Introduction: a Manufacturing People

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MACHINES OR ENGINES, in GENERAL OR of POSITIVE-DISPLACEMENT TYPE, Eg STEAM ENGINES

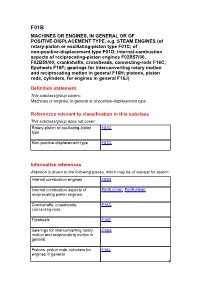

F01B MACHINES OR ENGINES, IN GENERAL OR OF POSITIVE-DISPLACEMENT TYPE, e.g. STEAM ENGINES (of rotary-piston or oscillating-piston type F01C; of non-positive-displacement type F01D; internal-combustion aspects of reciprocating-piston engines F02B57/00, F02B59/00; crankshafts, crossheads, connecting-rods F16C; flywheels F16F; gearings for interconverting rotary motion and reciprocating motion in general F16H; pistons, piston rods, cylinders, for engines in general F16J) Definition statement This subclass/group covers: Machines or engines, in general or of positive-displacement type References relevant to classification in this subclass This subclass/group does not cover: Rotary-piston or oscillating-piston F01C type Non-positive-displacement type F01D Informative references Attention is drawn to the following places, which may be of interest for search: Internal combustion engines F02B Internal combustion aspects of F02B 57/00; F02B 59/00 reciprocating piston engines Crankshafts, crossheads, F16C connecting-rods Flywheels F16F Gearings for interconverting rotary F16H motion and reciprocating motion in general Pistons, piston rods, cylinders for F16J engines in general 1 Cyclically operating valves for F01L machines or engines Lubrication of machines or engines in F01M general Steam engine plants F01K Glossary of terms In this subclass/group, the following terms (or expressions) are used with the meaning indicated: In patent documents the following abbreviations are often used: Engine a device for continuously converting fluid energy into mechanical power, Thus, this term includes, for example, steam piston engines or steam turbines, per se, or internal-combustion piston engines, but it excludes single-stroke devices. Machine a device which could equally be an engine and a pump, and not a device which is restricted to an engine or one which is restricted to a pump. -

Assessing Steam Locomotive Dynamics and Running Safety by Computer Simulation

TRANSPORT PROBLEMS 2015 PROBLEMY TRANSPORTU Volume 10 Special Edition steam locomotive; balancing; reciprocating; hammer blow; rolling stock and track interaction Dāvis BUŠS Institute of Transportation, Riga Technical University Indriķa iela 8a, Rīga, LV-1004, Latvia Corresponding author. E-mail: [email protected] ASSESSING STEAM LOCOMOTIVE DYNAMICS AND RUNNING SAFETY BY COMPUTER SIMULATION Summary. Steam locomotives are preserved on heritage railways and also occasionally used on mainline heritage trips, but since they are only partially balanced reciprocating piston engines, damage is made to the railway track by dynamic impact, also known as hammer blow. While causing a faster deterioration to the track on heritage railways, the steam locomotive may also cause deterioration to busy mainline tracks or tracks used by high speed trains. This raises the question whether heritage operations on mainline can be done safely and without influencing the operation of the railways. If the details of the dynamic interaction of the steam locomotive's components are examined with computerised calculations they show differences with the previous theories as the smaller components cannot be disregarded in some vibration modes. A particular narrow gauge steam locomotive Gr-319 was analyzed and it was found, that the locomotive exhibits large dynamic forces on the track, much larger than those given by design data, and the safety of the ride is impaired. Large unbalanced vibrations were found, affecting not only the fatigue resistance of the locomotive, but also influencing the crew and passengers in the train consist. Developed model and simulations were used to check several possible parameter variations of the locomotive, but the problems were found to be in the original design such that no serious improvements can be done in the space available for the running gear and therefore the running speed of the locomotive should be limited to reduce its impact upon the track. -

