DYNAMIC HABITAT USE of ALBACORE and THEIR PRIMARY PREY SPECIES in the CALIFORNIA CURRENT SYSTEM Calcofi Rep., Vol

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ottawa: Complete List of Seafood Samples

Ottawa: complete list of seafood samples Sold as Identified as (BOLD) Common name (CFIA Mislabelled Purchase (label/menu/server) market name) location Arctic char Salverus alpirus Arctic char (Arctic char, No Restaurant char) Arctic char Salverus alpirus Arctic char (Arctic char, No Restaurant char) Arctic char Salverus alpirus Arctic char (Arctic char, No Restaurant char) Arctic char Salverus alpirus Arctic char (Arctic char, No Grocery char) Store Butterfish Lepidocybium Escolar (Escolar, Snake Yes Restaurant flavobrunneum Mackerel) Cod, Fogo Island Gadus morhua Atlantic cod (Atlantic cod, No Restaurant cod) Cod, Atlantic Gadus morhua Atlantic cod (Atlantic cod, No Restaurant cod) Cod, Icelandic Gadus morhua Atlantic cod (Atlantic cod, No Restaurant cod) Cod, Atlantic Gadus morhua Atlantic cod (Atlantic cod, No Restaurant cod) (food truck) Cod, Atlantic Gadus macrocephalus Pacific cod (Pacific cod, cod) Yes Restaurant Cod, Pacific Micromesistius australis Southern blue whiting Yes Restaurant (Southern blue whiting, Blue whiting, Blue cod) Cod, Norwegian Gadus morhua Atlantic cod (Atlantic cod, No Restaurant cod) Cod, Atlantic Gadus morhua Atlantic cod (Atlantic cod, No Restaurant cod) Cod, Atlantic Gadus morhua Atlantic cod (Atlantic cod, No Restaurant cod) Cod, Alaskan Gadus macrocephalus Pacific cod (Pacific cod, cod) No Grocery Store Cod, Pacific Gadus macrocephalus Pacific cod (Pacific cod, cod) No Grocery Store Cod, North Atlantic Gadus macrocephalus Pacific cod (Pacific cod, cod) Yes Restaurant Cod Gadus macrocephalus Pacific cod (Pacific cod, cod) No Grocery Store Cod, Icelandic Gadus morhua Atlantic cod (Atlantic cod, No Grocery cod) Store Cod, Icelandic Gadus morhua Atlantic cod (Atlantic cod, No Grocery cod) Store Euro Bass Gadus morhua Atlantic cod (Atlantic cod, Yes Restaurant cod) Grouper Epinephelus diacanthus Spinycheek grouper (n/a) Yes – E. -

California Sea Lion Interaction and Depredation Rates with the Commercial Passenger Fishing Vessel Fleet Near San Diego

HANAN ET AL.: SEA LIONS AND COMMERCIAL PASSENGER FISHING VESSELS CalCOFl Rep., Vol. 30,1989 CALIFORNIA SEA LION INTERACTION AND DEPREDATION RATES WITH THE COMMERCIAL PASSENGER FISHING VESSEL FLEET NEAR SAN DIEGO DOYLE A. HANAN, LISA M. JONES ROBERT B. READ California Department of Fish and Game California Department of Fish and Game c/o Southwest Fisheries Center 1350 Front Street, Room 2006 P.O. Box 271 San Diego, California 92101 La Jolla, California 92038 ABSTRACT anchovies, Engraulis movdax, which are thrown California sea lions depredate sport fish caught from the fishing boat to lure surface and mid-depth by anglers aboard commercial passenger fishing fish within casting range. Although depredation be- vessels. During a statewide survey in 1978, San havior has not been observed along the California Diego County was identified as the area with the coast among other marine mammals, it has become highest rates of interaction and depredation by sea a serious problem with sea lions, and is less serious lions. Subsequently, the California Department of with harbor seals. The behavior is generally not Fish and Game began monitoring the rates and con- appreciated by the boat operators or the anglers, ducting research on reducing them. The sea lion even though some crew and anglers encourage it by interaction and depredation rates for San Diego hand-feeding the sea lions. County declined from 1984 to 1988. During depredation, sea lions usually surface some distance from the boat, dive to swim under RESUMEN the boat, take a fish, and then reappear a safe dis- Los leones marinos en California depredan peces tance away to eat the fish, tear it apart, or just throw colectados por pescadores a bordo de embarca- it around on the surface of the water. -

