The Case of John Fletcher and Philip Massinger's Love's Cure

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Early Modern Piracy 1/8

MS Early Modern Piracy 1/8 Corsairs, Privateers, Renegados: Early Modern Piracy Syllabus Let’s get this out of the way: Like the last two terms, summer term 201 will be yet another experiment in pandemic pedagogics. I look forward to experimenting with new forms of (online) teaching, but I will need your help. Please keep in touch, take part in the Zoom classes, and use the forum for asynchronous coursework (study questions, book reviews – tasks specified below). Most importantly, please let me (and the other course members) know if something does not work for you or if you have different ideas about how to do things. Let’s do this together! class: - Wednesday, 16:15-17:45 [online] As Zoom is not the perfect medium for everyone (and some of you might struggle with technical issues) the seminar will combine synchronous Zoom classes and asynchronous sessions (see schedule & tasks below). contact: - [office: 4.154 IG-Farben-Haus] - e-mail: - office hours: Thursday, 9:00-10:30 (and on appointment) – please send me an e-mail for the Zoom link. - twitter: @susannegruss (#PiracyMS) resources: - OLAT: literature: - Please buy and read the following primary texts (listed in the order of discussion in class): (1) George Peele, The Battle of Alcazar () (in The Stukeley Plays, Revels Plays, Manchester UP); The Life and Death of the Famous Thomas Stukely (broadside ballad, c.1693-96, http://ebba.english.ucsb.edu/search_combined/?ss=thomas+stukely) (2) Thomas Heywood & Philip Rowley, Fortune by Land and Sea (1607-09) (copy on OLAT) (3) John Fletcher and Philip Massinger, The Double Marriage (c.1619-22) (copy on OLAT) (4) Philip Massinger, The Renegado (1624) (Arden Early Modern Drama) - All other texts that are mandatory reading are available on OLAT. -

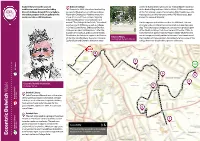

Eccentric Dulwich Walk Eccentric and Exit Via the Old College Gate

Explore Dulwich and its unusual 3 Dulwich College writer; Sir Edward George (known as “Steady Eddie”, Governor architecture and characters including Founded in 1619, the school was built by of the Bank of England from 1993 to 2003); C S Forester, writer Dulwich College, Dulwich Picture Gallery - successful Elizabethan actor Edward Alleyn. of the Hornblower novels; the comedian, Bob Monkhouse, who the oldest purpose-built art gallery in the Playwright Christopher Marlowe wrote him was expelled, and the humorous writer PG Wodehouse, best world, and Herne Hill Velodrome. some of his most famous roles. Originally known for Jeeves & Wooster. meant to educate 12 “poor scholars” and named “The College of God’s Gift,” the school On the opposite side of the road lies The Mill Pond. This was now has over 1,500 boys, as well as colleges originally a clay pit where the raw materials to make tiles were in China & South Korea. Old boys of Dulwich dug. The picturesque cottages you can see were probably part College are called “Old Alleynians”, after the of the tile kiln buildings that stood here until the late 1700s. In founder of the school, and include: Sir Ernest 1870 the French painter Camille Pissarro (1830-1903) fled the Shackleton, the Antarctic explorer; Ed Simons war in Europe and briefly settled in the area. Considered one of Edward Alleyn, of the Chemical Brothers; the actor, Chiwetel the founders of Impressionism, he painted a famous view of the photograph by Sara Moiola Ejiofor; Raymond Chandler, detective story college from here (now held in a private collection). -

