APPLE COMPUTER, INC. by Richard D

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Washington Apple Pi Journal, May 1986

$ 250 Wa/hington Apple Pi The Journal of Washingtond Apple Pi, Ltd. Volume. 8 ma,u 1986 number 5 HiQhliQhtl v - - -FAMILY HOME MONEY MANAGER: Part 1 -FORTH MERGESORT -ELIZA SPEAKS UP IN'CLASS -MACSPIES: KEEPING LITTLE SISTER OUT OFYOUR DIARY -MAC DISK SPEED COMPARISONS i In This Issu<Z... Officers & Staff, Editorial 3 Family Home Money Manager: Pt 1 .Brian G. Mason 32 President's Corner Tom Warrick 4 Eject UniDisk 3.5 ••• Stephe n Bach 36 Event Queue, General Information, Classifieds 5 GPLE & Double-Take: Dynamic Duo ••• Donald S. Kline 37 WAP Calendar, SigNews • ••• • 6 FORTH Mergesort • • • • Chester H. Page 38 Apple Teas •• • Amy T. Bill ings ley 7 Disk Drive Repair/Maint. Tutorial. • Ted Meyer 43 Minutes, Miscellaneous 7 Best of Apple Items - UBBS. Eu!:lid Coukouma 44 WAP Hbtline •••••• 8 Mac Q & A . • • Jonathan E. Hardis 48 Meetin9 Report: March 22 Adrien Youell 9 MacNovice • •• Ralph J. Begleiter 52 BBS Phone Numbers 9 Eliza Speaks Up in Class ••• Bill Hershey 54 SwyftCard Replies •• • •••Jef Raskin 10 MacSpies: •• • John B. Yellot Jr. 56 EdSIG News • • • •• Peter Combes 12 Frederick Apple Core • • •• • • 62 Grademaster: A Review • Randy C. Zittel 14 Macintosh Communication ••Lynn R. Trusal 62 Apple III News •• David Ottalini 16 WAP Acrost ic • • •• Professor Apple 63 UniDisk 3.5 for Apple III • Tom Bartkiewicz 18 An Overview of Data Base Management •• Bill Hole 64 Letter to the Editor David Ottalini 19 Work-n-Print Martin O. Milrod 66 Q & A • Bruce F. Field 20 Requiescat In Pace? • ~artin Kuhn 67 FEDSIG Report • • Chuck Weger 24 'EXCEL'ing With Your r~ac •• David Morganstein 68 New AppleWorks SIG Peg Matzen 24 Macintosh Disk Speed Comparisons. -

Microsoft Word 1 Microsoft Word

Microsoft Word 1 Microsoft Word Microsoft Office Word 2007 in Windows Vista Developer(s) Microsoft Stable release 12.0.6425.1000 (2007 SP2) / April 28, 2009 Operating system Microsoft Windows Type Word processor License Proprietary EULA [1] Website Microsoft Word Windows Microsoft Word 2008 in Mac OS X 10.5. Developer(s) Microsoft Stable release 12.2.1 Build 090605 (2008) / August 6, 2009 Operating system Mac OS X Type Word processor License Proprietary EULA [2] Website Microsoft Word Mac Microsoft Word is Microsoft's word processing software. It was first released in 1983 under the name Multi-Tool Word for Xenix systems.[3] [4] [5] Versions were later written for several other platforms including IBM PCs running DOS (1983), the Apple Macintosh (1984), SCO UNIX, OS/2 and Microsoft Windows (1989). It is a component of the Microsoft Office system; however, it is also sold as a standalone product and included in Microsoft Microsoft Word 2 Works Suite. Beginning with the 2003 version, the branding was revised to emphasize Word's identity as a component within the Office suite; Microsoft began calling it Microsoft Office Word instead of merely Microsoft Word. The latest releases are Word 2007 for Windows and Word 2008 for Mac OS X, while Word 2007 can also be run emulated on Linux[6] . There are commercially available add-ins that expand the functionality of Microsoft Word. History Word 1981 to 1989 Concepts and ideas of Word were brought from Bravo, the original GUI writing word processor developed at Xerox PARC.[7] [8] On February 1, 1983, development on what was originally named Multi-Tool Word began. -

