Grammaticalization of Allocutivity Markers in Japanese and Korean in a Cross-Linguistic Perspective Anton Antonov

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The University of Chicago Tears in the Imperial Screen

THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO TEARS IN THE IMPERIAL SCREEN: WARTIME COLONIAL KOREAN CINEMA, 1936-1945 A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE DIVISION OF THE HUMANITIES IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY DEPARTMENT OF EAST ASIAN LANGUAGES AND CIVILIZATIONS BY HYUN HEE PARK CHICAGO, ILLINOIS AUGUST 2017 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page LIST OF TABLES ...…………………..………………………………...……… iii LIST OF FIGURES ...…………………………………………………..……….. iv ABSTRACT ...………………………….………………………………………. vi CHAPTER 1 ………………………..…..……………………………………..… 1 INTRODUCTION CHAPTER 2 ……………………………..…………………….……………..… 36 ENLIGHTENMENT AND DISENCHANTMENT: THE NEW WOMAN, COLONIAL POLICE, AND THE RISE OF NEW CITIZENSHIP IN SWEET DREAM (1936) CHAPTER 3 ……………………………...…………………………………..… 89 REJECTED SINCERITY: THE FALSE LOGIC OF BECOMING IMPERIAL CITIZENS IN THE VOLUNTEER FILMS CHAPTER 4 ………………………………………………………………… 137 ORPHANS AS METAPHOR: COLONIAL REALISM IN CH’OE IN-GYU’S CHILDREN TRILOGY CHAPTER 5 …………………………………………….…………………… 192 THE PLEASURE OF TEARS: CHOSŎN STRAIT (1943), WOMAN’S FILM, AND WARTIME SPECTATORSHIP CHAPTER 6 …………………………………………….…………………… 241 CONCLUSION BIBLIOGRAPHY …………………………………………………………….. 253 FILMOGRAPHY OF EXTANT COLONIAL KOREAN FILMS …………... 265 ii LIST OF TABLES Page Table 1. Newspaper articles regarding traffic film screening events ………....…54 Table 2. Newspaper articles regarding traffic film production ……………..….. 56 iii LIST OF FIGURES Page Figure. 1-1. DVDs of “The Past Unearthed” series ...……………..………..…..... 3 Figure. 1-2. News articles on “hygiene film screening” in Maeil sinbo ….…... 27 Figure. 2-1. An advertisement for Sweet Dream in Maeil sinbo……………… 42 Figure. 2-2. Stills from Sweet Dream ………………………………………… 59 Figure. 2-3. Stills from the beginning part of Sweet Dream ………………….…65 Figure. 2-4. Change of Ae-sun in Sweet Dream ……………………………… 76 Figure. 3-1. An advertisement of Volunteer ………………………………….. 99 Figure. 3-2. Stills from Volunteer …………………………………...……… 108 Figure. -

Deixis and Reference Tracing in Tsova-Tush (PDF)

DEIXIS AND REFERENCE TRACKING IN TSOVA-TUSH A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAIʻI AT MĀNOA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN LINGUISTICS MAY 2020 by Bryn Hauk Dissertation committee: Andrea Berez-Kroeker, Chairperson Alice C. Harris Bradley McDonnell James N. Collins Ashley Maynard Acknowledgments I should not have been able to finish this dissertation. In the course of my graduate studies, enough obstacles have sprung up in my path that the odds would have predicted something other than a successful completion of my degree. The fact that I made it to this point is a testament to thekind, supportive, wise, and generous people who have picked me up and dusted me off after every pothole. Forgive me: these thank-yous are going to get very sappy. First and foremost, I would like to thank my Tsova-Tush host family—Rezo Orbetishvili, Nisa Baxtarishvili, and of course Tamar and Lasha—for letting me join your family every summer forthe past four years. Your time, your patience, your expertise, your hospitality, your sense of humor, your lovingly prepared meals and generously poured wine—these were the building blocks that supported all of my research whims. My sincerest gratitude also goes to Dantes Echishvili, Revaz Shankishvili, and to all my hosts and friends in Zemo Alvani. It is possible to translate ‘thank you’ as მადელ შუნ, but you have taught me that gratitude is better expressed with actions than with set phrases, sofor now I will just say, ღაზიშ ხილჰათ, ბედნიერ ხილჰათ, მარშმაკიშ ხილჰათ.. -

