Celtic Egyptians: Isis Priests of the Lineage of Scota

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Irish Children's Literature and the Poetics of Memory, 1892-2016

Irish Children’s Literature and the Poetics of Memory, 1892-2016 A Thesis submitted to the School of English at the University of Dublin, Trinity College, for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy. February 2019 Rebecca Ann Long I declare that this thesis has not been submitted as an exercise for a degree at this or any other university and it is entirely my own work. I agree to deposit this thesis in the University’s open access institutional repository or allow the Library to do so on my behalf, subject to Irish Copyright Legislation and Trinity College Library conditions of use and acknowledgement. _________________________________ Rebecca Long February 2019 TABLE OF CONTENTS SUMMARY………………………………………………………………………………..i ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS……………………………………………………………....iii INTRODUCTION………………………………………………………………………....4 CHAPTER ONE: RETRIEVING……………………………………………………………………………29 CHAPTER TWO: RE- TELLING……………………………………………………………………………...…64 CHAPTER THREE: REMEMBERING……………………………………………………………………....106 CHAPTER FOUR: RE- IMAGINING………………………………………………………………………........158 CONCLUSION…………………………………………………………………..……..210 WORKS CITED………………………….…………………………………………………….....226 Summary This thesis explores the recurring patterns of Irish mythological narratives that influence literature produced for children in Ireland following the Celtic Revival and into the twenty- first century. A selection of children’s books published between 1892 and 2016 are discussed with the aim of demonstrating the development of a pattern of retrieving, re-telling, remembering and re-imagining myths -

The Celtic Revival in English Literature, 1760-1800

ZOh. jU\j THE CELTIC REVIVAL IN ENGLISH LITERATURE LONDON : HUMPHREY MILFORD OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS The "Bard The Celtic Revival in English Literature 1760 — 1800 BY EDWARD D. SNYDER B.A. (Yale), Ph.D. (Harvard) CAMBRIDGE HARVARD UNIVERSITY PRESS 1923 COPYRIGHT, 1923 BY HARVARD UNIVERSITY PRESS PRINTED AT THE HARVARD UNIVERSITY PRESS CAMBRIDGE, MASS., U. S. A. PREFACE The wholesome tendency of modern scholarship to stop attempting a definition of romanticism and to turn instead to an intimate study of the pre-roman- tic poets, has led me to publish this volume, on which I have been intermittently engaged for several years. In selecting the approximate dates 1760 and 1800 for the limits, I have been more arbitrary in the later than in the earlier. The year 1760 has been selected because it marks, roughly speaking, the beginning of the Celtic Revival; whereas 1800, the end of the century, is little more than a con- venient place for breaking off a history that might have been continued, and may yet be continued, down to the present day. Even as the volume has been going through the press, I have found many new items from various obscure sources, and I am more than ever impressed with the fact that a collection of this sort can never be complete. I have made an effort, nevertheless, to show in detail what has been hastily sketched in countless histories of literature — the nature and extent of the Celtic Revival in the late eighteenth century. Most of the material here presented is now pub- lished for the first time. -

Celticism, Internationalism and Scottish Identity Three Key Images in Focus

Celticism, Internationalism and Scottish Identity Three Key Images in Focus Frances Fowle The Scottish Celtic Revival emerged from long-standing debates around language and the concept of a Celtic race, a notion fostered above all by the poet and critic Matthew Arnold.1 It took the form of a pan-Celtic, rather than a purely Scottish revival, whereby Scotland participated in a shared national mythology that spilled into and overlapped with Irish, Welsh, Manx, Breton and Cornish legend. Some historians portrayed the Celts – the original Scottish settlers – as pagan and feckless; others regarded them as creative and honorable, an antidote to the Industrial Revolution. ‘In a prosaic and utilitarian age,’ wrote one commentator, ‘the idealism of the Celt is an ennobling and uplifting influence both on literature and life.’2 The revival was championed in Edinburgh by the biologist, sociologist and utopian visionary Patrick Geddes (1854–1932), who, in 1895, produced the first edition of his avant-garde journal The Evergreen: a Northern Seasonal, edited by William Sharp (1855–1905) and published in four ‘seasonal’ volumes, in 1895– 86.3 The journal included translations of Breton and Irish legends and the poetry and writings of Fiona Macleod, Sharp’s Celtic alter ego. The cover was designed by Charles Hodge Mackie (1862– 1920) and it was emblazoned with a Celtic Tree of Life. Among 1 On Arnold see, for example, Murray Pittock, Celtic Identity and the Brit the many contributors were Sharp himself and the artist John ish Image (Manchester: Manches- ter University Press, 1999), 64–69 Duncan (1866–1945), who produced some of the key images of 2 Anon, ‘Pan-Celtic Congress’, The the Scottish Celtic Revival. -

