Ferdinand Buisson

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Nobel Peace Prize

TITLE: Learning From Peace Makers OVERVIEW: Students examine The Dalai Lama as a Nobel Laureate and compare / contrast his contributions to the world with the contributions of other Nobel Laureates. SUBJECT AREA / GRADE LEVEL: Civics and Government 7 / 12 STATE CONTENT STANDARDS / BENCHMARKS: -Identify, research, and clarify an event, issue, problem or phenomenon of significance to society. -Gather, use, and evaluate researched information to support analysis and conclusions. OBJECTIVES: The student will demonstrate the ability to... -know and understand The Dalai Lama as an advocate for peace. -research and report the contributions of others who are recognized as advocates for peace, such as those attending the Peace Conference in Portland: Aldolfo Perez Esquivel, Robert Musil, William Schulz, Betty Williams, and Helen Caldicott. -compare and contrast the contributions of several Nobel Laureates with The Dalai Lama. MATERIALS: -Copies of biographical statements of The Dalai Lama. -List of Nobel Peace Prize winners. -Copy of The Dalai Lama's acceptance speech for the Nobel Peace Prize. -Bulletin board for display. PRESENTATION STEPS: 1) Students read one of the brief biographies of The Dalai Lama, including his Five Point Plan for Peace in Tibet, and his acceptance speech for receiving the Nobel Prize for Peace. 2) Follow with a class discussion regarding the biography and / or the text of the acceptance speech. 3) Distribute and examine the list of Nobel Peace Prize winners. 4) Individually, or in cooperative groups, select one of the Nobel Laureates (give special consideration to those coming to the Portland Peace Conference). Research and prepare to report to the class who the person was and why he / she / they won the Nobel Prize. -

Liste Der Nobelpreisträger

Physiologie Wirtschafts- Jahr Physik Chemie oder Literatur Frieden wissenschaften Medizin Wilhelm Henry Dunant Jacobus H. Emil von Sully 1901 Conrad — van ’t Hoff Behring Prudhomme Röntgen Frédéric Passy Hendrik Antoon Theodor Élie Ducommun 1902 Emil Fischer Ronald Ross — Lorentz Mommsen Pieter Zeeman Albert Gobat Henri Becquerel Svante Niels Ryberg Bjørnstjerne 1903 William Randal Cremer — Pierre Curie Arrhenius Finsen Bjørnson Marie Curie Frédéric John William William Mistral 1904 Iwan Pawlow Institut de Droit international — Strutt Ramsay José Echegaray Adolf von Henryk 1905 Philipp Lenard Robert Koch Bertha von Suttner — Baeyer Sienkiewicz Camillo Golgi Joseph John Giosuè 1906 Henri Moissan Theodore Roosevelt — Thomson Santiago Carducci Ramón y Cajal Albert A. Alphonse Rudyard \Ernesto Teodoro Moneta 1907 Eduard Buchner — Michelson Laveran Kipling Louis Renault Ilja Gabriel Ernest Rudolf Klas Pontus Arnoldson 1908 Metschnikow — Lippmann Rutherford Eucken Paul Ehrlich Fredrik Bajer Theodor Auguste Beernaert Guglielmo Wilhelm Kocher Selma 1909 — Marconi Ostwald Ferdinand Lagerlöf Paul Henri d’Estournelles de Braun Constant Johannes Albrecht Ständiges Internationales 1910 Diderik van Otto Wallach Paul Heyse — Kossel Friedensbüro der Waals Allvar Maurice Tobias Asser 1911 Wilhelm Wien Marie Curie — Gullstrand Maeterlinck Alfred Fried Victor Grignard Gerhart 1912 Gustaf Dalén Alexis Carrel Elihu Root — Paul Sabatier Hauptmann Heike Charles Rabindranath 1913 Kamerlingh Alfred Werner Henri La Fontaine — Robert Richet Tagore Onnes Theodore -

H-France Review Vol. 20 (June 2020), No. 95 Anne-Claire Husser, Ferdinand Buisson, Pense

