Operation Epsilon: Science, History, and Theatrical Narrative

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Development of Military Nuclear Strategy And

The Development of Military Nuclear Strategy and Anglo-American Relations, 1939 – 1958 Submitted by: Geoffrey Charles Mallett Skinner to the University of Exeter as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History, July 2018 This thesis is available for Library use on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. I certify that all material in this thesis which is not my own work has been identified and that no material has previously been submitted and approved for the award of a degree by this or any other University. (Signature) ……………………………………………………………………………… 1 Abstract There was no special governmental partnership between Britain and America during the Second World War in atomic affairs. A recalibration is required that updates and amends the existing historiography in this respect. The wartime atomic relations of those countries were cooperative at the level of science and resources, but rarely that of the state. As soon as it became apparent that fission weaponry would be the main basis of future military power, America decided to gain exclusive control over the weapon. Britain could not replicate American resources and no assistance was offered to it by its conventional ally. America then created its own, closed, nuclear system and well before the 1946 Atomic Energy Act, the event which is typically seen by historians as the explanation of the fracturing of wartime atomic relations. Immediately after 1945 there was insufficient systemic force to create change in the consistent American policy of atomic monopoly. As fusion bombs introduced a new magnitude of risk, and as the nuclear world expanded and deepened, the systemic pressures grew. -

Bringing out the Dead Alison Abbott Reviews the Story of How a DNA Forensics Team Cracked a Grisly Puzzle

BOOKS & ARTS COMMENT DADO RUVIC/REUTERS/CORBIS DADO A forensics specialist from the International Commission on Missing Persons examines human remains from a mass grave in Tomašica, Bosnia and Herzegovina. FORENSIC SCIENCE Bringing out the dead Alison Abbott reviews the story of how a DNA forensics team cracked a grisly puzzle. uring nine sweltering days in July Bosnia’s Million Bones tells the story of how locating, storing, pre- 1995, Bosnian Serb soldiers slaugh- innovative DNA forensic science solved the paring and analysing tered about 7,000 Muslim men and grisly conundrum of identifying each bone the million or more Dboys from Srebrenica in Bosnia. They took so that grieving families might find some bones. It was in large them to several different locations and shot closure. part possible because them, or blew them up with hand grenades. This is an important book: it illustrates the during those fate- They then scooped up the bodies with bull- unspeakable horrors of a complex war whose ful days in July 1995, dozers and heavy earth-moving equipment, causes have always been hard for outsiders to aerial reconnais- and dumped them into mass graves. comprehend. The author, a British journalist, sance missions by the Bosnia’s Million It was the single most inhuman massacre has the advantage of on-the-ground knowl- Bones: Solving the United States and the of the Bosnian war, which erupted after the edge of the war and of the International World’s Greatest North Atlantic Treaty break-up of Yugoslavia and lasted from 1992 Commission on Missing Persons (ICMP), an Forensic Puzzle Organization had to 1995, leaving some 100,000 dead. -

University of Cincinnati

! "# $ % & % ' % !" #$ !% !' &$ &""! '() ' #$ *+ ' "# ' '% $$(' ,) * !$- .*./- 0 #!1- 2 *,*- Atomic Apocalypse – ‘Nuclear Fiction’ in German Literature and Culture A dissertation submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Cincinnati In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTORATE OF PHILOSOPHY (Ph.D.) in the Department of German Studies of the College of Arts and Sciences 2010 by Wolfgang Lueckel B.A. (equivalent) in German Literature, Universität Mainz, 2003 M.A. in German Studies, University of Cincinnati, 2005 Committee Chair: Sara Friedrichsmeyer, Ph.D. Committee Members: Todd Herzog, Ph.D. (second reader) Katharina Gerstenberger, Ph.D. Richard E. Schade, Ph.D. ii Abstract In my dissertation “Atomic Apocalypse – ‘Nuclear Fiction’ in German Literature and Culture,” I investigate the portrayal of the nuclear age and its most dreaded fantasy, the nuclear apocalypse, in German fictionalizations and cultural writings. My selection contains texts of disparate natures and provenance: about fifty plays, novels, audio plays, treatises, narratives, films from 1946 to 2009. I regard these texts as a genre of their own and attempt a description of the various elements that tie them together. The fascination with the end of the world that high and popular culture have developed after 9/11 partially originated from the tradition of nuclear fiction since 1945. The Cold War has produced strong and lasting apocalyptic images in German culture that reject the traditional biblical apocalypse and that draw up a new worldview. In particular, German nuclear fiction sees the atomic apocalypse as another step towards the technical facilitation of genocide, preceded by the Jewish Holocaust with its gas chambers and ovens. -

