Getting Even with Heisenberg$

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bringing out the Dead Alison Abbott Reviews the Story of How a DNA Forensics Team Cracked a Grisly Puzzle

BOOKS & ARTS COMMENT DADO RUVIC/REUTERS/CORBIS DADO A forensics specialist from the International Commission on Missing Persons examines human remains from a mass grave in Tomašica, Bosnia and Herzegovina. FORENSIC SCIENCE Bringing out the dead Alison Abbott reviews the story of how a DNA forensics team cracked a grisly puzzle. uring nine sweltering days in July Bosnia’s Million Bones tells the story of how locating, storing, pre- 1995, Bosnian Serb soldiers slaugh- innovative DNA forensic science solved the paring and analysing tered about 7,000 Muslim men and grisly conundrum of identifying each bone the million or more Dboys from Srebrenica in Bosnia. They took so that grieving families might find some bones. It was in large them to several different locations and shot closure. part possible because them, or blew them up with hand grenades. This is an important book: it illustrates the during those fate- They then scooped up the bodies with bull- unspeakable horrors of a complex war whose ful days in July 1995, dozers and heavy earth-moving equipment, causes have always been hard for outsiders to aerial reconnais- and dumped them into mass graves. comprehend. The author, a British journalist, sance missions by the Bosnia’s Million It was the single most inhuman massacre has the advantage of on-the-ground knowl- Bones: Solving the United States and the of the Bosnian war, which erupted after the edge of the war and of the International World’s Greatest North Atlantic Treaty break-up of Yugoslavia and lasted from 1992 Commission on Missing Persons (ICMP), an Forensic Puzzle Organization had to 1995, leaving some 100,000 dead. -

Der Mythos Der Deutschen Atombombe

Langsame oder schnelle Neutronen? Der Mythos der deutschen Atombombe Prof. Dr. Manfred Popp Karlsruher Institut für Technologie Ringvorlesung zum Gedächtnis an Lise Meitner Freie Universität Berlin 29. Oktober 2018 In diesem Beitrag geht es zwar um Arbeiten zur Kernphysik in Deutschland während des 2.Weltkrieges, an denen Lise Meitner wegen ihrer Emigration 1938 nicht teilnahm. Es geht aber um das Thema Kernspaltung, zu dessen Verständnis sie wesentliches beigetragen hat, um die Arbeit vieler, gut vertrauter, ehemaliger Kollegen und letztlich um das Schicksal der deutschen Physik unter den Nationalsozialisten, die ihre geistige Heimat gewesen war. Da sie nach dem Abwurf der Bombe auf Hiroshima auch als „Mutter der Atombombe“ diffamiert wurde, ist es ihr gewiss nicht gleichgültig gewesen, wie ihr langjähriger Partner und Freund Otto Hahn und seine Kollegen während des Krieges mit dem Problem der möglichen Atombombe umgegangen sind. 1. Stand der Geschichtsschreibung Die Geschichtsschreibung über das deutsche Uranprojekt 1939-1945 ist eine Domäne amerikanischer und britischer Historiker. Für die deutschen Geschichtsforscher hatte eines der wenigen im Ergebnis harmlosen Kapitel der Geschichte des 3. Reiches keine Priorität. Unter den alliierten Historikern hat sich Mark Walker seit seiner Dissertation1 durchgesetzt. Sein Beitrag zur Geschichte der Kaiser Wilhelm-Gesellschaft im 3. Reich beginnt mit den Worten: „The Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Physics is best known as the place where Werner Heisenberg worked on nuclear weapons for Hitler.“2 Im Jahr 2016 habe ich zum ersten Mal belegt, dass diese Schlussfolgerung auf Fehlinterpretationen der Dokumente und auf dem Ignorieren physikalischer Fakten beruht.3 Seit Walker gilt: Nicht an fehlenden Kenntnissen sei die deutsche Atombombe gescheitert, sondern nur an den ökonomischen Engpässen der deutschen Kriegswirtschaft: „An eine Bombenentwicklung wäre [...] auch bei voller Unterstützung des Regimes nicht zu denken gewesen. -

