5. Anomalies in the Data

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

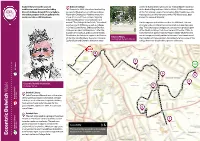

Eccentric Dulwich Walk Eccentric and Exit Via the Old College Gate

Explore Dulwich and its unusual 3 Dulwich College writer; Sir Edward George (known as “Steady Eddie”, Governor architecture and characters including Founded in 1619, the school was built by of the Bank of England from 1993 to 2003); C S Forester, writer Dulwich College, Dulwich Picture Gallery - successful Elizabethan actor Edward Alleyn. of the Hornblower novels; the comedian, Bob Monkhouse, who the oldest purpose-built art gallery in the Playwright Christopher Marlowe wrote him was expelled, and the humorous writer PG Wodehouse, best world, and Herne Hill Velodrome. some of his most famous roles. Originally known for Jeeves & Wooster. meant to educate 12 “poor scholars” and named “The College of God’s Gift,” the school On the opposite side of the road lies The Mill Pond. This was now has over 1,500 boys, as well as colleges originally a clay pit where the raw materials to make tiles were in China & South Korea. Old boys of Dulwich dug. The picturesque cottages you can see were probably part College are called “Old Alleynians”, after the of the tile kiln buildings that stood here until the late 1700s. In founder of the school, and include: Sir Ernest 1870 the French painter Camille Pissarro (1830-1903) fled the Shackleton, the Antarctic explorer; Ed Simons war in Europe and briefly settled in the area. Considered one of Edward Alleyn, of the Chemical Brothers; the actor, Chiwetel the founders of Impressionism, he painted a famous view of the photograph by Sara Moiola Ejiofor; Raymond Chandler, detective story college from here (now held in a private collection). -

The Edward Alleyn Golf Society, It Was for Me Immensely Enjoyable in My Own 49Th Year

T he Edward Alleyn G olf Society (Established 1968) Hon. Secretary: President: Dr Gary Savage MA PhD George Thorne Past Presidents: Sir Henry Cotton KCMG MBE 4 Bell Meadow Derek Fenner MA London Dr Colin Niven OBE SE19 1HP Dr Colin Diggory MA EdD [email protected] Tel: 0208 488 7828 The Society Christmas Dinner and Annual General Meeting will be held on Friday 8th December 2017 at Dulwich & Sydenham Hill GC, commencing with a drinks reception at 19:00. Present: Vince Abel, Steve Bargeron, Peter Battle, James Bridgeman, Tracy Bridgeman, Dave Britton, Roger Brunner, Andre Cutress, Roger Dollimore, Neil Hardwick, Perry Harley, Bob Joyce, John Knight, Dennis Lomas, Alan Miles, Roger Parkinson, Ted Pearce, Steve Poole, Jack Roberts, Keith Rodwell, John Smith, Ray Stiles, Justin Sutton, George Thorne, Tim Wareham, Alan Williams, Anton Williams; Guests: John Battle, Roy Croft, Neil French, Chris Nelson. Apologies: Mikael Berglund, Chris Briere-Edney, Trevor Cain, Dave Cleveland, Dom Cleveland, Len Cleveland, John Coleman, John Dunley, Dr Colin Diggory MA,EdD, John Etches, Ray Eyre, David Foulds, Mike Froggatt, Mark Gardner, David Hankin, Peter Holland, Bruce Leary, Dave McEvoy, Dave Sandars, Andrew Saunders, Paul Selwyn, Dave Slaney, Chris Shirtcliffe, Dr Gary Savage MA,PhD. In Memoriam A minute’s silence in memory of Society Members and other Alumni who have passed away this year : Kit Miller, attended 10 meetings between 1976 and 1991; Jim Calvo, attended 11 meetings and many tours between 2001 and 2015; Steve Crosby, attended 2 meetings in 1993-4; Brian Romilly non-golfer, but a great friend of many of our members. -

Newsletter #104 (Spring 1995)

