Author: Ali JAMSHED Matriculation No. 2846835 Submission Date: 05

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Flood Emergency Reconstruction and Resilience Project, Loan No

Social Due Diligence Report Document stage: Final Date: 23 October 2016 PAK: Flood Emergency Reconstruction and Resilience Project, Loan No. 3264 Social Due Diligence Report of Left Marginal Bund (LMB) of Qadirabad Headwords. Reviewed by: Abdul Hameed, TA Resettlement Specialist for Project Implementation Unit, Punjab Irrigation Department (PID), Government of Punjab, Lahore. This due diligence report is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB's Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. Due Diligence Report of Left Marginal Bund, Qadirabad Flood Emergency Reconstruction and Resilience Project GOVERNMENT OF THE PUNJAB Loan 3264: PAK - FLOOD EMERGENCY RECONSTRUCTION AND RESILIENCE PROJECT (FERRP) DUE DILIGENCE REPORT OF LEFT MARGINAL BUND OF Qadirabad HEADWORKS October 2016 Prepared by: Project Implementation Unit, Punjab Irrigation Department (PID), Lahore 2 Due Diligence Report of Left Marginal Bund, Qadirabad Flood Emergency Reconstruction and Resilience Project TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER 1 Abbreviations I. INTRODUCTION 5-7 Background 5-5 Flood Emergency Reconstruction and Resilience Project (FERRP) 5-5 Irrigation Component 5-5 Qadirabad Head works Left Marginal Bund (LMB) 5-5 Scope of Work 5-5 Project Design and Design Cross-section 6-8 CHAPTER 2 II. DUE DILIGENCE REVIEW 9-10 Purpose of DDR 9-9 Methodology 9-9 Desk Review of Project Documents 9-9 Consultations with ADB, PIU and Consultant 9-9 Field Visits 9-9 Community Consultations 9-9 Key Findings 9-9 LAR Impacts and Project Categorization 9-9 LAR and IPs Impacts 9-9 Socioeconomic and Impact Assessment Survey and Community Consultations 10-10 Institutions and Roles and Responsibilities 10-10 Grievance Redress Mechanism 10-10 Project Selection Criterion 10-10 Unanticipated Impacts 10-10 CHAPTER 3 III. -

2015 " 35Th PAKISTAN CONGRESS of ZOOLOGY (INTERNATIONAL) CENTRE OF

PROCEEDINGS OF PAKISTAN CONGRESS OF ZOOLOGY Volume 35, 2015 All the papers in this Proceedings were refereed by experts in respective disciplines THIRTY FOURTH PAKISTAN CONGRESS OF ZOOLOGY held under auspices of THE ZOOLOGICAL SOCIETY OF PAKISTAN at CENTRE OF EXCELLENCE IN MARINE BIOLOGY, UNIVERSITY OF KARACHI, KARACHI MARCH 1 – 4, 2015 CONTENTS Acknowledgements i Programme ii Members of the Congress xi Citations Life Time Achievement Award 2015 Late Prof. Dr. Shahzad A. Mufti ............................................xv Dr. Quddusi B. Kazmi .........................................................xvii Dr. Muhammad Ramzan Mirza.............................................xix Abdul Aziz Khan...................................................................xx Zoologist of the year award 2015............................................... xxii Prof. Dr. A.R. Shakoori Gold Medal 2015 ............................... xxiii Prof. Dr. Mirza Azhar Beg Gold Medal 2015 ........................... xxiv Prof. Imtiaz Ahmad Gold Medal 2015 ........................................xxv Prof. Dr. Nasima M. Tirmizi Memorial Gold Medal 2015..........xxvi Gold Medals for M.Sc. and Ph.D. positions 2015 ................... xxviii Certificate of Appreciation .........................................................xxx Research papers SAMI, A.J. JABBAR, B., AHMAD, N., NAZIR, M.T. AND SHAKOORI, A.R. in silico analysis of structure-function relationship of a neutral lipase from Tribolium castaneum .......................... 1 KHAN, I., HUSSAIN, A., KHAN, A. AND -

