INDUSTRIAL REVOLUTION: SERIES ONE: the Boulton and Watt Archive, Parts 2 and 3

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MACHINES OR ENGINES, in GENERAL OR of POSITIVE-DISPLACEMENT TYPE, Eg STEAM ENGINES

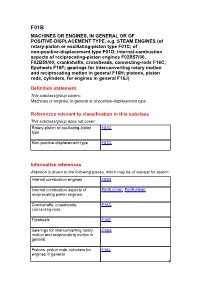

F01B MACHINES OR ENGINES, IN GENERAL OR OF POSITIVE-DISPLACEMENT TYPE, e.g. STEAM ENGINES (of rotary-piston or oscillating-piston type F01C; of non-positive-displacement type F01D; internal-combustion aspects of reciprocating-piston engines F02B57/00, F02B59/00; crankshafts, crossheads, connecting-rods F16C; flywheels F16F; gearings for interconverting rotary motion and reciprocating motion in general F16H; pistons, piston rods, cylinders, for engines in general F16J) Definition statement This subclass/group covers: Machines or engines, in general or of positive-displacement type References relevant to classification in this subclass This subclass/group does not cover: Rotary-piston or oscillating-piston F01C type Non-positive-displacement type F01D Informative references Attention is drawn to the following places, which may be of interest for search: Internal combustion engines F02B Internal combustion aspects of F02B 57/00; F02B 59/00 reciprocating piston engines Crankshafts, crossheads, F16C connecting-rods Flywheels F16F Gearings for interconverting rotary F16H motion and reciprocating motion in general Pistons, piston rods, cylinders for F16J engines in general 1 Cyclically operating valves for F01L machines or engines Lubrication of machines or engines in F01M general Steam engine plants F01K Glossary of terms In this subclass/group, the following terms (or expressions) are used with the meaning indicated: In patent documents the following abbreviations are often used: Engine a device for continuously converting fluid energy into mechanical power, Thus, this term includes, for example, steam piston engines or steam turbines, per se, or internal-combustion piston engines, but it excludes single-stroke devices. Machine a device which could equally be an engine and a pump, and not a device which is restricted to an engine or one which is restricted to a pump. -

Mechanical Design and Analysis of a Discrete Variable Transmission System for Transmission-Based Actuators

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Masters Theses Graduate School 5-2004 Mechanical Design and Analysis of a Discrete Variable Transmission System for Transmission-Based Actuators Sriram Sridharan University of Tennessee - Knoxville Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes Part of the Mechanical Engineering Commons Recommended Citation Sridharan, Sriram, "Mechanical Design and Analysis of a Discrete Variable Transmission System for Transmission-Based Actuators. " Master's Thesis, University of Tennessee, 2004. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes/2205 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a thesis written by Sriram Sridharan entitled "Mechanical Design and Analysis of a Discrete Variable Transmission System for Transmission-Based Actuators." I have examined the final electronic copy of this thesis for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree of Master of Science, with a major in Mechanical Engineering. Arnold Lumsdaine, Major Professor We have read this thesis and recommend its acceptance: William R. Hamel, Frank H. Speckhart Accepted for the Council: Carolyn -

The Smelting of Copper

Chapter 4 The Smelting of Copper The first written account of the processes of smelting and refining of copper is to be found in the 12th century.1 On smelting: Copper is engendered in the earth. When a vein of which is found, it is acquired with the greatest labour by digging and breaking. It is a stone of a green colour and most hard, and naturally mixed with lead. This stone, dug up in abundance, is placed upon a pile, and burned after the manner of chalk, nor does it change colour, but yet looses its hardness, so that it can be broken up. Then, being bruised small, it is placed in the furnace; coals and the bellows being applied, it is incessantly forged by day and night. On refining: Of the purification of copper. Take an iron dish of the size you wish, and line it inside and and out with clay strongly beaten and mixed, and it is carefully dried. Then place it before a forge upon the coals, so that when the bellows acts upon it the wind may issue partly within and partly above it, and not below it. And very small coals being placed around it equally, and add over it a heap of coals. When, by blowing a long time, this has become melted, uncover it and cast immediately fine ashes over it, and stir it with a thin and dry piece of wood as if mixing it, and you will directly see the burnt lead adhere to these ashes like a glue. -

Positive Displacement Reciprocating Pump Fundamentals— Power and Direct Acting Types