The Dulwich Society - Newsletter 104 Spring - 1995 Contents What's on 1 Dulwich Park 13 Annual General Meeting 3 Wildlife 14 Obituary: Ronnie Reed 4 The Watchman Tree 16 Conservation Trust 7 Edward Alleyn Mystery 20 Transport 8 Letters 35 Chairman Joint Membership Secretaries Reg Collins Robin and Wilfrid Taylor 6 Eastlands Crescent, SE21 7EG 30 Walkerscroft Mead, SE21 81J Tel: 0181-693 1223 Tel: 0181-670 0890 Vice Chairman Editor W.P. Higman Brian McConnell 170 Burbage Road, SE21 7AG 9 Frank Dixon W1y, SE2 I 7ET Tel: 0171-274 6921 Tel & Fax: 0181-693 4423 Secretary Patrick Spencer Features Editor 7 Pond Cottages, Jane Furnival College Road, SE21 7LE 28 Little Bornes, SE21 SSE Tel: 0181-693 2043 Tel: 0181-670 6819 Treasurer Advertising Manager Russell Lloyd Anne-Maree Sheehan 138 Woodwarde Road, SE22 SUR 58 Cooper Close, SE! 7QU Tel: 0181-693 2452 Tel: 0171-928 4075 Registered under the Charities Act 1960 Reg. No. 234192 Registered with the Civic Trust Typesetting and Printing: Postal Publicity Press (S.J. Heady & Co. Ltd.) 0171-622 2411 1 DULWICH SOCIETY EVENTS NOTICE is hereby given that the 32nd Annual General Meeting of The 1995 Dulwich Society will be held at 8 p.m. on Friday March 10 1995 at St Faith's Friday, March 10. Annual General Meeting, St Faith's Centre, Red Post Hill, Community and Youth Centre, Red Post Hill, SE24 9JQ. 8p.m. Friday, March 24. Illustrated lecture, "Shrubs and herbaceous perennials for AGENDA the spring" by Aubrey Barker of Hopley's Nurseries. St Faith's Centre. -

"A Sharers' Repertory." Rethinking Theatrical

Syme, Holger Schott. "A Sharers’ Repertory." Rethinking Theatrical Documents in Shakespeare’s England. Ed. Tiffany Stern. London: The Arden Shakespeare, 2020. 33–51. Bloomsbury Collections. Web. 26 Sep. 2021. <http://dx.doi.org/10.5040/9781350051379.ch-002>. Downloaded from Bloomsbury Collections, www.bloomsburycollections.com, 26 September 2021, 08:28 UTC. Copyright © Tiffany Stern and contributors 2020. You may share this work for non-commercial purposes only, provided you give attribution to the copyright holder and the publisher, and provide a link to the Creative Commons licence. 2 A Sharers’ Repertory Holger Schott Syme Without Philip Henslowe, we would know next to nothing about the kinds of repertories early modern London’s resident theatre companies offered to their audiences. As things stand, thanks to the existence of the manuscript commonly known as Henslowe’s Diary , scholars have been able to contemplate the long lists of receipts and expenses that record the titles of well over 200 plays, most of them now lost. The Diary gives us some sense of the richness and diversity of this repertory, of the rapid turnover of plays, and of the kinds of investments theatre companies made to mount new shows. It also names a plethora of actors and other professionals associated with the troupes at the Rose. But, because the records are a fi nancier’s and theatre owner’s, not those of a sharer in an acting company, they do not document how a group of actors decided which plays to stage, how they chose to alternate successful shows, or what they, as actors, were looking for in new commissions. -