Frontmatter Final.Qxd

5-14 Committee Rept final:5-9 Committee Rept 11/8/08 6:11 PM Page 5 COMMITTEE REPORT CalCOFI Rep., Vol. 49, 2008 Part I REPORTS, REVIEW, AND PUBLICATIONS REPORT OF THE CALCOFI COMMITTEE NOAA HIGHLIGHTS The David Starr Jordan will conduct operations in the Southern California Bight in San Diego and stations CalCOFI Cruises from Point Conception north to San Francisco, Cali- The CalCOFI program completed its fifty-eighth year fornia. The Miller Freeman will synoptically conduct sim - with four successful quarterly cruises. All four cruises ilar operations over the northern section of the CCE, were manned by personnel from both the NOAA in Port Townsend, Washington, and south to San Fran- Fisheries Southwest Fisheries Science Center (SWFSC) cisco. An additional California Current Ecosystem sur - and Scripps Institution of Oceanography (SIO). The fall vey will be conducted in July 2008. 2007 cruise was conducted on the SIO RV New Horizon and covered the southern lines of the CalCOFI pattern. CalCOFI Ichthyoplankton Update The winter and spring 2007 cruises were conducted on The SWFSC Ichthyoplankton Ecology group made the NOAA RV David Starr Jordan . The Jordan covered progress on a multi-year project to update larval fish lines 93 to line 60 just north of San Francisco. The sum - identifications to current standards from 1951 to the pre - mer 2007 cruise was on the SIO RV New Horizon , and sent, which will ultimately provide taxonomic consis - covered the standard CalCOFI pattern. tency throughout the CalCOFI ichthyoplankton time Standard CalCOFI protocols were followed during series. The group updated samples collected during the the four quarterly cruises. -

Yellowfin Tuna

Ahi yellown tuna (Thunnus albacares) is one of two Islands. species known in Hawaii simply as Fishing Methods: intermediaries on all islands, or di- ahi. Similar in general appearance rectly to wholesalers and retailers, or it may be shared with family and to bigeye tuna (the other species - known as ahi friends. Most ahi is sold fresh, but men. A large part of the commercial surpluses caught during the peak be recognized by its more torpedo catch (44%) is harvested by longline shaped body, smaller head and eyes. summer season are sometimes dried boats, which may search for tuna and smoked. In Hawaii, shibi is another name up to 800 nautical miles from port and set hooks in deep waters. Yel- Quality to depths below 600 ft. Landings by either bigeye or albacore tuna. Al- lengthen with age. the island of Hawaii, can be sub- stantial (36%) in some years. Troll- Seasonality & How ers contribute most of the remain- does not retain the beautiful natu- They Are Caught der (20%) of the commercial catch ral red color as long as bigeye. The - Availability and Seasonality: - Caught year-round in Hawaii’s wa- ing tournaments held in Hawaii. method, care in handling and other Distribution: abundant during the summer sea- The longline catch and some of the son (May-September). There are handline (ika-shibi) catch of ahi is species. Noticeable changes occur auction. The majority of the hand- Hawaii. ocean surface temperatures and line catch is sold to wholesalers and other oceanographic conditions fa- intermediary buyers on the island of surface during the summer season vor the migration of ahi schools to are susceptible to a quality defect The troll catch may be marketed known as “burnt tuna”. -