Of Indus River at Darband

RESTRICTED For official use only Not for . UNN42 Vol. 6 Public Disclosure Authorized REPORT TO THE PRESIDENT OF THF, INTERNATIONAL BANK FOR RECONSTRUCTION AND DEVELOPMENT AS ADMINISTRATOR OF THE INDUS BASIN DEVELOPMENT FUND STUDY OF THIE WATER AND POWER RESOURCES OF WEST PAKISI AN Public Disclosure Authorized VOLUME III Program for the Development of Surface Water Storage Public Disclosure Authorized Prepared by a Group of the World Barnk Staff Headed by Dr. P. Lieftinck July 28, 1967 Public Disclosure Authorized i R0C FPU-F ClJRRENCY EQUIVALENTS 4.76 rupees = U.S. $1.00 1 rupee = U.S. $0. 21 1 millior rupees = U. S. $210, 000 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page No. I, INTRODUCTION 11..........- II-.. SURFACE. WATER HYDROLOGY. .3 .. .. , 3 Meteorological and GeographicalI Factors, .................... 3 Discharge- Measurement and River. F-lows- ... ....... .. ,44... Sediment-.Movement ..... v...............8....... 8. Floods-.JO,:,. ,10: III.. HISTORICAL. USE OF SURFACE WATER, . 12 Development of- the. System ....... ... 12 IV.. THE IACA APPROACH ..... 17 Method- of Analysis. ........... v.. 17 Surface. Water Re.quirements;. ........ r19. Integration, of.Surface and Groundwater Supplies' .. 22 Storable. Water. 23 Balancng- of Irrigation and Power..-Requi:rements.. 25 Future. River Regime ... .. 27 Accuracy- of Basic. Data . ....................... , ,,.. 27 Vt., IDENTIFICATION OF DAM'SITES AND, COMPARISON OF. PROJECTS' 29: S'cope of-the Studies ... 29. A. The Valley of the Indus,.......... 31 Suitability of the- Valley, for: Reservoir' Storagel 31 A(l.) The Middle Indus-. ...........-.. 31 Tarbela.Projject- . .. 32 Side Valley- ProjS'ectsi Associatedt w-ith Tar.bela ... 36 The Gariala' Site......... 36 The. Dhok Pathan S.te . ... ... 39 The Sanjwal-Akhori S'ites -.- , ... 40- The Attock Site . -

World Bank Document

477~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~:. ~~~~~~44 .. Public Disclosure Authorized 00o4 Vf4. Xj a I%ARTIL i! f 4-4 .=44 !ffiS96-- * +<6 @ -*s ¢ r J t X I.S _ Public Disclosure Authorized $ 4~~~~4 S 444.44. -; K.ON- Public Disclosure Authorized .4 C'~~~~~~- 4 .,< drS nvftat' S -. 4• -"4--pt ~~~~~~~~~~~~>44z AP -r 4 ~~~~~~~~~~~~~~- -4t L~~*esPakt(tn) Lt . < - : -~ .4: . - :d'44fes-r-m t.4 Public Disclosure Authorized &~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~-Bmi & ater OIsos t TABLE OF CONTENTS c GRAZI-BAROTHA HYDROPOWER PROJECT REPORT ON SUPPLEMENTARY ENVIRONMENTAL STUDIES TABLE OF CONTENTS Page CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION 1.1 GENERAL 1.1 1.2 GENERAL DESCRIPTION OF THE PROJECT 1.1 1.3 PREVIOUS ENVIRONMENTAL STUDIES 1.2 1.4 CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS OF THE ENVIRONMENTAL REVIEW PANEL 1.2 1.5 SUPPLEMENTARY ENVIRONMENTAL STUDIES 1.3 1.6 APPENDICES 1.4 REFERENCES CHAPTER 2 ECOLOGICAL ASPECTS OF THE INDUS RIVER FLOOD PLAIN 2.1 INTRODUCTION 2.1 2.2 APPROACH 2.1 2.3 MORPHOLOGICAL AND ECOLOGICAL SETTING OF THE RIVERAIN AREA 2.2 2.4 PLANT COMMUNITIES IN VARIOUS HABITATS 2.3 2.4.1 General 2.3 2.4.2 Braided Alluvial Channel 2.3 2.4.3 Attock Gorge 2.5 2.4.4 Alluvial Basin 2.6 2.5 WILDLIFE USE OF HABITATS 2.6 2.5.1 Open Water 2.6 2.5.2 Temporary Belas 2.6 2.5.3 Permanent Belas 2.7 2.5.4 Ind-ds Gorge 2.8 2.6 POTENTIAL EFFECTS OF THE PROJECT 2.8 2.6.1 Effects on Natural Vegetation 2.8 2.6.2 Effects on Wildlife 2.10 (i) Page 2.7 CONCLUSION 2.11 REFERENCES CHAPTER 3 WASTEWATER DISPOSAL AND WATER QUALITY 3.1 INTRODUCTION 3.1 3.1.1 Background 3.1 3.1.2 -