Plasma Physics in the 20Th Century As Told by Players”

Eur. Phys. J. H 43, 337{353 (2018) https://doi.org/10.1140/epjh/e2018-90061-5 THE EUROPEAN PHYSICAL JOURNAL H Editorial Editorial introduction to the special issue \Plasma physics in the 20th century as told by players" Patrick H. Diamond1,a , Uriel Frisch2, and Yves Pomeau3 1 University of California San Diego, La Jolla, CA 92093-0319, USA 2 Universit´eC^oted'Azur, OCA, Lab. Lagrange, CS 34229, 06304 Nice Cedex 4, France 3 Ladhyx, Ecole´ Polytechnique, Palaiseau, France Received 31 October 2018 Published online 30 November 2018 c EDP Sciences, Springer-Verlag GmbH Germany, part of Springer Nature, 2018 Our ancestors lived in a world where { as far as they were aware { electrons and ions lived happily bound together. But with suitable conditions, e.g. low density and/or high temperature, electrons and ions will unbind and we obtain a plasma, a state of matter of which we became increasingly aware in the 20th century, and which pervades our universe near and far. There are also many applications of plasma physics: chip etching, TV screens, torches, propulsion, fusion (through magnetic or inertial confinement), astrophysics and space physics, and laser physics, to cite just a few. At the crossroads of electrodynamics, continuum physics, kinetic theory and nonlinear physics, plasma physics enjoys an abundance of riches. Actually, so much that we can only cover a fraction of its history in this limited volume. The history of plasma physics presented here covers mostly the period from 1950 to 2000. The issue is focussed both on fundamentals and on applications in controlled fusion through magnetic confinement, which in turn raises a host of fundamental and interesting questions in various areas. -

Der Mythos Der Deutschen Atombombe

Langsame oder schnelle Neutronen? Der Mythos der deutschen Atombombe Prof. Dr. Manfred Popp Karlsruher Institut für Technologie Ringvorlesung zum Gedächtnis an Lise Meitner Freie Universität Berlin 29. Oktober 2018 In diesem Beitrag geht es zwar um Arbeiten zur Kernphysik in Deutschland während des 2.Weltkrieges, an denen Lise Meitner wegen ihrer Emigration 1938 nicht teilnahm. Es geht aber um das Thema Kernspaltung, zu dessen Verständnis sie wesentliches beigetragen hat, um die Arbeit vieler, gut vertrauter, ehemaliger Kollegen und letztlich um das Schicksal der deutschen Physik unter den Nationalsozialisten, die ihre geistige Heimat gewesen war. Da sie nach dem Abwurf der Bombe auf Hiroshima auch als „Mutter der Atombombe“ diffamiert wurde, ist es ihr gewiss nicht gleichgültig gewesen, wie ihr langjähriger Partner und Freund Otto Hahn und seine Kollegen während des Krieges mit dem Problem der möglichen Atombombe umgegangen sind. 1. Stand der Geschichtsschreibung Die Geschichtsschreibung über das deutsche Uranprojekt 1939-1945 ist eine Domäne amerikanischer und britischer Historiker. Für die deutschen Geschichtsforscher hatte eines der wenigen im Ergebnis harmlosen Kapitel der Geschichte des 3. Reiches keine Priorität. Unter den alliierten Historikern hat sich Mark Walker seit seiner Dissertation1 durchgesetzt. Sein Beitrag zur Geschichte der Kaiser Wilhelm-Gesellschaft im 3. Reich beginnt mit den Worten: „The Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Physics is best known as the place where Werner Heisenberg worked on nuclear weapons for Hitler.“2 Im Jahr 2016 habe ich zum ersten Mal belegt, dass diese Schlussfolgerung auf Fehlinterpretationen der Dokumente und auf dem Ignorieren physikalischer Fakten beruht.3 Seit Walker gilt: Nicht an fehlenden Kenntnissen sei die deutsche Atombombe gescheitert, sondern nur an den ökonomischen Engpässen der deutschen Kriegswirtschaft: „An eine Bombenentwicklung wäre [...] auch bei voller Unterstützung des Regimes nicht zu denken gewesen. -