H-France Review Volume 20 (2020) Page 1 H-France Review Vol. 20 (June 2020), No. 95 Anne-Claire Husser, Ferdinand Buisson, penseur de l’autorité: Du théologique au pédagogique. Paris: Honoré Champion, 2019. 446 pp. Notes, bibliography, index. €58.00 (pb). ISBN 9782745350657. Review by Helena Rosenblatt, CUNY Graduate Center. There used to be a consensus among scholars that France lacked a liberal tradition. What France was best known for was its illiberal culture, traceable at least as far back as Jean-Jacques Rousseau and his “proto-totalitarian” disciples, the revolutionary Jacobins. Under the sway of the Jacobin legacy, or so it was said, nineteenth-century French thinkers, with only rare exceptions, concerned themselves not so much with reducing the power of the state as with appropriating it for their own purposes. And, contrary to their Anglo-American counterparts, French “liberals,” had little regard for the individual. In a sense, then, French liberalism wasn’t actually liberal at all. And it was supposedly the illiberalism of French political culture that was to blame for the country’s nineteenth-century difficulties in establishing a stable, liberal regime. Unlike Britain, whose liberal traditions helped it to evolve peacefully, France’s political evolution was one of successive revolutions. The story of French liberalism was one of failure. Recent scholarship has exposed the ahistoricism and Anglo-American prejudice of this point of view. Since the early 1980s, a plethora of new studies has unearthed a rich and robust French liberal tradition including theorists from Benjamin Constant and Madame de Staël in the early nineteenth century to Raymond Aron and Marcel Gauchet in the twentieth. -

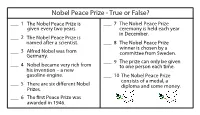

Nobel Peace Prize - True Or False?

Nobel Peace Prize - True or False? ___ 1 T he Nobel Peace Prize is ___ 7 The Nobel Peace Prize given every two years. ceremony is held each year in December. ___ 2 T he Nobel Peace Prize is n amed after a scientist. ___ 8 The Nobel Peace Prize winner is chosen by a ___ 3 A lfred Nobel was from c ommittee from Sweden. G ermany. ___ 9 T he prize can only be given ___ 4 N obel became very rich from t o one person each time. his invention – a new gasoline engine. ___ 10 T he Nobel Peace Prize consists of a medal, a ___ 5 There are six dierent Nobel diploma and some money. Prizes. ___ 6 The rst Peace Prize was awarded in 1946 . Nobel Peace Prize - True or False? ___F 1 T he Nobel Peace Prize is ___T 7 The Nobel Peace Prize given every two years. Every year ceremony is held each year in December. ___T 2 T he Nobel Peace Prize is n amed after a scientist. ___F 8 The Nobel Peace Prize winner is chosen by a Norway ___F 3 A lfred Nobel was from c ommittee from Sweden. G ermany. Sweden ___F 9 T he prize can only be given ___F 4 N obel became very rich from t o one person each time. Two or his invention – a new more gasoline engine. He got rich from ___T 10 T he Nobel Peace Prize dynamite T consists of a medal, a ___ 5 There are six dierent Nobel diploma and some money. -

Accepted Version

Article The spatiality of geography teaching and cultures of alternative education: the 'intuitive geographies' of the anarchist school in Cempuis (1880-1894) FERRETTI, Federico Abstract As part of current studies focusing on geographies of education and spatiality of teaching and learning, this article addresses the didactic experiences of historical anarchist schools, which opened in several countries at the end of the 19th century. The article deals especially with the example of the Cempuis School (1880–1894) in France, which was run by the anarchist activist and teacher Paul Robin. The aim here is twofold. First, the article clarifies the function of space and spatiality in the teaching and learning practices of the anarchist schools, at least according to the available sources; second, it reconstructs the international cultural transfer, still little known, of the geographical knowledge produced by scholars like Reclus and Kropotkin in the field of educational practices. Finally, the article hopes to contribute to the understanding of spatial educational practices in current alternative, democratic and radical schools. Reference FERRETTI, Federico. The spatiality of geography teaching and cultures of alternative education: the 'intuitive geographies' of the anarchist school in Cempuis (1880-1894). Cultural Geographies, 2016, vol. 23, no. 4, p. 615-633 DOI : 10.1177/1474474015612731 Available at: http://archive-ouverte.unige.ch/unige:88326 Disclaimer: layout of this document may differ from the published version. 1 / 1 The spatiality of geography teaching and cultures of alternative education: the ‘intuitive geographies’ of the anarchist school in Cempuis (1880-1894) Federico Ferretti [email protected] Introduction: spaces of alternative education This paper addresses the spaces of teaching and learning within the experiences of the schools that took part in the anarchist education movement, often called ‘Modern schools’ or ‘Ferrer Schools’, which opened in the late 19 th century in several countries of Europe, 1 North America,2 and Latin America. -