Cult of Isis

Interpreting Early Hellenistic Religion PAPERS AND MONOGRAPHS OF THE FINNISH INSTITUTE AT ATHENS VOL. III Petra Pakkanen INTERPRETING EARL Y HELLENISTIC RELIGION A Study Based on the Mystery Cult of Demeter and the Cult of Isis HELSINKI 1996 © Petra Pakkanen and Suomen Ateenan-instituutin saatiO (Foundation of the Finnish Institute at Athens) 1996 ISSN 1237-2684 ISBN 951-95295-4-3 Printed in Greece by D. Layias - E. Souvatzidakis S.A., Athens 1996 Cover: Portrait of a priest of Isis (middle of the 2nd to middle of the 1st cent. BC). American School of Classical Studies at Athens: Agora Excavations. Inv. no. S333. Photograph Craig Mauzy. Sale: Bookstore Tiedekirja, Kirkkokatu 14, FIN-00170 Helsinki, Finland Contents Acknowledgements I. Introduction 1. Problems 1 2. Cults Studied 2 3. Geographical Confines 3 4. Sources and an Evaluation of Sources 5 11. Methodology 1. Methodological Approach to the History of Religions 13 2. Discussion of Tenninology 19 3. Method for Studying Religious and Social Change 20 Ill. The Cults of Demeter and Isis in Early Hellenistic Athens - Changes in Religion 1. General Overview of the Religious Situation in Athens During the Early Hellenistic Period: Typology of Religious Cults 23 2. Cult of Demeter: Eleusinian Great Mysteries 29 3. Cult of Isis 47 Table 1 64 IV. Problem of the Mysteries 1. Definition of the Tenn 'Mysteries' 65 2. Aspects of the Mysteries 68 3. Mysteries in Athens During the Early Hellenistic Period and a Comparison to Those of Rome in the Third Century AD 71 4. Emergence of the Mysteries ofIsis in Greece 78 Table 2 83 V. -

Brill's Companion to Aphrodite / Edited by Amy C

Brill’s Companion to Aphrodite Edited by Amy C. Smith and Sadie Pickup LEIDEN • BOSTON 2010 On the cover:AnAtticblack-!gure amphora, featuring Aphrodite and Poseidon, ca. 520"#. London, British Museum B254. Drawing a$er Lenormant, de Witte, Élite des monuments céramographiques. Matériaux pour l’histoire des religions et des moeurs de l’antiquité (Paris, 1844–1861), 3, pl. 15. %is book is printed on acid-free paper. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Brill's companion to aphrodite / edited by Amy C. Smith & Sadie Pickup. p. cm. Emerged from a conference at the University of Reading, May 8-10, 2008. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-90-04-18003-1 (hardback : alk. paper) 1. Aphrodite (Greek deity)–Congresses. I. Smith, Amy Claire, 1966- II. Title. BL820.V5B74 2010 292.2'114–dc22 2009052569 ISSN 1872-3357 ISBN 978 9004 18003 1 Copyright 2010 by Koninklijke Brill NV,Leiden, %eNetherlands. Koninklijke Brill NV incorporates the imprints Brill, Hotei Publishing, IDC Publishers, Martinus Nijho& Publishers and VSP. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, translated, stored in aretrievalsystem,ortransmittedinanyformorbyanymeans,electronic,mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior written permission from the publisher. Brill has made all reasonable e&orts to trace all right holders to any copyrighted material used in this work. In cases where these e&orts have not been successful the publisher welcomes communications from copyright holders, so that the appropriate acknowledgements can be made in future editions, and to settle other permission matters. Authorization to photocopy items for internal or personal use is granted by Koninklijke Brill NV provided that the appropriate fees are paid directly to %eCopyrightClearanceCenter, 222 Rosewood Drive, Suite 910, Danvers, MA 01923, USA. -

