Working Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Article Fairy Marriages in Tolkien’S Works GIOVANNI C

article Fairy marriages in Tolkien’s works GIOVANNI C. COSTABILE Both in its Celtic and non-Celtic declinations, the motif the daughter of the King of Faerie, who bestows on him a of the fairy mistress has an ancient tradition stretching magical source of wealth, and will visit him whenever he throughout different areas, ages, genres, media and cul- wants, so long as he never tells anybody about her.5 Going tures. Tolkien was always fascinated by the motif, and used further back, the nymph Calypso, who keeps Odysseus on it throughout his works, conceiving the romances of Beren her island Ogygia on an attempt to make him her immortal and Lúthien, and Aragorn and Arwen. In this article I wish husband,6 can be taken as a further (and older) version of to point out some minor expressions of the same motif in the same motif. Tolkien’s major works, as well as to reflect on some over- But more pertinent is the idea of someone’s ancestor being looked aspects in the stories of those couples, in the light of considered as having married a fairy. Here we can turn to the often neglected influence of Celtic and romance cultures the legend of Sir Gawain, as Jessie Weston and John R. Hul- on Tolkien. The reader should also be aware that I am going bert interpret Gawain’s story in Sir Gawain and the Green to reference much outdated scholarship, that being my pre- Knight as a late, Christianised version of what once was a cise intent, though, at least since this sort of background fairy-mistress tale in which the hero had to prove his worth may conveniently help us in better understanding Tolkien’s through the undertaking of the Beheading Test in order to reading of both his theoretical and actual sources. -

Irish Children's Literature and the Poetics of Memory, 1892-2016

Irish Children’s Literature and the Poetics of Memory, 1892-2016 A Thesis submitted to the School of English at the University of Dublin, Trinity College, for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy. February 2019 Rebecca Ann Long I declare that this thesis has not been submitted as an exercise for a degree at this or any other university and it is entirely my own work. I agree to deposit this thesis in the University’s open access institutional repository or allow the Library to do so on my behalf, subject to Irish Copyright Legislation and Trinity College Library conditions of use and acknowledgement. _________________________________ Rebecca Long February 2019 TABLE OF CONTENTS SUMMARY………………………………………………………………………………..i ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS……………………………………………………………....iii INTRODUCTION………………………………………………………………………....4 CHAPTER ONE: RETRIEVING……………………………………………………………………………29 CHAPTER TWO: RE- TELLING……………………………………………………………………………...…64 CHAPTER THREE: REMEMBERING……………………………………………………………………....106 CHAPTER FOUR: RE- IMAGINING………………………………………………………………………........158 CONCLUSION…………………………………………………………………..……..210 WORKS CITED………………………….…………………………………………………….....226 Summary This thesis explores the recurring patterns of Irish mythological narratives that influence literature produced for children in Ireland following the Celtic Revival and into the twenty- first century. A selection of children’s books published between 1892 and 2016 are discussed with the aim of demonstrating the development of a pattern of retrieving, re-telling, remembering and re-imagining myths -

The Corran Herald Issue 26, 1994

THE s9 CORRAN HERALDI. A Ballymote Heritage Group Production. Issue No. 26 Summer 1994 Price £1.00 Hills may be green far JIM McGARRY away but the rich vari- ety of the hills of Coun- Yes! ty Sligo hold captive the mind and eye of anyone but give ME Sligo reared in that County. From the Curliew Hills in the south to Ben Bulben in the North "The world-wide air was azure every hillock is linked by a gossamer thread of myth, folklore and history. And all the brooks ran gold" Keshcorran, birthplace of Cormac Mac Art, last resting place of Diar- maid and Grainne, is linked to Ben Bulben, named for Gulban a brother of Nial of the Nine Hostages, in the Peace in Our Time death of Diarmaid by Fionn during the treacherous Boar Hunt; while The scourge of war goes on and on Carraig na Spainneach in Streedagh Bay in the shadow of Ben Bulben is Devastating countries far and near. a reminder of the galleon of the A people depressed cry out for peace Spanish Armada wrecked on it in When will the bombings and killing. cease? 1588 and the deceit of Cuellar the The homeless, the hungry, those crippled by strife Spanish Captain befriended by Mac- Just sale for a chance to lead a normal Life. Clancy in his island castle on Lough Nuclear war heads bring sorrow and pain Melvin. Moyturra overlooking Lough Let us replace them with something humane. Arrow scene of the prehistoric Battle When will world Leaders Listen - of Moytura between the Firbolgs and Or will the killings go on? the Tuatha De Dananns and the Instead of weapons of war Megalithic cemetry of Carrowmore Let's create instruments of peace. -

