How Does Exposure to the Internet Affect Political Knowledge and Attitudes Among Rural Chinese?: a Field Experiment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

8Th Textile Bioengineering and Informatics Symposium Proceedings (TBIS 2015)

8th Textile Bioengineering and Informatics Symposium Proceedings (TBIS 2015) Zadar, Croatia 14 - 17 June 2015 Editors: Yi Li Budimir Mijovic Jia-Shen Li ISBN: 978-1-5108-1325-0 Printed from e-media with permission by: Curran Associates, Inc. 57 Morehouse Lane Red Hook, NY 12571 Some format issues inherent in the e-media version may also appear in this print version. Copyright© (2015) by Textile Bioengineering and Informatics Society (TBIS) All rights reserved. Printed by Curran Associates, Inc. (2016) For permission requests, please contact Textile Bioengineering and Informatics Society (TBIS) at the address below. Textile Bioengineering and Informatics Society (TBIS) Hong Kong Polytechnic University ST733 Hung Hom, Hong Kong Phone: (852) 9771 6139, 2766 6479 Fax: (852) 2764 5489 [email protected] Additional copies of this publication are available from: Curran Associates, Inc. 57 Morehouse Lane Red Hook, NY 12571 USA Phone: 845-758-0400 Fax: 845-758-2633 Email: [email protected] Web: www.proceedings.com PROCEEDINGS OF TBIS 2015 TABLE OF CONTENT Track 1 Textile Material Bioengineering 1 Preparation and Mechanical Characterization of Luffa Fibre Reinforced Low Density Polyethylene Composites Levent Onal, Yekta Karaduman, Cagrialp Arslan 1 2 Optimum Pyrolysis of Waste Acrylic Fibers for Preparation of Activated Carbon Vijay Baheti, Salman Naeem, Jiri Militky, Rajesh Mishra, Blanka Tomkova 7 3 Study on Comfort of Knitted Fabric Blended with PTT Fibers Xiu-E Bai, Xiao-Yu Han, Dong-Yan Wu, Ling Chen, Wei Wang 1 5 4 New Approach to Yarn -

Lime Rock Gazette : October 31, 1850

A S A M 1 O «F WO i■W' f H (WT A TL I f t l R A T O B B VOLUME V. ROCKLAND, MAINE, THURSDAY MORNING, OCTOBER 31. 1850. NUMBER XL. T H E D E M O N B R I D E . about 20 men lying immovable on the flat of tied to splash and plunge, nnd blow, nnd make CHOOSING A HUSBAND. l.u t us now lorn to Isabel. Bail as rep.ort T H E M U S E . ------ 1 their stomachs in solemn silence anil with her circular course, varying me along with her made her husband it did not tell half tlio i l ’ oetry is the silver setting of golden thought, “ >nta Bena, the \c iv Orleans correspondent of their heads buried in blankets. Presently they ns if I wits a fly nil her tail. Finding Iter tail The following story undertakes to it,form the j truth. Stanley now spent tlirp.e-fuurtbs of the Concordia( oneortlin IntclIntcll.cen 1 igeaeer,eer. hiin hisIds lastlast, lcttciletter. rniged ,|len)gl.|vcg ,,,, on n,| rnlirg gave me Imt a poor hold, as the only means o f girls nbout soniellting we presume they under-| |,is :j,ne in the city, anil during the other copies the report which appeared in the Ti ne securing my prey, I took out my knife, and stand in all its pros and nnu,—its d ifliru liit fourth, when he was at home, was morose to Delta, of the case of n man who Was nttcinptcd mninetl with their bodies halanecd in mill nir ntul emharassinents, full ns well ns our good Death of the Flowers. -

M!'SS! J Try Pots, Pic Nic Baskets, No Do Dat, So It No Vunder Be Git Torso." 11 AC LL