Performance and Scaling Analysis of a Hypocycloid Wiseman Engine By

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by ASU Digital Repository Performance and Scaling Analysis of a Hypocycloid Wiseman Engine by Priyesh Ray A Thesis Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Science in Technology Approved April 2014 by the Graduate Supervisory Committee: Sangram Redkar, Chair Abdel Ra'ouf Mayyas Robert Meitz ARIZONA STATE UNIVERSITY May 2014 ABSTRACT The slider-crank mechanism is popularly used in internal combustion engines to convert the reciprocating motion of the piston into a rotary motion. This research discusses an alternate mechanism proposed by the Wiseman Technology Inc. which involves replacing the crankshaft with a hypocycloid gear assembly. The unique hypocycloid gear arrangement allows the piston and the connecting rod to move in a straight line, creating a perfect sinusoidal motion. To analyze the performance advantages of the Wiseman mechanism, engine simulation software was used. The Wiseman engine with the hypocycloid piston motion was modeled in the software and the engine’s simulated output results were compared to those with a conventional engine of the same size. The software was also used to analyze the multi-fuel capabilities of the Wiseman engine using a contra piston. The engine’s performance was studied while operating on diesel, ethanol and gasoline fuel. Further, a scaling analysis on the future Wiseman engine prototypes was carried out to understand how the performance of the engine is affected by increasing the output power and cylinder displacement. It was found that the existing Wiseman engine produced about 7% less power at peak speeds compared to the slider-crank engine of the same size. -

Intellectual Property Center, 28 Upper Mckinley Rd. Mckinley Hill Town Center, Fort Bonifacio, Taguig City 1634, Philippines Tel

Intellectual Property Center, 28 Upper McKinley Rd. McKinley Hill Town Center, Fort Bonifacio, Taguig City 1634, Philippines Tel. No. 238-6300 Website: http://www.ipophil.gov.ph e-mail: [email protected] Publication Date: August 10, 2015 1 ALLOWED MARKS PUBLISHED FOR OPPOSITION ............................................................................................... 2 1.1 ALLOWED NATIONAL MARKS ....................................................................................................................................... 2 Intellectual Property Center, 28 Upper McKinley Rd. McKinley Hill Town Center, Fort Bonifacio, Taguig City 1634, Philippines Tel. No. 238-6300 Website: http://www.ipophil.gov.ph e-mail: [email protected] Publication Date: August 10, 2015 1 ALLOWED MARKS PUBLISHED FOR OPPOSITION 1.1 Allowed national marks Application No. Filing Date Mark Applicant Nice class(es) Number 25 June 1 4/2010/00006843 AIR21 GLOBAL AIR21 GLOBAL, INC. [PH] 35 and39 2010 20 2 4/2012/00011594 September AAA SUNQUAN LU [PH] 19 2012 11 May 3 4/2012/00501163 CACATIAN, LEUGIM D [PH] 25 2012 24 4 4/2012/00740257 September MIX N` MAGIC MICHAELA A TAN [PH] 30 2012 11 June NEUROGENESIS 5 4/2013/00006764 LBI BRANDS, INC. [CA] 32 2013 HAPPY WATER BABAYLAN SPA AND ALLIED 6 4/2013/00007633 1 July 2013 BABAYLAN 44 INC. [PH] 12 July OAKS HOTELS & M&H MANAGEMENT 7 4/2013/00008241 43 2013 RESORTS LIMITED [MU] 25 July DAIWA HOUSE INDUSTRY 8 4/2013/00008867 DAIWA HOUSE 36; 37 and42 2013 CO., LTD. [JP] 16 August ELLEBASY MEDICALE ELLEBASY MEDICALE 9 4/2013/00009840 35 2013 TRADING TRADING [PH] 9 THE PROCTER & GAMBLE 10 4/2013/00010788 September UNSTOPABLES 3 COMPANY [US] 2013 9 October BELL-KENZ PHARMA INC. -

![[Thesis Title Goes Here]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3925/thesis-title-goes-here-423925.webp)

[Thesis Title Goes Here]