Unexpected Nasal Consonants in Joseon-Era Korean Thomas

Unexpected Nasal Consonants in Joseon-Era Korean Thomas Darnell 17 April 2020 The diminutive suffixes -ngaji and -ngsengi are unique in contemporary Korean in that they both begin with the velar nasal consonant (/ŋ/) and seem to be of Korean origin. Surprisingly, they seem to share no direct genetic affiliation. But by reverse-engineering sound change involving the morpheme-initial velar nasal in the Ulsan dialect, I prove that the historical form of -aengi was actually maximally -ng; thus the suffixes -ngaji and -ngsaengi are related if we consider them to be concatenations of this diminutive suffix -ng and the suffixes -aji and -sengi. This is supported by the existence of words with the -aji suffix in which the initial velar nasal -ㅇ is absent and which have no semantic meaning of diminutiveness. 1. Introduction Korean is a language of contested linguistic origin spoken primarily on the Korean Peninsula in East Asia. There are approximately 77 million Korean speakers globally, though about 72 million of these speakers reside on the Korean peninsula (Eberhard et al.). Old Korean is the name given to the first attested stage of the Koreanic family, referring to the language spoken in the Silla kingdom, a small polity at the southeast end of the Korean peninsula. It is attested (at first quite sparsely) from the fifth century until the overthrow of the Silla state in the year 935 (Lee & Ramsey 2011: 48, 50, 55). Soon after that year, the geographic center of written Korean then moved to the capital of this conquering state, the Goryeo kingdom, located near present-day Seoul; this marks the beginning of Early Middle Korean (Lee & Ramsey: 50, 77). -

Sijo: Korean Poetry Form

Kim Leng East Asia: Origins to 1800 Spring 2019 Curriculum Project Sijo: Korean Poetry Form Rationale: This unit will introduce students to the sijo, a Korean poetic form, that predates the haiku. This popular poetic form has been written in Korea since the Choson dynasty (1392-1910). The three line poem is part of Korea’s rich cultural and literary heritage. Common Core English Language Art Standards: CCSS.ELA-Literacy.RL.9-10.4 Determine the meaning of words and phrases as they are used in the text, including figurative and connotative meanings; analyze the cumulative impact of specific word choices on meaning and tone (e.g., how the language evokes a sense of time and place; how it sets a formal or informal tone). CCSS.ELA-Literacy.RL.9-10.6 Analyze a particular point of view or cultural experience reflected in a work of literature from outside the United States, drawing on a wide reading of world literature. CCSS.ELA-Literacy.RL.9-10.10 By the end of grade 9, read and comprehend literature, including stories, dramas, and poems, in the grades 9-10 text complexity band proficiently, with scaffolding as needed at the high end of the range. Common Core Standards: L 3 Apply knowledge of language to understand how language functions in different contexts. L 5 Demonstrate understanding of figurative language, word relationships and nuances in meaning. English Language Arts Standards » Standard 10: Range, Quality, & Complexity » Range of Text Types for 6-12 Students in grades 6-12 apply the Reading standards to the following range of text types, with texts selected from a broad range of cultures and periods. -