Intro to Ios

Please download Xcode! hackbca.com/ios While installing, ensure you have administrator access. Download our sound and image files at hackbca.com/ios - you’ll be using them in this workshop. iOS Development with SwiftUI Anthony Li Room 138 Link Welcome [HOME ADDRESS CENSORED] Anthony Li - https://anli.dev ATCS ‘22 Just download it “The guy who made YourBCABus” 1 History 2 Introduction to Swift 3 Duck Clicker 4 hackBCA Schedule Viewer History • 13.8 billion years ago, there was a Big Bang. 1984 OG GUI The Macintosh 1984 Do you want to sell sugar water for the rest of your life, or do you want to come with me and change the world? Steve Jobs John Sculley 19841985 sure i guess btw ur fired now Steve Jobs John Sculley 1985 • Unix-based GUI! • Object-oriented programming! • Drag-and-drop app building! Steve Jobs • First computer to host a web server! ONLY $6,500! NeXTSTEP OS AppKit Foundation UNIX 1997 btw ur hired now. first give me a small loan of $429 million Steve Jobs 1997 Apple buys NeXT. Mac OS X AppKit Foundation UNIX 2007 iPhone OS AppKit “UIKit” Foundation UNIX 2014 Swift Objective-C 2019 SwiftUI UIKit iOS Your Apps UIKit SwiftUI Foundation Quartz Objective-C Swift UNIX 1 History 2 Introduction to Swift 3 Duck Clicker 4 hackBCA Schedule Viewer 1 History 2 Introduction to Swift 3 Duck Clicker 4 hackBCA Schedule Viewer Text Button Image List struct MyView: Button View View View Button 1 History 2 Introduction to Swift 3 Duck Clicker 4 hackBCA Schedule Viewer Master Detail Master Detail Master Detail iOS Your Apps UIKit SwiftUI Foundation Quartz Objective-C Swift UNIX SwiftUI UIKit MapKit: MKMapView UIKit-based. -

Beckman, Harris

CHARM 2007 Full Papers CHARM 2007 The Apple of Jobs’ Eye: An Historical Look at the Link between Customer Orientation and Corporate Identity Terry Beckman, Queen’s University, Kingston ON, CANADA Garth Harris, Queen’s University, Kingston ON, CANADA When a firm has a strong customer orientation, it Marketing literature positively links a customer orientation essentially works at building strong relationships with its with corporate performance. However, it does not customers. While this is a route to success and profits for a elaborate on the mechanisms that allow a customer firm (Reinartz and Kumar 2000), it is only successful if a orientation to function effectively. Through a customer customer sees value in the relationship. It has been shown orientation a firm builds a relationship with the customer, that customers reciprocate, and build relationships with who in turn reciprocates through an identification process. companies and brands (Fournier 1998). However, in This means that the identity of a firm plays a significant forming a relationship with the firm, customers do this role in its customer orientation. This paper proposes that through an identification process; that is, they identify with customer orientation is directly influenced by corporate the firm or brand (e.g., Battacharya and Sen 2003; identity. When a firm’s identity influences its customer McAlexander and Schouten, Koening 2002, Algesheimer, orientation, firm performance will be positively impacted. Dholakia and Herrmann 2005), and see value in that An historical analysis shows three phases of Apple, Inc.’s corporate identity and relationship. While a customer life during which its identity influences customer orientation establishes a focus on customers, there are many orientation; then where Apple loses sight of its original different ways and directions that a customer focus can go. -