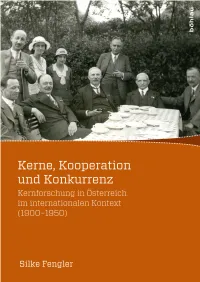

Kerne, Kooperation Und Konkurrenz. Kernforschung In

Wissenschaft, Macht und Kultur in der modernen Geschichte Herausgegeben von Mitchell G. Ash und Carola Sachse Band 3 Silke Fengler Kerne, Kooperation und Konkurrenz Kernforschung in Österreich im internationalen Kontext (1900–1950) 2014 Böhlau Verlag Wien Köln Weimar The research was funded by the Austrian Science Fund (FWF) : P 19557-G08 Bibliografische Information der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek: Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek verzeichnet diese Publikation in der Deutschen Nationalbibliografie; detaillierte bibliografische Datensind im Internet über http://dnb.d-nb.de abrufbar. Umschlagabbildung: Zusammentreffen in Hohenholte bei Münster am 18. Mai 1932 anlässlich der 37. Hauptversammlung der deutschen Bunsengesellschaft für angewandte physikalische Chemie in Münster (16. bis 19. Mai 1932). Von links nach rechts: James Chadwick, Georg von Hevesy, Hans Geiger, Lili Geiger, Lise Meitner, Ernest Rutherford, Otto Hahn, Stefan Meyer, Karl Przibram. © Österreichische Zentralbibliothek für Physik, Wien © 2014 by Böhlau Verlag Ges.m.b.H & Co. KG, Wien Köln Weimar Wiesingerstraße 1, A-1010 Wien, www.boehlau-verlag.com Alle Rechte vorbehalten. Dieses Werk ist urheberrechtlich geschützt. Jede Verwertung außerhalb der engen Grenzen des Urheberrechtsgesetzes ist unzulässig. Lektorat: Ina Heumann Korrektorat: Michael Supanz Umschlaggestaltung: Michael Haderer, Wien Satz: Michael Rauscher, Wien Druck und Bindung: Prime Rate kft., Budapest Gedruckt auf chlor- und säurefrei gebleichtem Papier Printed in Hungary ISBN 978-3-205-79512-4 Inhalt 1. Kernforschung in Österreich im Spannungsfeld von internationaler Kooperation und Konkurrenz ....................... 9 1.1 Internationalisierungsprozesse in der Radioaktivitäts- und Kernforschung : Eine Skizze ...................... 9 1.2 Begriffsklärung und Fragestellungen ................. 10 1.2.2 Ressourcenausstattung und Ressourcenverteilung ......... 12 1.2.3 Zentrum und Peripherie ..................... 14 1.3 Forschungsstand ........................... 16 1.4 Quellenlage ............................. -

Max Planck Institute for the History of Science Werner Heisenberg And

MAX-PLANCK-INSTITUT FÜR WISSENSCHAFTSGESCHICHTE Max Planck Institute for the History of Science PREPRINT 203 (2002) Horst Kant Werner Heisenberg and the German Uranium Project Otto Hahn and the Declarations of Mainau and Göttingen Werner Heisenberg and the German Uranium Project* Horst Kant Werner Heisenberg’s (1901-1976) involvement in the German Uranium Project is the most con- troversial aspect of his life. The controversial discussions on it go from whether Germany at all wanted to built an atomic weapon or only an energy supplying machine (the last only for civil purposes or also for military use for instance in submarines), whether the scientists wanted to support or to thwart such efforts, whether Heisenberg and the others did really understand the mechanisms of an atomic bomb or not, and so on. Examples for both extreme positions in this controversy represent the books by Thomas Powers Heisenberg’s War. The Secret History of the German Bomb,1 who builds up him to a resistance fighter, and by Paul L. Rose Heisenberg and the Nazi Atomic Bomb Project – A Study in German Culture,2 who characterizes him as a liar, fool and with respect to the bomb as a poor scientist; both books were published in the 1990s. In the first part of my paper I will sum up the main facts, known on the German Uranium Project, and in the second part I will discuss some aspects of the role of Heisenberg and other German scientists, involved in this project. Although there is already written a lot on the German Uranium Project – and the best overview up to now supplies Mark Walker with his book German National Socialism and the quest for nuclear power, which was published in * Paper presented on a conference in Moscow (November 13/14, 2001) at the Institute for the History of Science and Technology [àÌÒÚËÚÛÚ ËÒÚÓËË ÂÒÚÂÒÚ‚ÓÁ̇ÌËfl Ë ÚÂıÌËÍË ËÏ. -

Heisenberg and the Nazi Atomic Bomb Project, 1939-1945: a Study in German Culture