Albacore Tuna Have fl Uctuated Considerably from Year To

Tuna [211] 86587_p211_220.indd 211 12/30/04 4:53:37 PM highlights ■ The catches of Pacifi c bluefi n tuna and North Pacifi c albacore tuna have fl uctuated considerably from year to Ocean year, but no upward or downward trends are apparent for either species. and ■ Increasing the age at entry of Pacifi c bluefi n into the fi shery might increase the yields per recruit of that Climate species. ■ The status of North Pacifi c albacore is uncertain, but most scientists believe that greater harvests of that species Changes would not be sustainable. [212] 86587_p211_220.indd 212 12/30/04 4:53:38 PM background The Inter-American Tropical Tuna Commission (IATTC) studies the tunas of the eastern Pacifi c Ocean (EPO), defi ned for its purposes as the area bounded by the coastline of North, Central, and South America, 40ºN, 150ºW, and 40ºS. The IATTC staff maintains records for most of the vessels that fi sh at the surface for skipjack tuna (Katsuwonus pelamis), yellowfi n tuna (Thunnus albacares), bigeye tuna (T. obesus), and Pacifi c bluefi n tuna (T. orientalis) in the EPO. Pacifi c bluefi n and albacore tuna (T. alalunga) are the tunas most relevant to the region of interest to PICES. Pacifi c bluefi n tuna Spawning of Pacifi c bluefi n apparently takes place only Age-1 and older fi sh are caught by purse seining, in the western Pacifi c Ocean (WPO). Some juvenile mostly during May-September between about 30°- bluefi n move from the WPO to the EPO, and then later 42°N and 140°-152°E. -

Seafood Guide

eat It’s good for you! What pregnant and breastfeeding women and parents of young children need to know. Fish are nutritious and most are very How can you safely safe to eat. eat fish? • Fish have protein and healthy fats, called omega-3s, which are not • Eat a variety of fish that are lower found in other meats. in mercury. • Omega-3s are good for your heart • Eat the amounts of fish shown on and brain. the other side of this pamphlet. • The nutrients in fish are especially • Eat only the flesh or meat of important as your baby develops the fish. Throw away the bones, during pregnancy, throughout head, guts, fat, and skin. breastfeeding, and as your young • Avoid shark, swordfish, tilefish, or child grows. king mackerel. They are highest in • Some fish may contain a chemical mercury. called mercury. Too much mercury • Avoid raw and undercooked in your diet can be harmful. It’s fish and shellfish. best to eat fish that are lower in mercury. For more information about mercury in your fish, visit the Environmental Protection Agency — Fish Advisory at www.epa.gov/choose-fish-and-shellfish-wisely. choose safe Follow these tips to enjoy the health benefits of eating fish low in mercury and high in omega-3s. 1. Safe to Eat 2. Do Not Eat Eat fish from the list below 2 to 3 These fish are high in mercury. times a week. Choose fish from stores • Shark • King Mackerel or restaurants. • Swordfish • Tilefish • For women, eat about 8 to 12 ounces a week total. -

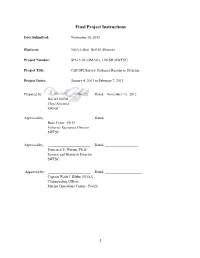

Final Project Instructions

Final Project Instructions Date Submitted: November 16, 2012 Platform: NOAA Ship Bell M. Shimada Project Number: SH-13-01 (OMAO), 1301SH (SWFSC) Project Title: CalCOFI Survey, Fisheries Resources Division. Project Dates: January 4, 2013 to February 7, 2013 Prepared by: ________________________ Dated: _November 16,_2012_ David Griffith Chief Scientist SWFSC Approved by: ________________________ Dated: __________________ Russ Vetter , Ph.D. Fisheries Resources Director SWFSC Approved by: ________________________ Dated: __________________ Francisco E. Werner, Ph.D. Science and Research Director SWFSC Approved by: ________________________ Dated: ________________ Captain Wade J. Blake, NOAA Commanding Officer Marine Operations Center - Pacific 1 I. Overview A. Brief Summary and Project Period Survey the distributions and abundances of pelagic fish stocks, their prey, and their biotic and abiotic environments in the area of the California Current between San Francisco, California and San Diego, California during the period of January 9 to February 2, 2013. B. Service Level Agreements Of the 33 DAS scheduled for this project, 0 DAS are funded by the program and 33 DAS are funded by OMAO. This project is estimated to exhibit a medium Operational Tempo. C. Operating Area 2 D. Summary of Objectives Survey the distributions and abundances of pelagic fish stocks, their prey, and their biotic and abiotic environments in the area of the California Current between San Francisco, California and San Diego, California. The following are specific objectives for the Winter CalCOFI. I.D.1. Continuously sample pelagic fish eggs using the Continuous Underway Fish Egg Sampler (CUFES). The data will be used to estimate the distributions and abundances of spawning hake, anchovy, mackerel, and early spawning Pacific sardine. -

