Global Genetic Patterns Reveal Host Tropism Versus Cross-Taxon Transmission of Bat

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Predicted the Impacts of Climate Change and Extreme-Weather Events on the Future

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.05.13.443960; this version posted May 14, 2021. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license. Predicted the impacts of climate change and extreme-weather events on the future distribution of fruit bats in Australia Vishesh L. Diengdoh1, e: [email protected], ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000- 0002-0797-9261 Stefania Ondei1 - e: [email protected] Mark Hunt1, 3 - e: [email protected] Barry W. Brook1, 2 - e: [email protected] 1School of Natural Sciences, University of Tasmania, Private Bag 55, Hobart TAS 7005 Australia 2ARC Centre of Excellence for Australian Biodiversity and Heritage, Australia 3National Centre for Future Forest Industries, Australia Corresponding Author: Vishesh L. Diengdoh Acknowledgements We thank John Clarke and Vanessa Round from Climate Change in Australia (https://www.climatechangeinaustralia.gov.au/)/ Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO) for providing the data on extreme weather events. This work was supported by the Australian Research Council [grant number FL160100101]. Conflict of Interest None. Author Contributions bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.05.13.443960; this version posted May 14, 2021. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license. -

A Novel Rhabdovirus Infecting Newly Discovered Nycteribiid Bat Flies

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN Kanyawara Virus: A Novel Rhabdovirus Infecting Newly Discovered Nycteribiid Bat Flies Received: 19 April 2017 Accepted: 25 May 2017 Infesting Previously Unknown Published: xx xx xxxx Pteropodid Bats in Uganda Tony L. Goldberg 1,2,3, Andrew J. Bennett1, Robert Kityo3, Jens H. Kuhn4 & Colin A. Chapman3,5 Bats are natural reservoir hosts of highly virulent pathogens such as Marburg virus, Nipah virus, and SARS coronavirus. However, little is known about the role of bat ectoparasites in transmitting and maintaining such viruses. The intricate relationship between bats and their ectoparasites suggests that ectoparasites might serve as viral vectors, but evidence to date is scant. Bat flies, in particular, are highly specialized obligate hematophagous ectoparasites that incidentally bite humans. Using next- generation sequencing, we discovered a novel ledantevirus (mononegaviral family Rhabdoviridae, genus Ledantevirus) in nycteribiid bat flies infesting pteropodid bats in western Uganda. Mitochondrial DNA analyses revealed that both the bat flies and their bat hosts belong to putative new species. The coding-complete genome of the new virus, named Kanyawara virus (KYAV), is only distantly related to that of its closest known relative, Mount Elgon bat virus, and was found at high titers in bat flies but not in blood or on mucosal surfaces of host bats. Viral genome analysis indicates unusually low CpG dinucleotide depletion in KYAV compared to other ledanteviruses and rhabdovirus groups, with KYAV displaying values similar to rhabdoviruses of arthropods. Our findings highlight the possibility of a yet- to-be-discovered diversity of potentially pathogenic viruses in bat ectoparasites. Bats (order Chiroptera) represent the second largest order of mammals after rodents (order Rodentia). -

Floral Biology and Pollination Strategy of Durio (Malvaceae) in Sarawak, Malaysian Borneo

BIODIVERSITAS ISSN: 1412-033X Volume 21, Number 12, December 2020 E-ISSN: 2085-4722 Pages: 5579-5594 DOI: 10.13057/biodiv/d211203 Floral biology and pollination strategy of Durio (Malvaceae) in Sarawak, Malaysian Borneo NG WIN SENG1, JAYASILAN MOHD-AZLAN1, WONG SIN YENG1,2,♥ 1Institute of Biodiversity and Environmental Conservation, Universiti Malaysia Sarawak. 94300 Kota Samarahan, Sarawak, Malaysia. 2Harvard University Herbaria. 22 Divinity Avenue, Cambridge, MA 02138, United States of America. ♥ email: [email protected]. Manuscript received: 25 September 2020. Revision accepted: 4 November 2020. Abstract. Ng WS, Mohd-Azlan J, Wong SY. 2020. Floral biology and pollination strategy of Durio (Malvaceae) in Sarawak, Malaysian Borneo. Biodiversitas 21: 5579-5594. This study was carried out to investigate on the flowering mechanisms of four Durio species in Sarawak. The anthesis started in the afternoon (D. graveolens and D. zibethinus), evening (D. kutejensis) or midnight (D. griffithii); and lasted between 11.5 hours (D. griffithii) to 20 hours (D. graveolens). All four Durio species are generalists. Individuals of a fruit bat (Eonycteris spelaea, Pteropodidae) are considered as the main pollinator for D. graveolens, D. kutejensis, and D. zibethinus while spiderhunter (Arachnothera, Nectariniidae) is also proposed as a primary pollinator for D. kutejensis. Five invertebrate taxa were observed as secondary or inadvertent pollinators of Durio spp.: honeybee, Apis sp. (Apidae), stingless bee, Tetrigona sp. (Apidae), nocturnal wasp, Provespa sp. (Vespidae), pollen beetle (Nitidulidae), and thrip (Thysanoptera). Honey bees and stingless bees pollinated all four Durio species. Pollen beetles were found to pollinate D. griffithii and D. graveolens while nocturnal wasps were found to pollinate D. -