Heisenberg and the Nazi Atomic Bomb Project http://content.cdlib.org/xtf/view?docId=ft838nb56t&chunk.id=0&doc.v... Preferred Citation: Rose, Paul Lawrence. Heisenberg and the Nazi Atomic Bomb Project, 1939-1945: A Study in German Culture. Berkeley: University of California Press, c1998 1998. http://ark.cdlib.org/ark:/13030/ft838nb56t/ Heisenberg and the Nazi Atomic Bomb Project A Study in German Culture Paul Lawrence Rose UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PRESS Berkeley · Los Angeles · Oxford © 1998 The Regents of the University of California In affectionate memory of Brian Dalton (1924–1996), Scholar, gentleman, leader, friend And in honor of my father's 80th birthday Preferred Citation: Rose, Paul Lawrence. Heisenberg and the Nazi Atomic Bomb Project, 1939-1945: A Study in German Culture. Berkeley: University of California Press, c1998 1998. http://ark.cdlib.org/ark:/13030/ft838nb56t/ In affectionate memory of Brian Dalton (1924–1996), Scholar, gentleman, leader, friend And in honor of my father's 80th birthday ― ix ― ACKNOWLEDGMENTS For hospitality during various phases of work on this book I am grateful to Aryeh Dvoretzky, Director of the Institute of Advanced Studies of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, whose invitation there allowed me to begin work on the book while on sabbatical leave from James Cook University of North Queensland, Australia, in 1983; and to those colleagues whose good offices made it possible for me to resume research on the subject while a visiting professor at York University and the University of Toronto, Canada, in 1990–92. Grants from the College of the Liberal Arts and the Institute for the Arts and Humanistic Studies of The Pennsylvania State University enabled me to complete the research and writing of the book. -

ABSTRACT Title of Dissertation: the PRINCIPAL UNCERTAINTY: U.S

ABSTRACT Title of Dissertation: THE PRINCIPAL UNCERTAINTY: U.S. ATOMIC INTELLIGENCE, 1942-1949 Vincent Jonathan Houghton, Doctor of Philosophy, 2013 Dissertation directed by: Professor Jon T. Sumida Department of History The subject of this dissertation is the U. S. atomic intelligence effort against both Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union in the period 1942-1949. Both of these intelligence efforts operated within the framework of an entirely new field of intelligence: scientific intelligence. Because of the atomic bomb, for the first time in history a nation’s scientific resources – the abilities of its scientists, the state of its research institutions and laboratories, its scientific educational system – became a key consideration in assessing a potential national security threat. Considering how successfully the United States conducted the atomic intelligence effort against the Germans in the Second World War, why was the United States Government unable to create an effective atomic intelligence apparatus to monitor Soviet scientific and nuclear capabilities? Put another way, why did the effort against the Soviet Union fail so badly, so completely, in all potential metrics – collection, analysis, and dissemination? In addition, did the general assessment of German and Soviet science lead to particular assumptions about their abilities to produce nuclear weapons? How did this assessment affect American presuppositions regarding the German and Soviet strategic threats? Despite extensive historical work on atomic intelligence, the current historiography has not adequately addressed these questions. THE PRINCIPAL UNCERTAINTY: U.S. ATOMIC INTELLIGENCE, 1942-1949 By Vincent Jonathan Houghton Dissertation submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Maryland, College Park, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2013 Advisory Committee: Professor Jon T. -

Hitler's Uranium Club, the Secret Recordings at Farm Hall

HITLER’S URANIUM CLUB DER FARMHALLER NOBELPREIS-SONG (Melodie: Studio of seiner Reis) Detained since more than half a year Ein jeder weiss, das Unglueck kam Sind Hahn und wir in Farm Hall hier. Infolge splitting von Uran, Und fragt man wer is Schuld daran Und fragt man, wer ist Schuld daran, So ist die Antwort: Otto Hahn. So ist die Antwort: Otto Hahn. The real reason nebenbei Die energy macht alles waermer. Ist weil we worked on nuclei. Only die Schweden werden aermer. Und fragt man, wer ist Schuld daran, Und fragt man, wer ist Schuld daran, So ist die Antwort: Otto Hahn. So ist die Antwort: Otto Hahn. Die nuclei waren fuer den Krieg Auf akademisches Geheiss Und fuer den allgemeinen Sieg. Kriegt Deutschland einen Nobel-Preis. Und fragt man, wer ist Schuld daran, Und fragt man, wer ist Schuld daran, So ist die Antwort: Otto Hahn. So ist die Antwort: Otto Hahn. Wie ist das moeglich, fragt man sich, In Oxford Street, da lebt ein Wesen, The story seems wunderlich. Die wird das heut’ mit Thraenen lesen. Und fragt man, wer ist Schuld daran Und fragt man, wer ist Schuld daran, So ist die Antwort: Otto Hahn. So ist die Antwort: Otto Hahn. Die Feldherrn, Staatschefs, Zeitungsknaben, Es fehlte damals nur ein atom, Ihn everyday im Munde haben. Haett er gesagt: I marry you madam. Und fragt man, wer ist Schuld daran, Und fragt man, wer ist Schuld daran, So ist die Antwort: Otto Hahn. So ist die Antwort: Otto Hahn. Even the sweethearts in the world(s) Dies ist nur unsre-erste Feier, Sie nennen sich jetzt: “Atom-girls.” Ich glaub die Sache wird noch teuer, Und fragt man, wer ist Schuld daran, Und fragt man, wer ist Schuld daran, So ist die Antwort: Otto Hahn. -

