The Way to the 1930S' Shanghai Female Stardom

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Yuan Muzhi Y La Comedia Modernista De Shanghai

Yuan Muzhi y la comedia modernista de Shanghai Ricard Planas Penadés ------------------------------------------------------------------ TESIS DOCTORAL UPF / Año 2019 Director de tesis Dr. Manel Ollé Rodríguez Departamento de Humanidades Als meus pares, en Francesc i la Fina. A la meva companya, Zhang Yajing. Per la seva ajuda i comprensió. AGRADECIMIENTOS Quisiera dar mis agradecimientos al Dr. Manel Ollé. Su apoyo en todo momento ha sido crucial para llevar a cabo esta tesis doctoral. Del mismo modo, a mis padres, Francesc y Fina y a mi esposa, Zhang Yajing, por su comprensión y logística. Ellos han hecho que los días tuvieran más de veinticuatro horas. Igualmente, a mi hermano Roger, que ha solventado más de una duda técnica en clave informática. Y como no, a mi hijo, Eric, que ha sido un gran obstáculo a la hora de redactar este trabajo, pero también la mayor motivación. Un especial reconocimiento a Zheng Liuyi, mi contacto en Beijing. Fue mi ángel de la guarda cuando viví en aquella ciudad y siempre que charlamos me ofrece una versión interesante sobre la actualidad académica china. Por otro lado, agradecer al grupo de los “Aspasians” aquellos descansos entra página y página, aquellos menús que hicieron más llevadero el trabajo solitario de investigación y redacción: Xavier Ortells, Roberto Figliulo, Manuel Pavón, Rafa Caro y Sergio Sánchez. v RESUMEN En esta tesis se analizará la obra de Yuan Muzhi, especialmente los filmes que dirigió, su debut, Scenes of City Life (都市風光,1935) y su segunda y última obra Street Angel ( 马路天使, 1937). Para ello se propone el concepto comedia modernista de Shanghai, como una perspectiva alternativa a las que se han mantenido tanto en la academia china como en la anglosajona. -

Pop Songs Between 1930S and 1940S in Shanghai”—Aesthetic Release of Eros Utopia

Journal of Literature and Art Studies, December 2016, Vol. 6, No. 12, 1545-1548 doi: 10.17265/2159-5836/2016.12.010 D DAVID PUBLISHING Behind “Pop Songs Between 1930s and 1940s in Shanghai”—Aesthetic Release of Eros Utopia ZHOU Xiaoyan Yancheng Institute of Technology, Jiangsu, China CANG Kaiyan, ZHOU Hanlu Jiangsu Yancheng Middle School, Jiangsu, China “Pop Songs between 1930s and 1940s in Shanghai” contains the artistic phenomenon with the utopian feature. Its main objective lies in the will instead of hope. The era endows different aesthetic utopian meanings to “Pop Songs between 1930s and 1940s in Shanghai”. After 2010, the utopian change of such songs is closely related to the contradiction between “aesthetic imagination and reality”, and “individual interest and integrated social interest” that are intrinsic in the utopian concept. To sort out the utopian process of those songs, it is helpful for correcting the current status about the weakened critical realism function of the current art, and accelerating the arousal of the literary and artistic creation, and individual consciousness, laying equal stress on and gathering the aesthetic power of these individuals, which provides solid foundation for the generalization of aesthetic utopian significance. Keywords: Shanghai Oldies (Pop Songs between 1930s and 1940s in Shanghai), aesthetic utopia, internal contradiction Introduction “Shanghai Oldies” refers to the pop songs that were produced and popular in Shanghai, sung widely over the country from 1930s to 1940s. It presents the graceful charm related to the south of the Yangtze River between grace and joy feature. It not only shows the memory of metropolis (invested with foreign adventures) in Old Shanghai, but also creates “Eros Utopia” based on presenting the ordinary love, instead of perfect political institution planning. -

