Soho Steam Engines the First Engineering Slide Rule and the Evolution of Excise Rules

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Intellectual Property Center, 28 Upper Mckinley Rd. Mckinley Hill Town Center, Fort Bonifacio, Taguig City 1634, Philippines Tel

Intellectual Property Center, 28 Upper McKinley Rd. McKinley Hill Town Center, Fort Bonifacio, Taguig City 1634, Philippines Tel. No. 238-6300 Website: http://www.ipophil.gov.ph e-mail: [email protected] Publication Date: August 10, 2015 1 ALLOWED MARKS PUBLISHED FOR OPPOSITION ............................................................................................... 2 1.1 ALLOWED NATIONAL MARKS ....................................................................................................................................... 2 Intellectual Property Center, 28 Upper McKinley Rd. McKinley Hill Town Center, Fort Bonifacio, Taguig City 1634, Philippines Tel. No. 238-6300 Website: http://www.ipophil.gov.ph e-mail: [email protected] Publication Date: August 10, 2015 1 ALLOWED MARKS PUBLISHED FOR OPPOSITION 1.1 Allowed national marks Application No. Filing Date Mark Applicant Nice class(es) Number 25 June 1 4/2010/00006843 AIR21 GLOBAL AIR21 GLOBAL, INC. [PH] 35 and39 2010 20 2 4/2012/00011594 September AAA SUNQUAN LU [PH] 19 2012 11 May 3 4/2012/00501163 CACATIAN, LEUGIM D [PH] 25 2012 24 4 4/2012/00740257 September MIX N` MAGIC MICHAELA A TAN [PH] 30 2012 11 June NEUROGENESIS 5 4/2013/00006764 LBI BRANDS, INC. [CA] 32 2013 HAPPY WATER BABAYLAN SPA AND ALLIED 6 4/2013/00007633 1 July 2013 BABAYLAN 44 INC. [PH] 12 July OAKS HOTELS & M&H MANAGEMENT 7 4/2013/00008241 43 2013 RESORTS LIMITED [MU] 25 July DAIWA HOUSE INDUSTRY 8 4/2013/00008867 DAIWA HOUSE 36; 37 and42 2013 CO., LTD. [JP] 16 August ELLEBASY MEDICALE ELLEBASY MEDICALE 9 4/2013/00009840 35 2013 TRADING TRADING [PH] 9 THE PROCTER & GAMBLE 10 4/2013/00010788 September UNSTOPABLES 3 COMPANY [US] 2013 9 October BELL-KENZ PHARMA INC. -

Soho Depicted: Prints, Drawings and Watercolours of Matthew Boulton, His Manufactory and Estate, 1760-1809

SOHO DEPICTED: PRINTS, DRAWINGS AND WATERCOLOURS OF MATTHEW BOULTON, HIS MANUFACTORY AND ESTATE, 1760-1809 by VALERIE ANN LOGGIE A thesis submitted to The University of Birmingham for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Department of History of Art College of Arts and Law The University of Birmingham January 2011 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. ABSTRACT This thesis explores the ways in which the industrialist Matthew Boulton (1728-1809) used images of his manufactory and of himself to help develop what would now be considered a ‘brand’. The argument draws heavily on archival research into the commissioning process, authorship and reception of these depictions. Such information is rarely available when studying prints and allows consideration of these images in a new light but also contributes to a wider debate on British eighteenth-century print culture. The first chapter argues that Boulton used images to convey messages about the output of his businesses, to draw together a diverse range of products and associate them with one site. Chapter two explores the setting of the manufactory and the surrounding estate, outlining Boulton’s motivation for creating the parkland and considering the ways in which it was depicted. -