The Elizabethan Age

The Elizabethan Age This royal throne of kings, this sceptred isle, This earth of majesty, this seat of Mars, This other Eden, demi-paradise, This fortress built by Nature for herself Against infection and the hand of war, This happy breed of men, this little world, This precious stone set in the silver sea, Which serves it in the office of a wall Or as a moat defensive to a house, Against the envy of less happier lands,- This blessed plot, this earth, this realm, this England. – Richard II, William Shakespeare DRAMA TEACHER ACADEMY © 2015 LINDSAY PRICE 1 INDEX THE ELIZABETHAN AGE What was going on during this time period? THE ELIZABETHAN THEATRE The theatres, the companies, the audiences. STAGING THE ELIZABETHAN PLAY How does it differ from modern staging? DRAMA TEACHER ACADEMY © 2015 LINDSAY PRICE 2 Facts About Elizabethan England • The population rose from 3 to 4 million. • This increase lead to widespread poverty. • Average life expectancy was 40 years of age. • Country largely rural, though there is growth in towns and cities. • The principal industry still largely agricultural with wool as its main export. But industries such as weaving started to take hold. • Society strongly divided along class lines. • People had to dress according to their class. • The colour purple was reserved for royalty. • The religion was Protestant-Anglican – the Church of England. • There was a fine if you didn’t attend church. • Only males went to school. • The school day could run from 6 am to 5 pm. • The middle class ate a diet of grains and vegetables – meat was a luxury saved for the rich, who surprisingly ate few vegetables. -

Pembroke's Men in 1592–3, Their Repertory and Touring Schedule

Issues in Review 129 22 Leland H. Carlson, Martin Marprelate, Gentleman: Master Job Throckmorton Laid Open in his Colours (San Marino: Huntington Library, 1981), 72–81; Donald J. McGinn, John Penry and the Marprelate Controversy (New Bruns- wick, NJ, 1966), 134. 23 John Laurence, A History of Capital Punishment (New York, 1963), 9; see also Naish, Death Comes to the Maiden, 9, and Frances E. Dolan, ‘“Gentlemen, I have one more thing to say”: Women on Scaffolds in England, 1563–1680’, Modern Philology 92 (1994), 166. Pembroke’s Men in 1592–3, Their Repertory and Touring Schedule Some years ago, during a seminar on theatre history at the annual meeting of the Shakespeare Association of America, someone asked plaintively, ‘What did bad companies play in the provinces?’ and Leeds Barroll quipped, ‘Bad quartos’. The belief behind the joke – that ‘bad’ quartos and failing companies went together – has seemed specifically true of the earl of Pembroke’s players in 1592–3. Pembroke’s Men played in the provinces, and plays later published that advertised their ownership have been assigned to the category of texts known as ‘bad’ quartos. Even so, the company had reasons to be considered ‘good’. They enjoyed the patronage of Henry Herbert, the earl of Pembroke, and gave two of the five performances at court during Christmas, 1592–3 (26 December, 6 January). Their players, though probably young, were talented and committed to the profession: Richard Burbage, who would become a star with the Chamberlain’s/King’s Men, was still acting within a year of his death in 1619; William Sly acted with the Chamberlain’s/King’s Men until his death in 1608; Humphrey Jeffes acted with the Admiral’s/Prince’s/Palsgrave’s Men, 1597–1615; Robert Pallant and Robert Lee, who played with Worcester’s/ Queen Anne’s Men, were still active in the 1610s. -

Was Robert Greene's “Upstart Crow” the Actor Edward Alleyn?

The Marlowe Society Was Robert Greene’s “Upstart Crow” Research Journal - Volume 06 - 2009 the actor Edward Alleyn? Online Research Journal Article Daryl Pinksen Was Robert Greene’s “Upstart Crow” the actor Edward Alleyn? "The first mention of William Shakespeare as a writer occurred in 1592 when Robert Greene singled him out as an actor-turned-playwright who had grown too big for his britches." Such is the claim made by all Shakespeare biographers. However, a closer look at the evidence reveals what appears to be an unfortunate case of mistaken identity. Near the end of Greene's Groatsworth of Wit (September 1592) 1, Robert Greene, in an address to three fellow playwrights widely agreed to be Christopher Marlowe, Thomas Nashe and George Peele, says that an actor he calls an "upstart Crow" has become so full of himself that he now believes he is the only "Shake-scene" in the country. This puffed-up actor even dares to write blank verse and imagines himself the equal of professional playwrights. In his address to Marlowe, Nashe, and Peele, Greene reminds them that actors owe their entire careers to writers. He warns his fellow playwrights that just as he has been abandoned by these actors, it could just as easily happen to them. He urges them not to trust the actors, especially the one he calls an "upstart Crow." Finally, he pleads with them to stop writing plays for the actors, whom he variously calls "Apes," "Antics," and "Puppets." Here is Greene's warning to his fellow playwrights [following immediately from Appendix B]: Base minded men all three of you, if by my misery you be not warned: for unto none of you (like me) sought those burres to cleave: those Puppets (I mean) that spake from our mouths, those Anticks garnished in our colours. -

