Download Full PDF Version

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rey, J.C. and Cort, J.L. 1978. Nota Sobre Los Primeros Resultados De La Campaña De Marcado De Túnidos Frente Al Litoral De Castellón

110 Rey, J.C. and Cort, J.L. 1978. Nota sobre los primeros resultados de la campaña de marcado de túnidos frente al litoral de Castellón. Bol. Inst. Esp. Oceanogr. 4 (3): 140–142 Rey, J.C. and Cort, J.L. 1981. Contribution à la connaissance de la migration des Scombridae en Méditerranée Occidentale. Rapp. P-V, Commn. Int. Explor. Scient. Mer Méditerr., 27: 97–98. Rey, J.C., Alot, E. and Ramos, A. 1984. Sinopsis biológica del bonito, Sarda sarda (Bloch), del Mediterráneo y Atlántico Este. Iccat, Coll. Vol. Sci. Pap. 20(2): 469–502. Rey, J.C., Alot, E. and Ramos, A. 1986. Growth of the Atlantic bonito (Sarda sarda Bloch, 1793) in the Atlantic and Mediterranean area of the Strait of Gibraltar. Inv. Pesq. 50 (2): 179–185. Robert, M. and Roesti. 1966. The Declining Economic Role of the Mediterranean Tuna Fishery American Journal of Economics and Sociology 25 (1), 77–90. Rodriguez Roda, J. 1966. Estudio de la bacoreta, Euthynnus alleteratus (Raf.) bonito, Sarda sarda (Bloch) y melva, Auxis thazard (Lac.), capturados por las almadrabas españolas. Inv. Pesq. 30: 247–292. Rodriguez Roda, J. 1981. Estudio de la edad y crecimiento del bonito, Sarda sarda (Block), de la costa sudatlantica de España. Inv. Pesq. 45(1):181–186. Rodriguez Roda, J. 1983. Edad y crecimiento de la melva, Auxis rochei (Risso), del Sur de España. Invest. Pesq. (Barc.), 47 (3): 397–402. Sabatés, A. and Recasens, L. 2001. Seasonal distribution and spawning of small tunas, Auxis rochei (Risso) and Sarda sarda (Bloch) in the northwestern Mediterranean. -

NOTE on the Fishery and Some Aspects of the Biology of Dogtooth Tuna, Gymnosarda Unicolor (Ruppell)From Minicoy, Lakshadweep

I. mar. biol. Ass. India, 47 (1) : 111 - 113, Jan. - June, 2005 NOTE On the fishery and some aspects of the biology of dogtooth tuna, Gymnosarda unicolor (Ruppell)from Minicoy, Lakshadweep M.Sivadas and A.Anasukoya Research Centre of Central Marine Fisheries Research Institute, Calicut - 673 005, India Abstract The results of a study, on the fishery and biology of dogtooth tuna, Gymnosarda unicolor (Ruppell), conducted at Minicoy during 1995 to 1999 are presented. The resource is exploited from around the reef areas during July-August or September for sustenance when the usual fishing activities like pole and line and trolling are suspended. The total catch in a season varied from 56 to 481 kg. The size ranged from 44 to 126 cm fork length with the modal group at 58 and 62 cm. The length-weight relationship was found to be Log W = -4.5337 + 2.77 Log L. Fish below 70 cm size was found to be immature. The dogtooth tuna, Gymnosarda unicolor Material and methods (Ruppell) is a tropical Indo-Pacific epipe- Data on catch and biological aspects lagic species usually found around coral such as length, weight, feeding condition, reefs. In India, they are reported from maturity, etc were collected almost on a Andaman-Nicobar and from daily basis at the landing centre itself Lakshadweep Islands (Silas and Pillai, during each season. The entrails of the 1982). In Lakshadweep, they are not fishes are removed at the landing centre exploited by pole and line and troll line but are caught regularly, though in few itself before they are taken home. -

Do Some Atlantic Bluefin Tuna Skip Spawning?