THE MYTHOLOGY, TRADITIONS and HISTORY of Macdhubhsith

THE MYTHOLOGY, TRADITIONS and HISTORY OF MacDHUBHSITH ― MacDUFFIE CLAN (McAfie, McDuffie, MacFie, MacPhee, Duffy, etc.) VOLUME 2 THE LANDS OF OUR FATHERS PART 2 Earle Douglas MacPhee (1894 - 1982) M.M., M.A., M.Educ., LL.D., D.U.C., D.C.L. Emeritus Dean University of British Columbia This 2009 electronic edition Volume 2 is a scan of the 1975 Volume VII. Dr. MacPhee created Volume VII when he added supplemental data and errata to the original 1792 Volume II. This electronic edition has been amended for the errata noted by Dr. MacPhee. - i - THE LIVES OF OUR FATHERS PREFACE TO VOLUME II In Volume I the author has established the surnames of most of our Clan and has proposed the sources of the peculiar name by which our Gaelic compatriots defined us. In this examination we have examined alternate progenitors of the family. Any reader of Scottish history realizes that Highlanders like to move and like to set up small groups of people in which they can become heads of families or chieftains. This was true in Colonsay and there were almost a dozen areas in Scotland where the clansman and his children regard one of these as 'home'. The writer has tried to define the nature of these homes, and to study their growth. It will take some years to organize comparative material and we have indicated in Chapter III the areas which should require research. In Chapter IV the writer has prepared a list of possible chiefs of the clan over a thousand years. The books on our Clan give very little information on these chiefs but the writer has recorded some probable comments on his chiefship. -

The Celtic Revival in Scotland Timetable

The Celtic Revival in Scotland Timetable Thursday 1 May 2014 1:00–1:30: Registration and Reception 1:30–1:50: Welcome and opening remarks Panel 1 Panel 2 2:00–2:30 Nicola Gordon Bowe, ‘Embroideries Liam Mac Mathúna, Douglas Hyde and out of old mythologies’: analogies between the wider world of the Gael inspiration and practice in the arts of the Celtic Revival in Dublin and Edinburgh 2:30–3:00 Sally Foster, Celtic collections and Wilson McLeod, Gaelic learners and the imperial connections: the V&A, language movement, 1870-1930 Scotland and the multiplication of plaster casts of ‘Celtic crosses’ 3:00–3:30 Elizabeth Cumming, Here Come the Rob Dunbar, Was there a Celtic Revival Celts! The Scottish National Pageant of in Canada? 1908 3:30–4:00 pm: Tea Panel 3 Panel 4 4:00–4:30 Stuart Eydmann, The harp as an Stuart Wallace, John Stuart Blackie and emblem of the Celtic Revival, with the Celtic Revival in Scotland particular reference to Scotland 4:30–5.15 John Purser, ‘The Lay of the Last Bernhard Maier, ‘Widening the Jacket’: Minstrel? Don’t count on it’: The Celtic John Stuart Blackie and Germany Revival in Scottish Classical Music 5:15–5:30: Break 5:30–6:30: Murdo Macdonald, The Art of the Scottish Celtic Revival Hawthornden Lecture Theatre, Scottish National Gallery 7:00–8:30: Drinks reception and private view of A Wide New Kingdom: The Celtic Revival in Scotland, Talbot Rice Gallery. Friday 2 May 2014 10:00–11:00: Donald Meek, The Celtic Revival and the beginnings of Celtic scholarship in Scotland Hawthornden Lecture Theatre, Scottish -

