Marat Grebennikov, Concordia University the Puzzle of a Loyal Minority: Why Do Azeris Support the Iranian State? Abstract Ever

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Volume II, Issue 2, March 2021.Pages

INTERNATIONAL COUNTER-TERRORISM REVIEW VOLUME II, ISSUE 2 February, 2021 The Revival of Islam How Do External Factors Shape the Potential Islamist Threat in Azerbaijan? FUAD SHAHBAZOV ABOUT ICTR The International Counter-Terrorism Review (ICTR) aspires to be the world’s leading student publication in Terrorism & Counter-Terrorism Studies. ICTR provides a unique opportunity for students and young professionals to publish their papers, share innovative ideas, and develop an academic career in Counter-Terrorism Studies. The publication also serves as a platform for exchanging research and policy recommendations addressing theoretical, empirical and policy dimensions of international issues pertaining to terrorism, counter-terrorism, insurgency, counter-insurgency, political violence and homeland security. ICTR is a project jointly initiated by the International Institute for Counter-Terrorism (ICT) at the Interdisciplinary Center (IDC), Herzliya, Israel and NextGen 5.0. The International Institute for Counter-Terrorism (ICT) is one of the leading academic institutes for counter-terrorism in the world. Founded in 1996, ICT has rapidly evolved into a highly esteemed global hub for counter-terrorism research, policy recommendations and education. The goal of the ICT is to advise decision makers, to initiate applied research and to provide high-level consultation, education and training in order to address terrorism and its effects. NextGen 5.0 is a pioneering non-profit, independent, and virtual think tank committed to inspiring and empowering the next generation of peace and security leaders in order to build a more secure and prosperous world. COPYRIGHT This material is offered free of charge for personal and non-commercial use, provided the source is acknowledged. -

IRN Population Movement Snapshot June 2021

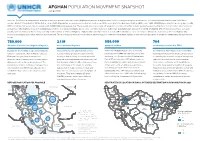

AFGHAN POPULATION MOVEMENT SNAPSHOT June 2021 Since the 1979 Soviet invasion and the subsequent waves of violence that have rocked Afghanistan, millions of Afghans have fled the country, seeking safety elsewhere. The Islamic Republic of Iran boasts 5,894 km of borders. Most of it, including the 921 km that are shared with Afghanistan, are porous and located in remote areas. While according to the Government of Iran (GIRI), some 1,400-2,500 Afghans arrive in Iran every day, recently GIRI has indicated increased daily movements with 4,000-5,000 arriving every day. These people aren’t necesserily all refugees, it is a mixed flow that includes people being pushed by the lack of economic opportunities as well as those who might be in need of international protection. The number fluctuates due to socio-economic challenges both in Iran and Afghanistan and also the COVID-19 situation. UNHCR Iran does not have access to border points and thus is unable to independently monitor arrivals or returns of Afghans. Afghans who currently reside in Iran have dierent statuses: some are refugees (Amayesh card holders), other are Afghans who posses a national passport, while other are undocumented. These populations move across borders in various ways. it is understood that many Afghans in Iran who have passports or are undocumented may have protection needs. 780,000 2.1 M 586,000 704 Amayesh Card Holders (Afghan refugees1) undocumented Afghans passport holders voluntarily repatriated in 2021 In 2001, the Government of Iran issues Amayesh Undocumented is an umbrella term used to There are 275,000 Afghans who hold family Covid-19 had a clear impact on the low VolRep cards to regularize the stay of Afghan refugees. -