Seasonal Shedding of Coronaviruses in Straw-Colored Fruit Bats at Urban Roosts in Africa

Seasonal Shedding of Coronaviruses in Straw-colored Fruit Bats at Urban Roosts in Africa The adaptation of bats (order Chiroptera) to use and For these reasons, we assessed the seasonality of occupy human dwellings across the planet has created coronavirus (CoV) shedding by the straw-colored intensive bat-human interfaces. Because bats provide fruit bat (Eidolon helvum) by passively collecting 97 important ecosystem services and also host and shed fecal samples on a monthly basis during a entire year zoonotic viruses, these interfaces represent a double in two urban colonies: Accra, Ghana (West Africa) challenge: i) the conservation of bats and their services and Morogoro, Tanzania (East Africa; Fig 1). Sampling and ii) the prevention of viral spillover. collection was conducted under the same trees during Many species of bats have evolved a seasonal life the study period. This species of fruit bat shows a single history that has resulted in the development of specific birth pulse during the year, its colonies show spectacular reproductive and foraging activities during distinctive periodical changes in size, and similarly to other tree- periods of the year. For example, many species mate, roosting megabats, several roosts are located in busy give birth, and nurse during particular and predictable urban centers across sub-Saharan Africa. Moreover, times of the year. Moreover, bat migration can produce we concomitantly collected data on the roost sizes predictable variations in colony sizes during a typical and precipitation levels over time, and we established year, from a complete absence of bats to the aggregation the reproductive periods through the year (birth of millions of individuals depending on the season. -

A Recent Bat Survey Reveals Bukit Barisan Selatan Landscape As A

A Recent Bat Survey Reveals Bukit Barisan Selatan Landscape as a Chiropteran Diversity Hotspot in Sumatra Author(s): Joe Chun-Chia Huang, Elly Lestari Jazdzyk, Meyner Nusalawo, Ibnu Maryanto, Maharadatunkamsi, Sigit Wiantoro, and Tigga Kingston Source: Acta Chiropterologica, 16(2):413-449. Published By: Museum and Institute of Zoology, Polish Academy of Sciences DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.3161/150811014X687369 URL: http://www.bioone.org/doi/full/10.3161/150811014X687369 BioOne (www.bioone.org) is a nonprofit, online aggregation of core research in the biological, ecological, and environmental sciences. BioOne provides a sustainable online platform for over 170 journals and books published by nonprofit societies, associations, museums, institutions, and presses. Your use of this PDF, the BioOne Web site, and all posted and associated content indicates your acceptance of BioOne’s Terms of Use, available at www.bioone.org/page/terms_of_use. Usage of BioOne content is strictly limited to personal, educational, and non-commercial use. Commercial inquiries or rights and permissions requests should be directed to the individual publisher as copyright holder. BioOne sees sustainable scholarly publishing as an inherently collaborative enterprise connecting authors, nonprofit publishers, academic institutions, research libraries, and research funders in the common goal of maximizing access to critical research. Acta Chiropterologica, 16(2): 413–449, 2014 PL ISSN 1508-1109 © Museum and Institute of Zoology PAS doi: 10.3161/150811014X687369 A recent -

