1Part.Pdf (4.174Mb)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

IRN Population Movement Snapshot June 2021

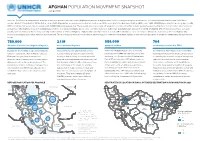

AFGHAN POPULATION MOVEMENT SNAPSHOT June 2021 Since the 1979 Soviet invasion and the subsequent waves of violence that have rocked Afghanistan, millions of Afghans have fled the country, seeking safety elsewhere. The Islamic Republic of Iran boasts 5,894 km of borders. Most of it, including the 921 km that are shared with Afghanistan, are porous and located in remote areas. While according to the Government of Iran (GIRI), some 1,400-2,500 Afghans arrive in Iran every day, recently GIRI has indicated increased daily movements with 4,000-5,000 arriving every day. These people aren’t necesserily all refugees, it is a mixed flow that includes people being pushed by the lack of economic opportunities as well as those who might be in need of international protection. The number fluctuates due to socio-economic challenges both in Iran and Afghanistan and also the COVID-19 situation. UNHCR Iran does not have access to border points and thus is unable to independently monitor arrivals or returns of Afghans. Afghans who currently reside in Iran have dierent statuses: some are refugees (Amayesh card holders), other are Afghans who posses a national passport, while other are undocumented. These populations move across borders in various ways. it is understood that many Afghans in Iran who have passports or are undocumented may have protection needs. 780,000 2.1 M 586,000 704 Amayesh Card Holders (Afghan refugees1) undocumented Afghans passport holders voluntarily repatriated in 2021 In 2001, the Government of Iran issues Amayesh Undocumented is an umbrella term used to There are 275,000 Afghans who hold family Covid-19 had a clear impact on the low VolRep cards to regularize the stay of Afghan refugees. -

The Hymns of Zoroaster: a New Translation of the Most Ancient Sacred Texts of Iran Pdf

FREE THE HYMNS OF ZOROASTER: A NEW TRANSLATION OF THE MOST ANCIENT SACRED TEXTS OF IRAN PDF M. L. West | 182 pages | 15 Dec 2010 | I.B.Tauris & Co Ltd | 9781848855052 | English | London, United Kingdom The Hymns of Zoroaster : M. L. West : See what's new with book lending at the Internet Archive. Search icon An illustration of a magnifying glass. User icon An illustration of a person's head and chest. Sign up Log in. Web icon An illustration of a computer application window Wayback Machine Texts icon An illustration of an open book. Books Video icon An illustration of two cells of a film strip. Video Audio icon An illustration of an audio speaker. Audio Software icon An illustration of a 3. Software Images icon An illustration of two photographs. Images Donate icon An illustration of a heart shape Donate Ellipses icon An illustration of text ellipses. Full text of " The Hymns Of Zoroaster. West has produced a lucid interpretation of those ancient words. His renditions are filled with insights and empathy. This endeavour is an important contribution toward understanding more fully some of the earliest prophetic words in human history. West's book will be widely welcomed, by students and general readers alike. West resuscitates the notion of Zoroaster as the self-conscious founder of a new religion. In advancing this idea, he takes position against many modern interpreters of these extremely difficult texts. The clarity and beauty of his translation will be much welcomed by students of Zoroastrianism and by Zoroastrians themselves, while his bold interpretation will spark off welcome debate among specialists. -

What an Auspicious Day Today Is! It Is Pak Iranshah Atash Behram Padshah Saheb's Salgreh – Adar Mahino and Adar Roj! Adar Ma