" " ' " " - - , .... HONOLULU, H. I., III MAY 5, 1855. No. 5-- 2 FOX.7NSSIAN BUSINESS CARDS. - BUSINESS. CARDS. GENERAL safes, t- PUBLISHED WEEKLY AT HO.VOLULIT, OAHl, B. I. MERCHANDISE. vaults, tronka not otherwise provided (or, vin Sc. egr, wax, sperm, Hack-fis- h EDWIN O. HALL, EDITOR. WHOLESALE RETAIL. fJnlnnesian. whale, seal, porpoise and BANS OF oil, neatsfoot and cocoanut oils, marblies;--lead- , ' I TerMb r - WILLIAM BOW DEN, Be F. s our lead-pip- e, lines, nets, grind stones, grasw, hr.pt 6 0 PAGE, BACON m SALE ita large assortment of Od copy bbbbbj, ia advaaea, Ship Broker and General Agent? 3 & CO., - ttri.na rOR HEW AOT. live stock not otherwise Pr BKMUbn, .3 50 a- TARIFF enumerated; slate, milder, cup; ix " tf--2 Merchandise, comprising in part the folio wine sand-pape- r, Oa. - w es c llleaalala. Fart Si. 1 . - The following ia the new tariff act passed by spy-glass- and wk.-ry- 3igle eopia., 12J HONOLULU. nusea articles : telesTcfpes Drafts all kinds, Orleans, Alpacca, Alepine, BaK .Hate af Adrertiaia. , , FELDIIEIM & CO., bought on the principal cities of the TJni - DRY GOODS. the House of Representatives on the 28U ult. and bnn Importers ted States England, Cases colors zorine, manufacture of worsted ot Oaqire, (Nltlaes) im insert io, $1 CO. and Commission Merchants, and also stent Exchanfr- - txr ass'd prints, do figured do, on the 3d May by the House of Nobles: or Cashmere, or each eoatiauance, 45 Qarea at.. Haaalala. Oaha, S. I. 25-t- f sale in suras to suit. Do orange striped do, do jaconet muslin, which they shall be a component cart, not Hitf " (3liBerlaa) nratiaaertioB,,.....,.,, 50 Wr. -

Friends of the Museums Singapore January / February 2018 Art History

Friends of the Museums Singapore January / February 2018 art history culture people President's Letter Dear Friends, Happy New Year! This year, FOM celebrates its 40th birthday. It is also the 10th anniversary of PASSAGE magazine. The new council is gearing up to celebrate these twin anniversaries with exciting programmes and limited-edition merchandise. So do check our website, Facebook and newsletters regularly for updates. Since its creation 40 years ago, FOM has grown from strength to strength. From providing guiding services to one museum in 1980, its docents now guide in nine museums, art and heritage institutions. And from just 100 members in 1978, its membership reached 1,500 last year. The society has evolved over the years to meet the changing needs of our members with new programmes such as photography workshops, cooking classes and foodie groups. It has been no mean feat for an entirely volunteer-run society to have continued to serve the museum community in Singapore and its own members with passion and enthusiasm over such a long span of time. FOM could not have done all this without the selfless contributions of time and energy of our volunteers, FOM’s heart and soul. PASSAGE itself has also evolved. The magazine started life as a no-frills newsletter printed on cyclostyled paper with content meant solely for the FOM community. In September 2008, the first full-colour issue of PASSAGE was officially launched, replacing the newsletter. Thanks to Andra Leo, the managing editor of PASSAGE, and her editorial team, we now have a beautiful magazine with articles that appeal to the wider community. -

Sent-Down Body‖ Remembers: Contemporary Chinese Immigrant Women‘S Visual and Literary Narratives

The ―Sent-Down Body‖ Remembers: Contemporary Chinese Immigrant Women‘s Visual and Literary Narratives Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Dong Li Isbister, M.A. Graduate Program in Women‘s Studies. The Ohio State University 2009 Dissertation Committee: Linda Mizejewski, Advisor Sally Kitch, Co-advisor Rebecca Wanzo Judy Wu Copyright by Dong Li Isbister 2009 Abstract In this dissertation, I use contemporary Chinese immigrant women‘s visual and literary narratives to examine gender, race, ethnicity, migration, immigration, and sexual experiences in various power discourses from a transnational perspective. In particular, I focus on the relationship between body memories and history, culture, migration and immigration portrayed in these works. I develop and define ―the sent-down body,‖ a term that describes educated Chinese urban youths (also called sent-down youths in many studies) working in the countryside during the Chinese Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution (1966-1976). The ―sent-down body‖ in this context and in my analysis is the politicized and sexualized migrant body. The term also describes previous sent-down youths‘ immigration experiences in the United States, because many of them became immigrants in the post-Cultural Revolution era and are usually described as ―overseas sent-down youths‖ (yangchadui). Therefore, the ―sent-down body‖ is also the immigrant body, and it is racialized. Moreover, the ―sent-down body‖ is gendered, but I study the female ―sent-down body‖ and its represented experiences in specific political, historical, cultural, and sexual contexts. By using ―the sent-down body‖ as an organizing concept in my dissertation, I introduce a new category of analysis in studies of Chinese immigrants‘ history and culture. -