DETAILED STUDY OF THE TRANSIENT ROD PNEUMATIC SYSTEM ON THE ANNULAR CORE RESEARCH REACTOR A Thesis Presented to The Academic Faculty by Brandon M. Fehr In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Science in Nuclear Engineering in the School of Nuclear and Radiological Engineering and Medical Physics Program, George W. Woodruff School of Mechanical Engineering Georgia Institute of Technology May 2016 COPYRIGHT © 2016 BY BRANDON M. FEHR iv DETAILED STUDY OF THE TRANSIENT ROD PNEUMATIC SYSTEM ON THE ANNULAR CORE RESEARCH REACTOR Approved by: Dr. Farzad Rahnema, Advisor Mr. Michael Black School of Nuclear and Radiological R&D S&E Mechanical Engineering Engineering Sandia National Laboratories Georgia Institute of Technology Dr. Tristan Utschig School of Nuclear and Radiological Engineering Georgia Institute of Technology Dr. Bojan Petrovic School of Nuclear and Radiological Engineering Georgia Institute of Technology Date Approved: April 11, 2016 v ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to give the utmost appreciation to my colleagues at Sandia National Laboratories for their support, with special thanks to Michael Black, James Arnold, and Paul Helmick for their technical guidance. I would also like to thank Dulce Barrera and Elliott Pelfrey for their encouragement and support, and Bennett Lee for his help with proofreading and formatting. Special thanks to Dr. Farzad Rahnema for his guidance and contract support, as well as, Dr. Bojan Petrovic and Dr. Tris Utschig for serving on my committee. Lastly, I would like to thank my parents for their support and encouragement during the whole journey. This research was funded by Weapons Science & Technology (WS&T), Readiness in Technical Base and Facilities (RTBF). -

Soho Depicted: Prints, Drawings and Watercolours of Matthew Boulton, His Manufactory and Estate, 1760-1809

SOHO DEPICTED: PRINTS, DRAWINGS AND WATERCOLOURS OF MATTHEW BOULTON, HIS MANUFACTORY AND ESTATE, 1760-1809 by VALERIE ANN LOGGIE A thesis submitted to The University of Birmingham for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Department of History of Art College of Arts and Law The University of Birmingham January 2011 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. ABSTRACT This thesis explores the ways in which the industrialist Matthew Boulton (1728-1809) used images of his manufactory and of himself to help develop what would now be considered a ‘brand’. The argument draws heavily on archival research into the commissioning process, authorship and reception of these depictions. Such information is rarely available when studying prints and allows consideration of these images in a new light but also contributes to a wider debate on British eighteenth-century print culture. The first chapter argues that Boulton used images to convey messages about the output of his businesses, to draw together a diverse range of products and associate them with one site. Chapter two explores the setting of the manufactory and the surrounding estate, outlining Boulton’s motivation for creating the parkland and considering the ways in which it was depicted. -

LIVES of the ENGINEERS. the LOCOMOTIVE

LIVES of the ENGINEERS. THE LOCOMOTIVE. GEORGE AND ROBERT STEPHENSON. BY SAMUEL SMILES, INTRODUCTION. Since the appearance of this book in its original form, some seventeen years since, the construction of Railways has continued to make extraordinary progress. Although Great Britain, first in the field, had then, after about twenty-five years‘ work, expended nearly 300 millions sterling in the construction of 8300 miles of railway, it has, during the last seventeen years, expended about 288 millions more in constructing 7780 additional miles. But the construction of railways has proceeded with equal rapidity on the Continent. France, Germany, Spain, Sweden, Belgium, Switzerland, Holland, have largely added to their railway mileage. Austria is actively engaged in carrying new lines across the plains of Hungary, which Turkey is preparing to meet by lines carried up the valley of the Lower Danube. Russia is also occupied with extensive schemes for connecting Petersburg and Moscow with her ports in the Black Sea on the one hand, and with the frontier towns of her Asiatic empire on the other. Italy is employing her new-born liberty in vigorously extending railways throughout her dominions. A direct line of communication has already been opened between France and Italy, through the Mont Cenis Tunnel; while p. ivanother has been opened between Germany and Italy through the Brenner Pass,—so that the entire journey may now be made by two different railway routes excepting only the short sea-passage across the English Channel from London to Brindisi, situated in the south-eastern extremity of the Italian peninsula. During the last sixteen years, nearly the whole of the Indian railways have been made. -