Weekly Zoroastrian Scripture Extract # 102 – Pak Iranshah Atash Behram Padshah Salgreh - Adar Mahino and Adar Roj Parab - We approach Thee Ahura Mazda through Thy Holy Fire - Yasna Haptanghaaiti - Moti Haptan Yasht - Yasna 36 Verses 1 - 3 Hello all Tele Class friends: What an auspicious day today is! It is Pak Iranshah Atash Behram Padshah Saheb’s Salgreh – Adar Mahino and Adar Roj! Adar Mahina nu Parab! Today in our Udvada Gaam, hundreds of Humdins from all over India will congregate to pay their homage to Padshah Saheb and then all of them will be treated by a sumptuous Gahambar Lunch thanks to the Petit Family, an annual event! Over 1500 Humdins will partake this Gahambar lunch! I have attached 3 photos of the Salgreh in 2004 showing the long queue, Gahambar lunch Pangat and the Master Chefs! In our religion, Fire is regarded as one of the most amazing creations of Dadar Ahura Mazda! In fact, in Atash Nyayesh, Fire is referred to as the Son of Ahura Mazda! In our Agiyaris, Adarans and Atash Behrams, the focal point of our worship is the consecrated Fire and hence many people call us Fire Worshippers in their ignorance. That brings to mind the famous quote of the great Persian poet, Ferdowsi, the Shahnameh Author: “Ma gui keh Atash parastand budan, Parastandeh Pak Yazdaan budan!” “Do not say that they are Fire Worshippers! They are worshippers of Pak Yazdaan (Dadar Ahura Mazda) (through Holy Fire!)” In our previous weeklies, we have presented verses from Atash Nyayesh in praise of our consecrated Fires! The above point by Ferdowsi is well supported by the second Karda (chapter) of Yasna Haptanghaaiti, Yasna 36, the seven Has (chapters) attributed by some to Zarathushtra himself after his Gathas and many attribute them to the immediate disciples of Zarathushtra. -

Iran: Ethnic and Religious Minorities

Order Code RL34021 Iran: Ethnic and Religious Minorities Updated November 25, 2008 Hussein D. Hassan Information Research Specialist Knowledge Services Group Iran: Ethnic and Religious Minorities Summary Iran is home to approximately 70.5 million people who are ethnically, religiously, and linguistically diverse. The central authority is dominated by Persians who constitute 51% of Iran’s population. Iranians speak diverse Indo-Iranian, Semitic, Armenian, and Turkic languages. The state religion is Shia, Islam. After installation by Ayatollah Khomeini of an Islamic regime in February 1979, treatment of ethnic and religious minorities grew worse. By summer of 1979, initial violent conflicts erupted between the central authority and members of several tribal, regional, and ethnic minority groups. This initial conflict dashed the hope and expectation of these minorities who were hoping for greater cultural autonomy under the newly created Islamic State. The U.S. State Department’s 2008 Annual Report on International Religious Freedom, released September 19, 2008, cited Iran for widespread serious abuses, including unjust executions, politically motivated abductions by security forces, torture, arbitrary arrest and detention, and arrests of women’s rights activists. According to the State Department’s 2007 Country Report on Human Rights (released on March 11, 2008), Iran’s poor human rights record worsened, and it continued to commit numerous, serious abuses. The government placed severe restrictions on freedom of religion. The report also cited violence and legal and societal discrimination against women, ethnic and religious minorities. Incitement to anti-Semitism also remained a problem. Members of the country’s non-Muslim religious minorities, particularly Baha’is, reported imprisonment, harassment, and intimidation based on their religious beliefs. -

ABMBNIA (Varmio) B. H. KENNETT. ARMENIA

HI ABMBNIA (Varmio) •with any such supposition. It ia a safe inference indistinguishable. la timea of need c? danger from 1 S 67fl;, 2 S (33rr- that the recognized method man requires a god that ia near, and nofc a god of carrying the Ark in early times was in a sacred that is far off. It ia bjy BO means a primitive con- cart (i.e, a cart that had been used for no other ception which we find an the dedicatory prayer put purpose) drawn by COTVS or bulls.* The use of into the mouth of Solomon (1K 84*1*), that, if people horned cattle might possibly denote that the Ark go out to battle against their enemy, and they was in some way connected with lunar worship; prayto their God towards the house which is built in any case, Jiowever, they probably imply that to His name, He will make their prayer and the god contained in the Ark was regarded aa the supplication hoard to the heaven in which He god of fertility (see Frazer, Adonis, Attu, Osiris, really dwells,* Primitive warriors wanted to have pp. 46,80),f At first sight it is difficult to suppose their goda in their midst. Of what use was the that a aerpent could ever be regarded aa a god of Divine Father (see Nu 2129) at home, when his sona fertility, but "whatever the origin of serpent-worship were in danger in the field ? It waa but natural, may be—and we need not assume that it has been therefore, that the goda should be carried out everywhere identical — there can be little doubt wherever their help waa needed (2S 5ai; cf. -