FLOOD RISK ASSESSMENT REPORT a Hi-Tech Knowledge Management Tool for Disaster Risk Assessment at UNION COUNCIL Level

2015 FLOOD RISK ASSESSMENT REPORT A Hi-Tech Knowledge Management Tool for Disaster Risk Assessment at UNION COUNCIL Level A PROPOSAL IN VIEW OF LESSONS LEARNED ISBN (P) 978-969-638-093-1 ISBN (D) 978-969-638-094-8 205-C 2nd Floor, Evacuee Trust Complex, F-5/1, Islamabad 195-1st Floor, Deans Trade Center, Peshawar Cantt; Peshawar Landline: +92.51.282.0449, +92.91.525.3347 E-mail: [email protected], Website: www.alhasan.com ALHASAN SYSTEMS PRIVATE LIMITED A Hi-Tech Knowledge Management, Business Psychology Modeling, and Publishing Company 205-C, 2nd Floor, Evacuee Trust Complex, Sector F-5/1, Islamabad, Pakistan 44000 195-1st Floor, Dean Trade Center, Peshawar Can ; Peshawar, Pakistan 25000 Landline: +92.51.282.0449, +92.91.525.3347 Fax: +92.51.835.9287 Email: [email protected] Website: www.alhasan.com Facebook: www.facebook.com/alhasan.com Twi er: @alhasansystems w3w address: *Alhasan COPYRIGHT © 2015 BY ALHASAN SYSTEMS All rights reserved. No part of this publica on may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmi ed, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior wri en permission of ALHASAN SYSTEMS. 58 p.; 8.5x11.5 = A3 Size Map ISBN (P) 978-969-638-093-1 ISBN (D) 978-969-638-094-8 CATALOGING REFERENCE: Disaster Risk Reduc on – Disaster Risk Management – Disaster Risk Assessment Hyogo Framework for Ac on 2005-2015 Building the Resilience of Na ons and Communi es to Disasters IDENTIFY, ACCESS, AND MONITOR DISASTER RISKS AND ENHANCE EARLY WARNING x Risk assessments -