List of Nobel Laureates 1

List of Nobel laureates 1 List of Nobel laureates The Nobel Prizes (Swedish: Nobelpriset, Norwegian: Nobelprisen) are awarded annually by the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences, the Swedish Academy, the Karolinska Institute, and the Norwegian Nobel Committee to individuals and organizations who make outstanding contributions in the fields of chemistry, physics, literature, peace, and physiology or medicine.[1] They were established by the 1895 will of Alfred Nobel, which dictates that the awards should be administered by the Nobel Foundation. Another prize, the Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences, was established in 1968 by the Sveriges Riksbank, the central bank of Sweden, for contributors to the field of economics.[2] Each prize is awarded by a separate committee; the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences awards the Prizes in Physics, Chemistry, and Economics, the Karolinska Institute awards the Prize in Physiology or Medicine, and the Norwegian Nobel Committee awards the Prize in Peace.[3] Each recipient receives a medal, a diploma and a monetary award that has varied throughout the years.[2] In 1901, the recipients of the first Nobel Prizes were given 150,782 SEK, which is equal to 7,731,004 SEK in December 2007. In 2008, the winners were awarded a prize amount of 10,000,000 SEK.[4] The awards are presented in Stockholm in an annual ceremony on December 10, the anniversary of Nobel's death.[5] As of 2011, 826 individuals and 20 organizations have been awarded a Nobel Prize, including 69 winners of the Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences.[6] Four Nobel laureates were not permitted by their governments to accept the Nobel Prize. -

Verzeichnis Der Nobelpreisträger List of Nobel Prize Winners

Verzeichnis der Nobelpreisträger List of Nobel Prize Winners Nobel Prize Winners 281 Nobelpreis für Physik/Nobel 1936 Peter Debye (Deutschland/Ger.)2 1969 Max Ludwig Delbrück (USA)2 Prize for physics 1943 Georg Karl von Hevesy mit/with Alfred Day Hershey (USA) (Schweden/Sweden)2 und/and Salvador Edward Luria 1921 Albert Einstein (Deutschland/Ger.)2 1962 Max Ferdinand Perutz (USA) 1925 James Franck (Deutschland/Ger.)-' ! 1970 Sir Bernard Kau mit/with Gustav Hertz (Großbritannien/U. K.) (Großbritannien/U. K.)2 (Deutschland/Ger.) mit/with John Cowdery Kendrew mit/with Julius Axelrod (USA) 1933 Erwin Schrödinger (Großbritannien/U. K.) 2 2 und/and Ulf Svante Euler-Chelpin (Österreich/Aus.) 1971 Gerhard Hemberg (Kanada/Can.) (Schweden/Swedcn) mit/with Paul Dirac (Großbritannien/U.K.) 1936 Victor Hess (Österreich/Aus.)2 mit/with Carl David Anderson (USA) Nobelpreis für Physiologie uod Nobelpreis für Literatur/Nobel 1943 Otto Stern (USA)2 2 Medizin/Nobel Prize for 1952 Felix Bloch (USA) Prize for literature physiology and medicine 1929 Thomas Mann (Deutschland/Ger.)2 mit/with Edward Mills Purcell 1922 Otto Fritz Meyerhof 1966 Nelly Sachs (Schweden/Sweden)2 (USA) (Deutschland/Ger.)2 mit/with Shmuel Josef Agnon 1954 Max Born (Bundesrepublik mit/with Archibald Vivian Hill (Israel) Deutschland/Fed. Rep. Ger.)2 (Großbritannien/U. K.) 1981 Elias Canetti mit/with Walter Bothe 1936 Otto Loewi (Österreich/Aus.)2 (Großbritannien/U. K.)2 (Bundesrepublik Deutschland/Fed. mit/with Sir Henry Halle» Dale Rep. Ger.) (Großbritannien/U. K.) 1967 Hans Albrecht Bethe (USA)2 1945 Sir Ernst Boris Chain 1971 Dennis Gabor (Großbritannien/U. K.)2 2 (GroBbritannien/U. -