SCRS/2006/088 Col. Vol. Sci. Pap. ICCAT, 60(4): 1141-1153 (2007) DO SOME ATLANTIC BLUEFIN TUNA SKIP SPAWNING? David H. Secor1 SUMMARY During the spawning season for Atlantic bluefin tuna, some adults occur outside known spawning centers, suggesting either unknown spawning regions, or fundamental errors in our current understanding of bluefin tuna reproductive schedules. Based upon recent scientific perspectives, skipped spawning (delayed maturation and non-annual spawning) is possibly prevalent in moderately long-lived marine species like bluefin tuna. In principle, skipped spawning represents a trade-off between current and future reproduction. By foregoing reproduction, an individual can incur survival and growth benefits that accrue in deferred reproduction. Across a range of species, skipped reproduction was positively correlated with longevity, but for non-sturgeon species, adults spawned at intervals at least once every two years. A range of types of skipped spawning (constant, younger, older, event skipping; and delays in first maturation) was modeled for the western Atlantic bluefin tuna population to test for their effects on the egg-production-per-recruit biological reference point (stipulated at 20% and 40%). With the exception of extreme delays in maturation, skipped spawning had relatively small effect in depressing fishing mortality (F) threshold values. This was particularly true in comparison to scenarios of a juvenile fishery (ages 4-7), which substantially depressed threshold F values. Indeed, recent F estimates for 1990-2002 western Atlantic bluefin tuna stock assessments were in excess of threshold F values when juvenile size classes were exploited. If western bluefin tuna are currently maturing at an older age than is currently assessed (i.e., 10 v. -

DYNAMIC HABITAT USE of ALBACORE and THEIR PRIMARY PREY SPECIES in the CALIFORNIA CURRENT SYSTEM Calcofi Rep., Vol

MUHLING ET AL.: DYNAMIC HABITAT USE OF ALBACORE AND THEIR PRIMARY PREY SPECIES IN THE CALIFORNIA CURRENT SYSTEM CalCOFI Rep., Vol. 60, 2019 DYNAMIC HABITAT USE OF ALBACORE AND THEIR PRIMARY PREY SPECIES IN THE CALIFORNIA CURRENT SYSTEM BARBARA MUHLING, STEPHANIE BRODIE, MICHAEL JACOX OWYN SNODGRASS, DESIREE TOMMASI NOAA Earth System Research Laboratory University of California, Santa Cruz Boulder, CO Institute for Marine Science Santa Cruz, CA CHRISTOPHER A. EDWARDS ph: (858) 546-7197 Ocean Sciences Department [email protected] University of California, Santa Cruz, CA BARBARA MUHLING, OWYN SNODGRASS, YI XU HEIDI DEWAR, DESIREE TOMMASI, JOHN CHILDERS Department of Fisheries and Oceans NOAA Southwest Fisheries Science Center Delta, British Columbia, Canada San Diego, CA STEPHANIE SNYDER STEPHANIE BRODIE, MICHAEL JACOX Thomas More University, NOAA Southwest Fisheries Science Center Crestview Hills, KY Monterey, CA ABSTRACT peiods, krill, and some cephalopods (Smith et al. 2011). Juvenile north Pacific albacore Thunnus( alalunga) for- Many of these forage species are fished commercially, age in the California Current System (CCS), supporting but also support higher-order predators further up the fisheries between Baja California and British Columbia. food chain, such as other exploited species (e.g., tunas, Within the CCS, their distribution, abundance, and for- billfish) and protected resources (e.g., marine mammals aging behaviors are strongly variable interannually. Here, and seabirds) (Pikitch et al. 2004; Link and Browman we use catch logbook data and trawl survey records to 2014). Effectively managing marine ecosystems to pre- investigate how juvenile albacore in the CCS use their serve these trophic linkages, and improve robustness of oceanographic environment, and how their distributions management strategies to environmental variability, thus overlap with the habitats of four key forage species. -

India's National Report to the Scientific Committee of the Indian Ocean

IOTC–2015–SC18–NR09[E] India’s National Report to the Scientific Committee of the Indian Ocean Tuna Commission’2015 Premchand, L. Ramalingam, A. Tiburtius, A. Siva, Ansuman Das, Rajashree B Sanadi and Rahul Kumar B Tailor Fishery Survey of India Government of India, Botawala Chambers, Sir. P. M. Road, Mumbai 0 INFORMATION OF FISHERIES, RESEARCH AND STATISTICS In accordance with IOTC Resolution 15/02, final YES scientific data for the previous year was Communication F.No.43-6/2014 Fy. II, dated provided to the Secretariat by June of the 03/07/2015 to the Ministry of Agriculture and current year, for all fleets other than Farmer’s Welfare, New Delhi. longline(e.g., for a National report submitted to the Secretariat in 2015, final data for the 2014 Calendar year must be provided to the Secretariat by 30 June’2015) In accordance with IOTC Resolution 15/02, YES provisional longline data for the previous year Communication F.No.43-6/2014 Fy.II, was provided to the Secretariat by 30 June of 03/07/2015 to the Ministry of Agriculture and the current year (e.g., for a National report Farmer’s Welfare, New Delhi. submitted to the Secretariat in 2015, final data for the 2014 Calendar year must be provided to the Secretariat by 30 June’2015) Reminder: Final longline data for the previous year is due to the Secretariat by 30 December of the current year (e.g., for a National report submitted to the Secretariat in 2015, final data for the 2014 Calendar year must be provided to the Secretariat by 30 June’2015) If no, please indicate the reason(s) and intended actions: - Executive Summary Tuna and tuna like fishes are one of the components of pelagic resources. -