Flood Emergency Reconstruction and Resilience Project Project

Flood Emergency Reconstruction and Resilience Project (RRP PAK 49038) Project Administration Manual Project Number: 49038-001 Loan and Technical Assistance Numbers: {LXXXX; TAXXXX} June 2015 Islamic Republic of Pakistan: Flood Emergency Reconstruction and Resilience Project i Project Administration Manual Purpose and Process The project administration manual (PAM) describes the essential administrative and management requirements to implement the project on time, within budget, and in accordance with Government and Asian Development Bank (ADB) policies and procedures. The PAM should include references to all available templates and instructions either through linkages to relevant URLs or directly incorporated in the PAM. The executing and implementing agencies are wholly responsible for the implementation of ADB financed projects, as agreed jointly between the borrower and ADB, and in accordance with Government and ADB’s policies and procedures. ADB staff is responsible to support implementation including compliance by executing and implementing agencies of their obligations and responsibilities for project implementation in accordance with ADB’s policies and procedures. At Loan Negotiations the borrower and ADB shall agree to the PAM and ensure consistency with the Loan and Project agreements. Such agreement shall be reflected in the minutes of the Loan Negotiations. In the event of any discrepancy or contradiction between the PAM and the Loan and Project Agreements, the provisions of the Loan and Project Agreements shall prevail. After ADB Board approval of the project's report and recommendations of the President (RRP) changes in implementation arrangements are subject to agreement and approval pursuant to relevant Government and ADB administrative procedures (including the Project Administration Instructions) and upon such approval they will be subsequently incorporated in the PAM. -

First Season Progress Report

Executive Summary EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1.0 INTRODUCTION Directorate of Energy, Government of Himachal Pradesh had undertaken the task of conducting Cumulative Environmental Impact Assessment (CEIA) Study for Chenab river basin in Himachal Pradesh with an objective to assess the cumulative impacts of hydropower development in the basin. State Government committed to conduct the study, in response to CWPIL No 24/09 (Shukla Committee Report), before the honourable High Court of Himachal Pradesh. The study is an important part of the World Bank‟s DPL (Development Policy Loan) to Government of Himachal Pradesh and also to meet the obligation under Ministry of Environment Forest & Climate Change‟s (MoEF&CC) OM No. J-11013/1/2013- IA-I dated May 28, 2013, which requires state government‟s to undertake carrying capacity study of river basin within their states. Terms of Reference (TOR) for the study were prepared by Directorate of Energy, Government of Himachal Pradesh and discussed and finalized in 55th meeting of Expert Appraisal Committee (EAC) for River Valley and Hydroelectric Projects of MoEF&CC held on 10th February, 2012. RS Envirolink Technologies Pvt. Ltd. (RSET), Gurgaon was awarded the study based on techno-commercial bidding. Contract was signed during November 2012 to complete the study in 18 months; however, due to some additional scope and limited accessibility to the area, the work got delayed and final report could be completed in November 2015. In the mean time, MoEF&CC has taken over all the river basin/carrying capacity studies being conducted by Central/State agencies and therefore, final report is submitted directly to MoEF&CC. -

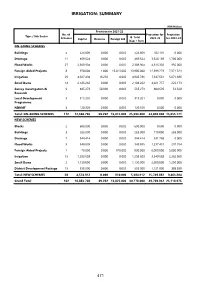

Irrigation: Summary

IRRIGATION: SUMMARY (PKR Million) Provision for 2021-22 No. of Projection for Projection Type / Sub Sector G. Total Schemes Capital Revenue Foreign Aid 2022-23 for 2023-24 (Cap + Rev) ON-GOING SCHEMES Buildings 5 528.809 0.000 0.000 528.809 702.197 0.000 Drainage 11 469.524 0.000 0.000 469.524 3,928.169 1,786.060 Flood Works 27 2,308.904 0.000 0.000 2,308.904 4,816.302 950.000 Foreign Aided Projects 8 970.000 1.000 13,015.000 13,986.000 12,399.279 7,571.324 Irrigation 29 4,927.494 18.292 0.000 4,945.786 7,347.661 5,071.686 Small Dams 14 2,183.262 0.000 0.000 2,183.262 4,021.757 222.173 Survey Investigation & 9 485.273 50.000 0.000 535.273 804.695 54.528 Research Local Development 5 315.201 0.000 0.000 315.201 0.000 0.000 Programme NDRMF 4 120.329 0.000 0.000 120.329 0.000 0.000 Total: ON-GOING SCHEMES 112 12,308.796 69.292 13,015.000 25,393.088 34,020.060 15,655.771 NEW SCHEMES Blocks 2 600.000 0.000 0.000 600.000 0.000 0.000 Buildings 3 265.000 0.000 0.000 265.000 710.000 265.000 Drainage 7 344.414 0.000 0.000 344.414 531.768 0.000 Flood Works 5 348.895 0.000 0.000 348.895 1,237.431 297.764 Foreign Aided Projects 1 20.000 0.000 810.000 830.000 6,000.000 5,000.000 Irrigation 15 1,293.603 0.000 0.000 1,293.603 3,549.683 2,262.060 Small Dams 2 1,150.000 0.000 0.000 1,150.000 2,600.000 1,250.000 District Development Package 15 553.000 0.000 0.000 553.000 1,121.000 388.380 Total: NEW SCHEMES 50 4,574.912 0.000 810.000 5,384.912 15,749.882 9,463.204 Grand Total 162 16,883.708 69.292 13,825.000 30,778.000 49,769.942 25,118.975 471 Irrigation (PKR Million) Accum. -