1 Introduction by Grace Ioppolo in 1619, the Celebrated Actor Edward

Introduction by Grace Ioppolo In 1619, the celebrated actor Edward Alleyn founded Dulwich College, a boys’ school originally called ‘God’s Gift of Dulwich College’, as part of his charitable foundation, which also included a chapel and twelve almshouses.1 As part of his estate, Alleyn left thousands of pages of his personal professional papers as well as those of his father-in-law and business partner, the entrepreneur Philip Henslowe, to the College in perpetuity. Some of the papers, including the invaluable account book of theatrical expenses now known as Henslowe’s Diary, suffered minor damage over the centuries. Yet these papers recording playhouse construction, theatre company management, the relationships of actors and dramatists with their employers, and the interaction of royal and local officials in theatre performance and production remained largely intact. Although Henslowe’s Diary and other original volumes such as the play-text of The Telltale retained their original bindings, thousands of loose documents, including muniments, deeds, leases, indentures, contracts, letters, and receipts remained uncatalogued and in their original state (included folded into packets, as in the case of letters). Scholars and theatre professionals such as David Garrick, Edmond Malone, John Payne Collier and J. O. Halliwell made use of Dulwich College’s library in the 18th and 19th centuries, sometimes borrowing and then not returning bound volumes and loose manuscripts to use in their research on the theatre history of Shakespeare and his contemporaries. In the 1870s, the governors of Dulwich College accepted the offer of George F. Warner, a keeper of manuscripts at the British Museum, to conserve and catalogue this collection of the single most important archive of documents relating to 16th and 17th century performance and production. -

Soane's Favourite Subject: the Story of Dulwich Picture Gallery #210 Pages #2000 #Dulwich Picture Gallery, 2000 #Francesco Nevola, Dulwich Picture Gallery

Soane's favourite subject: the story of Dulwich Picture Gallery #210 pages #2000 #Dulwich Picture Gallery, 2000 #Francesco Nevola, Dulwich Picture Gallery Dulwich Picture Gallery is an art gallery in Dulwich, South London. The gallery, designed by Regency architect Sir John Soane using an innovative and influential method of illumination, opened to the public in 1817. It is the oldest public art gallery in England and was made an independent charitable trust in 1994. Until this time the gallery was part of Alleyn's College of God's Gift, a charitable foundation established by the actor, entrepreneur and philanthropist Edward Alleyn in the early-17th Dulwich Picture Gallery is an art gallery in Dulwich , South London. The gallery, designed by Regency architect Sir John Soane using an innovative and influential method of illumination, opened to the public in 1817. It is the oldest public art gallery in England and was made an independent charitable trust in 1994. Until this time the gallery was part of Alleyn's College of God's Gift , a charitable foundation established by the actor, entrepreneur and philanthropist Edward Alleyn in the early-17th century. The art gallery was designed in 1811 by British architect John Soane and claims to be the world's first purpose-built public art gallery. It features facades of London stock brick with Portland stone detailing. The pavilion was commissioned by the Dulwich Picture Gallery and property development firm Almacantar for the London Festival of Architecture, which kicks off on 1 June and will continue all month. IF_DO worked with engineers StructureMode and fabricators Weber Industries on the 192-square-metre structure, which was completed in just one month and cost £110,000. -