CAUCASUS ANALYTICAL DIGEST No. 86, 25 July 2016 2

No. 86 25 July 2016 Abkhazia South Ossetia caucasus Adjara analytical digest Nagorno- Karabakh www.laender-analysen.de/cad www.css.ethz.ch/en/publications/cad.html TURKISH SOCIETAL ACTORS IN THE CAUCASUS Special Editors: Andrea Weiss and Yana Zabanova ■■Introduction by the Special Editors 2 ■■Track Two Diplomacy between Armenia and Turkey: Achievements and Limitations 3 By Vahram Ter-Matevosyan, Yerevan ■■How Non-Governmental Are Civil Societal Relations Between Turkey and Azerbaijan? 6 By Hülya Demirdirek and Orhan Gafarlı, Ankara ■■Turkey’s Abkhaz Diaspora as an Intermediary Between Turkish and Abkhaz Societies 9 By Yana Zabanova, Berlin ■■Turkish Georgians: The Forgotten Diaspora, Religion and Social Ties 13 By Andrea Weiss, Berlin ■■CHRONICLE From 14 June to 19 July 2016 16 Research Centre Center Caucasus Research German Association for for East European Studies for Security Studies Resource Centers East European Studies University of Bremen ETH Zurich CAUCASUS ANALYTICAL DIGEST No. 86, 25 July 2016 2 Introduction by the Special Editors Turkey is an important actor in the South Caucasus in several respects: as a leading trade and investment partner, an energy hub, and a security actor. While the economic and security dimensions of Turkey’s role in the region have been amply addressed, its cross-border ties with societies in the Caucasus remain under-researched. This issue of the Cauca- sus Analytical Digest illustrates inter-societal relations between Turkey and the three South Caucasus states of Arme- nia, Azerbaijan, and Georgia, as well as with the de-facto state of Abkhazia, through the prism of NGO and diaspora contacts. Although this approach is by necessity selective, each of the four articles describes an important segment of transboundary societal relations between Turkey and the Caucasus. -

Selected Works of Chokan Valikhanov Selected Works of Chokan Valikhanov

SELECTED WORKS OF CHOKAN VALIKHANOV CHOKAN OF WORKS SELECTED SELECTED WORKS OF CHOKAN VALIKHANOV Pioneering Ethnographer and Historian of the Great Steppe When Chokan Valikhanov died of tuberculosis in 1865, aged only 29, the Russian academician Nikolai Veselovsky described his short life as ‘a meteor flashing across the field of oriental studies’. Set against his remarkable output of official reports, articles and research into the history, culture and ethnology of Central Asia, and more important, his Kazakh people, it remains an entirely appropriate accolade. Born in 1835 into a wealthy and powerful Kazakh clan, he was one of the first ‘people of the steppe’ to receive a Russian education and military training. Soon after graduating from Siberian Cadet Corps at Omsk, he was taking part in reconnaissance missions deep into regions of Central Asia that had seldom been visited by outsiders. His famous mission to Kashgar in Chinese Turkestan, which began in June 1858 and lasted for more than a year, saw him in disguise as a Tashkent mer- chant, risking his life to gather vital information not just on current events, but also on the ethnic make-up, geography, flora and fauna of this unknown region. Journeys to Kuldzha, to Issyk-Kol and to other remote and unmapped places quickly established his reputation, even though he al- ways remained inorodets – an outsider to the Russian establishment. Nonetheless, he was elected to membership of the Imperial Russian Geographical Society and spent time in St Petersburg, where he was given a private audience by the Tsar. Wherever he went he made his mark, striking up strong and lasting friendships with the likes of the great Russian explorer and geographer Pyotr Petrovich Semyonov-Tian-Shansky and the writer Fyodor Dostoyevsky. -

British Persian Studies and the Celebrations of the 2500Th Anniversary of the Founding of the Persian Empire in 1971

British Persian Studies and the Celebrations of the 2500th Anniversary of the Founding of the Persian Empire in 1971 A thesis submitted to The University of Manchester for the degree of Master of Philosophy in the Faculty of Humanities. 2014 Robert Steele School of Arts, Languages and Cultures Contents Abstract ........................................................................................................................................................................ 4 Declaration .................................................................................................................................................................. 5 Copyright Statement ................................................................................................................................................ 5 Acknowledgements .................................................................................................................................................. 6 Introduction .......................................................................................................................................................................... 7 Objectives and Structure ............................................................................................................................................. 8 Literature Review .......................................................................................................................................................... 9 Statement on Primary Sources............................................................................................................................... -

