Overhearing Heisenberg

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bringing out the Dead Alison Abbott Reviews the Story of How a DNA Forensics Team Cracked a Grisly Puzzle

BOOKS & ARTS COMMENT DADO RUVIC/REUTERS/CORBIS DADO A forensics specialist from the International Commission on Missing Persons examines human remains from a mass grave in Tomašica, Bosnia and Herzegovina. FORENSIC SCIENCE Bringing out the dead Alison Abbott reviews the story of how a DNA forensics team cracked a grisly puzzle. uring nine sweltering days in July Bosnia’s Million Bones tells the story of how locating, storing, pre- 1995, Bosnian Serb soldiers slaugh- innovative DNA forensic science solved the paring and analysing tered about 7,000 Muslim men and grisly conundrum of identifying each bone the million or more Dboys from Srebrenica in Bosnia. They took so that grieving families might find some bones. It was in large them to several different locations and shot closure. part possible because them, or blew them up with hand grenades. This is an important book: it illustrates the during those fate- They then scooped up the bodies with bull- unspeakable horrors of a complex war whose ful days in July 1995, dozers and heavy earth-moving equipment, causes have always been hard for outsiders to aerial reconnais- and dumped them into mass graves. comprehend. The author, a British journalist, sance missions by the Bosnia’s Million It was the single most inhuman massacre has the advantage of on-the-ground knowl- Bones: Solving the United States and the of the Bosnian war, which erupted after the edge of the war and of the International World’s Greatest North Atlantic Treaty break-up of Yugoslavia and lasted from 1992 Commission on Missing Persons (ICMP), an Forensic Puzzle Organization had to 1995, leaving some 100,000 dead. -

Nobel Prize Physicists Meet at Lindau

From 28 June to 2 July 1971 the German island town of Lindau in Nobel Prize Physicists Lake Constance close to the Austrian and Swiss borders was host to a gathering of illustrious men of meet at Lindau science when, for the 21st time, Nobel Laureates held their reunion there. The success of the first Lindau reunion (1951) of Nobel Prize win ners in medicine had inspired the organizers to invite the chemists and W. S. Newman the physicists in turn in subsequent years. After the first three-year cycle the United Kingdom, and an audience the dates of historical events. These it was decided to let students and of more than 500 from 8 countries deviations in the radiocarbon time young scientists also attend the daily filled the elegant Stadttheater. scale are due to changes in incident meetings so they could encounter The programme consisted of a num cosmic radiation (producing the these eminent men on an informal ber of lectures in the mornings, two carbon isotopes) brought about by and personal level. For the Nobel social functions, a platform dis variations in the geomagnetic field. Laureates too the Lindau gatherings cussion, an informal reunion between Thus chemistry may reveal man soon became an agreeable occasion students and Nobel Laureates and, kind’s remote past whereas its long for making or renewing acquain on the last day, the traditional term future could well be shaped by tances with their contemporaries, un steamer excursion on Lake Cons the developments mentioned by trammelled by the formalities of the tance to the island of Mainau belong Mössbauer, viz. -

Der Mythos Der Deutschen Atombombe

Langsame oder schnelle Neutronen? Der Mythos der deutschen Atombombe Prof. Dr. Manfred Popp Karlsruher Institut für Technologie Ringvorlesung zum Gedächtnis an Lise Meitner Freie Universität Berlin 29. Oktober 2018 In diesem Beitrag geht es zwar um Arbeiten zur Kernphysik in Deutschland während des 2.Weltkrieges, an denen Lise Meitner wegen ihrer Emigration 1938 nicht teilnahm. Es geht aber um das Thema Kernspaltung, zu dessen Verständnis sie wesentliches beigetragen hat, um die Arbeit vieler, gut vertrauter, ehemaliger Kollegen und letztlich um das Schicksal der deutschen Physik unter den Nationalsozialisten, die ihre geistige Heimat gewesen war. Da sie nach dem Abwurf der Bombe auf Hiroshima auch als „Mutter der Atombombe“ diffamiert wurde, ist es ihr gewiss nicht gleichgültig gewesen, wie ihr langjähriger Partner und Freund Otto Hahn und seine Kollegen während des Krieges mit dem Problem der möglichen Atombombe umgegangen sind. 1. Stand der Geschichtsschreibung Die Geschichtsschreibung über das deutsche Uranprojekt 1939-1945 ist eine Domäne amerikanischer und britischer Historiker. Für die deutschen Geschichtsforscher hatte eines der wenigen im Ergebnis harmlosen Kapitel der Geschichte des 3. Reiches keine Priorität. Unter den alliierten Historikern hat sich Mark Walker seit seiner Dissertation1 durchgesetzt. Sein Beitrag zur Geschichte der Kaiser Wilhelm-Gesellschaft im 3. Reich beginnt mit den Worten: „The Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Physics is best known as the place where Werner Heisenberg worked on nuclear weapons for Hitler.“2 Im Jahr 2016 habe ich zum ersten Mal belegt, dass diese Schlussfolgerung auf Fehlinterpretationen der Dokumente und auf dem Ignorieren physikalischer Fakten beruht.3 Seit Walker gilt: Nicht an fehlenden Kenntnissen sei die deutsche Atombombe gescheitert, sondern nur an den ökonomischen Engpässen der deutschen Kriegswirtschaft: „An eine Bombenentwicklung wäre [...] auch bei voller Unterstützung des Regimes nicht zu denken gewesen. -