Mulan (1998), Mulan Joins the Army (1939), and a Millennium-Long Intertextual Metamorphosis

arts Article Cultural “Authenticity” as a Conflict-Ridden Hypotext: Mulan (1998), Mulan Joins the Army (1939), and a Millennium-Long Intertextual Metamorphosis Zhuoyi Wang Department of East Asian Languages and Literatures, Hamilton College, Clinton, NY 13323, USA; [email protected] Received: 6 June 2020; Accepted: 7 July 2020; Published: 10 July 2020 Abstract: Disney’s Mulan (1998) has generated much scholarly interest in comparing the film with its hypotext: the Chinese legend of Mulan. While this comparison has produced meaningful criticism of the Orientalism inherent in Disney’s cultural appropriation, it often ironically perpetuates the Orientalist paradigm by reducing the legend into a unified, static entity of the “authentic” Chinese “original”. This paper argues that the Chinese hypotext is an accumulation of dramatically conflicting representations of Mulan with no clear point of origin. It analyzes the Republican-era film adaptation Mulan Joins the Army (1939) as a cultural palimpsest revealing attributes associated with different stages of the legendary figure’s millennium-long intertextual metamorphosis, including a possibly nomadic woman warrior outside China proper, a Confucian role model of loyalty and filial piety, a Sinitic deity in the Sino-Barbarian dichotomy, a focus of male sexual fantasy, a Neo-Confucian exemplar of chastity, and modern models for women established for antagonistic political agendas. Similar to the previous layers of adaptation constituting the hypotext, Disney’s Mulan is simply another hypertext continuing Mulan’s metamorphosis, and it by no means contains the most dramatic intertextual change. Productive criticism of Orientalist cultural appropriations, therefore, should move beyond the dichotomy of the static East versus the change-making West, taking full account of the immense hybridity and fluidity pulsing beneath the fallacy of a monolithic cultural “authenticity”. -

Art, Politics, and Commerce in Chinese Cinema

Art, Politics, and Commerce in Chinese Cinema edited by Ying Zhu and Stanley Rosen Hong Kong University Press 14/F Hing Wai Centre, 7 Tin Wan Praya Road, Aberdeen, Hong Kong www.hkupress.org © Hong Kong University Press 2010 Hardcover ISBN 978-962-209-175-7 Paperback ISBN 978-962-209-176-4 All rights reserved. Copyright of extracts and photographs belongs to the original sources. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the copyright owners. Printed and bound by XXXXX, Hong Kong, China Contents List of Tables vii Acknowledgements ix List of Contributors xiii Introduction 1 Ying Zhu and Stanley Rosen Part 1 Film Industry: Local and Global Markets 15 1. The Evolution of Chinese Film as an Industry 17 Ying Zhu and Seio Nakajima 2. Chinese Cinema’s International Market 35 Stanley Rosen 3. American Films in China Prior to 1950 55 Zhiwei Xiao 4. Piracy and the DVD/VCD Market: Contradictions and Paradoxes 71 Shujen Wang Part 2 Film Politics: Genre and Reception 85 5. The Triumph of Cinema: Chinese Film Culture 87 from the 1960s to the 1980s Paul Clark vi Contents 6. The Martial Arts Film in Chinese Cinema: Historicism and the National 99 Stephen Teo 7. Chinese Animation Film: From Experimentation to Digitalization 111 John A. Lent and Ying Xu 8. Of Institutional Supervision and Individual Subjectivity: 127 The History and Current State of Chinese Documentary Yingjin Zhang Part 3 Film Art: Style and Authorship 143 9. -

