The History of the Ipad

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Student Technology Use 2012

Student Technology Use 2012 Welcome! This survey is being conducted by Librarians at the Newton Gresham Library at SHSU. We are interested in our students' use of current and emerging technology such as tablets and e-readers. This survey will take approximately 10-20 minutes and you may exit at any time if you change your mind about participating. No personally identifying information is required to participate. You do have the option to provide your SHSU email address at the end of the survey to enter a prize drawing; the winner will receive a free Barnes & Noble NOOK HD tablet! If you choose to enter the prize drawing, your email address will not be used for any other purpose and will be deleted after the drawing is complete. If you have questions or concerns regarding this survey, please contact the principal investigator, Erin Cassidy, at 936-294-4567 or [email protected]. Thank you for your participation! 1 Student Technology Use 2012 Other Technologies 1. Please mark all the technologies you recognize by name: Blogs Pinterest Chat / Instant Messaging (IM) Podcasts Delicious RSS E-reader SecondLife Facebook Skype / VOIP Foursquare / other geosocial networking sites Tablet Computer GoodReads Twitter Google+ YouTube MySpace None of them 2 Student Technology Use 2012 Internet & Computer Use 2. Do you have internet access at home? Dial-up I have internet, but don't know what kind DSL / Cable None, I don't have internet at home Satelite Other (please specify) 3. Do you have wifi / wireless internet at home? Yes Don't know No * 4. -

Steve Jobs' Diligence

Steve Jobs’ Diligence Full Lesson Plan COMPELLING QUESTION How can your diligence help you to be successful? VIRTUE Diligence DEFINITION Diligence is intrinsic energy for completing good work. LESSON OVERVIEW In this lesson, students will learn about Steve Jobs’ diligence in his life. They will also learn how to be diligent in their own lives. OBJECTIVES • Students will analyze Steve Jobs’ diligence throughout his life. • Students will apply their knowledge of diligence to their own lives. https://voicesofhistory.org BACKGROUND Steve Jobs was born in 1955. Jobs worked for video game company Atari, Inc. before starting Apple, Inc. with friend Steve Wozniak in 1976. Jobs and Wozniak worked together for many years to sell personal computers. Sales of the Macintosh desktop computer slumped, however, and Jobs was ousted from his position at Apple. Despite this failure, Jobs would continue to strive for success in the technology sector. His diligence helped him in developing many of the electronic devices that we use in our everyday life. VOCABULARY • Atari • Sojourn • Apple • Endeavor • NeXT • Contention • Pancreatic • Macintosh • Maternal • Pixar • Biological • Revolutionized • Tinkered INTRODUCE TEXT Have students read the background and narrative, keeping the Compelling Question in mind as they read. Then have them answer the remaining questions below. https://voicesofhistory.org WALK-IN-THE-SHOES QUESTIONS • As you read, imagine you are the protagonist. • What challenges are you facing? • What fears or concerns might you have? • What may prevent you from acting in the way you ought? OBSERVATION QUESTIONS • Who was Steve Jobs? • What was Steve Jobs’ purpose? • What diligent actions did Steve Jobs take in his life? • How did Steve Jobs help to promote freedom? DISCUSSION QUESTIONS Discuss the following questions with your students. -

Steve Wozniak Was Born in 1950 Steve Jobs in 1955, Both Attended Homestead High School, Los Altos, California

Steve Wozniak was born in 1950 Steve Jobs in 1955, both attended Homestead High School, Los Altos, California, Wozniak dropped out of Berkeley, took a job at Hewlett-Packard as an engineer. They met at HP in 1971. Jobs was 16 and Wozniak 21. 1975 Wozniak and Jobs in their garage working on early computer technologies Together, they built and sold a device called a “blue box.” It could hack AT&T’s long-distance network so that phone calls could be made for free. Jobs went to Oregon’s Reed College in 1972, quit in 1974, and took a job at Atari designing video games. 1974 Wozniak invited Jobs to join the ‘Homebrew Computer Club’ in Palo Alto, a group of electronics-enthusiasts who met at Stanford 1974 they began work on what would become the Apple I, essentially a circuit board, in Jobs’ bedroom. 1976 chiefly by Wozniak’s hand, they had a small, easy-to-use computer – smaller than a portable typewriter. In technical terms, this was the first single-board, microprocessor-based microcomputer (CPU, RAM, and basic textual-video chips) shown at the Homebrew Computer Club. An Apple I computer with a custom-built wood housing with keyboard. They took their new computer to the companies they were familiar with, Hewlett-Packard and Atari, but neither saw much demand for a “personal” computer. Jobs proposed that he and Wozniak start their own company to sell the devices. They agreed to go for it and set up shop in the Jobs’ family garage. Apple I A main circuit board with a tape-interface sold separately, could use a TV as the display system, text only. -