Atlantic Bluefin Tuna (Thunnus Thynnus) Population Dynamics

Environ. Sci. Technol. 2009, 43, 8522–8527 nations of the International Commission for the Conservation Atlantic Bluefin Tuna (Thunnus of Atlantic Tunas (ICCAT) currently manage ABFT fisheries thynnus) Population Dynamics assuming two units (a western stock spawning in the Gulf of Mexico, and an eastern stock which spawns in the Delineated by Organochlorine Mediterranean Sea) ostensibly separated by the 45° W meridian with little intermixing between stocks. However, Tracers tagging studies indicate that bluefin tuna undergo extensive and complex migrations, including trans-Atlantic migrations, ,† and that stock mixing could be as high as 30% (2-4). Extensive REBECCA M. DICKHUT,* - ASHOK D. DESHPANDE,‡ mixing of eastern and western stocks (35 57% bluefin tuna ALESSANDRA CINCINELLI,§ of eastern origin) within the U.S. Mid Atlantic Bight was also 18 MICHELE A. COCHRAN,† reported recently based on otolith δ O values (5). The SIMONETTA CORSOLINI,| uncertainty of stock structures due to mixing makes it difficult RICHARD W. BRILL,† DAVID H. SECOR,⊥ for fisheries managers to assess the effectiveness of rebuilding AND JOHN E. GRAVES† efforts for the dwindling western Atlantic spawning stock of Virginia Institute of Marine Science, Gloucester Point, bluefin tuna. Understanding ABFT spatial distributions and Virginia 23062, National Marine Fisheries Service, dynamics are vital for robust population assessments and Highlands, New Jersey 07732, Department of Chemistry, the design of effective management strategies, and there is University of Florence, 50019 -

Ottawa: Complete List of Seafood Samples

Ottawa: complete list of seafood samples Sold as Identified as (BOLD) Common name (CFIA Mislabelled Purchase (label/menu/server) market name) location Arctic char Salverus alpirus Arctic char (Arctic char, No Restaurant char) Arctic char Salverus alpirus Arctic char (Arctic char, No Restaurant char) Arctic char Salverus alpirus Arctic char (Arctic char, No Restaurant char) Arctic char Salverus alpirus Arctic char (Arctic char, No Grocery char) Store Butterfish Lepidocybium Escolar (Escolar, Snake Yes Restaurant flavobrunneum Mackerel) Cod, Fogo Island Gadus morhua Atlantic cod (Atlantic cod, No Restaurant cod) Cod, Atlantic Gadus morhua Atlantic cod (Atlantic cod, No Restaurant cod) Cod, Icelandic Gadus morhua Atlantic cod (Atlantic cod, No Restaurant cod) Cod, Atlantic Gadus morhua Atlantic cod (Atlantic cod, No Restaurant cod) (food truck) Cod, Atlantic Gadus macrocephalus Pacific cod (Pacific cod, cod) Yes Restaurant Cod, Pacific Micromesistius australis Southern blue whiting Yes Restaurant (Southern blue whiting, Blue whiting, Blue cod) Cod, Norwegian Gadus morhua Atlantic cod (Atlantic cod, No Restaurant cod) Cod, Atlantic Gadus morhua Atlantic cod (Atlantic cod, No Restaurant cod) Cod, Atlantic Gadus morhua Atlantic cod (Atlantic cod, No Restaurant cod) Cod, Alaskan Gadus macrocephalus Pacific cod (Pacific cod, cod) No Grocery Store Cod, Pacific Gadus macrocephalus Pacific cod (Pacific cod, cod) No Grocery Store Cod, North Atlantic Gadus macrocephalus Pacific cod (Pacific cod, cod) Yes Restaurant Cod Gadus macrocephalus Pacific cod (Pacific cod, cod) No Grocery Store Cod, Icelandic Gadus morhua Atlantic cod (Atlantic cod, No Grocery cod) Store Cod, Icelandic Gadus morhua Atlantic cod (Atlantic cod, No Grocery cod) Store Euro Bass Gadus morhua Atlantic cod (Atlantic cod, Yes Restaurant cod) Grouper Epinephelus diacanthus Spinycheek grouper (n/a) Yes – E. -