Iran: Ethnic and Religious Minorities

Order Code RL34021 Iran: Ethnic and Religious Minorities Updated November 25, 2008 Hussein D. Hassan Information Research Specialist Knowledge Services Group Iran: Ethnic and Religious Minorities Summary Iran is home to approximately 70.5 million people who are ethnically, religiously, and linguistically diverse. The central authority is dominated by Persians who constitute 51% of Iran’s population. Iranians speak diverse Indo-Iranian, Semitic, Armenian, and Turkic languages. The state religion is Shia, Islam. After installation by Ayatollah Khomeini of an Islamic regime in February 1979, treatment of ethnic and religious minorities grew worse. By summer of 1979, initial violent conflicts erupted between the central authority and members of several tribal, regional, and ethnic minority groups. This initial conflict dashed the hope and expectation of these minorities who were hoping for greater cultural autonomy under the newly created Islamic State. The U.S. State Department’s 2008 Annual Report on International Religious Freedom, released September 19, 2008, cited Iran for widespread serious abuses, including unjust executions, politically motivated abductions by security forces, torture, arbitrary arrest and detention, and arrests of women’s rights activists. According to the State Department’s 2007 Country Report on Human Rights (released on March 11, 2008), Iran’s poor human rights record worsened, and it continued to commit numerous, serious abuses. The government placed severe restrictions on freedom of religion. The report also cited violence and legal and societal discrimination against women, ethnic and religious minorities. Incitement to anti-Semitism also remained a problem. Members of the country’s non-Muslim religious minorities, particularly Baha’is, reported imprisonment, harassment, and intimidation based on their religious beliefs. -

A Study of the Cultural Grounds in Formation and Growth of Ethnic Challenges in Azerbaijan, Iran

Journal of Ethnic and Cultural Studies Copyright 2018 2018, Vol. 5, No. 2, 64-76 ISSN: 2149-1291 A Study of the Cultural Grounds in Formation and Growth of Ethnic Challenges in Azerbaijan, Iran Mansour Salehi1, Bahram Navazeni2, Masoud Jafarinezhad3 This study has been conducted with the aim of finding the cultural bases of ethnic challenges in Azerbaijan and tried to provide the desired solutions for managing ethnic diversity in Iran and proper policy making in order to respect the components and the culture of the people towards increasing national solidarity. In this regard, this study investigates the cultural grounds of the formation and growth of ethnic challenges created and will be created after the Constitutional Revolution in Azerbaijan, Iran. Accordingly, the main question is that what is the most influential cultural ground in formation and growth of ethnic challenges in Azerbaijan? Research method was the in-depth interview, which was followed by an interview with 32 related experts, and after accessing all the results obtained, analysis of interview data and quotative analysis performed with in-depth interview. Findings of the research indicate that emphasis on the language of a country, cultural discrimination, and the non- implementation of Article 15 of the Constitution for the abandonment of Turkish speakers with 39% were the most important domestic cultural ground, and the impact of satellite channels in Turkey and Republic of Azerbaijan with 32% and superior Turkish identity in the vicinity of Azerbaijan with 31%, were the most important external grounds in formation and growth of ethnic challenges in Azerbaijan in Iran. -