Investigation of Isotopes and Hydrological Processes in Indus River System, Pakistan

PINSTECH- 215 INVESTIGATION OF ISOTOPES AND HYDROLOGICAL PROCESSES IN INDUS RIVER SYSTEM, PAKISTAN Manzoor Ahmad Zahid Latif Jamil Ahmad Tariq Waheed Akram Muhammad Rafique . Isotope Application Division Directorate of Technology Pakistan Institute of Nuclear Science and Technology P.O. Nilore, Islamabad, Pakistan November, 2009 ABSTRACT Indus River, one of the longest rivers in the World, has five major eastern tributaries viz. Bias, Sutlej, Ravi, Chenab and Jhelum) while many small rivers join it from the right side among which Kabul River is the biggest with its main tributaries, the Swat, Panjkora and Kunar. All these main rivers are perennial and originate from the mountains. Basic sources of these rivers are snowmelt, rainfall and under certain conditions seepage from the formations. Different water sources are labeled with different isotope signatures which are used as fingerprints for identifying source and movement of water, geochemical and/or hydrological processes, and dynamics (age of water). Monitoring of isotopes in rivers can also enhance understanding of the water cycle of large river basins and to assess impacts of environmental and climatic changes on the water cycle. Therefore, a national network of suitable stations was established for isotopic monitoring of river waters in Indus Basin with specific objectives to study temporal variations of isotopes (2H, 18O and 3H), understand water cycles and hydrological processes in the catchments of these rivers, and to develop comprehensive database to support future isotope-based groundwater studies in the basin on recharge mechanism, water balance and monitoring of ongoing environmental changes. Water samples were collected during 2002-2006 on monthly basis from more than 20 stations at the major rivers and analyzed for 18O, 2H and 3H isotopes. -

Punjab Thermal Power (Private) Limited (PTPL)

VIS Credit Rating Company Limited www.vis.com.pk FINAL REPORT Punjab Thermal Power (Private) Limited (PTPL) REPORT DATE: RATING DETAILS 10 June, 2020 Rating Category Initial Rating RATING ANALYSTS: Long-term Short-term Entity AA- A-1 Maham Qasim Rating Outlook Stable [email protected] Rating Date 10th June’20 COMPANY INFORMATION Incorporated in 2017 Private Limited Company Key Shareholders (with stake 10% or more): Government of the Punjab – 100% Chairman: Mohammad Ali Chief Executive Officer: Mr. Akhtar Hussain Mayo APPLICABLE METHODOLOGY(IES) VIS Entity Rating Criteria Corporates (May 2019) https://www.vis.com.pk/kc-meth.aspx VIS Credit Rating Company Limited www.vis.com.pk Punjab Thermal Power (Pvt.) Limited (PTPL) OVERVIEW OF THE RATING RATIONALE INSTITUTION Punjab Thermal Power The ratings assigned to Punjab Thermal Power (Private) Limited (PTPL) incorporate its (Private) Limited was strong ownership profile being wholly owned by a sub-sovereign, Government of Punjab incorporated as a private (GoPb) through Energy Department. Moreover, underlying economic risk factors are largely limited company under the mitigated by initialing of 30 year-long power purchase agreement (PPA), in pursuance of Companies Act2017 on ECC decision with Central Power Purchasing Agency Guarantee Limited (CPPA-G) which June 08, 2017. The principal activity of the shall be signed by Mid of June 2020. The ratings also draw comfort from government company is to build, own, guaranteed cash flow stream under the agreement upon meeting certain performance operate and maintain a benchmarks. The ratings remain dependent upon timely completion of the project as per thermal plant having a total terms of agreement with the power purchaser. -