POSITIVE DISPLACEMENT RECIPROCATING PUMP FUNDAMENTALS— POWER AND DIRECT ACTING TYPES by Herbert H. Tackett, Jr. Reciprocating Product Manager James A. Cripe Senior Reciprocating Product Engineer Union Pump Company; A Textron Company Battle Creek, Michigan and Gary Dyson Director of Product Development - Aftermarket Union Pump, A Textron Company A Trading Division of David Brown Engineering, Limited Penistone, Sheffield ABSTRACT Herbert H. Tackett, Jr., is Reciprocating Product Manager for Union Pump Company, This tutorial is intended to provide an understanding of the in Battle Creek, Michigan. He has 39 years fundamental principles of positive displacement reciprocating of experience in the design, application, and pumps of both power and direct acting types. Topics include: maintenance of reciprocating power and • A definition and overview of the pump types—Including the direct acting pumps. Prior to Mr. Tackett’s differences between single acting and double acting pumps, how current position in Aftermarket Product both types work, where they are used, and how they are applied. Development, he served as R&D Engineer, Field Service Engineer, and new equipment • Component options—Covers aspects of valve designs and when order Engineer, in addition to several they should be used; describes the various stuffing box designs positions in Reciprocating Pump Sales and Marketing. He has been available with specific reference to their function and application, a member of ASME since 1991. and points out the differences between plungers and pistons and their selection criteria. • Specification criteria and methodology—What application James A. Cripe currently is a Senior information is needed by pump suppliers to correctly size and Reciprocating Product Engineer assigned supply appropriate equipment? to the New Product Development Team for Union Pump Company, in Battle Creek, • Additional topics—Volumetric and mechanical efficiency, net Michigan. -

Reciprocating Pump

Mechanical Engineering Fundamentals Vipan Bansal Department of Mechanical Engineering ([email protected]) Mechanical Engineering Fundamentals (MEC103) L T P Cr 4 0 0 4 Content 1) Fundamental Concepts of Thermodynamics 2) Laws of Thermodynamics 3) Pressure and its Measurement 4) Heat Transfer 5) Power Absorbing Devices 6) Power Producing Devices 7) Principles of Design 8) Power Transmission Devices and Machine Elements Lecture No. - 2 • Positive displacement Pumps Power Absorbing Devices The equipment's or devices that consume power for the working are called power absorbing devices. Examples: Pumps, Compressor, Refrigerators etc. Classification of Pumps Type of Pumps Positive Dynamic Displacement Reciprocating Rotary Centrifugal Axial Positive Displacement vs Dynamic Pumps S. No. Parameter Positive Displacement Pumps Dynamic Pumps 1 Flow Rate Low flow rate High flow rate 2 Pressure High Moderate 3 Priming Very Rarely Always 4 Viscosity Virtually No effect Strong effect 5 Energy added to In positive displacement pumps, In dynamic pumps, energy is added to fluid the energy is added periodically to the fluid continuously through the the fluid. rotary motion of the blades. Reciprocating Pump • Reciprocating pumps are positive displacement pumps thus for the functioning of these pumps no priming (No need to fill the cylinder with liquid before starting) is required in their starting. • High pressure is the main characters of this pump. Reciprocating Pump • In reciprocating pumps, the chamber in which the liquid is trapped or entered, is a stationary cylinder that contains piston or plunger or diaphragm. • Reciprocating pumps are used in limited applications because they require lots of maintenance. • Piston pump, plunger pumps, and diaphragm pumps are examples of reciprocating pump. -

Intellectual Property Center, 28 Upper Mckinley Rd. Mckinley Hill Town Center, Fort Bonifacio, Taguig City 1634, Philippines Tel

Intellectual Property Center, 28 Upper McKinley Rd. McKinley Hill Town Center, Fort Bonifacio, Taguig City 1634, Philippines Tel. No. 238-6300 Website: http://www.ipophil.gov.ph e-mail: [email protected] Publication Date: August 10, 2015 1 ALLOWED MARKS PUBLISHED FOR OPPOSITION ............................................................................................... 2 1.1 ALLOWED NATIONAL MARKS ....................................................................................................................................... 2 Intellectual Property Center, 28 Upper McKinley Rd. McKinley Hill Town Center, Fort Bonifacio, Taguig City 1634, Philippines Tel. No. 238-6300 Website: http://www.ipophil.gov.ph e-mail: [email protected] Publication Date: August 10, 2015 1 ALLOWED MARKS PUBLISHED FOR OPPOSITION 1.1 Allowed national marks Application No. Filing Date Mark Applicant Nice class(es) Number 25 June 1 4/2010/00006843 AIR21 GLOBAL AIR21 GLOBAL, INC. [PH] 35 and39 2010 20 2 4/2012/00011594 September AAA SUNQUAN LU [PH] 19 2012 11 May 3 4/2012/00501163 CACATIAN, LEUGIM D [PH] 25 2012 24 4 4/2012/00740257 September MIX N` MAGIC MICHAELA A TAN [PH] 30 2012 11 June NEUROGENESIS 5 4/2013/00006764 LBI BRANDS, INC. [CA] 32 2013 HAPPY WATER BABAYLAN SPA AND ALLIED 6 4/2013/00007633 1 July 2013 BABAYLAN 44 INC. [PH] 12 July OAKS HOTELS & M&H MANAGEMENT 7 4/2013/00008241 43 2013 RESORTS LIMITED [MU] 25 July DAIWA HOUSE INDUSTRY 8 4/2013/00008867 DAIWA HOUSE 36; 37 and42 2013 CO., LTD. [JP] 16 August ELLEBASY MEDICALE ELLEBASY MEDICALE 9 4/2013/00009840 35 2013 TRADING TRADING [PH] 9 THE PROCTER & GAMBLE 10 4/2013/00010788 September UNSTOPABLES 3 COMPANY [US] 2013 9 October BELL-KENZ PHARMA INC. -