Zoologische Mededelingen

ZOOLOGISCHE MEDEDELINGEN UITGEGEVEN DOOR HET RIJKSMUSEUM VAN NATUURLIJKE HISTORIE TE LEIDEN (MINISTERIE VAN CULTUUR, RECREATIE EN MAATSCHAPPELIJK WERK) Deel 55 no. 14 4 maart 1980 A NEW FRUIT BAT OF THE GENUS MYONYCTERIS MATSCHIE, 1899, FROM EASTERN KENYA AND TANZANIA (MAMMALIA, MEGACHIROPTERA) by W. BERGMANS Instituut voor Taxonomische Zoölogie, Universiteit van Amsterdam With 4 text-figures ABSTRACT Myonycteris relicta n. sp. is described from the Shimba Hills in southeast Kenya and from the Usambara Mountains in northeast Tanzania. The species is larger than the only other known African mainland species of the genus, Myonycteris torquata (Dobson, 1878), from the Central and West African rain forests and, if compared to M. torquata and the only other species in the genus, M. brachycephala (Bocage, 1889) from São Tomé, has a relatively longer rostrum, a more deflected cranial axis, and further differs in number, shape and position of its teeth. The new species provides new arguments for the relationship between the genera Myonycteris Matschie, 1899, and Lissonycteris Andersen, 1912. It is believed that Myonycteris relicta may be a forest species and as such restricted to isolated East African forests. INTRODUCTION During a visit to the Zoologisches Museum in Berlin (ZMB), in April 1979, the author found two fruit bat specimens from the Tanzanian Usa- mbara Mountains, which proved to represent an undescribed taxon. Later, in June 1979, Dr C. Smeenk of the Rijksmuseum van Natuurlijke Historie at Leiden (RMNH) recognized a third specimen of this taxon in newly acquired material from the Shimba Hills in southeast Kenya. The bats differ on specific level from all other known fruit bats, and are described in the present paper. -

Chiroptera: Pteropodidae)

Chapter 6 Phylogenetic Relationships of Harpyionycterine Megabats (Chiroptera: Pteropodidae) NORBERTO P. GIANNINI1,2, FRANCISCA CUNHA ALMEIDA1,3, AND NANCY B. SIMMONS1 ABSTRACT After almost 70 years of stability following publication of Andersen’s (1912) monograph on the group, the systematics of megachiropteran bats (Chiroptera: Pteropodidae) was thrown into flux with the advent of molecular phylogenetics in the 1980s—a state where it has remained ever since. One particularly problematic group has been the Austromalayan Harpyionycterinae, currently thought to include Dobsonia and Harpyionycteris, and probably also Aproteles.Inthis contribution we revisit the systematics of harpyionycterines. We examine historical hypotheses of relationships including the suggestion by O. Thomas (1896) that the rousettine Boneia bidens may be related to Harpyionycteris, and report the results of a series of phylogenetic analyses based on new as well as previously published sequence data from the genes RAG1, RAG2, vWF, c-mos, cytb, 12S, tVal, 16S,andND2. Despite a striking lack of morphological synapomorphies, results of our combined analyses indicate that Boneia groups with Aproteles, Dobsonia, and Harpyionycteris in a well-supported, expanded Harpyionycterinae. While monophyly of this group is well supported, topological changes within this clade across analyses of different data partitions indicate conflicting phylogenetic signals in the mitochondrial partition. The position of the harpyionycterine clade within the megachiropteran tree remains somewhat uncertain. Nevertheless, biogeographic patterns (vicariance-dispersal events) within Harpyionycterinae appear clear and can be directly linked to major biogeographic boundaries of the Austromalayan region. The new phylogeny of Harpionycterinae also provides a new framework for interpreting aspects of dental evolution in pteropodids (e.g., reduction in the incisor dentition) and allows prediction of roosting habits for Harpyionycteris, whose habits are unknown. -