Views Concerning Use of the Living Resources of the California Current

Calif. JIw. Res. Comna., CalCOFI Rept., 13 : 91-94, 1969 VIEWS CONCERNING USE OF THE LIVING RESOURCES OF THE CALIFORNIA CURRENT GERALD V. HOWARD, Regional Director Pacific Southwest Region Bureau of Commercial Fisheries Terminal Island, California I have been asked to express the views of the Bu- ‘wetfish ’ ’ fisheries which harvest mackerels, anchovies reau of Commercial Fisheries concerning the legal, and bonito ; and the “ bottomfish ” fisheries which har- economic, sociological and technological problems im- rest, though not exclusiuely, species taken by trawl- peding the best use of the living resources of the ing. California Current and how they can be resolved. Californians generally do not think of the tropical The impediments are generally rather well knowii. It tunas as a resource of the California Current, prob- is their resolution which presents the challenge. ably because they occur in its southern extension off A rnajor objective of the programs of the Bureau Baja California and rarely in commercial quantities of Commercial Fisheries is to seek the resolution of off southern California. I have included them not only problems which handicap the economic well-being of because they support California’s most important the domestic fishing industry and hinder the best use fishery, but because the long-range tuna fleet’s experi- of the fishery resources. Success of Bureau research ence in overcoming economic difficulties has been more and service programs, however, depends on close col- successful than that of other elements of the Cali- laboration and cooperation with other parties, espe- fornia fishing fleet. I especially wish to mention cially State agencics. -

C1. Tuna and Tuna-Like Species

163 C1. TUNA AND TUNA-LIKE SPECIES exceptional quality reached US$500 per kg and by Jacek Majkowski * more recently even more, but such prices referring to very few single fish do not reflect the INTRODUCTION situation with the market. Bigeye are also well priced on the sashimi markets. Although The sub-order Scombroidei is usually referred to yellowfin are also very popular on these markets, as tuna and tuna-like species (Klawe, 1977; the prices they bring are much lower. For Collette and Nauen, 1983; Nakamura, 1985). It is canning, albacore fetch the best prices due to composed of tunas (sometimes referred to as true their white meat, followed by yellowfin and tunas), billfishes and other tuna-like species. skipjack for which fishermen are paid much less They include some of the largest and fastest than US$1 per kg. The relatively low prices of fishes in the sea. canning-quality fish are compensated by their The tunas (Thunnini) include the most very large catches, especially in the case of economically important species referred to as skipjack and yellowfin. Longtail tuna principal market tunas because of their global (T. tonggol) is becoming increasingly important economic importance and their intensive for canning and the subject of substantial international trade for canning and sashimi (raw international trade. The consumption of tuna and fish regarded as delicacy in Japan and tuna-like species in forms other than canned increasingly, in several other countries). In fact, products and sashimi is increasing. the anatomy of some tuna species seems to have The tunas other than the principal market species been purpose-designed for canning and loining. -

A Historical Review of Fisheries Statistics and Environmental and Societal Influences Off the Palos Verdes Peninsula, California

STULL ET AL. : PALOS VERDES SPORT AND COMMERCIAL FISHERY CalCOFI Rep., Vol. XXVIII, 1987 A HISTORICAL REVIEW OF FISHERIES STATISTICS AND ENVIRONMENTAL AND SOCIETAL INFLUENCES OFF THE PALOS VERDES PENINSULA, CALIFORNIA JANET K. STULL, KELLY A. DRYDEN PAUL A. GREGORY Los Angeles County Sanitation Districts California Department of Fish and Game P.O. Box 4998 245 West Broadway Whittier. California 90607 Long Beach, California 90802 ABSTRACT peracion ambiental significativa y puede estar aso- A synopsis of partyboat and commercial fish and ciado con una reducci6n en la contaminacion del invertebrate catches is presented for the Palos medio ambiente marino costero. Verdes region. Fifty years (1936-85) of partyboat catch, in numbers of fish and angler effort, and 15 INTRODUCTION years (1969-83) of commercial landings, in Our goals were to summarize long-term fish and pounds, are reviewed. Several hypotheses are invertebrate catch statistics gathered by the Cali- proposed to explain fluctuations in partyboat fornia Department of Fish and Game (CDFG) for (commercial passenger fishing vessel) and com- the Palos Verdes Peninsula, to infer relative fish mercial fishery catches. Where possible, compari- abundance and human consumption rates, and, sons are drawn to relate catch information to envi- where possible, to better understand influences ronmental and societal influences. This report from natural and human environmental perturba- documents trends in historical resource use and tions. We examined total catches and common and fish consumption patterns, and is useful for re- economically important species, in addition to spe- gional fisheries management. The status of several cies with reported elevated body burdens of con- species has improved since the early to mid-1970s. -