Heisenberg's Visit to Niels Bohr in 1941 and the Bohr Letters

Klaus Gottstein Max-Planck-Institut für Physik (Werner-Heisenberg-Institut) Föhringer Ring 6 D-80805 Munich, Germany 26 February, 2002 New insights? Heisenberg’s visit to Niels Bohr in 1941 and the Bohr letters1 The documents recently released by the Niels Bohr Archive do not, in an unambiguous way, solve the enigma of what happened during the critical brief discussion between Bohr and Heisenberg in 1941 which so upset Bohr and made Heisenberg so desperate. But they are interesting, they show what Bohr remembered 15 years later. What Heisenberg remembered was already described by him in his memoirs “Der Teil und das Ganze”. The two descriptions are complementary, they are not incompatible. The two famous physicists, as Hans Bethe called it recently, just talked past each other, starting from different assumptions. They did not finish their conversation. Bohr broke it off before Heisenberg had a chance to complete his intended mission. Heisenberg and Bohr had not seen each other since the beginning of the war in 1939. In the meantime, Heisenberg and some other German physicists had been drafted by Army Ordnance to explore the feasibility of a nuclear bomb which, after the discovery of fission and of the chain reaction, could not be ruled out. How real was this theoretical possibility? By 1941 Heisenberg, after two years of intense theoretical and experimental investigations by the drafted group known as the “Uranium Club”, had reached the conclusion that the construction of a nuclear bomb would be feasible in principle, but technically and economically very difficult. He knew in principle how it could be done, by Uranium isotope separation or by Plutonium production in reactors, but both ways would take many years and would be beyond the means of Germany in time of war, and probably also beyond the means of Germany’s adversaries. -