The Beginning of the Nuclear Age the Einstein Szilard Letter to Roosevelt Aug

Questions 1. Otto Hahn received the 1945 Nobel prize for the experimental discovery of fission. His former colleague Lise Meitner, who explained the phenomenon did not. Do you consider that a fair decision of the Nobel prize committee? 2. What is the difference between a radiative capture reaction, a scattering reaction, and a nuclear reaction? 3. The allied bomb war against the civilian population did not bring the anticipated results, instead of weakening the will for resistance it strengthened it since it provided strong propaganda material to the German and Japanese leadership. Why did the bomb raids continue? The Beginning of the Nuclear Age The Einstein Szilard letter to Roosevelt Aug. 2, 1939 "Because of the danger that Hitler might be the first to have the bomb, I signed a letter to the President which had been drafted by Szilard. Had I known that the fear was not justified, I would not have participated in opening this Pandora's box, nor would Szilard. For my distrust of governments was not limited to Germany." Rumors or Reality? American and British nuclear physicists felt they needed to start a A-bomb project to avoid falling behind their German counterparts. They feared Hitler's forces would be the first to have use of atomic arms. This evaluation was based on a number of considerations: • The pre-war stop of uranium export • The high caliber of German theoretical and experimental physicists like Otto Hahn, Paul Harteck, Werner Heisenberg, Fritz Strassmann, and Carl-Friedrich von Weizsäcker; • German control of Europe's only uranium mine after the conquest of Czechoslovakia; • German capture of the world's largest supply of imported uranium with the fall of Belgium; • German possession of Europe's only cyclotron with the fall of France in 1940; • German control of the world's only commercial source of heavy water after its occupation of Norway. -

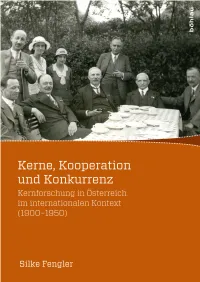

Kerne, Kooperation Und Konkurrenz. Kernforschung In

Wissenschaft, Macht und Kultur in der modernen Geschichte Herausgegeben von Mitchell G. Ash und Carola Sachse Band 3 Silke Fengler Kerne, Kooperation und Konkurrenz Kernforschung in Österreich im internationalen Kontext (1900–1950) 2014 Böhlau Verlag Wien Köln Weimar The research was funded by the Austrian Science Fund (FWF) : P 19557-G08 Bibliografische Information der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek: Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek verzeichnet diese Publikation in der Deutschen Nationalbibliografie; detaillierte bibliografische Datensind im Internet über http://dnb.d-nb.de abrufbar. Umschlagabbildung: Zusammentreffen in Hohenholte bei Münster am 18. Mai 1932 anlässlich der 37. Hauptversammlung der deutschen Bunsengesellschaft für angewandte physikalische Chemie in Münster (16. bis 19. Mai 1932). Von links nach rechts: James Chadwick, Georg von Hevesy, Hans Geiger, Lili Geiger, Lise Meitner, Ernest Rutherford, Otto Hahn, Stefan Meyer, Karl Przibram. © Österreichische Zentralbibliothek für Physik, Wien © 2014 by Böhlau Verlag Ges.m.b.H & Co. KG, Wien Köln Weimar Wiesingerstraße 1, A-1010 Wien, www.boehlau-verlag.com Alle Rechte vorbehalten. Dieses Werk ist urheberrechtlich geschützt. Jede Verwertung außerhalb der engen Grenzen des Urheberrechtsgesetzes ist unzulässig. Lektorat: Ina Heumann Korrektorat: Michael Supanz Umschlaggestaltung: Michael Haderer, Wien Satz: Michael Rauscher, Wien Druck und Bindung: Prime Rate kft., Budapest Gedruckt auf chlor- und säurefrei gebleichtem Papier Printed in Hungary ISBN 978-3-205-79512-4 Inhalt 1. Kernforschung in Österreich im Spannungsfeld von internationaler Kooperation und Konkurrenz ....................... 9 1.1 Internationalisierungsprozesse in der Radioaktivitäts- und Kernforschung : Eine Skizze ...................... 9 1.2 Begriffsklärung und Fragestellungen ................. 10 1.2.2 Ressourcenausstattung und Ressourcenverteilung ......... 12 1.2.3 Zentrum und Peripherie ..................... 14 1.3 Forschungsstand ........................... 16 1.4 Quellenlage ............................. -