Journeys Along the Seventh Ring

Follow us on WeChat Now Advertising Hotline 400 820 8428 城市漫步北京 英文版 10 月份 国内统一刊号: CN 11-5232/GO China Intercontinental Press ISSN 1672-8025 Journeys Along OCTOBER 2014 the Seventh Ring 主管单位 :中华人民共和国国务院新闻办公室 Supervised by the State Council Information Office of the People's Republic of China 主办单位 :五洲传播出版社 地址 :北京市海淀区北三环中路31 号生产力大楼 B 座 602 邮编 100088 工体店 GONG TI STORE 麦子店 MAI ZI DIAN STORE B-602 Shengchanli Building, No. 31 Beisanhuan Zhonglu, First floor of Lianbao Flat, Middle 104, No.15 Zaoying Beli, Maizidian Xingfu Street, Chaoyang District, Street, Chaoyang District, Beijing Haidian District, Beijing 100088, PRC Beijing 朝阳区麦子店枣营北里 15 号 104 号 http://www.cicc.org.cn 朝阳区幸福中路联宝公寓一层 AM 8:00-PM22:00 TEL:65076361 社长 President of China Intercontinental Press 李红杰 Li Hongjie AM 8:00-PM 24:00 TEL:64177970 期刊部负责人 Supervisor of Magazine Department 邓锦辉 Deng Jinhui 三里屯店 SAN LI TUN STORE 丽都店 LIDO STORE No.1 Sanlitun Beixiaojie, Chaoyang No.102 The Richmond Park District, Beijing Editor-in-Chief Stephen George LeisureCenter, Fangyuan South Street, 朝阳区三里屯北小街 1 号 Senior Editors Oscar Holland, Will Philipps, Chaoyang District, Beijing AM 8:00-PM21:00 TEL:84551245 Karoline Kan, Marianna Cerini 朝阳区芳园南路丽都水岸会所 102 号 AM 8:00-PM22:00 TEL:84578116 乐成国际店 LANDGENT Arts Editor Andrew Chin INTERNATIONAL STORE Nightlife Editor Alex Taggart 公园大道店 PARK AVENUE STORE No.76 Landgent International 5-2 Online Editor Nona Tepper No.111 Shopping Complex,No.6 Baiziwan South Erlu, Chaoyang District, Staff Reporter Stan Aron Chaoyang Park South Road, Chaoyang Beijing District, -

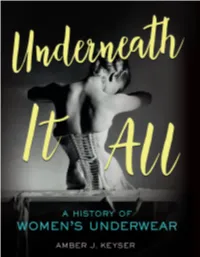

Amber J. Keyser

Did you know that the world’s first bra dates to the fifteenth century? Or that wearing a nineteenth-century cage crinoline was like having a giant birdcage strapped around your waist? Did you know that women during WWI donated the steel stays from their corsets to build battleships? For most of human history, the garments women wore under their clothes were hidden. The earliest underwear provided warmth and protection. But eventually, women’s undergarments became complex structures designed to shape their bodies to fit the fashion ideals of the time. When wide hips were in style, they wore wicker panniers under their skirts. When narrow waists were popular, women laced into corsets that cinched their ribs and took their breath away. In the modern era, undergarments are out in the open. From the designer corsets Madonna wore on stage to Beyoncé’s pregnancy announcement on Instagram, lingerie is part of everyday wear, high fashion, fine art, and innovative technological advances. This feminist exploration of women’s underwear— with a nod to codpieces, tighty- whities, and boxer shorts along the way—reveals the intimate role lingerie plays in defining women’s bodies, sexuality, gender identity, and body image. It is a story of control and restraint but also female empowerment and self- expression. You will never look at underwear the same way again. REINFORCED BINDING AMBER J. KEYSER TWENTY-FIRST CENTURY BOOKS / MINNEAPOLIS For Lacy, who puts the voom in va-va-voom Cover photograph: Photographer Horst P. Horst took this image of a Mainbocher corset in 1939. It is one of the most iconic photos of fashion photography. -