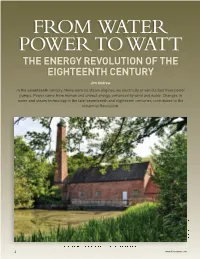

A Steam Issue-48Pp HWM

FROM WATER POWER TO WATT THE ENERGY REVOLUTION OF THE EIGHTEENTH CENTURY Jim Andrew In the seventeenth century, there were no steam engines, no electricity or vehicle fuel from petrol pumps. Power came from human and animal energy, enhanced by wind and water. Changes in water and steam technology in the late-seventeenth and eighteenth centuries contributed to the Industrial Revolution. © Birmingham Museums Trust Sarehole Mill. One of the two remaining water mills in the Birmingham area. 4 www.historywm.com FROM WATER POWER TO WATT ind power, as now, was limited by variations in the strength of the wind, making water the preferred reliable Wsource of significant power for regular activity. The Romans developed water wheels and used them for a variety of activities but the first definitive survey of water power in England was in the Doomsday Book c.1086. At that time, well over five-thousand mills were identified – most were the Norse design with a vertical shaft and horizontal disc of blades. Water-Wheel Technology Traditional water mills, with vertical wheels on horizontal shafts, were well established by the eighteenth century. Many were underpass designs where the water flowed under a wheel with paddles being pushed round by the flow. Over time, many mills adopted designs which had buckets, filled with water at various levels from quite low to the very top of the wheel. The power was extracted by the falling of the water from its entry point to where it was discharged. There was little systematic study of the efficiency of mill-wheel design in extracting energy from the water before the eighteenth century. -

Introduction: a Manufacturing People

1 Introduction: a manufacturing people ‘It will be seen that a manufacturing people is not so happy as a rural population, and this is the foretaste of becoming the “Workshop of the World”.’ Sir James Graham to Edward Herbert, 2nd Earl of Powis, 31 August 1842 ‘From this foul drain the greatest stream of human industry flows out to fertilise the whole world. From this filthy sewer pure gold flows. Here humanity attains its most complete development and its most brutish; here civilisation works its miracles, and civilised man is turned back almost into a savage.’ Alexis de Tocqueville on Manchester, 1835 ritain’s national census of 1851 reveals that just over one half of the economically active B population were employed in manufacturing (including mining and construction), while fewer than a quarter now worked the land. The making of textiles alone employed well over a million men and women. The number of factories, mines, metal-working complexes, mills and workshops had all multiplied, while technological innovations had vastly increased the number of, and improved the capabilities of, the various machines that were housed in them. Production and exports were growing, and the economic and social consequences of industrial development could be felt throughout the British Isles. The British had become ‘a manufacturing people’. These developments had not happened overnight, although many of the most momentous had taken place within living memory. By the 1850s commentators were already describing Dictionary, indeed, there is no definition whatever this momentous shift as an ‘industrial revolution’. relating to this type of phenomenon. Is it, therefore, The phrase obviously struck a chord, and is now really a help or a hindrance to rely on it to describe deeply ingrained. -

INDUSTRIAL REVOLUTION: SERIES ONE: the Boulton and Watt Archive, Parts 2 and 3

INDUSTRIAL REVOLUTION: SERIES ONE: The Boulton and Watt Archive, Parts 2 and 3 Publisher's Note - Part - 3 Over 3500 drawings covering some 272 separate engines are brought together in this section devoted to original manuscript plans and diagrams. Watt’s original engine was a single-acting device for producing a reciprocating stroke. It had an efficiency four times that of the atmospheric engine and was used extensively for pumping water at reservoirs, by brine works, breweries, distilleries, and in the metal mines of Cornwall. To begin with it played a relatively small part in the coal industry. In the iron industry these early engines were used to raise water to turn the great wheels which operated the bellows, forge hammers, and rolling mills. Even at this first stage of development it had important effects on output. However, Watt was extremely keen to make improvements on his initial invention. His mind had long been busy with the idea of converting the to and fro action into a rotary movement, capable of turning machinery and this was made possible by a number of devices, including the 'sun-and-planet', a patent for which was taken out in 1781. In the following year came the double-acting, rotative engine, in 1784 the parallel motion engine, and in 1788, a device known as the 'governor', which gave the greater regularity and smoothness of working essential in a prime mover for the more delicate and intricate of industrial processes. The introduction of the rotative engine was a momentous event. By 1800 Boulton and Watt had built and put into operation over 500 engines, a large majority being of the 'sun and planet type'. -