6 X 10 Long Title.P65

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-15382-9 - Heroes of Invention: Technology, Liberalism and British Identity, 1750-1914 Christine MacLeod Index More information Index Acade´mie des Sciences 80, 122, 357 arms manufacturers 236–9 Adam, Robert 346 Armstrong, William, Baron Armstrong of Adams, John Couch 369 Cragside Aikin, John 43, 44, 71 arms manufacturer 220 Airy, Sir George 188, 360 as hero of industry 332 Albert, Prince 24, 216, 217, 231, 232, 260 concepts of invention 268, 269, 270 Alfred, King 24 entrepreneurial abilities of 328 Amalgamated Society of Engineers, knighted 237–8 Machinists, Millwrights, Smiths and monument to 237 Pattern Makers 286–7 opposition to patent system 250, 267–8 ancestor worship, see idolatry portrait of 230 Anderson’s Institution, Glasgow 113, 114, president of BAAS 355 288, 289 Punch’s ‘Lord Bomb’ 224–5 Arago, Franc¸ois 122, 148, 184 Ashton, T. S. 143 Eloge, to James Watt 122–3, 127 Athenaeum, The 99–101, 369 Arkwright, Sir Richard, Atkinson, T. L. 201 and scientific training 359 Atlantic telegraph cables 243, 245, 327 as national benefactor 282 Arthur, King 15 as workers’ hero 286 Askrill, Robert 213 commemorations of, 259 Associated Society of Locomotive Cromford mills, painting of 63 Engineers and Firemen 288 enterprise of 196, 327, 329 era of 144 Babbage, Charles 276, 353, 356–7, factory system 179 375, 383 in Erasmus Darwin’s poetry 67–8 Bacon, Sir Francis in Maria Edgeworth’s book 171 as discoverer 196 in Samuel Smiles’ books 255, 256 as genius 51, 53, 142 invention of textile machinery 174, 176 bust of 349 knighthood 65 n. -

Soho Depicted: Prints, Drawings and Watercolours of Matthew Boulton, His Manufactory and Estate, 1760-1809

SOHO DEPICTED: PRINTS, DRAWINGS AND WATERCOLOURS OF MATTHEW BOULTON, HIS MANUFACTORY AND ESTATE, 1760-1809 by VALERIE ANN LOGGIE A thesis submitted to The University of Birmingham for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Department of History of Art College of Arts and Law The University of Birmingham January 2011 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. ABSTRACT This thesis explores the ways in which the industrialist Matthew Boulton (1728-1809) used images of his manufactory and of himself to help develop what would now be considered a ‘brand’. The argument draws heavily on archival research into the commissioning process, authorship and reception of these depictions. Such information is rarely available when studying prints and allows consideration of these images in a new light but also contributes to a wider debate on British eighteenth-century print culture. The first chapter argues that Boulton used images to convey messages about the output of his businesses, to draw together a diverse range of products and associate them with one site. Chapter two explores the setting of the manufactory and the surrounding estate, outlining Boulton’s motivation for creating the parkland and considering the ways in which it was depicted. -

Jabez Carter Hornblower 07 27 2009

Jabez Carter Hornblower 1744-1814 Jabez Carter Hornblower, Engineer and Inventor (1744-1814) © 2009 Susan W. Howard Penrosefam.org July 27, 2009 Chapter 1 “Jabez” is a biblical name meaning sorrow or trouble. For the firstborn child of Jonathan and Ann Hornblower the name was indeed prophetic; troubles plagued him throughout his life. His middle name, Carter, came from his mother’s family. Although he was the only Hornblower child given a middle name, he was often confused with a younger brother, Jonathan Junior, who is often called Jonathan Carter Hornblower. This confusion persists today in a number of books and an occasional scholarly article.1 If we look only at the low points of the life of Jabez Carter Hornblower, we might wonder how he kept going through seventy years of losses and failures. Yet, he had an amazing resiliency and recovered from depressing circumstances including bankruptcy and debtor’s prison. Despite negative judgments on his character, Jabez had many good qualities. Fortunately his daughter Annetta Hornblower Hillhouse wrote a brief biography of this intriguing figure. His nephew, journalist and writer of memoirs Cyrus Redding, added to the story. Jabez wrote many letters that have survived; yet not all of these have not been studied in relation to his life story. Ann Carter Hornblower gave birth to her first child, Jabez, on 21 May 1744 in Staffordshire, England. He was christened on 10 December 1744, at St. Leonard, Broseley, Shropshire, where Ann’s family lived. Jonathan Hornblower’s parents, Joseph and Rebecca, were members of a closely-knit circle of Baptist friends of Thomas Newcomen, inventor of the atmospheric steam engine. -