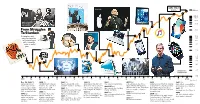

From Struggles to Stardom

AAPL 175.01 Steve Jobs 12/21/17 $200.0 100.0 80.0 17 60.0 Apple co-founders 14 Steve Wozniak 40.0 and Steve Jobs 16 From Struggles 10 20.0 9 To Stardom Jobs returns Following its volatile 11 10.0 8.0 early years, Apple has 12 enjoyed a prolonged 6.0 period of earnings 15 and stock market 5 4.0 gains. 2 7 2.0 1.0 1 0.8 4 13 1 6 0.6 8 0.4 0.2 3 Chart shown in logarithmic scale Tim Cook 0.1 1980 ’82 ’84 ’86’88 ’90 ’92 ’94 ’96 ’98 ’00 ’02 ’04 ’06’08 ’10 ’12 ’14 ’16 2018 Source: FactSet Dec. 12, 1980 (1) 1984 (3) 1993 (5) 1998 (8) 2003 2007 (12) 2011 2015 (16) Apple, best known The Macintosh computer Newton, a personal digital Apple debuts the iMac, an The iTunes store launches. Jobs announces the iPhone. Apple becomes the most valuable Apple Music, a subscription for the Apple II home launches, two days after assistant, launches, and flops. all-in-one desktop computer 2004-’05 (10) Apple releases the Apple TV publicly traded company, passing streaming service, launches. and iPod Touch, and changes its computer, goes public. Apple’s iconic 1984 1995 (6) with a colorful, translucent Apple unveils the iPod Mini, Exxon Mobil. Apple introduces 2017 (17 ) name from Apple Computer. Shares rise more than Super Bowl commercial. Microsoft introduces Windows body designed by Jony Ive. Shuffle, and Nano. the iPhone 4S with Siri. Tim Cook Introduction of the iPhone X. -

Effectively Communicating Y Ating Your Department's Worth

stayinging relrelevant Effectively communicatatinging yyour department’s worth Getting thee Cart before the Horse Stayinging ReRelevant Everythingng I lealearned about marketinarketing I learned from an Apple & the Circus Let’s talklk aboabout Apple Let’s Talkalk aboabout Apple 1976 - Steve Wozniak designs new computeruter (A(Apple I) & 21 year old Steve Jobs convinces him to take it commercial 1977 - Apple II becomes instant success 1980 - Apple sales soar to $1 million-a-yearear & ccompany goes public 1983 - John Sculley recruited to help buildld compcompany 1984 - Big Brother Superbowl ad 1985 - Jobs ousted by Sculley and board 1991 - Alliances with IBM and Motorola 1993 - Sculley ousted after handheld Newtonwton prproject fails 1984 SuperbSuperbowl Ad QuickTime™Time™ and a decompresompressor are needed to see ththis picture. Let’s Talkalk aboabout Apple 1976 - Steve Wozniak designs new computer (Apple 1) & 21 year old Steve Jobs convinces him to tak it commercial 1977 - Apple II becomes instant success 1980 - Apple sales soar to $1 million-a-year & compacompany goes public 1983 - John Sculley recruited to help build companypany 1984 - Big Brother Superbowl ad 1985 - Jobs ousted by Sculley and board 1991 - Alliances with IBM and Motorola 1993 - Sculley ousted after handheld Newton project fails 1996 - Apple acquires NeXT Software And then 1997 hhappened... QuickTime™Time™ and a decompreompressor are needed to see ththis picture. Communicatingicating the value Thinknk DiffeDifferent Marketing is about valulueses. This is a very complicated world. It's's a ververy noisy world. We' re not going to get a chanancece fofor people to remember a lot about us. No compapanyny isis. -

Source Code for Apple's 1983 Lisa Computer to Be Made Public Next Year 31 December 2017, by Seung Lee, the Mercury News

Source code for Apple's 1983 Lisa computer to be made public next year 31 December 2017, by Seung Lee, The Mercury News The museum's software curator, Al Kossow, announced to a public mailing list that the source code for the Lisa computer has been recovered and is with Apple for review. Once Apple clears the code, the museum plans to release it to the public with a blog post explaining the code's historic significance. However, not every part of Lisa's source code will be available, Kossow said. "The only thing I saw that probably won't be able to be released is the American Heritage dictionary for the spell checker in LisaWrite (word processing application)," he said. The Lisa was the first computer with a graphical user interface aimed at businesses—hence its high cost. With a processor as fast as 5 MHz and 1 MB of RAM, the Lisa computer gave users the breakthrough technology of organizing files by Apple Lisa with a ProFile hard drive stacked on top of it. using a computer mouse. Credit: Stahlkocher/ GNU Free Documentation License Apple spent $150 million on the development of Lisa and advertised it as a game-changer, with actor Kevin Costner in the commercials. But Apple Before there was an iPhone, iMac or Macintosh, only sold 10,000 units of Lisa in 1983 and pivoted Apple had the Lisa computer. to create a smaller and much cheaper successor, the Macintosh, which was released the next year. The Lisa computer—which stands for Local Integrated Software Architecture but was also "The Lisa was doomed because it was basically a named after Steve Jobs' eldest daughter—was a prototype—an overpriced, underpowered cobbled- flop when it released in 1983 because of its together ramshackle Mac," author and tech astronomical price of $10,000 - $24,700 when journalist Leander Kahney told Wired in 2010. -