UC Santa Cruz UC Santa Cruz Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC Santa Cruz UC Santa Cruz Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title The Historical Development of Initial Accent in Trimoraic Nouns in Kyoto Japanese Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/3f57b731 Author Angeles, Andrew Publication Date 2019 License https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ 4.0 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA SANTA CRUZ THE HISTORICAL DEVELOPMENT OF INITIAL ACCENT IN TRIMORAIC NOUNS IN KYOTO JAPANESE A thesis submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS in LINGUISTICS by Andrew Angeles September 2019 The thesis of Andrew Angeles is approved: _______________________________ Professor Junko Ito, Chair _______________________________ Associate Professor Ryan Bennett _______________________________ Associate Professor Grant McGuire _______________________________ Quentin Williams Acting Vice Provost and Dean of Graduate Studies Copyright © by Andrew Angeles 2019 TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Figures ............................................................................................................. v Abstract ...................................................................................................................... ix Acknowledgments ................................................................................................... xiv 1 Introduction .......................................................................................................... -

Christian Communication and Its Impact on Korean Society : Past, Present and Future Soon Nim Lee University of Wollongong

University of Wollongong Thesis Collections University of Wollongong Thesis Collection University of Wollongong Year Christian communication and its impact on Korean society : past, present and future Soon Nim Lee University of Wollongong Lee, Soon Nim, Christian communication and its impact on Korean society : past, present and future, Doctor of Philosphy thesis, School of Journalism and Creative Writing - Faculty of Creative Arts, University of Wollongong, 2009. http://ro.uow.edu.au/theses/3051 This paper is posted at Research Online. Christian Communication and Its Impact on Korean Society: Past, Present and Future Thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the award of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Wollongong Soon Nim Lee Faculty of Creative Arts School of Journalism & Creative writing October 2009 i CERTIFICATION I, Soon Nim, Lee, declare that this thesis, submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the award of Doctor of Philosophy, in the Department of Creative Arts and Writings (School of Journalism), University of Wollongong, is wholly my own work unless otherwise referenced or acknowledged. The document has not been submitted for qualifications at any other academic institution. Soon Nim, Lee 18 March 2009. i Table of Contents Certification i Table of Contents ii List of Tables vii Abstract viii Acknowledgements x Chapter 1: Introduction 1 Chapter 2: Christianity awakens the sleeping Hangeul 12 Introduction 12 2.1 What is the Hangeul? 12 2.2 Praise of Hangeul by Christian missionaries -

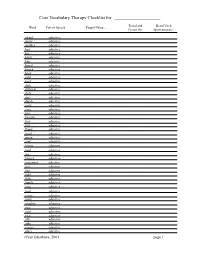

250 Word List

Core Vocabulary Therapy Checklist for ____________________ Tested and Heard Used Word Part of Speech Taught Using ... Passed On: Spontaneously: afraid adjective angry adjective another adjective bad adjective big adjective black adjective blue adjective bored adjective brown adjective busy adjective cold adjective cool adjective dark adjective different adjective dirty adjective dry adjective dumb adjective early adjective easy adjective fast adjective favorite adjective first adjective full adjective funny adjective good adjective green adjective grey adjective happy adjective hard adjective hot adjective hungry adjective important adjective last adjective late adjective light adjective little adjective lonely adjective long adjective mad adjective many adjective more adjective naughty adjective new adjective next adjective nice adjective old adjective only adjective orange adjective other adjective ©VanTatenhove, 2001 page 1 Core Vocabulary Therapy Checklist for ____________________ Word Part of Speech Taught Using ... Tested and Heard Used Passed On: Spontaneously: pink adjective purple adjective real adjective red adjective right adjective sad adjective same adjective sick adjective silly adjective sure adjective thirsty adjective tired adjective wet adjective white adjective wrong adjective yellow adjective adjective adjective adjective again adverb all right adverb almost adverb already adverb always adverb away adverb backwards adverb forward adverb here adverb indoors adverb just adverb maybe adverb much adverb never adverb not -

Remarks on the History of the Indo-European Infinitive Dorothy Disterheft University of South Carolina - Columbia, [email protected]