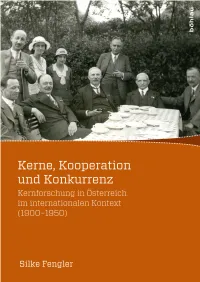

Kerne, Kooperation Und Konkurrenz. Kernforschung In

Wissenschaft, Macht und Kultur in der modernen Geschichte Herausgegeben von Mitchell G. Ash und Carola Sachse Band 3 Silke Fengler Kerne, Kooperation und Konkurrenz Kernforschung in Österreich im internationalen Kontext (1900–1950) 2014 Böhlau Verlag Wien Köln Weimar The research was funded by the Austrian Science Fund (FWF) : P 19557-G08 Bibliografische Information der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek: Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek verzeichnet diese Publikation in der Deutschen Nationalbibliografie; detaillierte bibliografische Datensind im Internet über http://dnb.d-nb.de abrufbar. Umschlagabbildung: Zusammentreffen in Hohenholte bei Münster am 18. Mai 1932 anlässlich der 37. Hauptversammlung der deutschen Bunsengesellschaft für angewandte physikalische Chemie in Münster (16. bis 19. Mai 1932). Von links nach rechts: James Chadwick, Georg von Hevesy, Hans Geiger, Lili Geiger, Lise Meitner, Ernest Rutherford, Otto Hahn, Stefan Meyer, Karl Przibram. © Österreichische Zentralbibliothek für Physik, Wien © 2014 by Böhlau Verlag Ges.m.b.H & Co. KG, Wien Köln Weimar Wiesingerstraße 1, A-1010 Wien, www.boehlau-verlag.com Alle Rechte vorbehalten. Dieses Werk ist urheberrechtlich geschützt. Jede Verwertung außerhalb der engen Grenzen des Urheberrechtsgesetzes ist unzulässig. Lektorat: Ina Heumann Korrektorat: Michael Supanz Umschlaggestaltung: Michael Haderer, Wien Satz: Michael Rauscher, Wien Druck und Bindung: Prime Rate kft., Budapest Gedruckt auf chlor- und säurefrei gebleichtem Papier Printed in Hungary ISBN 978-3-205-79512-4 Inhalt 1. Kernforschung in Österreich im Spannungsfeld von internationaler Kooperation und Konkurrenz ....................... 9 1.1 Internationalisierungsprozesse in der Radioaktivitäts- und Kernforschung : Eine Skizze ...................... 9 1.2 Begriffsklärung und Fragestellungen ................. 10 1.2.2 Ressourcenausstattung und Ressourcenverteilung ......... 12 1.2.3 Zentrum und Peripherie ..................... 14 1.3 Forschungsstand ........................... 16 1.4 Quellenlage ............................. -

Max Planck Institute for the History of Science Werner Heisenberg And

MAX-PLANCK-INSTITUT FÜR WISSENSCHAFTSGESCHICHTE Max Planck Institute for the History of Science PREPRINT 203 (2002) Horst Kant Werner Heisenberg and the German Uranium Project Otto Hahn and the Declarations of Mainau and Göttingen Werner Heisenberg and the German Uranium Project* Horst Kant Werner Heisenberg’s (1901-1976) involvement in the German Uranium Project is the most con- troversial aspect of his life. The controversial discussions on it go from whether Germany at all wanted to built an atomic weapon or only an energy supplying machine (the last only for civil purposes or also for military use for instance in submarines), whether the scientists wanted to support or to thwart such efforts, whether Heisenberg and the others did really understand the mechanisms of an atomic bomb or not, and so on. Examples for both extreme positions in this controversy represent the books by Thomas Powers Heisenberg’s War. The Secret History of the German Bomb,1 who builds up him to a resistance fighter, and by Paul L. Rose Heisenberg and the Nazi Atomic Bomb Project – A Study in German Culture,2 who characterizes him as a liar, fool and with respect to the bomb as a poor scientist; both books were published in the 1990s. In the first part of my paper I will sum up the main facts, known on the German Uranium Project, and in the second part I will discuss some aspects of the role of Heisenberg and other German scientists, involved in this project. Although there is already written a lot on the German Uranium Project – and the best overview up to now supplies Mark Walker with his book German National Socialism and the quest for nuclear power, which was published in * Paper presented on a conference in Moscow (November 13/14, 2001) at the Institute for the History of Science and Technology [àÌÒÚËÚÛÚ ËÒÚÓËË ÂÒÚÂÒÚ‚ÓÁ̇ÌËfl Ë ÚÂıÌËÍË ËÏ. -

Heisenberg and the Nazi Atomic Bomb Project, 1939-1945: a Study in German Culture

Heisenberg and the Nazi Atomic Bomb Project http://content.cdlib.org/xtf/view?docId=ft838nb56t&chunk.id=0&doc.v... Preferred Citation: Rose, Paul Lawrence. Heisenberg and the Nazi Atomic Bomb Project, 1939-1945: A Study in German Culture. Berkeley: University of California Press, c1998 1998. http://ark.cdlib.org/ark:/13030/ft838nb56t/ Heisenberg and the Nazi Atomic Bomb Project A Study in German Culture Paul Lawrence Rose UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PRESS Berkeley · Los Angeles · Oxford © 1998 The Regents of the University of California In affectionate memory of Brian Dalton (1924–1996), Scholar, gentleman, leader, friend And in honor of my father's 80th birthday Preferred Citation: Rose, Paul Lawrence. Heisenberg and the Nazi Atomic Bomb Project, 1939-1945: A Study in German Culture. Berkeley: University of California Press, c1998 1998. http://ark.cdlib.org/ark:/13030/ft838nb56t/ In affectionate memory of Brian Dalton (1924–1996), Scholar, gentleman, leader, friend And in honor of my father's 80th birthday ― ix ― ACKNOWLEDGMENTS For hospitality during various phases of work on this book I am grateful to Aryeh Dvoretzky, Director of the Institute of Advanced Studies of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, whose invitation there allowed me to begin work on the book while on sabbatical leave from James Cook University of North Queensland, Australia, in 1983; and to those colleagues whose good offices made it possible for me to resume research on the subject while a visiting professor at York University and the University of Toronto, Canada, in 1990–92. Grants from the College of the Liberal Arts and the Institute for the Arts and Humanistic Studies of The Pennsylvania State University enabled me to complete the research and writing of the book. -