Xia, Liyang Associate Professor at Centre for Ibsen Studies, University

Xia, Liyang Associate Professor at Centre for Ibsen Studies, University of Oslo Address: Henrik Wergelandshus, Niels Henrik Abels vei 36, 0313 OSLO, Norway Postal address: Postboks 1168, Blindern, 0318 Oslo, Norway Title: A Myth that Glorifies: Rethinking Ibsen’s early reception in China Author responsible for correspondence and correction of proofs: Xia, Liyang 1 A Myth that Glorifies: Rethinking Ibsen’s Early Reception in China Introduction There is a consensus among Ibsen scholars and scholars of Chinese spoken drama that the Spring Willow Society staged A Doll’s House in Shanghai in 1914 (e.g. A Ying / Qian 1956; Ge 1982; Eide 1983; Tam 1984, 2001; He 2004, 2009; Chang 2004; Tian and Hu 2008; Tian and Song 2013). In 2014, when the National Theatre in Beijing staged A Doll’s House to commemorate the centenary of this premiere,1 most of the news reports and theatre advertisements cited the Spring Willow Society’s prior performance.2 Scholars and journalists who write about the history of A Doll’s House in China agree in general not only that the performance took place but that it was the first performance of an Ibsen play in China.3 I myself referred to this performance in my doctoral thesis (Xia 2013). In recent years, however, doubts have emerged not only about the claim that the Spring Willow Society performed A Doll’s House, but that the Society performed any plays by Ibsen. The following scholars have asserted that there is no concrete evidence that the performance of A Doll’s House took place: Seto Hiroshi (2002, 2015), Huang Aihua -

8Th Textile Bioengineering and Informatics Symposium Proceedings (TBIS 2015)

8th Textile Bioengineering and Informatics Symposium Proceedings (TBIS 2015) Zadar, Croatia 14 - 17 June 2015 Editors: Yi Li Budimir Mijovic Jia-Shen Li ISBN: 978-1-5108-1325-0 Printed from e-media with permission by: Curran Associates, Inc. 57 Morehouse Lane Red Hook, NY 12571 Some format issues inherent in the e-media version may also appear in this print version. Copyright© (2015) by Textile Bioengineering and Informatics Society (TBIS) All rights reserved. Printed by Curran Associates, Inc. (2016) For permission requests, please contact Textile Bioengineering and Informatics Society (TBIS) at the address below. Textile Bioengineering and Informatics Society (TBIS) Hong Kong Polytechnic University ST733 Hung Hom, Hong Kong Phone: (852) 9771 6139, 2766 6479 Fax: (852) 2764 5489 [email protected] Additional copies of this publication are available from: Curran Associates, Inc. 57 Morehouse Lane Red Hook, NY 12571 USA Phone: 845-758-0400 Fax: 845-758-2633 Email: [email protected] Web: www.proceedings.com PROCEEDINGS OF TBIS 2015 TABLE OF CONTENT Track 1 Textile Material Bioengineering 1 Preparation and Mechanical Characterization of Luffa Fibre Reinforced Low Density Polyethylene Composites Levent Onal, Yekta Karaduman, Cagrialp Arslan 1 2 Optimum Pyrolysis of Waste Acrylic Fibers for Preparation of Activated Carbon Vijay Baheti, Salman Naeem, Jiri Militky, Rajesh Mishra, Blanka Tomkova 7 3 Study on Comfort of Knitted Fabric Blended with PTT Fibers Xiu-E Bai, Xiao-Yu Han, Dong-Yan Wu, Ling Chen, Wei Wang 1 5 4 New Approach to Yarn -

From Textual to Historical Networks: Social Relations in the Bio-Graphical Dictionary of Republican China Cécile Armand, Christian Henriot

From Textual to Historical Networks: Social Relations in the Bio-graphical Dictionary of Republican China Cécile Armand, Christian Henriot To cite this version: Cécile Armand, Christian Henriot. From Textual to Historical Networks: Social Relations in the Bio-graphical Dictionary of Republican China. Journal of Historical Network Research, In press. halshs-03213995 HAL Id: halshs-03213995 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-03213995 Submitted on 8 Jun 2021 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. ARMAND, CÉCILE HENRIOT, CHRISTIAN From Textual to Historical Net- works: Social Relations in the Bio- graphical Dictionary of Republi- can China Journal of Historical Network Research x (202x) xx-xx Keywords Biography, China, Cooccurrence; elites, NLP From Textual to Historical Networks 2 Abstract In this paper, we combine natural language processing (NLP) techniques and network analysis to do a systematic mapping of the individuals mentioned in the Biographical Dictionary of Republican China, in order to make its underlying structure explicit. We depart from previous studies in the distinction we make between the subject of a biography (bionode) and the individuals mentioned in a biography (object-node). We examine whether the bionodes form sociocentric networks based on shared attributes (provincial origin, education, etc.). -