The Founding of Ireland and Scotland

HOW IRELAND AND SCOTLAND WAS SETTLED A Jewish tribe left Egypt and settled in Ireland. They were called the Milesians and were the ruling class of Ireland. They evidently moved into Scotland and the throne of Ireland was moved under the reign of King Fergus. The Scotland lived in the mountain area of Scotland and were called the Scots. This article will proof that the Scotish people were a tribe of the Jews and they held the sceptre. The Jewish in Palestine did not have the sceptre after the captivity of Judah 500 B.C. Brief history of Ancient Ireland 1709 B.C. -The Parthalonnians are credited for being the first settlers of Ireland. The Parthalonians, whoever they may have been, ruled Ireland intermittently until 1709 BCE, when a tragedy befell them at the hands of Phoenician Formorians. 1492 B.C. – Nemedians were the Fir Bolgs. The island was then invaded by Nemedians from Scythia who lived in Ireland. The Nemedians were ruled by the Formorians for much of this period. A portion of the Nemedians escaped during their sojourn in the land and returned in 1492 BC as the Fir- Bolgs. The FirBlogs were later given as a place of settlement the Aran Islands under a King named Aengus. Formanians settled on another island. 1456 B.C -.DAN IN NORTH IRELAND Tuatha De Danaan settled Northern Ireland. The immigration of Dan to Ireland came in waves. A contingent of the famous Tuatha de Danaan (“Tribe of Dan”) arrived in Ireland 1456 B.C. and ruled for 440 years until 1016 BCE. -

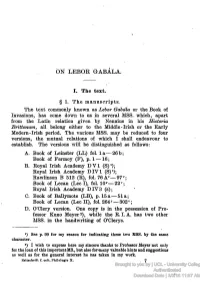

ON LEBOR GABALA. I. the Text

ON LEBOR GABALA. I. The text. § 1. The manuscripts. The text commonly known as Lebor Gabala or the Book of Invasions, has come down to us in several MSS. which, apart from the Latin relation given by Nennius in his Historia Brittomim, all belong either to the Middle-Irish or the Early Modern-Irish period. The various MSS. may be reduced to four versions, the mutual relations of which I shall endeavour to establish. The versions will be distinguished as follows: A. Book of Leinster (LL) fol. la—26b; Book of Fermoy (F), p. 1 —16; B. Royal Irish Academy DVI (S)1); Royal Irish Academy DIV1 (S)1); Rawlinson B 512 (R), fol. 76 Av— 97v; Book of Lecan (Lee I), fol. 10r—22v; Royal Irish Academy DIV3 (s); C. Book of Ballymote (LB), p. 15a—51 a; Book of Lecan (Lee H), fol. 264r—302v; D. OOlery version. One copy is in the possession of Pro- fessor Kuno Meyer2), while the R.I. A. has two other MSS. in the handwriting of O'Clerys. *) See p. 99 for my reason for indicating these two MSS. by the same character. 2) I wish to express here my sincere thanks to Professor Meyer not only for the loan of this important MS., but also formany valuable hints and suggestions as well as for the general interest he has taken in my work. Zeitschrift f. celt. Philologie X. 7 Brought to you by | UCL - University College London Authenticated Download Date | 3/3/16 11:57 AM OS A. G. VAN HAMEL, § 2. -