Max Planck Institute for the History of Science Werner Heisenberg And

MAX-PLANCK-INSTITUT FÜR WISSENSCHAFTSGESCHICHTE Max Planck Institute for the History of Science PREPRINT 203 (2002) Horst Kant Werner Heisenberg and the German Uranium Project Otto Hahn and the Declarations of Mainau and Göttingen Werner Heisenberg and the German Uranium Project* Horst Kant Werner Heisenberg’s (1901-1976) involvement in the German Uranium Project is the most con- troversial aspect of his life. The controversial discussions on it go from whether Germany at all wanted to built an atomic weapon or only an energy supplying machine (the last only for civil purposes or also for military use for instance in submarines), whether the scientists wanted to support or to thwart such efforts, whether Heisenberg and the others did really understand the mechanisms of an atomic bomb or not, and so on. Examples for both extreme positions in this controversy represent the books by Thomas Powers Heisenberg’s War. The Secret History of the German Bomb,1 who builds up him to a resistance fighter, and by Paul L. Rose Heisenberg and the Nazi Atomic Bomb Project – A Study in German Culture,2 who characterizes him as a liar, fool and with respect to the bomb as a poor scientist; both books were published in the 1990s. In the first part of my paper I will sum up the main facts, known on the German Uranium Project, and in the second part I will discuss some aspects of the role of Heisenberg and other German scientists, involved in this project. Although there is already written a lot on the German Uranium Project – and the best overview up to now supplies Mark Walker with his book German National Socialism and the quest for nuclear power, which was published in * Paper presented on a conference in Moscow (November 13/14, 2001) at the Institute for the History of Science and Technology [àÌÒÚËÚÛÚ ËÒÚÓËË ÂÒÚÂÒÚ‚ÓÁ̇ÌËfl Ë ÚÂıÌËÍË ËÏ. -

Heisenberg and the Nazi Atomic Bomb Project, 1939-1945: a Study in German Culture

Heisenberg and the Nazi Atomic Bomb Project http://content.cdlib.org/xtf/view?docId=ft838nb56t&chunk.id=0&doc.v... Preferred Citation: Rose, Paul Lawrence. Heisenberg and the Nazi Atomic Bomb Project, 1939-1945: A Study in German Culture. Berkeley: University of California Press, c1998 1998. http://ark.cdlib.org/ark:/13030/ft838nb56t/ Heisenberg and the Nazi Atomic Bomb Project A Study in German Culture Paul Lawrence Rose UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PRESS Berkeley · Los Angeles · Oxford © 1998 The Regents of the University of California In affectionate memory of Brian Dalton (1924–1996), Scholar, gentleman, leader, friend And in honor of my father's 80th birthday Preferred Citation: Rose, Paul Lawrence. Heisenberg and the Nazi Atomic Bomb Project, 1939-1945: A Study in German Culture. Berkeley: University of California Press, c1998 1998. http://ark.cdlib.org/ark:/13030/ft838nb56t/ In affectionate memory of Brian Dalton (1924–1996), Scholar, gentleman, leader, friend And in honor of my father's 80th birthday ― ix ― ACKNOWLEDGMENTS For hospitality during various phases of work on this book I am grateful to Aryeh Dvoretzky, Director of the Institute of Advanced Studies of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, whose invitation there allowed me to begin work on the book while on sabbatical leave from James Cook University of North Queensland, Australia, in 1983; and to those colleagues whose good offices made it possible for me to resume research on the subject while a visiting professor at York University and the University of Toronto, Canada, in 1990–92. Grants from the College of the Liberal Arts and the Institute for the Arts and Humanistic Studies of The Pennsylvania State University enabled me to complete the research and writing of the book. -