Nobel Prizes List from 1901

Nature and Science, 4(3), 2006, Ma, Nobel Prizes Nobel Prizes from 1901 Ma Hongbao East Lansing, Michigan, USA, Email: [email protected] The Nobel Prizes were set up by the final will of Alfred Nobel, a Swedish chemist, industrialist, and the inventor of dynamite on November 27, 1895 at the Swedish-Norwegian Club in Paris, which are awarding to people and organizations who have done outstanding research, invented groundbreaking techniques or equipment, or made outstanding contributions to society. The Nobel Prizes are generally awarded annually in the categories as following: 1. Chemistry, decided by the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences 2. Economics, decided by the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences 3. Literature, decided by the Swedish Academy 4. Peace, decided by the Norwegian Nobel Committee, appointed by the Norwegian Parliament, Stortinget 5. Physics, decided by the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences 6. Physiology or Medicine, decided by Karolinska Institutet Nobel Prizes are widely regarded as the highest prize in the world today. As of November 2005, a total of 776 Nobel Prizes have been awarded, 758 to individuals and 18 to organizations. [Nature and Science. 2006;4(3):86- 94]. I. List of All Nobel Prize Winners (1901 – 2005): 31. Physics, Philipp Lenard 32. 1906 - Chemistry, Henri Moissan 1. 1901 - Chemistry, Jacobus H. van 't Hoff 33. Literature, Giosuè Carducci 2. Literature, Sully Prudhomme 34. Medicine, Camillo Golgi 3. Medicine, Emil von Behring 35. Medicine, Santiago Ramón y Cajal 4. Peace, Henry Dunant 36. Peace, Theodore Roosevelt 5. Peace, Frédéric Passy 37. Physics, J.J. Thomson 6. Physics, Wilhelm Conrad Röntgen 38. -

Download Download

Nordic Journal of Comparative and International Education (NJCIE) NJCIE 2017, Vol. 1(2), 29–46 http://doi.org/10.7577/njcie.2600 World-Class or World-Ranked Universities? Performativity and Nobel Laureates in Peace and Literature Brian D. Denman1 Senior Lecturer, University of New England, Australia Copyright the author Peer-reviewed article; received 12 January 2018; accepted 24 February 2018 Abstract It is erroneous to draw too many conclusions about global university rankings. Making a university’s rep- utation rest on the subjective judgement of senior academics and over-reliance on interpreting and utilising secondary data from bibliometrics and peer assessments have created an enmeshed culture of performativity and over-emphasis on productivity. This trend has exacerbated unhealthy competition and mistrust within the academic community and also discord outside its walls. Surely if universities are to provide service and thrive with the advancement of knowledge as a primary objective, it is important to address the methods, concepts, and representation necessary to move from an emphasis on quality assurance to an emphasis on quality enhancement. This overview offers an analysis of the practice of international ranking. US News and World Report Best Global Universities Rankings, the Times Supplement World University Rankings, and the Shanghai Jiao Tong University Academic Ranking of World Universities are analysed. While the presence of Nobel lau- reates in the hard sciences has been seized upon for a number of years as quantifiable evidence of producing world-class university education, Nobel laureates in peace and literature have been absent from such rank- ings. Moreover, rankings have been based on employment rather than university affiliation. -