THE ASSOCIATION for INDUSTRIAL ARCHAEOLOGY F 1.25 FREE to MEMBERS of AIA

INDUSTRIAL ARCHAEOLOGY THE BULLETIN OF THE ASSOCIATION FOR INDUSTRIAL ARCHAEOLOGY f 1.25 FREE TO MEMBERS OF AIA Polish feature * s*,lrirr,*i''e AIA lronbridge Award o Marconi centenary o Bull engine oldest beam engrile house o coalfield housing o World Heritage Site c Bovisa Current Research and Thinking in Industrial Archaeology: The Pre- Conference Seminar at Manchester 20OO INDUSTRIAL The AIA's traditional pre-conference seminar was shaoed a site.Surface remains can be a reflection of held on 8 September 2000 in the hallowed underground working methods and can therefore be ARCHAEOLOGY surroundings of the chapel at Hulme Hall, which the key to understanding how and why a site was NEWS 116 worked well until the sun came out. since there worked: they can equally be very misleading. Ihis was no black-out! The organisers apologise for paper asserted that it is necessary in studying the 20()1 this defect to both speakers and delegates at archaeology of mining to consider carefully the what was otherwise an extremelv successful symbiotic relationship that exists between the Chairman gathering. surface and the underground remains. Dr Michael Harrison John Walker (Greater Manchester I 9 Sandles Close, the Ridings, Droitwich Spa, WR9 8RB Marilyn Palmer and Peter Neaverson Archaeological Unit), also, with Michael Nevell, a Vice-Chairman winner of the AIA Fieldwork and Recording Award, Prof Marilyn Palmer took as his title 'From farmer to factory owner: a School of Archaeological Studies, The University, Our first contributor was Tim Smith (Greater Leicester LEl 7RH model of industrialisation from the Manchester London Industrial Archaeology Society) on evidence', In Tameside in Transition, they took the Secretary the weight-loaded hydraulic accumulator and new monument types established for the period David Alderton accumulator towers, on which Tim is the 48 Quay Street, Halesworth, Suffolk lP1 9 8EY 1600-1 900 which were included the undoubted authority. -

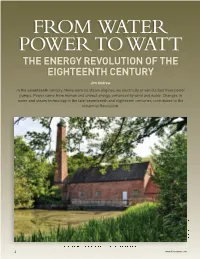

A Steam Issue-48Pp HWM

FROM WATER POWER TO WATT THE ENERGY REVOLUTION OF THE EIGHTEENTH CENTURY Jim Andrew In the seventeenth century, there were no steam engines, no electricity or vehicle fuel from petrol pumps. Power came from human and animal energy, enhanced by wind and water. Changes in water and steam technology in the late-seventeenth and eighteenth centuries contributed to the Industrial Revolution. © Birmingham Museums Trust Sarehole Mill. One of the two remaining water mills in the Birmingham area. 4 www.historywm.com FROM WATER POWER TO WATT ind power, as now, was limited by variations in the strength of the wind, making water the preferred reliable Wsource of significant power for regular activity. The Romans developed water wheels and used them for a variety of activities but the first definitive survey of water power in England was in the Doomsday Book c.1086. At that time, well over five-thousand mills were identified – most were the Norse design with a vertical shaft and horizontal disc of blades. Water-Wheel Technology Traditional water mills, with vertical wheels on horizontal shafts, were well established by the eighteenth century. Many were underpass designs where the water flowed under a wheel with paddles being pushed round by the flow. Over time, many mills adopted designs which had buckets, filled with water at various levels from quite low to the very top of the wheel. The power was extracted by the falling of the water from its entry point to where it was discharged. There was little systematic study of the efficiency of mill-wheel design in extracting energy from the water before the eighteenth century. -

The Evolution of the Steam Locomotive, 1803 to 1898 (1899)

> g s J> ° "^ Q as : F7 lA-dh-**^) THE EVOLUTION OF THE STEAM LOCOMOTIVE (1803 to 1898.) BY Q. A. SEKON, Editor of the "Railway Magazine" and "Hallway Year Book, Author of "A History of the Great Western Railway," *•., 4*. SECOND EDITION (Enlarged). £on&on THE RAILWAY PUBLISHING CO., Ltd., 79 and 80, Temple Chambers, Temple Avenue, E.C. 1899. T3 in PKEFACE TO SECOND EDITION. When, ten days ago, the first copy of the " Evolution of the Steam Locomotive" was ready for sale, I did not expect to be called upon to write a preface for a new edition before 240 hours had expired. The author cannot but be gratified to know that the whole of the extremely large first edition was exhausted practically upon publication, and since many would-be readers are still unsupplied, the demand for another edition is pressing. Under these circumstances but slight modifications have been made in the original text, although additional particulars and illustrations have been inserted in the new edition. The new matter relates to the locomotives of the North Staffordshire, London., Tilbury, and Southend, Great Western, and London and North Western Railways. I sincerely thank the many correspondents who, in the few days that have elapsed since the publication: of the "Evolution of the , Steam Locomotive," have so readily assured me of - their hearty appreciation of the book. rj .;! G. A. SEKON. -! January, 1899. PREFACE TO FIRST EDITION. In connection with the marvellous growth of our railway system there is nothing of so paramount importance and interest as the evolution of the locomotive steam engine. -