ABSTRACT Title of Dissertation: the PRINCIPAL UNCERTAINTY: U.S

ABSTRACT Title of Dissertation: THE PRINCIPAL UNCERTAINTY: U.S. ATOMIC INTELLIGENCE, 1942-1949 Vincent Jonathan Houghton, Doctor of Philosophy, 2013 Dissertation directed by: Professor Jon T. Sumida Department of History The subject of this dissertation is the U. S. atomic intelligence effort against both Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union in the period 1942-1949. Both of these intelligence efforts operated within the framework of an entirely new field of intelligence: scientific intelligence. Because of the atomic bomb, for the first time in history a nation’s scientific resources – the abilities of its scientists, the state of its research institutions and laboratories, its scientific educational system – became a key consideration in assessing a potential national security threat. Considering how successfully the United States conducted the atomic intelligence effort against the Germans in the Second World War, why was the United States Government unable to create an effective atomic intelligence apparatus to monitor Soviet scientific and nuclear capabilities? Put another way, why did the effort against the Soviet Union fail so badly, so completely, in all potential metrics – collection, analysis, and dissemination? In addition, did the general assessment of German and Soviet science lead to particular assumptions about their abilities to produce nuclear weapons? How did this assessment affect American presuppositions regarding the German and Soviet strategic threats? Despite extensive historical work on atomic intelligence, the current historiography has not adequately addressed these questions. THE PRINCIPAL UNCERTAINTY: U.S. ATOMIC INTELLIGENCE, 1942-1949 By Vincent Jonathan Houghton Dissertation submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Maryland, College Park, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2013 Advisory Committee: Professor Jon T. -

Hitler's Uranium Club, the Secret Recordings at Farm Hall

HITLER’S URANIUM CLUB DER FARMHALLER NOBELPREIS-SONG (Melodie: Studio of seiner Reis) Detained since more than half a year Ein jeder weiss, das Unglueck kam Sind Hahn und wir in Farm Hall hier. Infolge splitting von Uran, Und fragt man wer is Schuld daran Und fragt man, wer ist Schuld daran, So ist die Antwort: Otto Hahn. So ist die Antwort: Otto Hahn. The real reason nebenbei Die energy macht alles waermer. Ist weil we worked on nuclei. Only die Schweden werden aermer. Und fragt man, wer ist Schuld daran, Und fragt man, wer ist Schuld daran, So ist die Antwort: Otto Hahn. So ist die Antwort: Otto Hahn. Die nuclei waren fuer den Krieg Auf akademisches Geheiss Und fuer den allgemeinen Sieg. Kriegt Deutschland einen Nobel-Preis. Und fragt man, wer ist Schuld daran, Und fragt man, wer ist Schuld daran, So ist die Antwort: Otto Hahn. So ist die Antwort: Otto Hahn. Wie ist das moeglich, fragt man sich, In Oxford Street, da lebt ein Wesen, The story seems wunderlich. Die wird das heut’ mit Thraenen lesen. Und fragt man, wer ist Schuld daran Und fragt man, wer ist Schuld daran, So ist die Antwort: Otto Hahn. So ist die Antwort: Otto Hahn. Die Feldherrn, Staatschefs, Zeitungsknaben, Es fehlte damals nur ein atom, Ihn everyday im Munde haben. Haett er gesagt: I marry you madam. Und fragt man, wer ist Schuld daran, Und fragt man, wer ist Schuld daran, So ist die Antwort: Otto Hahn. So ist die Antwort: Otto Hahn. Even the sweethearts in the world(s) Dies ist nur unsre-erste Feier, Sie nennen sich jetzt: “Atom-girls.” Ich glaub die Sache wird noch teuer, Und fragt man, wer ist Schuld daran, Und fragt man, wer ist Schuld daran, So ist die Antwort: Otto Hahn. -