E-Book Readers Kindle Sony and Nook a Comparative Study

E-BOOK READERS KINDLE SONY AND NOOK: A COMPARATIVE STUDY Baban Kumbhar Librarian Rayat Shikshan Sanstha’s Dada Patil Mahavidyalaya, Karjat, Dist Ahmednagar E-mail:[email protected] Abstract An e-book reader is a portable electronic device for reading digital books and periodicals, better known as e- books. An e-book reader is similar in form to a tablet computer. Kindle is a series of e-book readers designed and marketed by Amazon.com. The Sony Reader was a line of e-book readers manufactured by Sony. NOOK is a brand of e-readers developed by American book retailer Barnes & Noble. Researcher compares three E-book readers in the paper. Keywords: e-book reader, Kindle, Sony, Nook 1. Introduction: An e-reader, also called an e-book reader or e-book device, is a mobile electronic device that is designed primarily for the purpose of reading digital e-books and periodicals. Any device that can display text on a screen may act as an e-book reader, but specialized e-book reader designs may optimize portability, readability (especially in sunlight), and battery life for this purpose. A single e-book reader is capable of holding the digital equivalent of hundreds of printed texts with no added bulk or measurable mass.[1] An e-book reader is similar in form to a tablet computer. A tablet computer typically has a faster screen capable of higher refresh rates which makes it more suitable for interaction. Tablet computers also are more versatile, allowing one to consume multiple types of content, as well as create it. -

Intro to Ios

Please download Xcode! hackbca.com/ios While installing, ensure you have administrator access. Download our sound and image files at hackbca.com/ios - you’ll be using them in this workshop. iOS Development with SwiftUI Anthony Li Room 138 Link Welcome [HOME ADDRESS CENSORED] Anthony Li - https://anli.dev ATCS ‘22 Just download it “The guy who made YourBCABus” 1 History 2 Introduction to Swift 3 Duck Clicker 4 hackBCA Schedule Viewer History • 13.8 billion years ago, there was a Big Bang. 1984 OG GUI The Macintosh 1984 Do you want to sell sugar water for the rest of your life, or do you want to come with me and change the world? Steve Jobs John Sculley 19841985 sure i guess btw ur fired now Steve Jobs John Sculley 1985 • Unix-based GUI! • Object-oriented programming! • Drag-and-drop app building! Steve Jobs • First computer to host a web server! ONLY $6,500! NeXTSTEP OS AppKit Foundation UNIX 1997 btw ur hired now. first give me a small loan of $429 million Steve Jobs 1997 Apple buys NeXT. Mac OS X AppKit Foundation UNIX 2007 iPhone OS AppKit “UIKit” Foundation UNIX 2014 Swift Objective-C 2019 SwiftUI UIKit iOS Your Apps UIKit SwiftUI Foundation Quartz Objective-C Swift UNIX 1 History 2 Introduction to Swift 3 Duck Clicker 4 hackBCA Schedule Viewer 1 History 2 Introduction to Swift 3 Duck Clicker 4 hackBCA Schedule Viewer Text Button Image List struct MyView: Button View View View Button 1 History 2 Introduction to Swift 3 Duck Clicker 4 hackBCA Schedule Viewer Master Detail Master Detail Master Detail iOS Your Apps UIKit SwiftUI Foundation Quartz Objective-C Swift UNIX SwiftUI UIKit MapKit: MKMapView UIKit-based. -

Young Children's Tablet Computer Play •

Young Children’s Tablet Computer Play • Thomas Enemark Lundtofte The author reviews the research and scholarly literature about young chil- dren’s play with tablet computers and identifies four major topics relevant to the subject—digital literacy, learning, transgressive and creative play, and parental involvement. He finds that young children’s tablet computer play relies not only on technology, but also on sociocultural conditions. He argues that research should pay greater attention to transgressive play and should in general treat play as an autotelic concept because the nuances of play are as important as its function. He calls attention to the lack of affordances for creativity in apps for young children, explores the need for parental involve- ment in young children’s tablet computer play, and discusses the importance of agency and access in such play. Key words: digital media; iPad; tablet computer; play and young children Introduction I aim to make clear what we know about young children’s play with tablet computers by considering research from the human sciences that mentions play, young children, and tablet computers (or similar terms). This leads me to a num- ber of questions, some of which have also been treated in the research—questions about the kind of play possible with a tablet computer and about what we even mean by “tablet computer play.” To provide a framework for these questions, I discuss play theory as well as theories on technological affordances and how this aspect of children’s play with technology corresponds with what we know about the nature of play in general. -