Galardonados Con El Premio Nobel De La Paz

Galardonados con el Premio Nobel de la Paz (información obtenida en Wikipedia) 1901 -1909 1901 Jean Henri Dunant ( Suiza ), Frédéric Passy ( Francia ) 1902 Élie Ducommun ( Suiza ), Charles Albert Gobat ( Suiza ) 1903 William Randal Cremer ( Inglaterra ) 1904 Instituto de Derecho Internac ional , organización privada destinada al estudio y desarrollo del Derecho internacional . 1905 Bertha von Suttner ( Austria ) 1906 Theodore Roosevelt ( Estados Unidos ), presidente de éste país 1907 Ernesto Teodoro Mo neta ( Italia ), Louis Renault ( Francia ) 1908 Klas Pontus Arnoldson ( Suecia ), Fredrik Bajer ( Dinamarca ) 1909 Auguste Marie François Beernaert ( Bélgica ), Paul Henri Benjamin Balluet d'Estournelles ( Francia ), barón de Constant de Rébecque 1910 -1919 1910 Oficina Internacional por la Paz (En francés:Bureau international permanent de la Paix, en inglés: Permanent International Peace Bureau) 1911 Tobias Michael Carel Asser ( Países Bajos ), Alfred Hermann Fried ( Austria ) 1912 Elihu Root ( Estados Unidos ) 1913 Henri La Fontaine ( Bélgica ) 1ª GUERRA MUNDIAL 1914 Destinado al Fondo Especial de esta secció n del premio 1915 Destinado al Fondo Especial de esta sección del premio 1916 Destinado al Fondo Especial de esta sección del premio 1917 Comité Internacional de la Cruz Roja ( CIRC ) 1918 Destinado al Fondo Especial de esta sección del premio 1919 Thomas Woodrow Wilson ( Estados Unidos ), presidente de este país 1920 -1929 1920 Léon Victor Auguste Bourgeois ( Francia ) 1921 Karl Hjalmar Branting ( Suecia ), Christian Lous Lange -

Educational Pressure Groups and the Indoctrination of the Radical Ideology of Solidarism, 1895-1914

/. E. S. HAYWARD EDUCATIONAL PRESSURE GROUPS AND THE INDOCTRINATION OF THE RADICAL IDEOLOGY OF SOLIDARISM, 1895-1914 On a previous occasion, I have argued that during the two decades preceding the First World War, the French Radical Party, under electoral pressure from the separate and then united Socialist parties of Jaures and Guesde, began to look for a doctrine around which they could rally to defend their recently acquired hold on power against both the individualists to their right and the coUectivists on their left.1 It was the six-month duration of Leon Bourgeois' purely Radical government of 1895-6 and his Lettres sur le Mouvement Social of 1895, republished in 1896 as a book and entitled Solidarity that marked the beginning of the belle e'poque of Radical-socialism and of the Third Republic. It was argued that during the next two decades, Bourgeois' doctrine of Solidarism became for platform, and to a lesser extent, practical political purposes, the official social philosophy of the regime, probably reaching its apotheosis at the time of the Paris World Exhibition of 1900. This pre-eminent position in the doctrinal firmament of France was not achieved without an intensive campaign through a variety of mainly educational pressure groups - to be anticipated in a lay "Republique des professeurs." It is the principal channels and people through which this indoctrination was propagated that will be our concern in the pages that follow. However, the activities of the "Universites Populaires", which were closely allied to the movements discussed here, have been passed over because they have formed the subject-matter of a separate study.2 MACE AND THE MASONIC BACKGROUND No discussion of the origins of the social legislation of the Third Republic and the place of the idea of solidarity in French social 1 See my article "The official Social Philosophy of the French Third Republic: Leon Bourgeois and Solidarism", in: The International Review of Social History, 1961, VI, Part i, pp. -

Nobel Peace Prize Laureates As International Norm Entrepreneurs Roger P

Notre Dame Law School NDLScholarship Journal Articles Publications 2008 The obN el Effect: Nobel Peace Prize Laureates as International Norm Entrepreneurs Roger P. Alford Notre Dame Law School, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.nd.edu/law_faculty_scholarship Part of the Human Rights Law Commons, Intellectual History Commons, International Law Commons, Political History Commons, and the Social History Commons Recommended Citation Roger P. Alford, The Nobel Effect: Nobel Peace Prize Laureates as International Norm Entrepreneurs, 49 Va. J. Int'l L. 61 (2008-2009). Available at: https://scholarship.law.nd.edu/law_faculty_scholarship/406 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Publications at NDLScholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal Articles by an authorized administrator of NDLScholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Nobel Effect: Nobel Peace Prize Laureates as International Norm Entrepreneurs ROGER P. ALFORD* Introduction ....................................................................................... 62 I. The Pacifist Period (1901-1913) ............................................. 67 A. The Populist Pacifists ................................................... 68 B. The Parliamentary Pacifists ........................................... 72 C. The International Jurists ............................................... 74 D. Norm Evolution in the Pacifist Period .......................... 76 II. The Statesman Period (1917-1938)