Who's Who in the Marlowe Chronology

Who’s Who in the Marlowe Chronology Agrippa, Heinrich Cornelius. Supposed magician and author of several books; a possible influence on Doctor Faustus. Aldrich, Simon. Canterbury and Cambridge man who tells an anecdote about Marlowe and ‘Mr Fineux’ (see under 1641). Allen, William, Cardinal. Responsible for the imprisonment of Richard Baines at Douai (see under 1582). Alleyn, Edward. Actor. Took the leading rôle in Tamburlaine, The Jew of Malta and Doctor Faustus. Alleyn, John. Brother of Edward. Arthur, Dorothy. Marlowe’s cousin, who came to live with his family after she was orphaned. Arthur, Thomas. Marlowe’s maternal uncle. Babington, Anthony. Catholic conspirator entrapped by Robert Poley (see under 1586). Baines, Richard. Studied at Douai; detained with Marlowe in Flushing for coining (see under 26 January 1592); author of the ‘Note’ alleging that Marlowe held heretical opinions (see under 26 May 1593). Ballard, John. One of the Babington conspirators (see under 1586). Benchkin, John. Canterbury and Cambridge man who may have been a friend of Marlowe’s. Blount, Christopher. Catholic and eventual stepfather of the Earl of Essex; on the fringes of a number of big political events. His mother was a Poley so he may have been connected with Robert Poley. Bridgeman, Jacob. Marlowe’s successor as Parker Scholar. Bruno, Giordano. Author; eventually burned for heresy; probably the source of the name ‘Bruno’ in Doctor Faustus. Bull, Eleanor. Owner of the house in which Marlowe died. Catlin, Maliverny. Walsingham agent provocateur. Cecil, John. Catholic priest and possible double agent (see under 1590). Chapman, George. Playwright and apparent friend of Marlowe; completed Hero and Leander. -

Before Shakespeare: the Drama of the 1580S Andy Kesson (University of Roehampton)

Before Shakespeare: The Drama of the 1580s Andy Kesson (University of Roehampton) Beioley "Who is it that knowes me not by my partie coloured head?": Playing the Vice in the 1580s Abstract: The 1580s is a significant decade for the Vice tradition, as it is conventionally regarded as the period in which allegorical drama declined, and therefore as heralding the decline of the “proper” Vice figure. As Alan Dessen has noted, “Most scholars accept Bernard Spivack’s formulation that, except for an occasional throwback, the period after 1590 ‘marks the dead end and dissolution of the allegorical drama, at least on the popular stage’” (Allegorical Action and Elizabethan Staging 391). In the conception of those who follow Spivack's thinking, then, the 1580s can thus be seen as the crossroads between the more allegorical Vices of Tudor drama, and later characters like Richard of Gloucester who embody or evoke some of the Vice's characteristics, often while drawing attention to this influence as Richard himself does: “Thus, like the formal Vice, Iniquity, / I moralize two meanings in one word.” Such borders, however, are never neat, and in this paper I will challenge this somewhat teleological portrayal of the Vice's development through an examination of the 1581 play The Three Ladies of London, and its 1588 “sequel” The Three Lords and Three Ladies of London, and consider the ways in which the 1580s affected the expression of the Vice figure as it continued to develop and change. Dessen, Alan C. "Allegorical Action and Elizabethan Staging." Studies in English Literature, 1500- 1900. -

The Case of John Fletcher and Philip Massinger's Love's Cure

This is a repository copy of What the Quills Can Tell: The Case of John Fletcher and Philip Massinger’s Love’s Cure. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/113584/ Version: Accepted Version Book Section: Perez Diez, JA orcid.org/0000-0003-0227-8965 (2017) What the Quills Can Tell: The Case of John Fletcher and Philip Massinger’s Love’s Cure. In: Holland, P, (ed.) Shakespeare Survey 70: Creating Shakespeare. Shakepeare Survey, 70 . Cambridge University Press , Cambridge, UK , pp. 89-98. ISBN 9781108277648 https://doi.org/10.1017/9781108277648.010 (c) Cambridge University Press 2017. This material has been published in Shakespeare Survey 70, edited by Holland, P This version is free to view and download for personal use only. Not for re-distribution, re-sale or use in derivative works. Reuse Items deposited in White Rose Research Online are protected by copyright, with all rights reserved unless indicated otherwise. They may be downloaded and/or printed for private study, or other acts as permitted by national copyright laws. The publisher or other rights holders may allow further reproduction and re-use of the full text version. This is indicated by the licence information on the White Rose Research Online record for the item. Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ What the quills can tell: the case of John Fletcher and Philip Massinger’s Love’s Cure José A.