Neue Wache (1818-1993) Since 1993 in the Federal Republic of Germany the Berlin Neue Wache Has Served As a Central Memorial Comm

PRZEGLĄD ZACHODNI 2011, No 1 ZbIGNIEw MAZuR Poznań NEUE WACHE (1818-1993) Since 1993 in the Federal Republic of Germany the berlin Neue wache has served as a central memorial commemorating the victims of war and tyranny, that is to say it represents in a synthetic gist the binding German canon of collective memo- ry in the most sensitive area concerning the infamous history of the Third Reich. The interior decor of Neue wache, the sculpture placed inside and the commemorative plaques speak a lot about the official historical policy of the German government. Also the symbolism of the place itself is of significance, and a plaque positioned to the left of the entrance contains information about its history. Indeed, the history of Neue wache was extraordinary, starting as a utility building, though equipped with readable symbolic features, and ending up as a place for a national memorial which has been redesigned three times. Consequently, the process itself created a symbolic palimpsest with some layers completely obliterated and others remaining visible to the eye, and with new layers added which still retain a scent of freshness. The first layer is very strongly connected with the victorious war of “liberation” against Na- poleonic France, which played the role of a myth that laid the foundations for the great power of Prussia and then of the later German Empire. The second layer was a reflection of the glorifying worship of the fallen soldiers which developed after world war I in European countries and also in Germany. The third one was an ex- pression of the historical policy of the communist-run German Democratic Republic which emphasized the victims of class struggle with “militarism” and “fascism”. -

Late Onset of Sufism in Azerbaijan and the Influence of Zarathustra Thoughts on Its Fundamentals

International Journal of Philosophy and Theology September 2014, Vol. 2, No. 3, pp. 93-106 ISSN: 2333-5750 (Print), 2333-5769 (Online) Copyright © The Author(s). 2014. All Rights Reserved. Published by American Research Institute for Policy Development DOI: 10.15640/ijpt.v2n3a7 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.15640/ijpt.v2n3a7 Late Onset of Sufism in Azerbaijan and the Influence of Zarathustra Thoughts on its Fundamentals Parisa Ghorbannejad1 Abstract Islamic Sufism started in Azerbaijan later than other Islamic regions for some reasons.Early Sufis in this region had been inspired by mysterious beliefs of Zarathustra which played an important role in future path of Sufism in Iran the consequences of which can be seen in illumination theory. This research deals with the reason of the delay in the advent of Sufism in Azerbaijan compared with other regions in a descriptive analytic method. Studies show that the deficiency of conqueror Arabs, loyalty of ethnic people to Iranian religion and the influence of theosophical beliefs such as heart's eye, meeting the right, relation between body and soul and cross evidences in heart had important effects on ideas and thoughts of Azerbaijan's first Sufis such as Ebn-e-Yazdanyar. Investigating Arab victories and conducting case studies on early Sufis' thoughts and ideas, the author attains considerable results via this research. Keywords: Sufism, Azerbaijan, Zarathustra, Ebn-e-Yazdanyar, Islam Introduction Azerbaijan territory2 with its unique geography and history, was the cultural center of Iran for many years in Sasanian era and was very important for Zarathustra religion and Magi class. 1 PhD, Faculty of Science, Islamic Azad University, Urmia Branch,WestAzarbayjan, Iran. -