Tripadvisor Appoints Lindsay Nelson As President of the Company's Core Experience Business Unit

TripAdvisor Appoints Lindsay Nelson as President of the Company's Core Experience Business Unit October 25, 2018 A recognized leader in digital media, new CoreX president will oversee the TripAdvisor brand, lead content development and scale revenue generating consumer products and features that enhance the travel journey NEEDHAM, Mass., Oct. 25, 2018 /PRNewswire/ -- TripAdvisor, the world's largest travel site*, today announced that Lindsay Nelson will join the company as president of TripAdvisor's Core Experience (CoreX) business unit, effective October 30, 2018. In this role, Nelson will oversee the global TripAdvisor platform and brand, helping the nearly half a billion customers that visit TripAdvisor monthly have a better and more inspired travel planning experience. "I'm really excited to have Lindsay join TripAdvisor as the president of Core Experience and welcome her to the TripAdvisor management team," said Stephen Kaufer, CEO and president, TripAdvisor, Inc. "Lindsay is an accomplished executive with an incredible track record of scaling media businesses without sacrificing the integrity of the content important to users, and her skill set will be invaluable as we continue to maintain and grow TripAdvisor's position as a global leader in travel." "When we created the CoreX business unit earlier this year, we were searching for a leader to be the guardian of the traveler's journey across all our offerings – accommodations, air, restaurants and experiences. After a thorough search, we are confident that Lindsay is the right executive with the experience and know-how to enhance the TripAdvisor brand as we evolve to become a more social and personalized offering for our community," added Kaufer. -

Beckman, Harris

CHARM 2007 Full Papers CHARM 2007 The Apple of Jobs’ Eye: An Historical Look at the Link between Customer Orientation and Corporate Identity Terry Beckman, Queen’s University, Kingston ON, CANADA Garth Harris, Queen’s University, Kingston ON, CANADA When a firm has a strong customer orientation, it Marketing literature positively links a customer orientation essentially works at building strong relationships with its with corporate performance. However, it does not customers. While this is a route to success and profits for a elaborate on the mechanisms that allow a customer firm (Reinartz and Kumar 2000), it is only successful if a orientation to function effectively. Through a customer customer sees value in the relationship. It has been shown orientation a firm builds a relationship with the customer, that customers reciprocate, and build relationships with who in turn reciprocates through an identification process. companies and brands (Fournier 1998). However, in This means that the identity of a firm plays a significant forming a relationship with the firm, customers do this role in its customer orientation. This paper proposes that through an identification process; that is, they identify with customer orientation is directly influenced by corporate the firm or brand (e.g., Battacharya and Sen 2003; identity. When a firm’s identity influences its customer McAlexander and Schouten, Koening 2002, Algesheimer, orientation, firm performance will be positively impacted. Dholakia and Herrmann 2005), and see value in that An historical analysis shows three phases of Apple, Inc.’s corporate identity and relationship. While a customer life during which its identity influences customer orientation establishes a focus on customers, there are many orientation; then where Apple loses sight of its original different ways and directions that a customer focus can go. -

A Day in the Life of Your Data

A Day in the Life of Your Data A Father-Daughter Day at the Playground April, 2021 “I believe people are smart and some people want to share more data than other people do. Ask them. Ask them every time. Make them tell you to stop asking them if they get tired of your asking them. Let them know precisely what you’re going to do with their data.” Steve Jobs All Things Digital Conference, 2010 Over the past decade, a large and opaque industry has been amassing increasing amounts of personal data.1,2 A complex ecosystem of websites, apps, social media companies, data brokers, and ad tech firms track users online and offline, harvesting their personal data. This data is pieced together, shared, aggregated, and used in real-time auctions, fueling a $227 billion-a-year industry.1 This occurs every day, as people go about their daily lives, often without their knowledge or permission.3,4 Let’s take a look at what this industry is able to learn about a father and daughter during an otherwise pleasant day at the park. Did you know? Trackers are embedded in Trackers are often embedded Data brokers collect and sell, apps you use every day: the in third-party code that helps license, or otherwise disclose average app has 6 trackers.3 developers build their apps. to third parties the personal The majority of popular Android By including trackers, developers information of particular individ- and iOS apps have embedded also allow third parties to collect uals with whom they do not have trackers.5,6,7 and link data you have shared a direct relationship.3 with them across different apps and with other data that has been collected about you. -