“Public” Women: Commercialized Performance, Nation-Building, and Actresses’ Strategies in Early Twentieth-Century Beijing

The Use Of “Public” Women: Commercialized Performance, Nation-Building, And Actresses’ Strategies In Early Twentieth-Century Beijing by Weikun Cheng Working Paper #275 June 2002 Abstract In the male-dominated theatrical world, actresses strategically relied on personal connections to survive. As “public” women and agents of mass media, they were utilized by men for different purposes. Theatrical managers and male audiences were intent to turn actresses into sexual objects in licentious plays, whereas nationalist reformers recruited actresses for mass mobilization. Actresses participated in the nation-building cause through presenting diverse human roles whose stories conveyed either new ideologies or historical values. The fictional plots of women’s emancipation, however, provided a learning process in which actresses could adopt the concepts of personal rights, self-determined marriage, and economic autonomy. The Chinese state, despite minor variations, always sustained the ideals of gender distinctions and opposed or restrained women’s public roles. The stories of actresses’ survival and prosperity nonetheless demonstrated the tremendous endurance, flexibility, intelligence, and strength of Chinese women. About the Author Weikun Cheng, an Asian historian, currently teaches at California State University, Chico. His major research interest is women in urban public space in modern China. Among his publications are “Going Public through Education” (Late Imperial China, vol. 21, no. 1, 2000) and “The Challenge of the Actresses” (Modern China, vol. 22, no. 2, 1996). Now he is completing a book manuscript entitled “Beyond Home: Women’s Rituals, Work, Leisure, Communities, and Feminist Activism in the Public Space of Early Twentieth-Century Beijing” which is to be published by the University Press of America. -

Fashioning Change: the Cultural Economy of Clothing In

FASHIONING CHANGE: THE CULTURAL ECONOMY OF CLOTHING IN CONTEMPORARY CHINA by Jianhua (Andrew) Zhao B.A., Wuhan University of Hydro-Electric Engineering, 1997 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Pittsburgh 2008 UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH SCHOOL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES This dissertation was presented by Jianhua (Andrew) Zhao It was defended on April 18, 2008 and approved by Dr. Joseph Alter, Professor, Department of Anthropology Dr. Evelyn Rawski, University Professor, Department of History Dr. Harry Sanabria, Associate Professor, Department of Anthropology Dr. Andrew Strathern, Mellon Professor, Department of Anthropology Dissertation Advisor: Dr. Nicole Constable, Professor, Department of Anthropology ii Copyright © by Jianhua (Andrew) Zhao 2008 iii FASHIONING CHANGE: THE CULTURAL ECONOMY OF CLOTHING IN CONTEMPORARY CHINA Jianhua (Andrew) Zhao, PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2008 This dissertation is based on fifteen months of field research in Shanghai and Beijing conducted in 2002 and 2004. The central question with which this dissertation is concerned is how clothing and the clothing industry is constituted by and constitutive of the phenomenal changes that have taken place in contemporary China, especially in the post-1978 reform period. Specifically, this dissertation addresses two major questions: 1) Are the changes in Chinese clothing and the clothing industry merely a part of China’s economic development or modernization? And 2) does China’s integration with the global economy translate into a Westernization of China? The development of China’s textile and apparel industries is a process of liberalization in which the socialist state cultivates and encourages market competition in China’s economy. -