Celtic Egyptians: Isis Priests of the Lineage of Scota

Celtic Egyptians: Isis Priests of the Lineage of Scota Samuel Liddell MacGregor Mathers – the primary creative genius behind the famous British occult group, the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn – and his wife Moina Mathers established a mystery religion of Isis in fin-de-siècle Paris. Lawrence Durdin-Robertson, his wife Pamela, and his sister Olivia created the Fellowship of Isis in Ireland in the early 1970s. Although separated by over half a century, and not directly associated with each other, both groups have several characteristics in common. Each combined their worship of an ancient Egyptian goddess with an interest in the Celtic Revival; both claimed that their priestly lineages derived directly from the Egyptian queen Scota, mythical foundress of Ireland and Scotland; and both groups used dramatic ritual and theatrical events as avenues for the promulgation of their Isis cults. The Parisian Isis movement and the Fellowship of Isis were (and are) historically-inaccurate syncretic constructions that utilised the tradition of an Egyptian origin of the peoples of Scotland and Ireland to legitimise their founders’ claims of lineal descent from an ancient Egyptian priesthood. To explore this contention, this chapter begins with brief overviews of Isis in antiquity, her later appeal for Enlightenment Freemasons, and her subsequent adoption by the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn. It then explores the Parisian cult of Isis, its relationship to the Celtic Revival, the myth of the Egyptian queen Scota, and examines the establishment of the Fellowship of Isis. The Parisian mysteries of Isis and the Fellowship of Isis have largely been overlooked by critical scholarship to date; the use of the medieval myth of Scota by the founders of these groups has hitherto been left unexplored. -

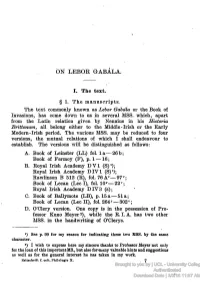

ON LEBOR GABALA. I. the Text

ON LEBOR GABALA. I. The text. § 1. The manuscripts. The text commonly known as Lebor Gabala or the Book of Invasions, has come down to us in several MSS. which, apart from the Latin relation given by Nennius in his Historia Brittomim, all belong either to the Middle-Irish or the Early Modern-Irish period. The various MSS. may be reduced to four versions, the mutual relations of which I shall endeavour to establish. The versions will be distinguished as follows: A. Book of Leinster (LL) fol. la—26b; Book of Fermoy (F), p. 1 —16; B. Royal Irish Academy DVI (S)1); Royal Irish Academy DIV1 (S)1); Rawlinson B 512 (R), fol. 76 Av— 97v; Book of Lecan (Lee I), fol. 10r—22v; Royal Irish Academy DIV3 (s); C. Book of Ballymote (LB), p. 15a—51 a; Book of Lecan (Lee H), fol. 264r—302v; D. OOlery version. One copy is in the possession of Pro- fessor Kuno Meyer2), while the R.I. A. has two other MSS. in the handwriting of O'Clerys. *) See p. 99 for my reason for indicating these two MSS. by the same character. 2) I wish to express here my sincere thanks to Professor Meyer not only for the loan of this important MS., but also formany valuable hints and suggestions as well as for the general interest he has taken in my work. Zeitschrift f. celt. Philologie X. 7 Brought to you by | UCL - University College London Authenticated Download Date | 3/3/16 11:57 AM OS A. G. VAN HAMEL, § 2. -