Bibliography

206 Fletcherian Dramatic Achievement Bibliography Primary sources Apology for Actors Thomas Dekker, An Apology for Actors (1612), ed. Richard H. Per- kinson, New York 1941 Aristotle Poetics, tr. W. Hamilton Fyfe, The Loeb Classics Library, Cam- bridge, Mass., London 1927 St Augustine St Augustine, The Teacher, in Against the Academicians; and, The Teach- er, trans. Peter King, Indianapolis, Cambridge 1995 Bellenden The Chronicles of Scotland: Compiled by Hector Boece: Translated into Scots by John Bellenden, 1531, ed. R. W. Chambers and Edith C. Batho, vol. I, Edinburgh and London 1938 Bowers I-X The Dramatic Works in the Beaumont and Fletcher Canon, gen. ed. Fredson Bowers, 10 vols, Cambridge UP 1966–1996 [Cicero] Ad Herennium, tr. Harry Caplan; The Loeb Classical Library, Cambridge, Mass., London 1954 Demetrius and Enanthe MS John Fletcher, Demetrius and Enanthe, ed. Margaret McLaren Cook and F. P. Wilson, The Malone Society Reprints 1950 (1951) Dio Dio Cassius, Dio’s Roman History, tr. Earnest Cary, vol. vii, The Loeb Classical Library, Cambridge, Mass., London 1961 Faithful Friends The Faithful Friends, ed. G. R. Proudfoot and G. M. Pinciss, The Malone Society Reprints 1970 (1975) Henslowe’s Diary Henslowe’s Diary, ed. R. A. Foakes, 2nd edition, Cambridge UP 2002. Howard-Hill (1980) Sir John Van Olden Barnavelt: by John Fletcher and Philip Massinger, ed. T. H. Howard-Hill, The Malone Society Reprints 1979 (1980) Bonduca MS Bonduca: by John Fletcher, ed. W. W. Greg, The Malone Society Re- prints, 1951 Mann Thomas Mann, Doctor Faustus, tr. H. T. Lowe-Porter, Everyman’s Library, vol.80, 1992 Masque of Queens Ben Jonson, The Masque of Queens (1609), published in his Workes (1616): 945–964 Meres Francis Meres, Palladis Tamia (1598), Scholars’ Facsimiles & Re- prints, New York 1938 Metrical Boece (1858) The Buik of the Chroniclis of Scotland; or, A Metrical Version of the History of Hector Boece; By William Stewart (1535), ed. -

The Edward Alleyn Golf Society, It Was for Me Immensely Enjoyable in My Own 49Th Year

T he Edward Alleyn G olf Society (Established 1968) Hon. Secretary: President: Dr Gary Savage MA PhD George Thorne Past Presidents: Sir Henry Cotton KCMG MBE 4 Bell Meadow Derek Fenner MA London Dr Colin Niven OBE SE19 1HP Dr Colin Diggory MA EdD [email protected] Tel: 0208 488 7828 The Society Christmas Dinner and Annual General Meeting will be held on Friday 8th December 2017 at Dulwich & Sydenham Hill GC, commencing with a drinks reception at 19:00. Present: Vince Abel, Steve Bargeron, Peter Battle, James Bridgeman, Tracy Bridgeman, Dave Britton, Roger Brunner, Andre Cutress, Roger Dollimore, Neil Hardwick, Perry Harley, Bob Joyce, John Knight, Dennis Lomas, Alan Miles, Roger Parkinson, Ted Pearce, Steve Poole, Jack Roberts, Keith Rodwell, John Smith, Ray Stiles, Justin Sutton, George Thorne, Tim Wareham, Alan Williams, Anton Williams; Guests: John Battle, Roy Croft, Neil French, Chris Nelson. Apologies: Mikael Berglund, Chris Briere-Edney, Trevor Cain, Dave Cleveland, Dom Cleveland, Len Cleveland, John Coleman, John Dunley, Dr Colin Diggory MA,EdD, John Etches, Ray Eyre, David Foulds, Mike Froggatt, Mark Gardner, David Hankin, Peter Holland, Bruce Leary, Dave McEvoy, Dave Sandars, Andrew Saunders, Paul Selwyn, Dave Slaney, Chris Shirtcliffe, Dr Gary Savage MA,PhD. In Memoriam A minute’s silence in memory of Society Members and other Alumni who have passed away this year : Kit Miller, attended 10 meetings between 1976 and 1991; Jim Calvo, attended 11 meetings and many tours between 2001 and 2015; Steve Crosby, attended 2 meetings in 1993-4; Brian Romilly non-golfer, but a great friend of many of our members. -

From Sidney to Heywood: the Social Status of Commercial Theatre in Early Modern London

From Sidney to Heywood: the social status of commercial theatre in early modern London Romola Nuttall (King’s College London, UK) The Literary London Journal, Volume 14 Number 1 (Spring 2017) Abstract Thomas Heywood’s Apology for Actors (written c. 1608, published 1612) is one of the only stand-alone, printed deFences of the proFessional theatre to emerge from the early modern period. Even more significantly, it is ‘the only contemporary complete text we have – by an early modern actor about early modern actors’ (Griffith 191). This is rather surprising considering how famous playwrights and drama of that period have become, but it is revealing of attitudes towards the profession and the stage at the turn of the sixteenth century. Religious concerns Formed a central part of the heated public debate which contested the social value oF proFessional drama during the early modern era. Claims against the literary status of work produced for the commercial stage were also frequently levelled against the theatre from within the establishment, a prominent example being Sir Philip Sidney’s Defence of Poesie (written c. 1579, published 1595). Considering Heywood’s Apology in relation to Sidney’s Defence, and thinking particularly about the ways these treatises appropriate the classical idea oF mimesis and the consequent social value of literature, gives fresh insight into the changing status of drama in Shakespeare’s lifetime and how attitudes towards commercial theatre developed between the 1570s and 1610s. The following article explores these ideas within the framework of the London in which Heywood and his acting company lived and worked. -