Status of Billfish Resources and the Billfish Fisheries in the Western

SLC/FIAF/C1127 (En) FAO Fisheries and Aquaculture Circular ISSN 2070-6065 STATUS OF BILLFISH RESOURCES AND BILLFISH FISHERIES IN THE WESTERN CENTRAL ATLANTIC Source: ICCAT (2015) FAO Fisheries and Aquaculture Circular No. 1127 SLC/FIAF/C1127 (En) STATUS OF BILLFISH RESOURCES AND BILLFISH FISHERIES IN THE WESTERN CENTRAL ATLANTIC by Nelson Ehrhardt and Mark Fitchett School of Marine and Atmospheric Science, University of Miami Miami, United States of America FOOD AND AGRICULTURE ORGANIZATION OF THE UNITED NATIONS Bridgetown, Barbados, 2016 The designations employed and the presentation of material in this information product do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) concerning the legal or development status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The mention of specific companies or products of manufacturers, whether or not these have been patented, does not imply that these have been endorsed or recommended by FAO in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. The views expressed in this information product are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of FAO. ISBN 978-92-5-109436-5 © FAO, 2016 FAO encourages the use, reproduction and dissemination of material in this information product. Except where otherwise indicated, material may be copied, downloaded and printed for private study, research and teaching purposes, or for use in non-commercial products or services, provided that appropriate DFNQRZOHGJHPHQWRI)$2DVWKHVRXUFHDQGFRS\ULJKWKROGHULVJLYHQDQGWKDW)$2¶VHQGRUVHPHQWRI XVHUV¶YLHZVSURGXFWVRUVHUYLFHVLVQRWLPSOLHGLQDQ\ZD\ All requests for translation and adaptation rights, and for resale and other commercial use rights should be made via www.fao.org/contact-us/licence-request or addressed to [email protected]. -

Estimating Age and Growth of Little Tunny, Euthynnus Alletteratus, Off the Coast of Senegal, Using Dorsal Fin Spine Sections

SUMMARY PAPER Estimating Age and Growth of Little Tunny, Euthynnus alletteratus, off the Coast of Senegal, Using Dorsal Fin Spine Sections PATRICE M. CAYRE 1 and TAIB DIOUP ABSTRACT Estimates of age were made from counts of growtb bands on dorsal spine sections of 491 little tunny, Euthynnus alletteratus, captured off the coast of Senegal during 1979. Analysis of marginal growtb bands (by montb) indicates that these bands are probably formed during tbe cold season (November-May). Mean size at estimated age was deter mined for tbe first 8 yr of life. These results, tbougb not validated, closely approximated other studies for young fisb (estimated ages 1-3), but were bigbly variable for older age categories. Tbe index of average percent error (E) for age nates from our study was 10.5% and infers good precision. RESUME r La determination de I'age de 491 thonines, Euthynnus alletteratus, a ele Iaite par complage des anneaux de croissaneesurdeseoupes transversales du premier rayon de la nageoire dorsale. L'analyse mensuelle de la nature du bord externe des coupes, Indique que les annuli (i.e., zones translucides) se Iormeraient au cours de la saison froide (novembre a mail. Les tailles moyennes correspondant aux ages de I a 8 ans sonl donnees, Usresultats, bien que non valides par d'autres metbodes, sont Ires voisins de ceux exposes dans d'autres travaux pour les ages de I a 3 ans; des differences non negligeables apparaissent cependant pour res poissons plus ages. L'index de pourcentage moyen d'erreur (E) entre les ages attribues par les deux auteurs est de 10.50/0ce qui indique une bonne precision de la methode utilisee, INTRODUCTION age of little tunny collected off Senegal by counting growth bands on sections of dorsal spines, 2) determine the time of Commercial tuna fisheries in the eastern tropical Atlantic band formation by analysis of marginal growth bandspine sec seem to have reached their maximum sustainable yield for tions, and 3) estimate the degree of precision (repeatability) of most species (ICCAT 1977-82). -