Fairy and Folk Tales of the Irish Peasantry, by 1

Fairy and Folk Tales of the Irish Peasantry, by 1 Fairy and Folk Tales of the Irish Peasantry, by William Butler Yeats This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org Title: Fairy and Folk Tales of the Irish Peasantry Author: William Butler Yeats Editor: William Butler Yeats Release Date: October 28, 2010 [EBook #33887] Language: English Fairy and Folk Tales of the Irish Peasantry, by 2 Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK FAIRY AND FOLK TALES *** Produced by Larry B. Harrison, Brian Foley and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive/American Libraries.) FAIRY AND FOLK TALES OF THE IRISH PEASANTRY. EDITED AND SELECTED BY W. B. YEATS. THE WALTER SCOTT PUBLISHING CO., LTD. LONDON AND FELLING-ON-TYNE. NEW YORK: 3 EAST 14TH STREET. INSCRIBED TO MY MYSTICAL FRIEND, G. R. CONTENTS. THE TROOPING FAIRIES-- PAGE The Fairies 3 Frank Martin and the Fairies 5 The Priest's Supper 9 The Fairy Well of Lagnanay 13 Teig O'Kane and the Corpse 16 Paddy Corcoran's Wife 31 Cusheen Loo 33 The White Trout; A Legend of Cong 35 The Fairy Thorn 38 The Legend of Knockgrafton 40 A Donegal Fairy 46 CHANGELINGS-- The Brewery of Egg-shells 48 The Fairy Nurse 51 Jamie Freel and the Young Lady 52 The Stolen Child 59 THE MERROW-- -

ML 4080 the Seal Woman in Its Irish and International Context

Mar Gur Dream Sí Iad Atá Ag Mairiúint Fén Bhfarraige: ML 4080 the Seal Woman in Its Irish and International Context The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Darwin, Gregory R. 2019. Mar Gur Dream Sí Iad Atá Ag Mairiúint Fén Bhfarraige: ML 4080 the Seal Woman in Its Irish and International Context. Doctoral dissertation, Harvard University, Graduate School of Arts & Sciences. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:42029623 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA Mar gur dream Sí iad atá ag mairiúint fén bhfarraige: ML 4080 The Seal Woman in its Irish and International Context A dissertation presented by Gregory Dar!in to The Department of Celti# Literatures and Languages in partial fulfillment of the re%$irements for the degree of octor of Philosophy in the subje#t of Celti# Languages and Literatures (arvard University Cambridge+ Massa#husetts April 2019 / 2019 Gregory Darwin All rights reserved iii issertation Advisor: Professor Joseph Falaky Nagy Gregory Dar!in Mar gur dream Sí iad atá ag mairiúint fén bhfarraige: ML 4080 The Seal Woman in its Irish and International Context4 Abstract This dissertation is a study of the migratory supernatural legend ML 4080 “The Mermaid Legend” The story is first attested at the end of the eighteenth century+ and hundreds of versions of the legend have been colle#ted throughout the nineteenth and t!entieth centuries in Ireland, S#otland, the Isle of Man, Iceland, the Faroe Islands, Norway, S!eden, and Denmark. -

Espelhos Distorcidos: O Romance at Swim- Two-Birds De Flann O'brien E a Tradição Literária Irlandesa

Universidade de Brasília Instituto de Letras Departamento de Teoria Literária e Literaturas Paweł Hejmanowski Espelhos Distorcidos: o Romance At Swim- Two-Birds de Flann O'Brien e a Tradição Literária Irlandesa Tese apresentada ao Programa de Pós-Graduação em Literatura para obtenção do título de Doutor, elaborada sob orientação da Profa. Dra. Cristina Stevens. Brasília 2011 IN MEMORIAM PROFESSOR ANDRZEJ KOPCEWICZ 2 Agradeço a minha colega Professora Doutora Cristina Stevens. A conclusão do presente estudo não teria sido possível sem sua gentileza e generosidade. 3 RESUMO Esta tese tem como objeto de análise o romance At Swim-Two-Birds (1939) do escritor irlandês Flann O’Brien (1911-1966). O romance pode ser visto, na perspectiva de hoje, como uma das primeiras tentativas de se implementar a poética de ficção autoconsciente e metaficção na literatura ocidental. Publicado na véspera da 2ª Guerra, o livro caiu no esquecimento até ser re-editado em 1960. A partir dessa data, At Swim-Two-Birds foi adquirindo uma reputação cult entre leitores e despertando o interesse crítico. Ao lançar mão do conceito mise en abyme de André Gide, o presente estudo procura mapear os textos dos quais At Swim-Two-Birds se apropria para refletí-los de forma distorcida dentro de sua própria narrativa. Estes textos vão desde narrativas míticas e históricas, passam pela poesia medieval e vão até os meados do século XX. Palavras-chave: Intertextualidade, Mis en abyme, Literatura e História, Romance Irlandês do séc. XX, Flann O’Brien. ABSTRACT The present thesis analyzes At Swim-Two-Birds, the first novel of the Irish author Flann O´Brien (1911-1966). -