Movie Justice: the Legal System in Pre-1949 Chinese Film

Movie Justice: The Legal System in Pre-1949 Chinese Film Alison W. Conner* INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................ 1 I. CRIMINAL JUSTICE IN THE MOVIES ........................................................ 6 A. In the Hands of the Police: Arrest and Detention ........................ 7 B. Courtroom Scenes: The Defendant on Trial .............................. 16 C. Behind Bars: Prisons and Executions ........................................ 20 II. LAWYERS GOOD AND BAD ................................................................. 26 A. A Mercenary Lawyer in Street Angel ......................................... 26 B. The Lawyer as Activist: Bright Day ........................................... 28 III. DIVORCE IN THE MOVIES .................................................................... 31 A. Consultations with a Lawyer ...................................................... 31 B. Long Live the Missus: The Lawyer as Friend ............................ 34 IV. CONCLUSION ...................................................................................... 37 INTRODUCTION China’s fifth generation of filmmakers has brought contemporary Chinese films to international attention, and their social themes often illustrate broad legal concerns.1 In Zhang Yimou’s 1992 film, The Story of Qiu Ju, for example, Qiu Ju consults lawyers and brings a lawsuit, and more recent movies highlight legal issues too.2 Such film portrayals are of * Professor of Law, William S. Richardson -

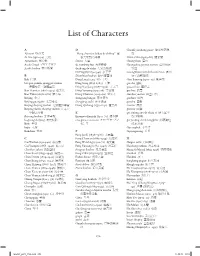

List of Characters

List of Characters A D Guanli yaoshang guize 䭉䎮喍⓮夷 Ajinomi 味の美 “Dang chuntian laidao de shihou” 䔞 ⇯ Ai Xia (1912–34) 刦曆 㗍⣑Ἦ⇘䘬㗪῁ Guan Zilan (1903–86) 斄䳓嗕 Ajinomoto 味の素 Daxue ⣏⬠ Guangzhou ⺋ⶆ Asahi Graph アサヒグラフ da yundong hui ⣏忳≽㚫 Guangzhou guomin xinwen ⺋ⶆ⚳㮹 Asahi shinbun 朝日新聞 dazhong de yishu ⣏䛦䘬喅埻 㕘倆 Di Pingzi (1879–1941) 䉬⸛⫸ Guangzhou nuzi shifan xuexiao ⺋ⶆ B Dianshizai huabao 溆䞛滳䔓⟙ ⤛⫸ⷓ䭬⬠㟉 Bali 湶 Ding Ling (1904–86) ᶩ䍚 Guo Jianying (1907–79) 悕⺢劙 baoguo yumin, qiangguo fumin Ding Song (1891-1969) ᶩあ guochi ⚳」 ᾅ⚳做㮹炻⻟⚳㮹 Ding Wenjiang (1887–1936) ᶩ㔯㰇 guocui hua ⚳䱡䔓 Bao Tianxiao (1876–1973) ⊭⣑䪹 Ding Yanyong (1902-78) ᶩ埵 guohua ⚳䔓 Bao Yahui (1898-1982) 欹Ṇ㘱 Dong Chuncai (1905–90) 吋䲼ㇵ Guohua yuekan ⚳䔓㚰↲ Beijing ⊿Ṕ dongfang bingfu 㜙㕡䕭⣓ guohuo ⚳屐 Beijing guangshe ⊿Ṕ䣦 Dongfang zazhi 㜙㕡暄娴 guoshu ⚳埻 Beijing sheying xuehui ⊿Ṕ㓅⼙⬠㚫 Dong Qichang (1555–1636) 吋℞㖴 Guotai ⚳㲘 Beiping daxue sheying xuehui ⊿⸛⣏ guoxue ⚳⬠ ⬠㓅⼙⬠㚫 E gei xinling zuo de shafa yi 䴎⽫曰⛸ Beiyang huabao ⊿㲳䔓⟙ Enomoto Kenichi (1904-70) 榎本健一 䘬㱁䘤㢭 boguang shuying 㲊㧡⼙ ero, guro, nansensu エロ・グロ・ナン gei yanjing chi de bingqilin 䴎䛤䜃⎫ Buin ิၨ センス 䘬⅘㵯㵳 bujie ᶵ㻼 Gyeongbok ઠฟ Bukchon ีᆀ F Gyeongseong ઠໜ Fang Junbi (1898–1986) 㕡⏃䑏 C Feng Chaoran (1882–1954) 楖崭䃞 H Cai Weilian (1904-40) 哉⦩ Feng Wenfeng (1900-71) 楖㔯沛 Haiguo tuzhi 㴟⚳⚾⽿ Cai Yuanpei (1868–1940) 哉⃫➡ Feng Yuxiang (1882–1948) 楖䌱䤍 Haishang fanhua 㴟ᶲ䷩厗 Chenbao fukan 㘐⟙∗↲ Fengyue huabao 桐㚰䔓⟙ Hamada Masuji (1892-1938) 浜田増治 Chen Baoyi (1893–1945) 昛㉙ᶨ Feng Zikai (1898–1975) 寸⫸ミ Hanbok ዽฟ Chen Duxiu (1879–1942) 昛䌐䥨 Fudan daxue ⽑㖎⣏⬠ Hankou 㻊⎋ -