RT Rondelle PDF Specimen

RAZZIATYPE RT Rondelle RAZZIATYPE RT RONDELLE FAMILY Thin Rondelle Thin Italic Rondelle Extralight Rondelle Extralight Italic Rondelle Light Rondelle Light Italic Rondelle Book Rondelle Book Italic Rondelle Regular Rondelle Regular Italic Rondelle Medium Rondelle Medium Italic Rondelle Bold Rondelle Bold Italic Rondelle Black Rondelle Black Italic Rondelle RAZZIATYPE TYPEFACE INFORMATION About RT Rondelle is the result of an exploration into public transport signage typefa- ces. While building on this foundation it incorporates the distinctive characteri- stics of a highly specialized genre to become a versatile grotesque family with a balanced geometrical touch. RT Rondelle embarks on a new life of its own, lea- ving behind the restrictions of its heritage to form a consistent and independent type family. Suited for a wide range of applications www.rt-rondelle.com Supported languages Afrikaans, Albanian, Basque, Bosnian, Breton, Catalan, Croatian, Czech, Danish, Dutch, English, Esperanto, Estonian, Faroese, Fijian, Finnish, Flemish, French, Frisian, German, Greenlandic, Hawaiian, Hungarian, Icelandic, Indonesian, Irish, Italian, Latin, Latvian, Lithuanian, Malay, Maltese, Maori, Moldavian, Norwegian, Polish, Portuguese, Provençal, Romanian, Romany, Sámi (Inari), Sámi (Luli), Sámi (Northern), Sámi (Southern), Samoan, Scottish Gaelic, Slovak, Slovenian, Sorbian, Spa- nish, Swahili, Swedish, Tagalog, Turkish, Welsh File formats Desktop: OTF Web: WOFF2, WOFF App: OTF Available licenses Desktop license Web license App license Further licensing -

I Lecture Note

Machine Dynamics – I Lecture Note By Er. Debasish Tripathy ( Assist. Prof. Mechanical Engineering Department, VSSUT, Burla, Orissa,India) Syllabus: Module – I 1. Mechanisms: Basic Kinematic concepts & definitions, mechanisms, link, kinematic pair, degrees of freedom, kinematic chain, degrees of freedom for plane mechanism, Gruebler’s equation, inversion of mechanism, four bar chain & their inversions, single slider crank chain, double slider crank chain & their inversion.(8) Module – II 2. Kinematics analysis: Determination of velocity using graphical and analytical techniques, instantaneous center method, relative velocity method, Kennedy theorem, velocity in four bar mechanism, slider crank mechanism, acceleration diagram for a slider crank mechanism, Klein’s construction method, rubbing velocity at pin joint, coriolli’s component of acceleration & it’s applications. (12) Module – III 3. Inertia force in reciprocating parts: Velocity & acceleration of connecting rod by analytical method, piston effort, force acting along connecting rod, crank effort, turning moment on crank shaft, dynamically equivalent system, compound pendulum, correction couple, friction, pivot & collar friction, friction circle, friction axis. (6) 4. Friction clutches: Transmission of power by single plate, multiple & cone clutches, belt drive, initial tension, Effect of centrifugal tension on power transmission, maximum power transmission(4). Module – IV 5. Brakes & Dynamometers: Classification of brakes, analysis of simple block, band & internal expanding shoe brakes, braking of a vehicle, absorbing & transmission dynamometers, prony brakes, rope brakes, band brake dynamometer, belt transmission dynamometer & torsion dynamometer.(7) 6. Gear trains: Simple trains, compound trains, reverted train & epicyclic train. (3) Text Book: Theory of machines, by S.S Ratan, THM Mechanism and Machines Mechanism: If a number of bodies are assembled in such a way that the motion of one causes constrained and predictable motion to the others, it is known as a mechanism.