Altona War Memorials.Pages

ALTONA MEMORIAL DRINKING FOUNTAIN by Ann Cassar GIFT TO ALTONA A memorial commemorating those who lost their lives while serving in the Australian Imperial Force (AIF) during World War I 1914-1918 (Great War), unveiled in 1928 on the tenth anniversary after the war ended Fig 1 - Image from Altona Laverton Historical Society collection, circa 1929 Located at the northern end of Altona pier on the Esplanade, the memorial was a gift to the community from the recently formed Ex-Service Men and Women’s Club, now better known as the Altona RSL (Returned Services League) and local residents who generously donated to the cause. The memorial was unveiled on Monday, 4 June 1928 on the day when the King’s birthday was celebrated, and 10 years after the end of WWI. Fig 2 - Request for tenders published in The Age, Thursday, 1 Mar 1928 Jack Hopkins, treasurer of the Ex-Service Men and Women’s Club, designed the memorial and carried out much of its construction starting on 1 May 1928, just one month before the unveiling. Constructed of concrete, it had four alcoves, one on each side and when completed there would be a tap in each to supply unlimited quantities the world’s oldest brew, “Adam’s Ale.” It was surmounted by a dome on top and would be further embellished as funds became available. The completed memorial stood eight feet high (2.4mt) with two drinking taps. A plaque had been mounted above the front opening bearing the words Erected by Altona Ex-Service Men & Womens Club 1914-1918 “Lest We Forget.” Opening Ceremony In a ceremony beginning at 3pm on Monday, 4 June 1928, the day when the King’s birthday was celebrated. -

The Cost of Memorializing: Analyzing Armenian Genocide Memorials and Commemorations in the Republic of Armenia and in the Diaspora

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL FOR HISTORY, CULTURE AND MODERNITY www.history-culture-modernity.org Published by: Uopen Journals Copyright: © The Author(s). Content is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International Licence eISSN: 2213-0624 The Cost of Memorializing: Analyzing Armenian Genocide Memorials and Commemorations in the Republic of Armenia and in the Diaspora Sabrina Papazian HCM 7: 55–86 DOI: 10.18352/hcm.534 Abstract In April of 1965 thousands of Armenians gathered in Yerevan and Los Angeles, demanding global recognition of and remembrance for the Armenian Genocide after fifty years of silence. Since then, over 200 memorials have been built around the world commemorating the vic- tims of the Genocide and have been the centre of hundreds of marches, vigils and commemorative events. This article analyzes the visual forms and semiotic natures of three Armenian Genocide memorials in Armenia, France and the United States and the commemoration prac- tices that surround them to compare and contrast how the Genocide is being memorialized in different Armenian communities. In doing so, this article questions the long-term effects commemorations have on an overall transnational Armenian community. Ultimately, it appears that calls for Armenian Genocide recognition unwittingly categorize the global Armenian community as eternal victims, impeding the develop- ment of both the Republic of Armenia and the Armenian diaspora. Keywords: Armenian Genocide, commemoration, cultural heritage, diaspora, identity, memorials HCM 2019, VOL. 7 Downloaded from Brill.com10/05/202155 12:33:22PM via free access PAPAZIAN Introduction On 24 April 2015, the hundredth anniversary of the commencement of the Armenian Genocide, Armenians around the world collectively mourned for and remembered their ancestors who had lost their lives in the massacres and deportations of 1915.1 These commemorations took place in many forms, including marches, candlelight vigils, ceremo- nial speeches and cultural performances. -

Koosan Fire Temple in the Heart of Tabarestan Mountains

The Forgotten Ancient Fire Temples of Iran. Compiled by Phil Masters Koosan Fire Temple in the heart of Tabarestan mountains Aftab Yazdani: Koosan (or Toosan) Fire Temple in Behshahr, is one of the countless fire temples remaining from the Sassanian era. Zahireddin has called it Koosan in his book, where he says: “The son of Qobad built a fire temple in that place.” Based on notes from Ebn Esfandiar, on this fire temple a military camp was built by the Arabs. However, the discovery of ancient relics and a whole lot of coins from the Sassanian era proves the value and importance that this place had for the Sassanians. This fire Temple is situated 4 km on the west of Behshahr. Enb Esfandiar has written about this fire temple and says that: “Firooz Shah, and possibly the Sassanian Firooz has visited this Fire Temple.” This Fire Temple is on the southwest of Assiabesar Village, on top of a small mountain, and has been registered in the national heritage list under No. 5410. The structure is 8.5 X 8.5 m in size. It is built of stone and mortar (plaster of lime and ash or sand) and the outside surface of the walls have been built with stones laid orderly with geometrical pattern, and the walls have been filled with shavings and earth. Behshahr is a city on the east of Mazandaran province. Kouhestan Village is 6 km on the west of Behshahr district. The old name of Kouhestan was Koosan and its age is estimated to go back to the pre-Islamic period. -