UC Berkeley Cross-Currents: East Asian History and Culture Review

UC Berkeley Cross-Currents: East Asian History and Culture Review Title "Music for a National Defense": Making Martial Music during the Anti-Japanese War Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/7209v5n2 Journal Cross-Currents: East Asian History and Culture Review, 1(13) ISSN 2158-9674 Author Howard, Joshua H. Publication Date 2014-12-01 eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California “Music for a National Defense”: Making Martial Music during the Anti-Japanese War Joshua H. Howard, University of Mississippi Abstract This article examines the popularization of “mass songs” among Chinese Communist troops during the Anti-Japanese War by highlighting the urban origins of the National Salvation Song Movement and the key role it played in bringing songs to the war front. The diffusion of a new genre of march songs pioneered by Nie Er was facilitated by compositional devices that reinforced the ideological message of the lyrics, and by the National Salvation Song Movement. By the mid-1930s, this grassroots movement, led by Liu Liangmo, converged with the tail end of the proletarian arts movement that sought to popularize mass art and create a “music for national defense.” Once the war broke out, both Nationalists and Communists provided organizational support for the song movement by sponsoring war zone service corps and mobile theatrical troupes that served as conduits for musicians to propagate their art in the hinterland. By the late 1930s, as the United Front unraveled, a majority of musicians involved in the National Salvation Song Movement moved to the Communist base areas. Their work for the New Fourth Route and Eighth Route Armies, along with Communist propaganda organizations, enabled their songs to spread throughout the ranks. -

Lime Rock Gazette : October 31, 1850

A S A M 1 O «F WO i■W' f H (WT A TL I f t l R A T O B B VOLUME V. ROCKLAND, MAINE, THURSDAY MORNING, OCTOBER 31. 1850. NUMBER XL. T H E D E M O N B R I D E . about 20 men lying immovable on the flat of tied to splash and plunge, nnd blow, nnd make CHOOSING A HUSBAND. l.u t us now lorn to Isabel. Bail as rep.ort T H E M U S E . ------ 1 their stomachs in solemn silence anil with her circular course, varying me along with her made her husband it did not tell half tlio i l ’ oetry is the silver setting of golden thought, “ >nta Bena, the \c iv Orleans correspondent of their heads buried in blankets. Presently they ns if I wits a fly nil her tail. Finding Iter tail The following story undertakes to it,form the j truth. Stanley now spent tlirp.e-fuurtbs of the Concordia( oneortlin IntclIntcll.cen 1 igeaeer,eer. hiin hisIds lastlast, lcttciletter. rniged ,|len)gl.|vcg ,,,, on n,| rnlirg gave me Imt a poor hold, as the only means o f girls nbout soniellting we presume they under-| |,is :j,ne in the city, anil during the other copies the report which appeared in the Ti ne securing my prey, I took out my knife, and stand in all its pros and nnu,—its d ifliru liit fourth, when he was at home, was morose to Delta, of the case of n man who Was nttcinptcd mninetl with their bodies halanecd in mill nir ntul emharassinents, full ns well ns our good Death of the Flowers. -