Tribes and Empire on the Margins of Nineteenth-Century Iran

publications on the near east publications on the near east Poetry’s Voice, Society’s Song: Ottoman Lyric The Transformation of Islamic Art during Poetry by Walter G. Andrews the Sunni Revival by Yasser Tabbaa The Remaking of Istanbul: Portrait of an Shiraz in the Age of Hafez: The Glory of Ottoman City in the Nineteenth Century a Medieval Persian City by John Limbert by Zeynep Çelik The Martyrs of Karbala: Shi‘i Symbols The Tragedy of Sohráb and Rostám from and Rituals in Modern Iran the Persian National Epic, the Shahname by Kamran Scot Aghaie of Abol-Qasem Ferdowsi, translated by Ottoman Lyric Poetry: An Anthology, Jerome W. Clinton Expanded Edition, edited and translated The Jews in Modern Egypt, 1914–1952 by Walter G. Andrews, Najaat Black, and by Gudrun Krämer Mehmet Kalpaklı Izmir and the Levantine World, 1550–1650 Party Building in the Modern Middle East: by Daniel Goffman The Origins of Competitive and Coercive Rule by Michele Penner Angrist Medieval Agriculture and Islamic Science: The Almanac of a Yemeni Sultan Everyday Life and Consumer Culture by Daniel Martin Varisco in Eighteenth-Century Damascus by James Grehan Rethinking Modernity and National Identity in Turkey, edited by Sibel Bozdog˘an and The City’s Pleasures: Istanbul in the Eigh- Res¸at Kasaba teenth Century by Shirine Hamadeh Slavery and Abolition in the Ottoman Middle Reading Orientalism: Said and the Unsaid East by Ehud R. Toledano by Daniel Martin Varisco Britons in the Ottoman Empire, 1642–1660 The Merchant Houses of Mocha: Trade by Daniel Goffman and Architecture in an Indian Ocean Port by Nancy Um Popular Preaching and Religious Authority in the Medieval Islamic Near East Tribes and Empire on the Margins of Nine- by Jonathan P. -

ETHNIC INEQUALITY in IRAN: an OVERVIEW Akbar Aghajanian Fayetteville State University

Fayetteville State University DigitalCommons@Fayetteville State University Faculty Working Papers Sociology Department 1983 ETHNIC INEQUALITY IN IRAN: AN OVERVIEW Akbar Aghajanian Fayetteville State University Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.uncfsu.edu/soci Part of the Inequality and Stratification Commons Recommended Citation Aghajanian, Akbar, "ETHNIC INEQUALITY IN IRAN: AN OVERVIEW" (1983). Faculty Working Papers. 13. http://digitalcommons.uncfsu.edu/soci/13 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Sociology Department at DigitalCommons@Fayetteville State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Working Papers by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Fayetteville State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Int. J. Middle East Stud. 15 (1983), 211-224 Printed in the United States of America Akbar Aghajanian ETHNIC INEQUALITY IN IRAN: AN OVERVIEW INTRODUCTION Iran is a country of diverse ethnic and linguistic communities. There are Kurds in the west and northwest, Baluchis in the east, Turks in the north and northwest, and Arabs in the south. Persians are situated today in the central areas. Through the history of Iran these various ethnic groups have lived in geographically distinct regions and provinces. Along with this residential separa- tion, social and economic distance has long persisted and still continues among ethnic communities. Yet, regrettably, there is very little known about these inequalities in the contemporary history of Iran. A full examination of the historical development of the ethnic and linguistic communities in Iran is beyond the scope of this paper.' It is clear, however, that ethnic diversity goes back to pre-Islamic times. -

Azerbaijan Page 1 of 8

Azerbaijan Page 1 of 8 Azerbaijan BUREAU OF DEMOCRACY, HUMAN RIGHTS, AND LABOR International Religious Freedom Report 2009 October 26, 2009 The Constitution provides for freedom of religion. On March 18, 2009, however, a national referendum approved a series of amendments to the Constitution; two amendments limit the spreading of and propagandizing of religion. Additionally, on May 8, 2009, the Milli Majlis (Parliament) passed an amended Law on Freedom of Religion, signed by the President on May 29, 2009, which could result in additional restrictions to the system of registration for religious groups. In spite of these developments, the Government continued to respect the religious freedom of the majority of citizens, with some notable exceptions for members of religions considered nontraditional. There was some deterioration in the status of respect for religious freedom by the Government during the reporting period. There were changes to the Constitution that undermined religious freedom. There were mosque closures, and state- and locally sponsored raids on evangelical Protestant religious groups. There were reports of monitoring by federal and local officials as well as harassment and detention of both Islamic and nontraditional Christian groups. There were reports of discrimination against worshippers based on their religious beliefs, largely conducted by local authorities who detained and questioned worshippers without any legal basis and confiscated religious material. There were sporadic reports of societal abuses or discrimination based on religious affiliation, belief, or practice. There was some prejudice against Muslims who converted to other faiths, and there was occasional hostility toward groups that proselytized, particularly evangelical Christians, and other missionary groups. -