Modern Steam- Engine

CHAPTER III. THE ·DEVELOPJIENT OF THE .AfODERN STEAM-ENGINE. JAAIES WA1'T A1VD HIS OONTEJIPORARIES. THE wol'ld is now entering upon the Mechanical Epoch. There is noth ing in the future n1ore sure than the great tl'iu1nphs which thn.t epoch is to achieve. It has ah·eady u<Jvanced to some glorious conquests. '\Vhat111ira cle� of invention now crowd upon us I Look ab1·oad, and contemplate the infinite achieve1nents of the steam-power. And· yet we have only begun-we are but on tho threshold of this epoch.... What is it but ·the setting of the great distinctive seal upon the nineteenth century ?-an advertisement of the fact that society .hns risen to occupy a higher platfor1n than ever before ?-a proclamation f1·01n the high places, announcing honor, honor imn1ortal, to the �vorlunen who fill this world with beauty, comfort, and power-honor to he forever embahned in history, to be pet·petuated in monuments, to be written in the hearts of this and succeeding generations !-KENNEDY. I.-J w SECTION A?rlES .A.TT AND HIS INVENTIONS. \ • . THE success of the N ewcomen engine naturally attracted the attention of mechanics, and of scientific men as well, to the p9ssibility of making other applications of steam-power. The best men of the time gave much attention to tl1e subject, but, until ·James Watt began the work that has made him famous, nothing more ,vas done than to improve the proportions and slightly alter the details of the Ne,vco men and Calley engine, even by such skillful engineers as Brindley and Smeaton. -

Lives in Engineering

LIVES IN ENGINEERING John Scales Avery January 19, 2020 2 Contents 1 ENGINEERING IN THE ANCIENT WORLD 9 1.1 Megalithic structures in prehistoric Europe . .9 1.2 Imhotep and the pyramid builders . 15 1.3 The great wall of China . 21 1.4 The Americas . 25 1.5 Angkor Wat . 31 1.6 Roman engineering . 38 2 LEONARDO AS AN ENGINEER 41 2.1 The life of Leonardo da Vinci . 41 2.2 Some of Leonardo's engineering drawings . 49 3 THE INVENTION OF PRINTING 67 3.1 China . 67 3.2 Islamic civilization and printing . 69 3.3 Gutenberg . 74 3.4 The Enlightenment . 77 3.5 Universal education . 89 4 THE INDUSTRIAL REVOLUTION 93 4.1 Development of the steam engine . 93 4.2 Working conditions . 99 4.3 The slow acceptance of birth control in England . 102 4.4 The Industrial Revolution . 106 4.5 Technical change . 107 4.6 The Lunar Society . 111 4.7 Adam Smith . 113 4.8 Colonialism . 119 4.9 Trade Unions and minimum wage laws . 120 4.10 Rising standards of living . 125 4.11 Robber barons and philanthropists . 128 3 4 CONTENTS 5 CANALS, RAILROADS, BRIDGES AND TUNNELS 139 5.1 Canals . 139 5.2 Isambard Kingdon Brunel . 146 5.3 Some famous bridges . 150 5.4 The US Transcontinental Railway . 156 5.5 The Trans-Siberian railway . 158 5.6 The Channel Tunnel . 162 6 TELEGRAPH, RADIO AND TELEPHONE 171 6.1 A revolution in communication . 171 6.2 Ørsted, Amp`ereand Faraday . 174 6.3 Electromagnetic waves: Maxwell and Hertz . -