IATTC-94-01 the Tuna Fishery, Stocks, and Ecosystem in the Eastern

INTER-AMERICAN TROPICAL TUNA COMMISSION 94TH MEETING Bilbao, Spain 22-26 July 2019 DOCUMENT IATTC-94-01 REPORT ON THE TUNA FISHERY, STOCKS, AND ECOSYSTEM IN THE EASTERN PACIFIC OCEAN IN 2018 A. The fishery for tunas and billfishes in the eastern Pacific Ocean ....................................................... 3 B. Yellowfin tuna ................................................................................................................................... 50 C. Skipjack tuna ..................................................................................................................................... 58 D. Bigeye tuna ........................................................................................................................................ 64 E. Pacific bluefin tuna ............................................................................................................................ 72 F. Albacore tuna .................................................................................................................................... 76 G. Swordfish ........................................................................................................................................... 82 H. Blue marlin ........................................................................................................................................ 85 I. Striped marlin .................................................................................................................................... 86 J. Sailfish -

PROXIMATE and GENETIC ANALYSIS of BLACKFIN TUNA (T. Atlanticus)

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.11.03.366153; this version posted November 4, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. PROXIMATE AND GENETIC ANALYSIS OF BLACKFIN TUNA (T. atlanticus). Yuridia M. Núñez-Mata1, Jesse R. Ríos Rodríguez 1, Adriana L. Perales-Torres 1, Xochitl F. De la Rosa-Reyna2, Jesús A. Vázquez-Rodríguez 3, Nadia A. Fernández-Santos2, Humberto Martínez Montoya 1 * 1 Unidad Académica Multidisciplinaria Reynosa Aztlán – Universidad Autónoma de Tamaulipas. Reynosa, Tamaulipas. 2 Centro de Biotecnología Genómica – Instituto Politécnico Nacional. Reynosa, Tamaulipas. 3 Centro de Investigación en Salud Pública y Nutrición – Universidad Autónoma de Nuevo León. Monterrey, Nuevo León. *Correspondence: [email protected] ORCID: 0000-0003-3228-0054 bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.11.03.366153; this version posted November 4, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. ABSTRACT The tuna meat is a nutritious food that possesses high content of protein, its low content of saturated fatty acids makes it a high demand food in the world. The Thunnus genus is composed of eight species, albacore (T. alalunga), bigeye (T. obesus), long tail tuna (T. tonggol), yellowfin tuna (T. albacares), pacific bluefin tuna (T. orientalis), bluefin tuna (T. maccoyii), Atlantic bluefin tuna ( T. thynnus) and blackfin tuna (T. atlanticus). The blackfin tuna (BFT) (Thunnus atlanticus) represent the smallest species within the Thunnus genus. -

Among the World's Most Popular Game Fishes, Tunas Are Also

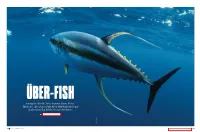

ÜBER-FISH Among the World’s Most Popular Game Fishes, Tunas Are Also Some of the Most Highly Evolved and Sophisticated of All the Ocean’s Predators BY DOUG OLANDER DANIEL GOEZ DANIEL 74 DECEMBER 2017 SPORTFISHINGMAG.COM 75 The Family Tree minimizes drag with a very low reduce the turbulence in the Tunas are part of the family drag coefficient,” optimizing effi- water ahead of the tail. Scombridae, which also includes cient swimming both at cruise Unlike most fishes with broad, mackerels, large and small. But and burst. While most fishes bend flexible tails that bend to scoop there are tunas, and then there their bodies side to side when water to move a fish forward, are, well, “true tunas.” moving forward, tunas’ bodies tunas derive tremendous That is, two groups don’t bend. They’re essentially thrust with thin, hard, lunate WHILE MOST FISHES BEND ( sometimes known as “tribes”) rigid, solid torpedoes. ( crescent-moon-shaped) tails dominate the tuna clan. One is And these torpedoes are that beat constantly, capable of THEIR BODIES SIDE TO SIDE Thunnini, which is the group perfectly streamlined, their 10 to 12 or more beats per second. considered true tunas, charac- larger fins fitting perfectly into That relentless thrust accounts WHEN MOVING FORWARD, terized by two separate dorsal grooves so no part of these fins for the unstoppable runs that fins and a relatively thick body. a number of highly specialized protrudes above the body surface. tuna make repeatedly when TUNAS’ BODIES DON’T BEND. The 15 species of Thunnini are features facilitate these They lack the convex eyes of hooked.