Farm Hall Transcripts)

Volume 7. Nazi Germany, 1933-1945 Transcript of Surreptitiously Taped Conversations among German Nuclear Physicists at Farm Hall (August 6-7, 1945) At the beginning of the war, Germany’s leading nuclear physicists were called to the army weapons department. There, as part of the “uranium project” under the direction of Werner Heisenberg, they were charged with determining the extent to which nuclear fission could aid in the war effort. (Nuclear fission had been discovered by Otto Hahn and Lise Meitner in 1938.) Unlike their American colleagues in the Manhattan Project, German physicists did not succeed in building their own nuclear weapon. In June 1942, the researchers informed Albert Speer that they were in no position to build an atomic bomb with the resources at hand in less than 3-5 years, at which point the project was scrapped. After the end of the war, both the Western Allies and the Soviet Union tried to recruit the German scientists for their own purposes. From July 3, 1945, to January 3, 1946, the Allies incarcerated ten German nuclear physicists at the English country estate of Farm Hall, their goal being to obtain information about the German nuclear research project by way of surreptitiously taped conversations. The following transcript includes the scientists’ reactions to reports that America had dropped an atomic bomb on Hiroshima. The scientists also discuss their relationship to the Nazi regime and offer some prognoses for Germany’s future. As the transcript shows, Otto Hahn was especially shaken by the dropping of the bomb; later, he campaigned against the misuse of nuclear energy for military purposes. -

The German Rocket Jet and the Nuclear Programs of World War II Max Lutze Union College - Schenectady, NY

Union College Union | Digital Works Honors Theses Student Work 6-2016 The German Rocket Jet and the Nuclear Programs of World War II Max Lutze Union College - Schenectady, NY Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalworks.union.edu/theses Part of the European History Commons, German Language and Literature Commons, History of Science, Technology, and Medicine Commons, Military History Commons, and the Military, War, and Peace Commons Recommended Citation Lutze, Max, "The German Rocket Jet and the Nuclear Programs of World War II" (2016). Honors Theses. 179. https://digitalworks.union.edu/theses/179 This Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Work at Union | Digital Works. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of Union | Digital Works. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The German Rocket, Jet, and Nuclear Programs of World War II By Max Lutze * * * * * * * * * Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for Honors in the Department of History UNION COLLEGE March, 2016 2 Abstract German military technology in World War II was among the best of the major warring powers and in many cases it was the groundwork for postwar innovations that permanently changed global warfare. Three of the most important projects undertaken, which were not only German initiatives and therefore perhaps among the most valuable programs for both the major Axis and Allied nations, include the rocket, jet, and nuclear programs. In Germany, each of these technologies was given different levels of attention and met with varying degrees of success in their development and application. -

Some Famous Physicists Ing Weyl’S Book Space, Time, Matter, the Same Book That Heisenberg Had Read As a Young Man

Heisenberg’s first graduate student was Felix Bloch. One day, while walking together, they started to discuss the concepts of space and time. Bloch had just finished read- Some Famous Physicists ing Weyl’s book Space, Time, Matter, the same book that Heisenberg had read as a young man. Still very much Anton Z. Capri† under the influence of this scholarly work, Bloch declared that he now understood that space was simply the field of Sometimes we are influenced by teachers in ways that, affine transformations. Heisenberg paused, looked at him, although negative, lead to positive results. This happened and replied, “Nonsense, space is blue and birds fly through to Werner Heisenberg1 and Max Born,2 both of whom it.” started out to be mathematicians, but switched to physics There is another version of why Heisenberg switched to due to encounters with professors. physics. At an age of 19, Heisenberg went to the University As a young student at the University of Munich, Heisen- of G¨ottingen to hear lectures by Niels Bohr.4 These lec- berg wanted to attend the seminar of Professor F. von tures were attended by physicists and their students from Lindemann,3 famous for solving the ancient problem of various universities and were jokingly referred to as “the squaring the circle. Heisenberg had Bohr festival season.” Here, Bohr expounded on his latest read Weyl’s book Space, Time, Matter theories of atomic structure. The young Heisenberg in the and, both excited and disturbed by the audience did not hesitate to ask questions when Bohr’s abstract mathematical arguments, had explanations were less than clear.