Country Profile – Azerbaijan

Country profile – Azerbaijan Version 2008 Recommended citation: FAO. 2008. AQUASTAT Country Profile – Azerbaijan. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO). Rome, Italy The designations employed and the presentation of material in this information product do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) concerning the legal or development status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The mention of specific companies or products of manufacturers, whether or not these have been patented, does not imply that these have been endorsed or recommended by FAO in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. The views expressed in this information product are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of FAO. FAO encourages the use, reproduction and dissemination of material in this information product. Except where otherwise indicated, material may be copied, downloaded and printed for private study, research and teaching purposes, or for use in non-commercial products or services, provided that appropriate acknowledgement of FAO as the source and copyright holder is given and that FAO’s endorsement of users’ views, products or services is not implied in any way. All requests for translation and adaptation rights, and for resale and other commercial use rights should be made via www.fao.org/contact-us/licencerequest or addressed to [email protected]. FAO information products are available on the FAO website (www.fao.org/ publications) and can be purchased through [email protected]. -

Summer/June 2014

AMORDAD – SHEHREVER- MEHER 1383 AY (SHENSHAI) FEZANA JOURNAL FEZANA TABESTAN 1383 AY 3752 Z VOL. 28, No 2 SUMMER/JUNE 2014 ● SUMMER/JUNE 2014 Tir–Amordad–ShehreverJOUR 1383 AY (Fasli) • Behman–Spendarmad 1383 AY Fravardin 1384 (Shenshai) •N Spendarmad 1383 AY Fravardin–ArdibeheshtAL 1384 AY (Kadimi) Zoroastrians of Central Asia PUBLICATION OF THE FEDERATION OF ZOROASTRIAN ASSOCIATIONS OF NORTH AMERICA Copyright ©2014 Federation of Zoroastrian Associations of North America • • With 'Best Compfiments from rrhe Incorporated fJTustees of the Zoroastrian Charity :Funds of :J{ongl(pnffi Canton & Macao • • PUBLICATION OF THE FEDERATION OF ZOROASTRIAN ASSOCIATIONS OF NORTH AMERICA Vol 28 No 2 June / Summer 2014, Tabestan 1383 AY 3752 Z 92 Zoroastrianism and 90 The Death of Iranian Religions in Yazdegerd III at Merv Ancient Armenia 15 Was Central Asia the Ancient Home of 74 Letters from Sogdian the Aryan Nation & Zoroastrians at the Zoroastrian Religion ? Eastern Crosssroads 02 Editorials 42 Some Reflections on Furniture Of Sogdians And Zoroastrianism in Sogdiana Other Central Asians In 11 FEZANA AGM 2014 - Seattle and Bactria China 13 Zoroastrians of Central 49 Understanding Central 78 Kazakhstan Interfaith Asia Genesis of This Issue Asian Zoroastrianism Activities: Zoroastrian Through Sogdian Art Forms 22 Evidence from Archeology Participation and Art 55 Iranian Themes in the 80 Balkh: The Holy Land Afrasyab Paintings in the 31 Parthian Zoroastrians at Hall of Ambassadors 87 Is There A Zoroastrian Nisa Revival In Present Day 61 The Zoroastrain Bone Tajikistan? 34 "Zoroastrian Traces" In Boxes of Chorasmia and Two Ancient Sites In Sogdiana 98 Treasures of the Silk Road Bactria And Sogdiana: Takhti Sangin And Sarazm 66 Zoroastrian Funerary 102 Personal Profile Beliefs And Practices As Shown On The Tomb 104 Books and Arts Editor in Chief: Dolly Dastoor, editor(@)fezana.org AMORDAD SHEHREVER MEHER 1383 AY (SHENSHAI) FEZANA JOURNAL FEZANA Technical Assistant: Coomi Gazdar TABESTAN 1383 AY 3752 Z VOL.