University of South Carolina Scholar Commons Faculty Publications Linguistics, Program of 1981 Remarks on the History of the Indo-European Infinitive Dorothy Disterheft University of South Carolina - Columbia, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/ling_facpub Part of the Linguistics Commons Publication Info Published in Folia Linguistica Historica, Volume 2, Issue 1, 1981, pages 3-34. Disterheft, D. (1981). Remarks on the History of the Indo-European Infinitive. Folia Linguistica Historica, 2(1), 3-34. DOI: 10.1515/ flih.1981.2.1.3 © 1981 Societas Linguistica Europaea. This Article is brought to you by the Linguistics, Program of at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Foli.lAfl//ui.tfcoFolia Linguistica HfltorlcGHistorica II/III/l 'P'P.pp. 8-U3—Z4 © 800£etruSocietae lAngu,.ticaLinguistica Etlropaea.Evropaea, 1981lt)8l REMARKSBEMARKS ONON THETHE HISTORYHISTOKY OFOF THETHE INDO-EUROPEANINDO-EUROPEAN INFINITIVEINFINITIVE i DOROTHYDOROTHY DISTERHEFTDISTERHEFT I 1.1. INTRODUCTIONINTRODUCTION WithWith thethe exceptfonexception ofof Indo-IranianIndo-Iranian (Ur)(Hr) andand CelticCeltic allall historicalhistorical Indo-EuropeanIndo-European (IE)(IE) subgroupssubgroups havehave a morphologicalIymorphologically distinctdistinct II infinitive.Infinitive. However,However, nono singlesingle proto-formproto-form cancan bebe reconstructedreconstructed -

The Finnish Korean Connection: an Initial Analysis

The Finnish Korean Connection: An Initial Analysis J ulian Hadland It has traditionally been accepted in circles of comparative linguistics that Finnish is related to Hungarian, and that Korean is related to Mongolian, Tungus, Turkish and other Turkic languages. N.A. Baskakov, in his research into Altaic languages categorised Finnish as belonging to the Uralic family of languages, and Korean as a member of the Altaic family. Yet there is evidence to suggest that Finnish is closer to Korean than to Hungarian, and that likewise Korean is closer to Finnish than to Turkic languages . In his analytic work, "The Altaic Family of Languages", there is strong evidence to suggest that Mongolian, Turkic and Manchurian are closely related, yet in his illustrative examples he is only able to cite SIX cases where Korean bears any resemblance to these languages, and several of these examples are not well-supported. It was only in 1927 that Korean was incorporated into the Altaic family of languages (E.D. Polivanov) . Moreover, as Baskakov points out, "the Japanese-Korean branch appeared, according to (linguistic) scien tists, as a result of mixing altaic dialects with the neighbouring non-altaic languages". For this reason many researchers exclude Korean and Japanese from the Altaic family. However, the question is, what linguistic group did those "non-altaic" languages belong to? If one is familiar with the migrations of tribes, and even nations in the first five centuries AD, one will know that the Finnish (and Ugric) tribes entered the areas of Eastern Europe across the Siberian plane and the Volga. -

Navajo Verb Stem Position and the Bipartite Structure of the Navajo

678 REMARKSANDREPLIES NavajoVerb Stem Positionand the BipartiteStructure of the NavajoConjunct Sector Ken Hale TheNavajo verb stem appears at the rightmost edge of the verb word. Innumerouscases it forms a lexicalconstituent with a preverb,occur- ringat theleftmost edge of thesurface verb word, much in themanner ofDutchand German verb-particle arrangements in verb-secondfinite clauses.In Navajothe initial and finalpositions are separated by eight morphemeorder ‘ ‘slots’’ recognizedin the Athabaskan literature (and describedin detail for Navajo in Young and Morgan 1987). A phono- logicalsolution to this and a numberof otherdeep-surface disparities isexploredhere, based on theinsights of earlierworks on theNavajo verb,including Speas 1984, 1990, McDonough 1996, 2000, and Rice 1989, 2000. Keywords: verbmorphology, morphosyntactic disparity, spell-out, Navajo,Athabaskan 1Verb Stem Position TheNavajo verb stem forms asinglelexical constituent with the prefixal, particle-like category called preverb inthe Athabaskan linguistic literature (see Rice2000). However, like particle- verbcombinations in Dutchand German verb-second clauses, the parts of thisconstituent in the Navajocounterpart are separated in the surface forms ofverbal projections in syntax. In the Navajoversion of thisarrangement, the preverb occupies the leftmost position in the verb word, andthe verb stem occupies the rightmost position. TheNavajo verb in (1) canbe used to illustrate the phenomenon. The verb is segmented intoits various parts in (2), and the components are identified in slightly greater detail in (3). (1) Sila´o t’o´o´’go´o´ ch’´õ shidinõ´daøzh.(Young and Morgan 1987:283) ‘Thepoliceman jerked me outdoors (to get me out of afight).’ (2) ch’´õ sh d n-´ daøzh PreverbObject Qualifier Mode/ SubjVoice V (stem) Iwishto dedicate thisarticle totheNavajo Language Academy, asmall groupof linguists and teachers devotedto Navajolanguage research andeducation. -