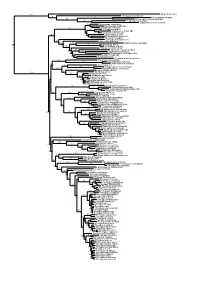

Figs1 ML Tree.Pdf

100 Megaderma lyra Rhinopoma hardwickei 71 100 Rhinolophus creaghi 100 Rhinolophus ferrumequinum 100 Hipposideros armiger Hipposideros commersoni 99 Megaerops ecaudatus 85 Megaerops niphanae 100 Megaerops kusnotoi 100 Cynopterus sphinx 98 Cynopterus horsfieldii 69 Cynopterus brachyotis 94 50 Ptenochirus minor 86 Ptenochirus wetmorei Ptenochirus jagori Dyacopterus spadiceus 99 Sphaerias blanfordi 99 97 Balionycteris maculata 100 Aethalops alecto 99 Aethalops aequalis Thoopterus nigrescens 97 Alionycteris paucidentata 33 99 Haplonycteris fischeri 29 Otopteropus cartilagonodus Latidens salimalii 43 88 Penthetor lucasi Chironax melanocephalus 90 Syconycteris australis 100 Macroglossus minimus 34 Macroglossus sobrinus 92 Boneia bidens 100 Harpyionycteris whiteheadi 69 Harpyionycteris celebensis Aproteles bulmerae 51 Dobsonia minor 100 100 80 Dobsonia inermis Dobsonia praedatrix 99 96 14 Dobsonia viridis Dobsonia peronii 47 Dobsonia pannietensis 56 Dobsonia moluccensis 29 Dobsonia anderseni 100 Scotonycteris zenkeri 100 Casinycteris ophiodon 87 Casinycteris campomaanensis Casinycteris argynnis 99 100 Eonycteris spelaea 100 Eonycteris major Eonycteris robusta 100 100 Rousettus amplexicaudatus 94 Rousettus spinalatus 99 Rousettus leschenaultii 100 Rousettus aegyptiacus 77 Rousettus madagascariensis 87 Rousettus obliviosus Stenonycteris lanosus 100 Megaloglossus woermanni 100 91 Megaloglossus azagnyi 22 Myonycteris angolensis 100 87 Myonycteris torquata 61 Myonycteris brachycephala 33 41 Myonycteris leptodon Myonycteris relicta 68 Plerotes anchietae -

Bat Count 2003

BAT COUNT 2003 Working to promote the long term, sustainable conservation of globally threatened flying foxes in the Philippines, by developing baseline population information, increasing public awareness, and training students and protected area managers in field monitoring techniques. 1 A Terminal Report Submitted by Tammy Mildenstein1, Apolinario B. Cariño2, and Samuel Stier1 1Fish and Wildlife Biology, University of Montana, USA 2Silliman University and Mt. Talinis – Twin Lakes Federation of People’s Organizations, Diputado Extension, Sibulan, Negros Oriental, Philippines Photo by: Juan Pablo Moreiras 2 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Large flying foxes in insular Southeast Asia are the most threatened of the Old World fruit bats due to deforestation, unregulated hunting, and little conservation commitment from local governments. Despite the fact they are globally endangered and play essential ecological roles in forest regeneration as seed dispersers and pollinators, there have been only a few studies on these bats that provide information useful to their conservation management. Our project aims to promote the conservation of large flying foxes in the Philippines by providing protected area managers with the training and the baseline information necessary to design and implement a long-term management plan for flying foxes. We focused our efforts on the globally endangered Philippine endemics, Acerodon jubatus and Acerodon leucotis, and the bats that commonly roost with them, Pteropus hypomelanus, P. vampyrus lanensis, and P. pumilus which are thought to be declining in the Philippines. Local participation is an integral part of our project. We conducted the first national training workshop on flying fox population counts and conservation at the Subic Bay area. -

Diversity and Evolution of Viral Pathogen Community in Cave Nectar Bats (Eonycteris Spelaea)

viruses Article Diversity and Evolution of Viral Pathogen Community in Cave Nectar Bats (Eonycteris spelaea) Ian H Mendenhall 1,* , Dolyce Low Hong Wen 1,2, Jayanthi Jayakumar 1, Vithiagaran Gunalan 3, Linfa Wang 1 , Sebastian Mauer-Stroh 3,4 , Yvonne C.F. Su 1 and Gavin J.D. Smith 1,5,6 1 Programme in Emerging Infectious Diseases, Duke-NUS Medical School, Singapore 169857, Singapore; [email protected] (D.L.H.W.); [email protected] (J.J.); [email protected] (L.W.); [email protected] (Y.C.F.S.) [email protected] (G.J.D.S.) 2 NUS Graduate School for Integrative Sciences and Engineering, National University of Singapore, Singapore 119077, Singapore 3 Bioinformatics Institute, Agency for Science, Technology and Research, Singapore 138671, Singapore; [email protected] (V.G.); [email protected] (S.M.-S.) 4 Department of Biological Sciences, National University of Singapore, Singapore 117558, Singapore 5 SingHealth Duke-NUS Global Health Institute, SingHealth Duke-NUS Academic Medical Centre, Singapore 168753, Singapore 6 Duke Global Health Institute, Duke University, Durham, NC 27710, USA * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 30 January 2019; Accepted: 7 March 2019; Published: 12 March 2019 Abstract: Bats are unique mammals, exhibit distinctive life history traits and have unique immunological approaches to suppression of viral diseases upon infection. High-throughput next-generation sequencing has been used in characterizing the virome of different bat species. The cave nectar bat, Eonycteris spelaea, has a broad geographical range across Southeast Asia, India and southern China, however, little is known about their involvement in virus transmission. -