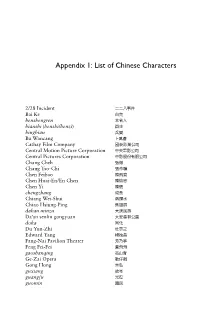

Appendix 1: List of Chinese Characters

Appendix 1: List of Chinese Characters 2/28 Incident 二二八事件 Bai Ke 白克 benshengren 本省人 bianshi (benshi/benzi) 辯士 bingbian 兵變 Bu Wancang 卜萬蒼 Cathay Film Company 國泰影業公司 Central Motion Picture Corporation 中央電影公司 Central Pictures Corporation 中影股份有限公司 Chang Cheh 張徹 Chang Tso-Chi 張作驥 Chen Feibao 陳飛寶 Chen Huai-En/En Chen 陳懷恩 Chen Yi 陳儀 chengzhang 成長 Chiang Wei- Shui 蔣謂水 Chiao Hsiung- Ping 焦雄屏 dahan minzu 大漢民族 Da’an senlin gongyuan 大安森林公園 doka 同化 Du Yun- Zhi 杜雲之 Edward Yang 楊德昌 Fang- Nai Pavilion Theater 芳乃亭 Feng Fei- Fei 鳳飛飛 gaoshanqing 高山青 Ge- Zai Opera 歌仔戲 Gong Hong 龔弘 guxiang 故鄉 guangfu 光復 guomin 國民 188 Appendix 1 guopian 國片 He Fei- Guang 何非光 Hou Hsiao- Hsien 侯孝賢 Hu Die 胡蝶 Huang Shi- De 黃時得 Ichikawa Sai 市川彩 jiankang xieshi zhuyi 健康寫實主義 Jinmen 金門 jinru shandi qingyong guoyu 進入山地請用國語 juancun 眷村 keban yingxiang 刻板印象 Kenny Bee 鍾鎮濤 Ke Yi-Zheng 柯一正 kominka 皇民化 Koxinga 國姓爺 Lee Chia 李嘉 Lee Daw- Ming 李道明 Lee Hsing 李行 Li You-Xin 李幼新 Li Xianlan 李香蘭 Liang Zhe- Fu 梁哲夫 Liao Huang 廖煌 Lin Hsien- Tang 林獻堂 Liu Ming- Chuan 劉銘傳 Liu Na’ou 劉吶鷗 Liu Sen- Yao 劉森堯 Liu Xi- Yang 劉喜陽 Lu Su- Shang 呂訴上 Ma- zu 馬祖 Mao Xin- Shao/Mao Wang- Ye 毛信孝/毛王爺 Matuura Shozo 松浦章三 Mei- Tai Troupe 美臺團 Misawa Mamie 三澤真美惠 Niu Chen- Ze 鈕承澤 nuhua 奴化 nuli 奴隸 Oshima Inoshi 大島豬市 piaoyou qunzu 漂游族群 Qiong Yao 瓊瑤 qiuzhi yu 求知慾 quanguo gejie 全國各界 Appendix 1 189 renmin jiyi 人民記憶 Ruan Lingyu 阮玲玉 sanhai 三害 shandi 山地 Shao 邵族 Shigehiko Hasumi 蓮實重彦 Shihmen Reservoir 石門水庫 shumin 庶民 Sino- Japanese Amity 日華親善 Society for Chinese Cinema Studies 中國電影史料研究會 Sun Moon Lake 日月潭 Taiwan Agricultural Education Studios