Apple Co-Founder Steve Wozniak Announced As Xtuple Conference Opener

Apple Co-Founder Steve Wozniak Announced as xTuple Conference Opener Open source software leader partners with oldest speakers' forum in the U.S. NORFOLK, VA - June 16, 2014 — xTuple CEO Ned Lilly announced today that pass-holders to the company’s “ultimate user conference” will enjoy the legendary Steve Wozniak, co-founder of Apple (http://www.woz.org/) , as opening VIP keynote speaker, thanks to a partnership with The Norfolk Forum (http://thenorfolkforum.org/) . Scheduled for Monday, October 13, through Saturday, October 18, #xTupleCon14 moves this year to the premier downtown Norfolk Marriott Waterside Hotel and Conference Center. Conference Opener: Tuesday, October 14, at Chrysler Hall, 7:30 p.m. Steve Wozniak, Apple Inc. Founder, Silicon Valley Icon and Philanthropist Steve Wozniak helped shape the computing industry with his design of Apple's first line of products – the Apple I and II – and influenced the popular Macintosh. In 1976, Wozniak and Steve Jobs founded Apple Computer, Inc., with Wozniak's Apple I personal computer. The following year, he introduced his Apple II personal computer, featuring a central processing unit, a keyboard, color graphics, and a floppy disk drive. The Apple II was integral in launching the personal computer industry Wozniak currently serves as Chief Scientist for the in-memory hardware company Fusion-io and is a published author with the release of his New York Times best-selling autobiography, iWoz: From Computer Geek to Cult Icon, in September 2006 by Norton Publishing. xTuple has a lifelong affiliation with Apple products, including desktops, MacBooks, iPhones and iPads. Users of xTuple ERP are three times more likely to be running Apple products than the average business user. -

Apple Tv: Guess What's in the Box

APPLE TV: GUESS WHAT'S IN THE BOX Jacob, Phil. The Daily Telegraph 10 Nov 2012: 46. Full Text THE TECHNOLOGY GIANT HAS ALREADY REVOLUTIONISED OUR LIVES. NOW IT IS SET TO CHANGE THE VERY CONCEPT OF TELEVISION, WRITES PHIL JACOB It's not a nice, simple story that Apple is going to come in and turn the world upside down and we'll all live happily ever after We live in a world where you use your iPhone to make calls, check your iPad for the news before going to work and sitting down in front of your iMac. Still haven't had your fill of Apple yet? Try downloading a song on iTunes before going for a run -- while listening to your iPod. Over the past 36 years, Apple has dominated and revolutionised our lives like no company in history. But the tech giant has perhaps its biggest revolution still waiting in the wings -- a complete and radical overhaul of the television industry. Speculation about an Apple TV has been rife since the publication of Steve Jobs' biography last year. The Apple co-founder, who died on October 5, 2011, told his biographer Walter Isaacson he had "cracked" the problem of television, although Isaacson did not reveal the plans as the product has not been launched. Late last year industry sources were quoted as saying that Apple would launch 81cm and 94cm TV sets some time this year. "Two people briefed on the matter said the technology involved could ultimately be embedded in a television," The Wall Street Journal reported. -

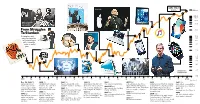

From Struggles to Stardom

AAPL 175.01 Steve Jobs 12/21/17 $200.0 100.0 80.0 17 60.0 Apple co-founders 14 Steve Wozniak 40.0 and Steve Jobs 16 From Struggles 10 20.0 9 To Stardom Jobs returns Following its volatile 11 10.0 8.0 early years, Apple has 12 enjoyed a prolonged 6.0 period of earnings 15 and stock market 5 4.0 gains. 2 7 2.0 1.0 1 0.8 4 13 1 6 0.6 8 0.4 0.2 3 Chart shown in logarithmic scale Tim Cook 0.1 1980 ’82 ’84 ’86’88 ’90 ’92 ’94 ’96 ’98 ’00 ’02 ’04 ’06’08 ’10 ’12 ’14 ’16 2018 Source: FactSet Dec. 12, 1980 (1) 1984 (3) 1993 (5) 1998 (8) 2003 2007 (12) 2011 2015 (16) Apple, best known The Macintosh computer Newton, a personal digital Apple debuts the iMac, an The iTunes store launches. Jobs announces the iPhone. Apple becomes the most valuable Apple Music, a subscription for the Apple II home launches, two days after assistant, launches, and flops. all-in-one desktop computer 2004-’05 (10) Apple releases the Apple TV publicly traded company, passing streaming service, launches. and iPod Touch, and changes its computer, goes public. Apple’s iconic 1984 1995 (6) with a colorful, translucent Apple unveils the iPod Mini, Exxon Mobil. Apple introduces 2017 (17 ) name from Apple Computer. Shares rise more than Super Bowl commercial. Microsoft introduces Windows body designed by Jony Ive. Shuffle, and Nano. the iPhone 4S with Siri. Tim Cook Introduction of the iPhone X.