On the Orientation of the Avenue of Sphinxes in Luxor Amelia Carolina Sparavigna

On the orientation of the Avenue of Sphinxes in Luxor Amelia Carolina Sparavigna To cite this version: Amelia Carolina Sparavigna. On the orientation of the Avenue of Sphinxes in Luxor. Philica, Philica, 2018. hal-01700520 HAL Id: hal-01700520 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01700520 Submitted on 4 Feb 2018 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. On the orientation of the Avenue of Sphinxes in Luxor Amelia Carolina Sparavigna (Department of Applied Science and Technology, Politecnico di Torino) Abstract The Avenue of Sphinxes is a 2.8 kilometres long Avenue linking Luxor and Karnak temples. This avenue was the processional road of the Opet Festival from the Karnak temple to the Luxor temple and the Nile. For this Avenue, some astronomical orientations had been proposed. After the examination of them, we consider also an orientation according to a geometrical planning of the site, where the Avenue is the diagonal of a square, a sort of best-fit straight line in a landscape constrained by the presence of temples, precincts and other processional avenues. The direction of the rising of Vega was probably used as reference direction for the surveying. -

![Archons (Commanders) [NOTICE: They Are NOT Anlien Parasites], and Then, in a Mirror Image of the Great Emanations of the Pleroma, Hundreds of Lesser Angels](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8862/archons-commanders-notice-they-are-not-anlien-parasites-and-then-in-a-mirror-image-of-the-great-emanations-of-the-pleroma-hundreds-of-lesser-angels-438862.webp)

Archons (Commanders) [NOTICE: They Are NOT Anlien Parasites], and Then, in a Mirror Image of the Great Emanations of the Pleroma, Hundreds of Lesser Angels

A R C H O N S HIDDEN RULERS THROUGH THE AGES A R C H O N S HIDDEN RULERS THROUGH THE AGES WATCH THIS IMPORTANT VIDEO UFOs, Aliens, and the Question of Contact MUST-SEE THE OCCULT REASON FOR PSYCHOPATHY Organic Portals: Aliens and Psychopaths KNOWLEDGE THROUGH GNOSIS Boris Mouravieff - GNOSIS IN THE BEGINNING ...1 The Gnostic core belief was a strong dualism: that the world of matter was deadening and inferior to a remote nonphysical home, to which an interior divine spark in most humans aspired to return after death. This led them to an absorption with the Jewish creation myths in Genesis, which they obsessively reinterpreted to formulate allegorical explanations of how humans ended up trapped in the world of matter. The basic Gnostic story, which varied in details from teacher to teacher, was this: In the beginning there was an unknowable, immaterial, and invisible God, sometimes called the Father of All and sometimes by other names. “He” was neither male nor female, and was composed of an implicitly finite amount of a living nonphysical substance. Surrounding this God was a great empty region called the Pleroma (the fullness). Beyond the Pleroma lay empty space. The God acted to fill the Pleroma through a series of emanations, a squeezing off of small portions of his/its nonphysical energetic divine material. In most accounts there are thirty emanations in fifteen complementary pairs, each getting slightly less of the divine material and therefore being slightly weaker. The emanations are called Aeons (eternities) and are mostly named personifications in Greek of abstract ideas. -

The Foot of Sarapis

THE FOOT OF SARAPIS I. PRIMARY MONU\MENTS Anyone who collects the monuiments associated with Mithras, as F. Cumont did, or with the " Egyptian " gods, as T. A. Brady is doing, or with the " Syrian " gods, as F. R. Walton is doing, will come upon a curious type of monument-the grotesque, snake-entwined, bust-crowned, gigantic Foot of Sarapis. In no other ancient or modern cult, so far as we are aware, is there anything quite like these objects. The fact that it was a symbol on Imperial Roman coinage indicates that in its own day as well the Foot of Sarapis was felt to be distinctive. In mnodernscholarly writings there is no lack of references to these monuments (we have tried to record all references). It happens, however, that no one has had in hand at one timie the materials necessary for a passable study of any one of them, let alone a study of all together. The accidental discovery, in 1936, of another Foot, the first and only example known in Athens, and the largest known anywhere, led us to collect evidence on the others. One would expect to find that ntumerous examples had survived. Writing in 1820, H. Meyer knew only one example of such feet carved in the round. The number has increased slowly. In the present study we have tried to assemble all the feet in the round which are positivelv attested as being associated with Sarapis. and we have found onlv five. Dotubtless some few more exist unpublished, but not, we believe, more than a fev.