Unity and Diversity in Grammaticalization Scenarios

Unity and diversity in grammaticalization scenarios Edited by Walter Bisang Andrej Malchukov language Studies in Diversity Linguistics 16 science press Studies in Diversity Linguistics Chief Editor: Martin Haspelmath In this series: 1. Handschuh, Corinna. A typology of marked-S languages. 2. Rießler, Michael. Adjective attribution. 3. Klamer, Marian (ed.). The Alor-Pantar languages: History and typology. 4. Berghäll, Liisa. A grammar of Mauwake (Papua New Guinea). 5. Wilbur, Joshua. A grammar of Pite Saami. 6. Dahl, Östen. Grammaticalization in the North: Noun phrase morphosyntax in Scandinavian vernaculars. 7. Schackow, Diana. A grammar of Yakkha. 8. Liljegren, Henrik. A grammar of Palula. 9. Shimelman, Aviva. A grammar of Yauyos Quechua. 10. Rudin, Catherine & Bryan James Gordon (eds.). Advances in the study of Siouan languages and linguistics. 11. Kluge, Angela. A grammar of Papuan Malay. 12. Kieviet, Paulus. A grammar of Rapa Nui. 13. Michaud, Alexis. Tone in Yongning Na: Lexical tones and morphotonology. 14. Enfield, N. J (ed.). Dependencies in language: On the causal ontology of linguistic systems. 15. Gutman, Ariel. Attributive constructions in North-Eastern Neo-Aramaic. 16. Bisang, Walter & Andrej Malchukov (eds.). Unity and diversity in grammaticalization scenarios. ISSN: 2363-5568 Unity and diversity in grammaticalization scenarios Edited by Walter Bisang Andrej Malchukov language science press Walter Bisang & Andrej Malchukov (eds.). 2017. Unity and diversity in grammaticalization scenarios (Studies in Diversity Linguistics -

Origins of the Japanese Languages. a Multidisciplinary Approach”

MASTERARBEIT / MASTER’S THESIS Titel der Masterarbeit / Title of the Master’s Thesis “Origins of the Japanese languages. A multidisciplinary approach” verfasst von / submitted by Patrick Elmer, BA angestrebter akademischer Grad / in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts (MA) Wien, 2019 / Vienna 2019 Studienkennzahl lt. Studienblatt / A 066 843 degree programme code as it appears on the student record sheet: Studienrichtung lt. Studienblatt / Masterstudium Japanologie UG2002 degree programme as it appears on the student record sheet: Betreut von / Supervisor: Mag. Dr. Bernhard Seidl Mitbetreut von / Co-Supervisor: Dr. Bernhard Scheid Table of contents List of figures .......................................................................................................................... v List of tables ........................................................................................................................... v Note to the reader..................................................................................................................vi Abbreviations ....................................................................................................................... vii 1. Introduction ................................................................................................................. 1 1.1. Research question ................................................................................................. 1 1.2. Methodology ........................................................................................................