Physical Forcing on Fish Abundance in the Southern California Current System

Received: 19 May 2016 | Accepted: 8 December 2017 DOI: 10.1111/fog.12267 ORIGINAL ARTICLE Physical forcing on fish abundance in the southern California Current System Lia Siegelman-Charbit1 | J. Anthony Koslow2 | Michael G. Jacox3,4 | Elliott L. Hazen3 | Steven J. Bograd3 | Eric F. Miller5 1Universite Pierre et Marie Curie, Paris, France Abstract 2Scripps Institution of Oceanography, The California Current System (CCS) is an eastern boundary current system with University of California, San Diego, La Jolla, strong biological productivity largely due to seasonal wind-driven upwelling and CA, USA 3National Oceanic and Atmospheric transport of the California Current (CC). Two independent, yet complementary time Administration, Monterey, CA, USA series, CalCOFI ichthyoplankton surveys and sampling of southern California power 4 Institute of Marine Sciences, University of plant cooling-water intakes, have indicated that an assemblage of predominantly California, Santa Cruz, CA, USA 5MBC applied Environmental Sciences, cool-water affinity fishes spanning nearshore to oceanic environments in the south- Costa Mesa, CA, USA ern CCS has declined dramatically from the 1970s to the 2000s. We examined Correspondence potential oceanographic drivers behind this decline both within and north of the L. Siegelman-Charbit CalCOFI survey area in order to capture upstream processes as well. Empirical Email: [email protected] orthogonal function (EOF) analyses using output from a data-assimilative regional ocean model revealed significant relationships -

Intrinsic Vulnerability in the Global Fish Catch

The following appendix accompanies the article Intrinsic vulnerability in the global fish catch William W. L. Cheung1,*, Reg Watson1, Telmo Morato1,2, Tony J. Pitcher1, Daniel Pauly1 1Fisheries Centre, The University of British Columbia, Aquatic Ecosystems Research Laboratory (AERL), 2202 Main Mall, Vancouver, British Columbia V6T 1Z4, Canada 2Departamento de Oceanografia e Pescas, Universidade dos Açores, 9901-862 Horta, Portugal *Email: [email protected] Marine Ecology Progress Series 333:1–12 (2007) Appendix 1. Intrinsic vulnerability index of fish taxa represented in the global catch, based on the Sea Around Us database (www.seaaroundus.org) Taxonomic Intrinsic level Taxon Common name vulnerability Family Pristidae Sawfishes 88 Squatinidae Angel sharks 80 Anarhichadidae Wolffishes 78 Carcharhinidae Requiem sharks 77 Sphyrnidae Hammerhead, bonnethead, scoophead shark 77 Macrouridae Grenadiers or rattails 75 Rajidae Skates 72 Alepocephalidae Slickheads 71 Lophiidae Goosefishes 70 Torpedinidae Electric rays 68 Belonidae Needlefishes 67 Emmelichthyidae Rovers 66 Nototheniidae Cod icefishes 65 Ophidiidae Cusk-eels 65 Trachichthyidae Slimeheads 64 Channichthyidae Crocodile icefishes 63 Myliobatidae Eagle and manta rays 63 Squalidae Dogfish sharks 62 Congridae Conger and garden eels 60 Serranidae Sea basses: groupers and fairy basslets 60 Exocoetidae Flyingfishes 59 Malacanthidae Tilefishes 58 Scorpaenidae Scorpionfishes or rockfishes 58 Polynemidae Threadfins 56 Triakidae Houndsharks 56 Istiophoridae Billfishes 55 Petromyzontidae