Historias Misteriosas De Los Celtas

Historias misteriosas de los celtas Run Futthark HISTORIAS MISTERIOSAS DE LOS CELTAS A pesar de haber puesto el máximo cuidado en la redacción de esta obra, el autor o el editor no pueden en modo alguno res- ponsabilizarse por las informaciones (fórmulas, recetas, técnicas, etc.) vertidas en el texto. Se aconseja, en el caso de proble- mas específicos —a menudo únicos— de cada lector en particular, que se consulte con una persona cualificada para obtener las informaciones más completas, más exactas y lo más actualizadas posible. DE VECCHI EDICIONES, S. A. Traducción de Nieves Nueno Cobas. Fotografías de la cubierta: arriba, Tumulus gravinis © S. Rasmussen/Diaporama; abajo, Menhir de Poulnabrone, Burren, Irlanda © A. Lorgnier/Diaporama. © De Vecchi Ediciones, S. A. 2012 Diagonal 519-521, 2º - 08029 Barcelona Depósito Legal: B. 15.000-2012 ISBN: 978-17-816-0434-2 Editorial De Vecchi, S. A. de C. V. Nogal, 16 Col. Sta. María Ribera 06400 Delegación Cuauhtémoc México Reservados todos los derechos. Ni la totalidad ni parte de este libro puede reproducirse o trasmitirse por ningún procedimiento electrónico o mecánico, incluyendo fotocopia, grabación magnética o cualquier almacenamiento de información y sistema de recuperación, sin permiso es- crito de DE VECCHI EDICIONES. ÍNDICE INTRODUCCIÓN . 11 LOS ORÍGENES DE LOS CELTAS . 13 Los ligures . 13 Aparición de los celtas . 15 LAS MISTERIOSAS TRIBUS DE LA DIOSA DANA . 19 Los luchrupans . 19 Los fomorianos . 20 Desembarco en Irlanda, «tierra de cólera» . 23 Contra los curiosos fomorianos . 24 Segunda batalla de Mag Tured . 25 Grandeza y decadencia . 27 La presencia de Lug . 29 El misterio de los druidas. -

English As We Speak It in Ireland

ENGLISH AS WE SPEAK IT IN IRELAND. ENGLISH AS WE SPEAI^ IT IN IRELAND P. W. JOYCE, LLD., T.O.D., M.R.I.A. One of the Commissioners for the Publication of the Ancient Laws of Ireland Late Principal of the Government Training College, Marlbcrough Street, Dublin Late President of the Royal Society of Antiquaries, Ireland THE LIFE OF A PEOPLE IS PICTURED IN THEIR SPEECH. LONDON : LONGMANS, GREEN, & CO. DUBLIN: M. H. GILL & SON, LTD. i\ 1910 . b PEEFACE. THIS book deals with the Dialect of the English Language that is spoken in Ireland. As the Life of a people according to our motto is pictured in their speech, our picture ought to be a good one, for two languages were concerned in it Irish and English. The part played by each will be found specially set forth in and VII and in farther detail Chapters IV ; throughout the whole book. The articles and pamphlets that have already appeared on this interesting subject which are described below are all short. Some are full of keen observation but are lists ; very many mere of dialectical words with their meanings. Here for the first time in this little volume of mine our Anglo-Irish Dialect is subjected to detailed analysis and systematic classification. I have been collecting materials for this book for more than not indeed twenty years ; by way of constant work, but off and on as detailed below. The sources from which these materials were directly derived are mainly the following. First. My own memory is a storehouse both of idiom and for the reason vocabulary ; good that from childhood to early manhood I spoke like those among whom I lived the rich dialect VI PREFACE. -