At the Soho Sites of Matthew Boulton and James Watt

WOMEN AND CHILD WORKERS AT THE SOHO SITES OF MATTHEW BOULTON AND JAMES WATT Caitlin Russell In the 1770s, a partnership developing practical steam power began between the English manufacturer, Matthew Boulton, and the Scottish steam engine inventor, James Watt. This partnership was successful and in 1796 they established a foundry in Smethwick, Birmingham, to have a specialised production unit for their steam engines. It joined Boulton’s Manufactory and Mint, in Handsworth, to form the Soho Sites. These enterprises contained a wide range of workers, including women and teenage boys. Documents kept by the company reveal the nature and extent of the relationship between employers and employees. Reproduced with the permission of the Library of Birmingham of the Library with the permission Reproduced Matthew Boulton’s Soho Manufactory, Handsworth near Birmingham, the home to several of his businesses from Bisset’s Magnificent Guide or Grand Copperplate Directory for the Town of Birmingham, 1808. WOMEN AND CHILD WORKERS AT THE SOHO SITES OF MATTHEW BOULTON AND JAMES WATT Women Workers Sometimes this red ink mentioned when money There is not a lot of evidence for women workers, but was ‘left off for club’, referring to the women’s one of the few tantalising pieces is provided by Dorothy division of the Soho Insurance Society, commonly Richardson, a contemporary who Courtesy of Assay Office Birmingham known as the Soho Sick Club, visited the factory in which provided 1770 and wrote a Manufactory detailed account of workers with a what she saw. Her limited, but evidence indicates progressive for the that there were time, version of women workers at the workers’ health Manufactory who have insurance.4 The women’s been hidden from history in division is only briefly the secondary sources. -

Landmarks in Mechanical Engineering

Page iii Landmarks in Mechanical Engineering ASME International History and Heritage Page iv Copyright © by Purdue Research Foundation. All rights reserved. 01 00 99 98 97 5 4 3 2 1 The paper used in this book meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences– Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.481992. Printed in the United States of America Design by inari Cover photo credits Front: Icing Research Tunnel, NASA Lewis Research Center; top inset, Saturn V rocket; bottom inset, WymanGordon 50,000ton hydraulic forging press (Courtesy Jet Lowe, Library of Congress Collections Back: top, Kaplan turbine; middle, Thomas Edison and his phonograph; bottom, "Big Brutus" mine shovel Unless otherwise indicated, all photographs and illustrations were provided from the ASME landmarks archive. Library of Congress Cataloginginpublication Data Landmarks in mechanical engineering/ASME International history and Heritage. p. cm Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN I557530939 (cloth:alk. paper).— ISBN I557530947 (pbk. : alk. paper) 1. Mechanical engineering—United States—History 2. Mechanical engineering—History. 1. American Society of Mechanical Engineers. History and Heritage Committee. TJ23.L35 1996 621'.0973—dc20 9631573 CIP Page v CONTENTS Preface xiii Acknowledgments xvii Pumping Introduction 1 Newcomen Memorial Engine 3 Fairmount Waterworks 5 Chesapeake & Delaware Canal Scoop Wheel and Steam Engines 8 Holly System of Fire Protection and Water Supply 10 Archimedean Screw Pump 11 Chapin Mine Pumping Engine 12 LeavittRiedler Pumping Engine 14 Sidebar: Erasmus D.Leavitt, Jr. 16 Chestnut Street Pumping Engine 17 Specification: Chestnut Street Pumping Engine 18 A. -