ABSTRACT Title of Dissertation: the PRINCIPAL UNCERTAINTY: U.S

ABSTRACT Title of Dissertation: THE PRINCIPAL UNCERTAINTY: U.S. ATOMIC INTELLIGENCE, 1942-1949 Vincent Jonathan Houghton, Doctor of Philosophy, 2013 Dissertation directed by: Professor Jon T. Sumida Department of History The subject of this dissertation is the U. S. atomic intelligence effort against both Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union in the period 1942-1949. Both of these intelligence efforts operated within the framework of an entirely new field of intelligence: scientific intelligence. Because of the atomic bomb, for the first time in history a nation’s scientific resources – the abilities of its scientists, the state of its research institutions and laboratories, its scientific educational system – became a key consideration in assessing a potential national security threat. Considering how successfully the United States conducted the atomic intelligence effort against the Germans in the Second World War, why was the United States Government unable to create an effective atomic intelligence apparatus to monitor Soviet scientific and nuclear capabilities? Put another way, why did the effort against the Soviet Union fail so badly, so completely, in all potential metrics – collection, analysis, and dissemination? In addition, did the general assessment of German and Soviet science lead to particular assumptions about their abilities to produce nuclear weapons? How did this assessment affect American presuppositions regarding the German and Soviet strategic threats? Despite extensive historical work on atomic intelligence, the current historiography has not adequately addressed these questions. THE PRINCIPAL UNCERTAINTY: U.S. ATOMIC INTELLIGENCE, 1942-1949 By Vincent Jonathan Houghton Dissertation submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Maryland, College Park, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2013 Advisory Committee: Professor Jon T. -

Hitler's Uranium Club, the Secret Recordings at Farm Hall

HITLER’S URANIUM CLUB DER FARMHALLER NOBELPREIS-SONG (Melodie: Studio of seiner Reis) Detained since more than half a year Ein jeder weiss, das Unglueck kam Sind Hahn und wir in Farm Hall hier. Infolge splitting von Uran, Und fragt man wer is Schuld daran Und fragt man, wer ist Schuld daran, So ist die Antwort: Otto Hahn. So ist die Antwort: Otto Hahn. The real reason nebenbei Die energy macht alles waermer. Ist weil we worked on nuclei. Only die Schweden werden aermer. Und fragt man, wer ist Schuld daran, Und fragt man, wer ist Schuld daran, So ist die Antwort: Otto Hahn. So ist die Antwort: Otto Hahn. Die nuclei waren fuer den Krieg Auf akademisches Geheiss Und fuer den allgemeinen Sieg. Kriegt Deutschland einen Nobel-Preis. Und fragt man, wer ist Schuld daran, Und fragt man, wer ist Schuld daran, So ist die Antwort: Otto Hahn. So ist die Antwort: Otto Hahn. Wie ist das moeglich, fragt man sich, In Oxford Street, da lebt ein Wesen, The story seems wunderlich. Die wird das heut’ mit Thraenen lesen. Und fragt man, wer ist Schuld daran Und fragt man, wer ist Schuld daran, So ist die Antwort: Otto Hahn. So ist die Antwort: Otto Hahn. Die Feldherrn, Staatschefs, Zeitungsknaben, Es fehlte damals nur ein atom, Ihn everyday im Munde haben. Haett er gesagt: I marry you madam. Und fragt man, wer ist Schuld daran, Und fragt man, wer ist Schuld daran, So ist die Antwort: Otto Hahn. So ist die Antwort: Otto Hahn. Even the sweethearts in the world(s) Dies ist nur unsre-erste Feier, Sie nennen sich jetzt: “Atom-girls.” Ich glaub die Sache wird noch teuer, Und fragt man, wer ist Schuld daran, Und fragt man, wer ist Schuld daran, So ist die Antwort: Otto Hahn. -

Farm Hall Transcripts)

Volume 7. Nazi Germany, 1933-1945 Transcript of Surreptitiously Taped Conversations among German Nuclear Physicists at Farm Hall (August 6-7, 1945) At the beginning of the war, Germany’s leading nuclear physicists were called to the army weapons department. There, as part of the “uranium project” under the direction of Werner Heisenberg, they were charged with determining the extent to which nuclear fission could aid in the war effort. (Nuclear fission had been discovered by Otto Hahn and Lise Meitner in 1938.) Unlike their American colleagues in the Manhattan Project, German physicists did not succeed in building their own nuclear weapon. In June 1942, the researchers informed Albert Speer that they were in no position to build an atomic bomb with the resources at hand in less than 3-5 years, at which point the project was scrapped. After the end of the war, both the Western Allies and the Soviet Union tried to recruit the German scientists for their own purposes. From July 3, 1945, to January 3, 1946, the Allies incarcerated ten German nuclear physicists at the English country estate of Farm Hall, their goal being to obtain information about the German nuclear research project by way of surreptitiously taped conversations. The following transcript includes the scientists’ reactions to reports that America had dropped an atomic bomb on Hiroshima. The scientists also discuss their relationship to the Nazi regime and offer some prognoses for Germany’s future. As the transcript shows, Otto Hahn was especially shaken by the dropping of the bomb; later, he campaigned against the misuse of nuclear energy for military purposes.