The History of the Ipad

Proceedings of the New York State Communication Association Volume 2015 Article 3 2016 The iH story of the iPad Michael Scully Roger Williams University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://docs.rwu.edu/nyscaproceedings Part of the Communication Technology and New Media Commons, Journalism Studies Commons, and the Mass Communication Commons Recommended Citation Scully, Michael (2016) "The iH story of the iPad," Proceedings of the New York State Communication Association: Vol. 2015 , Article 3. Available at: http://docs.rwu.edu/nyscaproceedings/vol2015/iss1/3 This Conference Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at DOCS@RWU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Proceedings of the New York State Communication Association by an authorized editor of DOCS@RWU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The iH story of the iPad Cover Page Footnote Thank you to Roger Williams University and Salve Regina University. This conference paper is available in Proceedings of the New York State Communication Association: http://docs.rwu.edu/ nyscaproceedings/vol2015/iss1/3 Scully: iPad History The History of the iPad Michael Scully Roger Williams University __________________________________________________________________ The purpose of this paper is to review the history of the iPad and its influence over contemporary computing. Although the iPad is relatively new, the tablet computer is having a long and lasting affect on how we communicate. With this essay, I attempt to review the technologies that emerged and converged to create the tablet computer. Of course, Apple and its iPad are at the center of this new computing movement. -

Gary L. Patsley Gary Patsley Had a Career in the Financial Services Industry for Over Three Decades

Gary L. Patsley Gary Patsley had a career in the financial services industry for over three decades. He retired as Chief Financial Officer of Bank of America-Texas and the Southwest. Mr. Patsley previously held similar positions at Bank One Texas and its predecessor companies. Prior to that he was a financial officer with a large national insurance group. After serving five years in the US Army, Mr. Patsley earned his BBA and MBA from the University of North Texas. He then worked at KPMG prior to his career in financial services. Gary has had leadership positions in several charitable organizations namely president of Dallas CASA, finance chair of the Dallas Arboretum and Botanical Garden and as an executive committee member of The Visiting Nurses Association of Texas. He was a founding member, donor and finance chairman of the Metro Dallas Homeless Alliance, a first of its kind public-private partnership to address the urgent needs of the homeless. Gary and his wife have also been active supporters of the Boys and Girls Club of America. He has been married to Pam Patsley for 33 years. They have 3 children and 4 grandchildren. In addition to their residence in Palm Beach, they also have a home in Dallas. Michael B. Picotte Following graduation from The Villanova School of Business and military service, Michael joined his family in the Real Estate business in Albany N.Y. He later completed the Presidents and Owners Management Program of Harvard Graduate School of Business. He has been a director of State Bank of Albany 1982-1989, Fleet Bank 1989-1999 and Fleet Boston Financial 1999-2004. -