The Mast of Macha: the Celtic Irish and the War Goddess of Ireland

Catherine Mowat: Barbara Roberts Memorial Book Prize Winner, 2003 THE 'MAST' OF MACHA THE CELTIC IRISH AND THE WAR GODDESS OF IRELAND "There are rough places yonder Where men cut off the mast of Macha; Where they drive young calves into the fold; Where the raven-women instigate battle"1 "A hundred generous kings died there, - harsh, heaped provisions - with nine ungentle madmen, with nine thousand men-at-arms"2 Celtic mythology is a brilliant shouting turmoil of stories, and within it is found a singularly poignant myth, 'Macha's Curse'. Macha is one of the powerful Morrigna - the bloody Goddesses of War for the pagan Irish - but the story of her loss in Macha's Curse seems symbolic of betrayal on two scales. It speaks of betrayal on a human scale. It also speaks of betrayal on a mythological one: of ancient beliefs not represented. These 'losses' connect with a proposal made by Anne Baring and Jules Cashford, in The Myth of The Goddess: Evolution of an Image, that any Goddess's inherent nature as a War Goddess reflects the loss of a larger, more powerful, image of a Mother Goddess, and another culture.3 This essay attempts to describe Macha and assess the applicability of Baring and Cashford's argument in this particular case. Several problems have arisen in exploring this topic. First, there is less material about Macha than other Irish Goddesses. Second, the fertile and unique synergy of cultural beliefs created by the Celts4 cannot be dismissed and, in a short paper, a problem exists in balancing what Macha meant to her people with the broader implications of the proposal made by Baring and Cashford. -

A Comparison of Mythological Traditions from Ireland and Iceland

THE ENCHANTED ISLANDS: A COMPARISON OF MYTHOLOGICAL TRADITIONS FROM IRELAND AND ICELAND A Pro Gradu Thesis by Katarzyna Herd Department of English 2008 JYVÄSKYLÄN YLIOPISTO Tiedekunta – Faculty Laitos – Department Humanistinen tiedekunta Englanninkielen laitos Tekijä – Author Katarzyna Herd Työn nimi – Title The Enchanted Islands: A comparison of mythological traditions from Ireland and Iceland Oppiaine – Subject Työn laji – Level Englanninkieli Pro gradu -tutkielma Aika – Month and year Sivumäärä – Number of pages Huhtikuussa 2008 124 Tiivistelmä – Abstract Vertailen tutkielmassani keskenään kelttiläistä ja skandinaavista mytologiaa. Molemmilla maailmankatsomuksilla uskotaan olevan juuret samassa indoeurooppalaisessa lähteessä ja ne ovat olleet historian aikana jatkuvasti tekemisissä toistensa kanssa. Tästä johtuen niiden uskotaan olevan samankaltaisia rakenteeltaan ja sisällöltään. Tutkielman lähtökohtana on, että mytologioiden samasta alkuperästä huolimatta ne ovat kehittäneet omat, toisistaan riippumattomat maailmankuvat. Analyysin päälähteitä ovat englanninkieliset käännökset keskiaikaisista teksteistä, kuten ”Book of Invasions”, Proosa-Edda ja Runo-Edda, sekä Crosslay-Hollandin ja P.B. Ellisin kirjaamat myytit. Kriittisen tarkastelun kohteena ovat myös muun muassa Hermin, Eliaden ja MacCullochin esittämät teoriat mytologioiden synnystä ja tarkoituksesta. Teorioiden ja tekstien vertailu antaa ymmärtää, että molemmat mytologiat kantavat samankaltaisia indoeurooppalaisille isäkulttuureille tyypillisiä maskuliinisia elementtejä, mutta