Churchill Was Not As Short Sighted As Hitler and Saw the Danger Of

Britain and the atomic bomb: MAUD to Nagasaki. Item Type Thesis Authors Gorman, Claire L. Rights <a rel="license" href="http://creativecommons.org/licenses/ by-nc-nd/3.0/"><img alt="Creative Commons License" style="border-width:0" src="http://i.creativecommons.org/l/by- nc-nd/3.0/88x31.png" /></a><br />The University of Bradford theses are licenced under a <a rel="license" href="http:// creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/">Creative Commons Licence</a>. Download date 25/09/2021 12:38:38 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10454/4332 Chapter Three: The Allies and the bomb, August 1943 to August 1945 1. Germany Churchill realised a German nuclear weapon could threaten London. If Germany had a nuclear reactor it would be possible to launch a radioactive strike on the British capital. Accordingly, the British planned an audacious raid on the German heavy water supply in Norway. An attack squad was parachuted into the Norsk Hydro plant on 16th February 1943. This attack was „completely successful.‟1 The attack party planted explosives in the factory, causing extensive damage „and over 4 months‟ stock of “heavy water” were destroyed.‟2 Later that year, the British were dismayed to learn via the Norwegian underground that the Norsk Hydro plant had not in fact been put out of action. By August 1943 it had resumed production. The fact that the Germans had rebuilt the High Concentration Plant so rapidly was taken by the Allies as „a clear indication that the uranium project had a high priority in the German war effort.‟3 John Anderson decided prompt action was essential and the plant should be attacked once again. -

Nazi Secret Weapons and the Cold War Allied Legend

Nazi Secret Weapons and the Cold War Allied Legend http://myth.greyfalcon.us/sun.htm by Joseph P. Farrell GÖTTERDÄMMERUNG "A comprehensive February 1942 (German) Army Ordnance report on the German uranium enrichment program includes the statement that the critical mass of a nuclear weapon lay between 10 and 100 kilograms of either uranium 235 or element 94.... In fact the German estimate of critical mass of 10 to 100 kilograms was comparable to the contemporary Allied estimate of 2 to 100.... The German scientists working on uranium neither withheld their figure for critical mass because of moral scruples nor did they provide an inaccurate estimate as the result of gross scientific error." --Mark Walker, "Nazi Science: Myth, Truth, and the German Atomic Bomb" A Badly Written Finale "In southern Germany, meanwhile, the American Third and Seventh and the French First Armies had been driving steadily eastward into the so-called 'National Redoubt'.... The American Third Army drove on into Czechoslovakia and by May 6 had captured Pilsen and Karlsbad and was approaching Prague." --F. Lee Benns, "Europe Since 1914 In Its World Setting" (New York: F.S. Crofts and Co., 1946) On a night in October 1944, a German pilot and rocket expert by the same of Hans Zinsser was flying his Heinkel 111 twin-engine bomber in twilight over northern Germany, close to the Baltic coast in the province of Mecklenburg. He was flying at twilight to avoid the Allied fighter aircraft that at that time had all but undisputed mastery of the skies over Germany. Little did he know that what he saw that night would be locked in the vaults of the highest classification of the United States government for several decades after the war. -