Anatomy and Histology of the Heart in Egyptian Fruit

Journal of Entomology and Zoology Studies 2016; 4(5): 50-56 E-ISSN: 2320-7078 P-ISSN: 2349-6800 JEZS 2016; 4(5): 50-56 Anatomy and histology of the heart in Egyptian © 2016 JEZS fruit bat (Rossetus aegyptiacus) Received: 09-09-2016 Accepted: 10-10-2016 Bahareh Alijani Bahareh Alijani and Farangis Ghassemi Department of Biology, Jahrom branch, Islamic Azad University, Abstract Jahrom, Iran This study was conducted to obtain more information about bats to help their conservation. Since 5 fruit Farangis Ghassemi bats, Rossetus aegyptiacus, weighing 123.04±0.08 g were captured using mist net. They were Department of Biology, Jahrom anesthetized and dissected in animal lab. The removed heart components were measured, fixed, and branch, Islamic Azad University, tissue processing was done. The prepared sections (5 µm) were subjected to Haematoxylin and Eosin Jahrom, Iran stain, and mounted by light microscope. Macroscopic and microscopic features of specimens were examined, and obtained data analyzed by ANOVA test. The results showed that heart was oval and closed in the transparent pericardium. The left and right side of heart were different significantly in volume and wall thickness of chambers. Heart was large and the heart ratio was 1.74%. Abundant fat cells, intercalated discs, and purkinje cells were observed. According to these results, heart in this species is similar to the other mammals and observed variation, duo to the high metabolism and energy requirements for flight. Keywords: Heart, muscle, bat, flight, histology 1. Introduction Bats are the only mammals that are able to fly [1]. Due to this feature, the variation in the [2, 3] morphology and physiology of their organs such as cardiovascular organs is expected Egyptian fruit bat (Rossetus aegyptiacus) belongs to order megachiroptera and it is the only megabat in Iran [4]. -

Final Report on the Project

BP Conservation Programme (CLP) 2005 PROJECT NO. 101405 - BRONZE AWARD WINNER ECOLOGY, DISTRIBUTION, STATUS AND PROTECTION OF THREE CONGOLESE FRUIT BATS FINAL REPORT Patrick KIPALU Team Leader Observatoire Congolais pour la Protection de l’Environnement OCPE – ong Kinshasa – Democratic Republic of the Congo E-mail: [email protected] APRIL 2009 1 Table of Content Acknowledgements…………………………………………………………………. p3 I. Project Summary……………………………………………………………….. p4 II. Introduction…………………………………………………………………… p4-p7 III. Materials and Methods ……………………………………………………….. p7-p10 IV. Results per Study Site…………………………………………………………. p10-p15 1. Pointe-Noire ………………………………………………………….. p10-p12 2. Mayumbe Forest /Luki Reserve……………………………………….. p12-p13 3. Zongo Forest…………………………………………………………... p14 4. Mbanza-Ngungu ………………………………………………………. P15 V. General Results ………………………………………………………………p15-p16 VI. Discussions……………………………………………………………………p17-18 VII. Conclusion and Recommendations……………………………………….p 18-p19 VIII. Bibliography………………………………………………………………p20-p21 Acknowledgements 2 The OCPE (Observatoire Congolais pour la Protection de l’Environnement) project team would like to start by expressing our gratefulness and saying thank you to the BP Conservation Program, which has funded the execution of this project. The OCPE also thanks the Van Tienhoven Foundation which provided a further financial support. Without these organisations, execution of the project would not have been possible. We would like to thank specially the BPCP “dream team”: Marianne D. Carter, Robyn Dalzen and our regretted Kate Stoke for their time, advices, expertise and care, which helped us to complete this work, Our special gratitude goes to Dr. Wim Bergmans, who was the hero behind the scene from the conception to the execution of the research work. Without his expertise, advices and network it would had been difficult for the project team to produce any result from this project.