A Steam Issue-48Pp HWM

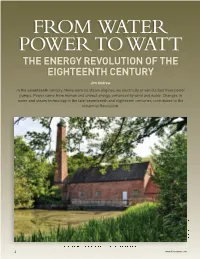

FROM WATER POWER TO WATT THE ENERGY REVOLUTION OF THE EIGHTEENTH CENTURY Jim Andrew In the seventeenth century, there were no steam engines, no electricity or vehicle fuel from petrol pumps. Power came from human and animal energy, enhanced by wind and water. Changes in water and steam technology in the late-seventeenth and eighteenth centuries contributed to the Industrial Revolution. © Birmingham Museums Trust Sarehole Mill. One of the two remaining water mills in the Birmingham area. 4 www.historywm.com FROM WATER POWER TO WATT ind power, as now, was limited by variations in the strength of the wind, making water the preferred reliable Wsource of significant power for regular activity. The Romans developed water wheels and used them for a variety of activities but the first definitive survey of water power in England was in the Doomsday Book c.1086. At that time, well over five-thousand mills were identified – most were the Norse design with a vertical shaft and horizontal disc of blades. Water-Wheel Technology Traditional water mills, with vertical wheels on horizontal shafts, were well established by the eighteenth century. Many were underpass designs where the water flowed under a wheel with paddles being pushed round by the flow. Over time, many mills adopted designs which had buckets, filled with water at various levels from quite low to the very top of the wheel. The power was extracted by the falling of the water from its entry point to where it was discharged. There was little systematic study of the efficiency of mill-wheel design in extracting energy from the water before the eighteenth century. -

Prices and Profits in Cotton Textiles During the Industrial Revolution C

PRICES AND PROFITS IN COTTON TEXTILES DURING THE INDUSTRIAL REVOLUTION C. Knick Harley PRICES AND PROFITS IN COTTON TEXTILES DURING THE 1 INDUSTRIAL REVOLUTION C. Knick Harley Department of Economics and St. Antony’s College University of Oxford Oxford OX2 6JF UK <[email protected]> Abstract Cotton textile firms led the development of machinery-based industrialization in the Industrial Revolution. This paper presents price and profits data extracted from the accounting records of three cotton firms between the 1770s and the 1820s. The course of prices and profits in cotton textiles illumine the nature of the economic processes at work. Some historians have seen the Industrial Revolution as a Schumpeterian process in which discontinuous technological change created large profits for innovators and succeeding decades were characterized by slow diffusion. Technological secrecy and imperfect capital markets limited expansion of use of the new technology and output expanded as profits were reinvested until eventually the new technology dominated. The evidence here supports a more equilibrium view which the industry expanded rapidly and prices fell in response to technological change. Price and profit evidence indicates that expansion of the industry had led to dramatic price declines by the 1780s and there is no evidence of super profits thereafter. Keywords: Industrial Revolution, cotton textiles, prices, profits. JEL Classification Codes: N63, N83 1 I would like to thank Christine Bies provided able research assistance, participants in the session on cotton textiles for the XII Congress of the International Economic Conference in Madrid, seminars at Cambridge and Oxford and Dr Tim Leung for useful comments. -

Matthew Boutlon and Francis Eginton's Mechanical

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by University of Birmingham Research Archive, E-theses Repository MATTHEW BOULTON AND FRANCIS EGINTON’S MECHANICAL PAINTINGS: PRODUCTION AND CONSUMPTION 1777 TO 1781 by BARBARA FOGARTY A thesis submitted to The University of Birmingham For the degree of MASTER OF PHILOSOPHY Department of History of Art College of Arts and Law The University of Birmingham June 2010 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. ABSTRACT The mechanical paintings of Matthew Boulton and Francis Eginton have been the subject of few scholarly publications since their invention in the 1770s. Such interest as there has been has focussed on the unknown process, and the lack of scientific material analysis has resulted in several confusing theories of production. This thesis’s use of the Archives of Soho, containing Boulton’s business papers, has cast light on the production and consumption of mechanical paintings, while collaboration with the British Museum, and their new scientific evidence, have both supported and challenged the archival evidence. This thesis seeks to prove various propositions about authenticity, the role of class and taste in the selection of artists and subjects for mechanical painting reproduction, and the role played by the reproductive process’s ingenuity in marketing the finished product.