Fashion Localisation in a Global Aesthetic Market

This may be the author’s version of a work that was submitted/accepted for publication in the following source: Ferrero-Regis, Tiziana (2011) Fashion localisation in a global aesthetic market. In 2nd Annual International Conference of Popular Culture Association of Australia and New Zealand (POPCAANZ), 2011-06-20 - 2011-07-02. (Un- published) This file was downloaded from: https://eprints.qut.edu.au/47357/ c Copyright 2011 Tiziana Ferrero-Regis This work is covered by copyright. Unless the document is being made available under a Creative Commons Licence, you must assume that re-use is limited to personal use and that permission from the copyright owner must be obtained for all other uses. If the docu- ment is available under a Creative Commons License (or other specified license) then refer to the Licence for details of permitted re-use. It is a condition of access that users recog- nise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. If you believe that this work infringes copyright please provide details by email to [email protected] Notice: Please note that this document may not be the Version of Record (i.e. published version) of the work. Author manuscript versions (as Sub- mitted for peer review or as Accepted for publication after peer review) can be identified by an absence of publisher branding and/or typeset appear- ance. If there is any doubt, please refer to the published source. http:// popcaanz.com/ Fashion localisation in a global aesthetic market Dr Tiziana Ferrero-Regis, Queensland University of Technology, Brisbane This paper investigates how fashion circulates globally and is adapted and localised by consumers. -

A Glossary of Words and Phrases in the Oral Performing and Dramatic

Yuan dynasty fresco of a dramatic performance, dated 1324. Preserved in the Shuishen Monastery attached to the Guangsheng Temple in Hongdong, Shanxi Province. Source: Yuanren zaju zhu, edited by Yang Jialuo, Taipei: Shijieshuju, 1961 A GLOSSARY OF WORDS AND PHRASES IN THE ORAL PERFORMING AND DRAMATIC LITERATURES OF THE JIN, YUAN, AND MING by DALE R. JOHNSON CENTER FOR CHINESE STUDIES THE UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN ANN ARBOR Open access edition funded by the National Endowment for the Humanities/ Andrew W. Mellon Foundation Humanities Open Book Program. Michigan Monographs in Chinese Studies Series Established 1968 Published by Center for Chinese Studies The University of Michigan Ann Arbor, Michigan 48104-1608 © 2000 The Regents of the University of Michigan © The paper used in this publication meets the requirements of the American National Standard for Information Sciences—Permanence of Paper for Publications and Documents in Libraries and Archives ANSI/NISO/Z39.48—1992. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Johnson, Dale R. A glossary of words and phrases in the oral performing and dramatic literatures of the Jin, Yuan, and Ming = [Chin Yuan Ming chiang ch'ang yii hsi chu wen hsueh tz'u hui] / Dale R. Johnson, p. cm.—(Michigan monographs in Chinese studies, ISSN 1080-9053 ; 89) Parallel title in Chinese characters. Includes bibliographical references. ISBN 0-89264- 138-X 1. Chinese drama-960-1644—Dictionaries-Chinese. 2. Folk literature, Chinese—Dictionaries-Chinese. 3. Chinese language—Dictionaries- English. I. Title: [Chin -

NEXT MEETING at MAINGATE LAKESIDE RESORT January 9

A Florida social and Support Group for TG’s and Their spouses/partners. Located in Central Florida Volume 29 January 2016 Number 1 NEXT MEETING at MAINGATE LAKESIDE RESORT January 9, 2016 Changing room opens at 4:30PM , Auction at 7:00PM+ FEM mailing Address FEM Board of Directors Volunteers President: Carolyn Interviews Sheila Phi Epsilon Mu Vice President: Lynn Interviews Carolyn P.O. Box 158 Treasurer: Jessica GNO Coord. Jessica & Denise Highland City Newsletter Editor: Darlene Photographer Laura FL 33846-0158 Librarian: Jennifer Web Chief Desiree & Stephan Director at Large Dee Social Activities Darlene Chapter Web Page Director at Large Stephanie Social Activities Open http:// crossdressflorida.com/ meeting dinner out at a local restaurant. So, as we enter 2016, Thanks go out to Jessica, Dar- lene, Dee, Lynn, Linda, , Sheila, Jennifer, and Desiree for all they did serving the group in 2015. Thanks also must go to all the ladies who pitched in and helped out whenever it was needed. It sure seemed to me that any time help was re- quested, someone’s hand went right up. The fact is, I’m too darn lazy to go back through all my notes and all the newsletters to see just who did what, so please know that all each of you did was appreciated by many more than just me. 2016 will bring some changes. Our official GNO’s will move to Saturday’s with dinner begin- ning around 4:00 to 4:30 at one of several nearby restaurants. Social hour begins by 6:00, and the official business meeting at 7:30.