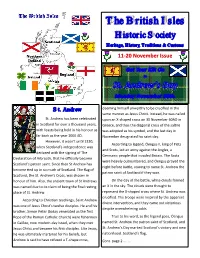

11-20 November Issue

The British Isles Historic Society Heritage, History, Traditions & Customs 11-20 November Issue St. Andrew deeming himself unworthy to be crucified in the same manner as Jesus Christ. Instead, he was nailed St. Andrew has been celebrated upon an X-shaped cross on 30 November 60AD in in Scotland for over a thousand years, Greece, and thus the diagonal cross of the saltire with feasts being held in his honour as was adopted as his symbol, and the last day in far back as the year 1000 AD. November designated his saint day. However, it wasn’t until 1320, According to legend, Óengus II, king of Picts when Scotland’s independence was and Scots, led an army against the Angles, a declared with the signing of The Germanic people that invaded Britain. The Scots Declaration of Arbroath, that he officially became were heavily outnumbered, and Óengus prayed the Scotland’s patron saint. Since then St Andrew has night before battle, vowing to name St. Andrew the become tied up in so much of Scotland. The flag of patron saint of Scotland if they won. Scotland, the St. Andrew’s Cross, was chosen in honour of him. Also, the ancient town of St Andrews On the day of the battle, white clouds formed was named due to its claim of being the final resting an X in the sky. The clouds were thought to place of St. Andrew. represent the X-shaped cross where St. Andrew was crucified. The troops were inspired by the apparent According to Christian teachings, Saint Andrew divine intervention, and they came out victorious was one of Jesus Christ’s twelve disciples. -

Van Heijnsbergen, T. (2013) Coteries, Commendatory Verse and Jacobean Poetics: William Fowler's Triumphs of Petrarke and Its Castalian Circles

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Enlighten: Publications Van Heijnsbergen, T. (2013) Coteries, commendatory verse and Jacobean poetics: William Fowler's triumphs of Petrarke and its Castalian circles. In: Parkinson, D.J. (ed.) James VI and I, Literature and Scotland: Tides of Change, 1567-1625. Peeters Publishers, Leuven, Belgium, pp. 45- 63. ISBN 9789042926912 Copyright © 2013 Peeters Publishers A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge Content must not be changed in any way or reproduced in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holder(s) When referring to this work, full bibliographic details must be given http://eprints.gla.ac.uk/69695/ Deposited on: 23 September 2013 Enlighten – Research publications by members of the University of Glasgow http://eprints.gla.ac.uk James VI and I, Literature and Scotland Tides of Change, 1567-1625 EDITED BY David J. Parkinson PEETERS LEUVEN - PARIS - WALPOLE, MA 2013 CONTENTS Plates vii Abbreviations vii Note on Orthography, Dates and Currency vii Preface and Acknowledgements ix Introduction David J. Parkinson xi Contributors xv Shifts and Continuities in the Scottish Royal Court, 1580-1603 Amy L. Juhala 1 Italian Influences at the Court of James VI: The Case of William Fowler Alessandra Petrina 27 Coteries, Commendatory Verse and Jacobean Poetics: William Fowler's Trivmphs of Petrarke and its Castalian Circles Theo van Heijnsbergen 45 The Maitland -

Download Touring Itinerary

Touring Itinerary (1-3 days) TRAVEL TRADE Love East Lothian Tantallon Castle Highlights of East Lothian Suggested options for a one to three day tour of Edinburgh’s Coast and Countryside. With its rich history and ancient castles, famous Scots and Scotland’s industrial past there are plenty of themes to be followed in glorious East Lothian with its contrasting coastal and hilly landscapes. From whatever base whether from Edinburgh, centred in the region or coming up from the south, there’s scope to create a whole vacation in the region or equally combine with Scotland wide options. Ideal for groups and also independent traveller options. Inveresk Lodge and Gardens visiteastlothian.org TRAVEL TRADE Day One Castles and Coastal Life Day Two National Treasures & Natural Places Following the East Lothian Coastal route (A198), Boat trips from North Berwick and Dunbar Suggest starting the day at the National Museum Scenic walk ideas a road mostly along the coast with fine views, of Flight and combine with some of the region’s Coastal/ Wildlife / Activities/ Environment For walks, great views and historical landmarks there are many landmarks to visit. best countryside, natural places and hidden gems. consider Dunbar’s historic harbours, there are 3, A number of little islands are dotted around this For interest in following the footsteps of John with Dunbar Castle ruins; the Battery or the cliff- Mix and match heritage visits, boat trips, seaside coastline – Fidra, the acclaimed inspiration for Muir, the famous Naturalist then Dunbar is the top walk and East Beach. towns and beaches along with great food stops.