Seasonal Variations in Diversity and Distribution of Avian Fauna In

et International Journal on Emerging Technologies 11 (5): 647-651(2020) ISSN No. (Print): 0975-8364 ISSN No. (Online): 2249-3255 Seasonal Variations in Diversity and Distribution of Avian Fauna in Trimmu Barrage at District Jhang Punjab, Pakistan Muhammad Hashim Khan 1, Mehtab Alam 2, Fozia 3, Atta Ur Rehman 4, Yasir Ihtesham 4, Saghir Imdad Hassan 5, Wasif Ullah 6, Moniba Zahid Mahmood 7 and Saira Naz 8* 1Faculty of Veterinary and Animal Sciences Gomal University D.I. Khan, KP, Pakistan. 2Department of Biochemistry Azad Jammu & Azad Kashmir Medical College Muzaffarabad. 3Biochemistry department KMU Institute of Medical Sciences Kohat, KP, Pakistan. 4Institute of Biological Sciences, Gomal University D.I. Khan, KP, Pakistan. 5Gomal College of Veterinary Sciences Gomal University, D.I. Khan KP, Pakistan. 6Department of Zoology, Islamia College University, Peshawar, KP, Pakistan. 7Department of Environmental Science COMSATS University Islamabad, Abbottabad Campus. 8Department of Biological Sciences, University of Lahore Sargodha Campus. (Corresponding author: Saira Naz) (Received 19 October 2020, Revised 27 November 2020, Accepted 18 December 2020) (Published by Research Trend, Website: www.researchtrend.net) ABSTRACT: Pakistan is prosperous country in case of biodiversity and contains many areas which are the important habitats for different flora and fauna. Pakistan catches the attention of variety of birds due to diverse ecosystem. Birds are important to maintain the balance of ecosystems by providing various ecological services. Current study assesses the seasonal variation in the population of birds in Trimmu Barrage at Jhang district for the period of one year (May 2018-April 2019). Direct or indirect methods were used to collect the avifaunal data and meetings with locals were done. -

Assessment of Fish Assemblage in Highly Human Managed Reservoirs

y & E sit nd er a v n i g d e Journal of Biodiversity & Endangered o i r e Kausar et al., J Biodivers Endanger Species 2018, B d f S o 6:2 p l e a c ISSN:n 2332-2543 r i Species DOI: 10.4172/2332-2543.1000216 e u s o J Research Article Open Access Assessment of Fish Assemblage in Highly Human Managed Reservoirs Located on River Chenab, Pakistan Firdaus Kausar*, Umm e Aiman, Abdul Qadir and Sajid Rashid Ahmad College of Earth and Environmental Sciences, University of the Punjab, New Campus, Lahore, Pakistan *Corresponding author: Kausar F, College of Earth and Environmental Sciences, University of the Punjab, New Campus, Lahore, Pakistan, Tel: +04414475151; E-mail: [email protected] Received date: April 20, 2018; Accepted date: June 13, 2018; Published date: June 21, 2018 Copyright: ©2018 Kausar F, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited. Abstract River Chenab is one of the highly hydrologically managed rivers in South Asia and facing several environmental issues related to human population growth, industrialization, agricultural advancements and rapid urbanization. These issues are the major threat to the fish diversity of the River Chenab. In this regard, the present study was designed to elucidate the fish diversity, distribution patterns, conservation issues at five artificial water reservoirs (barrages) during the pre-monsoon and post-monsoon season in river Chenab, Pakistan.