Birmingham Metallurgical Society Lectures and Papers

Birmingham Metallurgical Society Lectures and Papers Copper strip at IMI Volume I Metals and Alloys Editor: I.L. Dillamore Birmingham Metallurgical Society An Anthology of Papers reflecting the evolution of the subject of Metallurgy and the rise and fall of the associated industries in Birmingham. Represented by papers presented to the Society by National and International Experts and by major contributions made by Members of the Society. Volume I The Metals and Alloys Introduction The Birmingham Metallurgical Society was already seventeen years old when it was registered at Companies House. In those years the understanding of the behaviour of metals had advanced significantly, but still had a long way to go. The aim of the collection assembled in this and two following volumes is to show through the activities of the Society and its members how the subject of metallurgy evolved and how those companies that created the Midlands metal industry wax and waned. The Society was much involved in 1908 in the creation of a national organisation, The Institute of Metals, to serve the interests of the non-ferrous industries. The Institute's first office was in the University. In 1945 it was on an initiative of its members that a body was formed to give professional recognition to qualified metallurgists: the Institution of Metallurgists, which represented all metallurgists, both ferrous and non-ferrous. Many of the lectures in the first 50 years are shown as being before the 'Coordinated Societies'. These were the Birmingham Metallurgical Society, The South Staffordshire iron and Steel Institute and the local section of the Institute of Metals. -

Matthew Boulton and the Soho Mint Numismatic Circular April 1983 Volume XCI Number 3 P 78

MATTHEW BOULTON AND THE SOHO MINT: COPPER TO CUSTOMER by SUE TUNGATE A thesis submitted to The University of Birmingham for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Department of Modern History College of Arts and Law The University of Birmingham October 2010 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. ABSTRACT Matthew Boulton (1728-1809) is well known as an eighteenth-century industrialist, the founder of Soho Manufactory and the steam-engine business of Boulton and Watt. Less well known are his scientific and technical abilities in the field of metallurgy and coining, and his role in setting up the Soho Mint. The intention of this thesis is to focus on the coining activities of Matthew Boulton from 1787 until 1809, and to examine the key role he played in the modernisation of money. It is the result of an Arts and Humanities Research Council-funded collaboration with Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery, where, after examination of their extensive collection of coins, medals, tokens and dies produced at the Soho Mint, .research was used to produce a catalogue. -

{TEXTBOOK} the Soho Manufactory, Mint and Foundry, West Midlands

THE SOHO MANUFACTORY, MINT AND FOUNDRY, WEST MIDLANDS, 1761-1895 : WHERE BOULTON, WATT AND MURDOCH MADE HISTORY Author: George Demidowicz Number of Pages: 288 pages Published Date: 28 Jan 2021 Publisher: Oxbow Books Publication Country: Oxford, United Kingdom Language: English ISBN: 9781789255225 DOWNLOAD: THE SOHO MANUFACTORY, MINT AND FOUNDRY, WEST MIDLANDS, 1761-1895 : WHERE BOULTON, WATT AND MURDOCH MADE HISTORY The Soho Manufactory, Mint and Foundry, West Midlands, 1761-1895 : Where Boulton, Watt and Murdoch Made History PDF Book Upgraded features in the Canon EOS 70D include a new focusing technology that speeds up autofocus for video and live view shooting, a larger sensor, faster frame-by-frame shooting, and a wider ISO range This full-color guide explains how to take advantage of all the features; walks you through all the on- board controls, and shows how to shoot in auto mode Covers dSLR basics such as dialing in exposure and lighting controls, manipulating focus and color, and transferring your images from the camera to the computer Offers advice for shooting in various common situations and explains how to post your photos online, make prints, or share them in other ways Canon EOS 70D For Dummies makes it easy to get terrific photos with your Canon dSLR camera. In one of the most brutally raw, revealing books written on substance abuse, Deanna delivers a powerful, inspirational message of hope to anyone dealing with opioid addiction. Topics covered will include: The key elements in becoming more persuasive - body language, listening skills, using persuasive words and actionsFinding a common ground and establishing a connection with your audienceCapturing their attention and keeping them interestedPutting yourself across convincinglyGetting things done through othersIdentifying the type of person you're dealing with - and responding in an appropriate manner More IQ Testing: 250 New Ways to Release Your IQ PotentialIncrease your powers of vocabulary, calculation and logical reasoning with this book of brand new IQ tests.