Russia's Migration Experience Pdf 0.52 MB

Valdai Papers #97 From Mistrust to Solidarity or More Mistrust? Russia’s Migration Experience in the International Context Dmitry Poletaev valdaiclub.com #valdaiclub December, 2018 About the Author Dmitry Poletaev Leading researcher at the Institute of Economic Forecasting of the Russian Academy of Sciences, Director of Migration Research Center This publication and other papers are available on http://valdaiclub.com/a/valdai-papers/ The views and opinions expressed in this paper are those of the authors and do not represent the views of the Valdai Discussion Club, unless explicitly stated otherwise. © The Foundation for Development and Support of the Valdai Discussion Club, 2018 42 Bolshaya Tatarskaya st., Moscow, 115184, Russia From Mistrust to Solidarity or More Mistrust? Russia’s Migration Experience in the International Context 3 The ease of transportation and communication in the modern world makes it possible to quickly deliver potential migrants to countries that they previously could only see on their television screens, hear about from family and friends living and working there, or read about in glossy magazines. A new era has dawned, different from anything humanity has ever experienced, and as the world becomes increasingly open to migration, the seeming simplicity of changing status, workplace and place of residence becomes all the more tempting. Unfortunately, ‘migration without borders’,1 once regarded as a promising strategy for the future, is increasingly viewed an undesirable outcome by a signifi cant number of people in host countries, and migrants can expect to fi nd solidarity mainly among fellow migrants and left-wing parties. Freedom of movement and freedom to choose a place of residence can be ranked among the category of freedoms which, as part of the Global Commons, have been restricted to varying degrees at the level of communities, states, and international associations. -

Islamic Activism in Azerbaijan: Repression and Mobilization in a Post-Soviet Context

STOCKHOLM STUDIES IN POLITICS 129 Islamic Activism in Azerbaijan: Repression and Mobilization in a Post-Soviet Context Islamic Activism in Azerbaijan Repression and Mobilization in a Post-Soviet Context Sofie Bedford ©Sofie Bedford, Stockholm 2009 Stockholm Studies in Politics 129 ISSN 0346-6620 ISBN 978-91-7155-800-8 (Stockholm University) Södertörn Doctoral Dissertations 33 ISSN 1652-7399 Södertörn Political Studies 6 ISSN 1653-8269 ISBN 978-91-89315-96-9 (Södertörns högskola) Printed in Sweden by Universitetsservice US-AB, Stockholm 2009 Distributor: Department of Political Science, Stockholm University Cover: “Juma mosque in Baku behind bars”, Deyerler 2 2004. Reprinted with the kind permission of Ilgar Ibrahimoglu. Acknowledgements It is quite amazing how much life depends on coincidences. Upon graduating from university I wanted to do an internship with an international organiza- tion in Russia or Ukraine but instead ended up in Baku, Azerbaijan. That turned out to be a stroke of luck as I fell in love with the country and its peo- ple. When I later got the possibility to do a PhD I was determined to find a topic that would bring me back. I did, and now after many years of some- times seemingly never-ending thesis work the project is finally over. A whole lot of people have been important in making this possible, but I would like to start by thanking Anar Ahmadov who helped me a lot more than he realizes. It was after our first conversation over a cup of coffee, where he told me about the growing religiosity he observed in the country, that I un- derstood that studying Islamic mobilization in Azerbaijan would actually be feasible.