The Virus House -

David Irving The Virus House - F FOCAL POINT Copyright © by David Irving Electronic version copyright © by Parforce UK Ltd. All rights reserved No reproduction, copy or transmission of this publication may be made without written permission. Copies may be downloaded from our website for research purposes only. No part of this publication may be commercially reproduced, copied, or transmitted save with written permission in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright Act (as amended). Any person who does any unauthorised act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages. To Pilar is the son of a Royal Navy commander. Imper- fectly educated at London’s Imperial College of Science & Tech- nology and at University College, he subsequently spent a year in Germany working in a steel mill and perfecting his fluency in the language. In he published The Destruction of Dresden. This became a best-seller in many countries. Among his thirty books (including three in German), the best-known include Hitler’s War; The Trail of the Fox: The Life of Field Marshal Rommel; Accident, the Death of General Sikorski; The Rise and Fall of the Luftwaffe; Göring: a Biography; and Nuremberg, the Last Battle. The second volume of Churchill's War appeared in and he is now completing the third. His works are available as free downloads at www.fpp.co.uk/books. Contents Author’s Introduction ............................. Solstice.......................................................... A Letter to the War Office ........................ The Plutonium Alternative....................... An Error of Consequence ......................... Item Sixteen on a Long Agenda............... Freshman................................................... Vemork Attacked..................................... -

Bruno Touschek in Germany After the War: 1945-46

LABORATORI NAZIONALI DI FRASCATI INFN–19-17/LNF October 10, 2019 MIT-CTP/5150 Bruno Touschek in Germany after the War: 1945-46 Luisa Bonolis1, Giulia Pancheri2;† 1)Max Planck Institute for the History of Science, Boltzmannstraße 22, 14195 Berlin, Germany 2)INFN, Laboratori Nazionali di Frascati, P.O. Box 13, I-00044 Frascati, Italy Abstract Bruno Touschek was an Austrian born theoretical physicist, who proposed and built the first electron-positron collider in 1960 in the Frascati National Laboratories in Italy. In this note we reconstruct a crucial period of Bruno Touschek’s life so far scarcely explored, which runs from Summer 1945 to the end of 1946. We shall describe his university studies in Gottingen,¨ placing them in the context of the reconstruction of German science after 1945. The influence of Werner Heisenberg and other prominent German physicists will be highlighted. In parallel, we shall show how the decisions of the Allied powers, towards restructuring science and technology in the UK after the war effort, determined Touschek’s move to the University of Glasgow in 1947. Make it a story of distances and starlight Robert Penn Warren, 1905-1989, c 1985 Robert Penn Warren arXiv:1910.09075v1 [physics.hist-ph] 20 Oct 2019 e-mail: [email protected], [email protected]. Authors’ ordering in this and related works alternates to reflect that this work is part of a joint collaboration project with no principal author. †) Also at Center for Theoretical Physics, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, USA. Contents 1 Introduction2 2 Hamburg 1945: from death rays to post-war science4 3 German science and the mission of the T-force6 3.1 Operation Epsilon . -

Nazi Nuclear Research: Why Didn’T Hitler Get the Bomb? Jim Thomson

Nazi nuclear research: Why didn’t Hitler get the Bomb? Jim Thomson www.safetyinengineering.com 1 Nazi nuclear research 1. The German project and a brief comparison with the Manhattan and V-weapons projects 2. German project technical achievements and failures 3. Political and organisational factors 4. Motives, ethics, competence and honesty 5. Postscript: The lunatic fringes 2 Jim Thomson www.safetyinengineering.com 1. The German project and a brief comparison with the Manhattan and V-weapons projects 3 Jim Thomson www.safetyinengineering.com Arnold Kramish 1985 The Griffin 1947: April 1943: “Los ALSOS – Samuel Mark Walker 1989 German National Socialism and the Quest Dec 1942: for Nuclear Power 1939–1949 Alamos Primer” Goudsmit Chicago pile UK Government 1992 Farm Hall transcripts declassified lecture notes give (republished 1996) critical complete overview of David Cassidy 1992 Uncertainty: The Life and Science of Werner Heisenberg bomb project Frisch-Peierls 1944/1945: ALSOS 1956: Thomas Powers 1993 Heisenberg’s War memorandum mission to capture Brighter Than a Mark Walker 1995 Nazi Science: Myth, Truth, and the German March 1940 German researchers , Thousand Suns – Atomic Bomb July/Aug 1945: Einstein letter equipment and data Robert Jungk Paul Lawrence 1998 Heisenberg and the Nazi Atomic Bomb to Roosevelt Trinity, Little Boy and Rose Project: A Study in German Culture Fat Man. The Smyth 1968: Hans Bethe 2000 ‘The German Uranium Project’, Article in August 1939 Physics Today Report outlines the The Virus House - Jeremy Bernstein 2001