A History of the Personal Computer Index/11

A History of the Personal Computer 6100 CPU. See Intersil Index 6501 and 6502 microprocessor. See MOS Legend: Chap.#/Page# of Chap. 6502 BASIC. See Microsoft/Prog. Languages -- Numerals -- 7000 copier. See Xerox/Misc. 3 E-Z Pieces software, 13/20 8000 microprocessors. See 3-Plus-1 software. See Intel/Microprocessors Commodore 8010 “Star” Information 3Com Corporation, 12/15, System. See Xerox/Comp. 12/27, 16/17, 17/18, 17/20 8080 and 8086 BASIC. See 3M company, 17/5, 17/22 Microsoft/Prog. Languages 3P+S board. See Processor 8514/A standard, 20/6 Technology 9700 laser printing system. 4K BASIC. See Microsoft/Prog. See Xerox/Misc. Languages 16032 and 32032 micro/p. See 4th Dimension. See ACI National Semiconductor 8/16 magazine, 18/5 65802 and 65816 micro/p. See 8/16-Central, 18/5 Western Design Center 8K BASIC. See Microsoft/Prog. 68000 series of micro/p. See Languages Motorola 20SC hard drive. See Apple 80000 series of micro/p. See Computer/Accessories Intel/Microprocessors 64 computer. See Commodore 88000 micro/p. See Motorola 80 Microcomputing magazine, 18/4 --A-- 80-103A modem. See Hayes A Programming lang. See APL 86-DOS. See Seattle Computer A+ magazine, 18/5 128EX/2 computer. See Video A.P.P.L.E. (Apple Pugetsound Technology Program Library Exchange) 386i personal computer. See user group, 18/4, 19/17 Sun Microsystems Call-A.P.P.L.E. magazine, 432 microprocessor. See 18/4 Intel/Microprocessors A2-Central newsletter, 18/5 603/4 Electronic Multiplier. Abacus magazine, 18/8 See IBM/Computer (mainframe) ABC (Atanasoff-Berry 660 computer. -

Headway Fourth Edition Upper-Intermediate Reading Text

Apple Mac or PC? For many, home computers have become synonymous with Windows and Bill Gates, but there has always been a loyal band of Apple users, whose devotion to the brand and its co-founder, the late Steve Jobs, is almost religious. Within minutes of his death on October 5, 2011, Twitter was overwhelmed with tributes from shocked fans. In the hours and days that followed, thousands of people made their way to Apple headquarters in California and to Apple Stores right across the world to lay flowers and light candles. In a fitting tribute to this gadget guru, many held up an image of a burning candle on their iPhone or iPad. So how did a company named after a fruit create so many fans? Headway Fourth edition Upper-Intermediate Student’s Book Unit 6 pp.50–51 © Oxford University Press 20 14 1 Steve Jobs and Steven Wozniak dropped out of college and got jobs in Silicon Valley, where they founded the Apple Computer company in 1976, the name based on Jobs’ favourite fruit. They designed the Apple I computer in Jobs’ bedroom, having raised the capital by selling their most valued possessions – an old Volkswagen bus and a scientific calculator. The later model, the Apple Macintosh, introduced the public to point and click graphics. It was the first home computer to be truly user-friendly, or as the first advertising “Other campaign put it, ‘the computer for the rest of us’. companies When IBM released its first PC in1 981, Jobs realized that don’t care Apple would have to become a more grown-up company in about design. -

To Grow Your Business

GAME CHANGERS To Grow Your StayBusiness, Forever If you know where and how to look, innovation opportunities are everywhere, says former Apple and Pepsi CEO John Sculley. BY PAUL GILLIN PORTRAITS BY JOSH RITCHIE 60 INSIGNIAM QUARTERLY | Spring 2016 INSIGNIAM QUARTERLY COPYRIGHT © INSIGNIAM HOLDING LLC. SPRING 2016 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. REPRINTED WITH PERMISSION. Forever Curious quarterly.insigniam.com | INSIGNIAM QUARTERLY 61 INSIGNIAM QUARTERLY COPYRIGHT © INSIGNIAM HOLDING LLC. SPRING 2016 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. REPRINTED WITH PERMISSION. At an age when many executives are playing golf or writing memoirs, John Sculley is sounding he adds. Kodak, for example, could have owned the alarm. digital photography, but it was too focused on defending its legacy business. The former CEO of Apple and Pepsi-Cola Such commentary is almost de rigueur from says many of today’s corporate giants are an up-and-coming tech entrepreneur; it’s less about to be bulldozed into oblivion unless expected from a veteran of big, established or- they take action—now. ganizations. But Sculley has long understood Cloud computing, mobility and machine the power customers wield over a company’s intelligence will soon trigger an explosion of fate. More than 40 years ago, he watched a innovation, he says. Entrepreneurs can start grandmother sip cola samples from two un- companies with a fraction of the resources marked paper cups. To her surprise, the life- that were necessary just a few years ago, and long Coke drinker discovered she preferred they can move with unprecedented speed and the taste of Pepsi. That insight led to the Pepsi agility.