A Noise Within Study Guide Shakespeare Supplement

A Noise Within Study Guide Shakespeare Supplement California’s Home for the Classics California’s Home for the Classics California’s Home for the Classics Table of Contents Dating Shakespeare’s Plays 3 Life in Shakespeare’s England 4 Elizabethan Theatre 8 Working in Elizabethan England 14 This Sceptered Isle 16 One Big Happy Family Tree 20 Sir John Falstaff and Tavern Culture 21 Battle of the Henries 24 Playing Nine Men’s Morris 30 FUNDING FOR A NOISE WITHIN’S EDUCATIONAL PROGRAMS IS PROVIDED IN paRT BY: The Ahmanson Foundation, Alliance for the Advancement of Arts Education, Supervisor Michael D. Antonovich, Employees Community Fund of Boeing California, The Capital Group Companies, Citigroup Foundation, Disney Worldwide Outreach, Doukas Family Foundation, Ellingsen Family Foundation, The Herb Alpert Foundation, The Green Foundation, Kiwanis Club of Glendale, Lockheed Federal Credit Union, Los Angeles County Arts Commission, B.C. McCabe Foundation, Metropolitan Associates, National Endowment for the Arts, The Kenneth T. and Eileen L. Norris Foundation, The Steinmetz Foundation, Dwight Stuart Youth Foundation, Waterman Foundation, Zeigler Family Foundation. 2 A Noise Within Study Guide Shakespeare Supplement Dating Shakespeare’s Plays Establishing an exact date for the Plays of Shakespeare. She theorized that authorship of Shakespeare’s plays is a very Shakespeare (a “stupid, ignorant, third- difficult task. It is impossible to pin down rate play actor”) could not have written the exact order, because there are no the plays attributed to him. The Victorians records giving details of the first production. were suspicious that a middle-class actor Many of the plays were performed years could ever be England’s greatest poet as before they were first published. -

Future School Guidance

FUTURE SCHOOL GUIDANCE Choosing the right senior school for your son Introduction This guide is designed to help you to identify the right future school for your son. Dulwich Prep London has an excellent record of sending boys to some of the best senior schools in the country, but even more important than that record is helping each and every one of our families to find the right school for their son. With so much choice available and so many different matters to consider, this is not always easy to do, but we are here to help you. Our experienced team will use their expertise, knowledge about the future school options, and critically our understanding of the type of environment in which your son will thrive to inform you about the possible and the best options. We will be ambitious but also candid with this advice to ensure that you have a realistic appraisal of the options that you might consider. We will need to work in partnership throughout the journey, and be flexible enough to adjust as your son develops. The Head Master and the Deputy Head (Tracking and Transition) lead the school team in this regard. In turn, they draw upon the advice of the team of staff supporting your son to achieve his potential. This team includes: Head of Section Head of Year Tutor (please always ensure that your son’s tutor is copied into all emails) Subject Teachers Specialist Teachers SEND Teachers (where applicable) Throughout this process, we will support your son and prioritise his wellbeing. -

History (Maternity Cover) JD 20-21.Indd

AAlleyn’slleyn’s AAppointmentppointment ooff TTeachereacher ooff HHistoryistory ((MaternityMaternity CCover)over) ffromrom AAprilpril 22021021 ttoo MMarcharch 22022022 IInformationnformation fforor AApplicantspplicants JJanuaryanuary 22021021 Teacher of History (Maternity Cover) From April 2021to April 2022 Alleyn’s is one of the country’s leading co-educa onal independent day schools, commi ed to developing excellence within an ethos of strong pastoral care and a vibrant co-curriculum. Our holis c approach aims to nurture every pupil, enabling them to develop their poten al while making friendships and enjoying life to the full. We believe that learning together in a suppor ve environment provides the best framework for boys and girls to excel at school, to discover new ideas, skills and enthusiasms and to prepare for university and the mul -gendered world of work and life in general. Links with local and overseas schools, universi es and chari es provide further opportuni es to enrich that learning in diff erent contexts and to make new and las ng friends. Our community is warm, caring and inclusive and we are very proud of our pupils, who leave us with excellent examina on results, places at some of the world’s top universi es and specialist centres of higher educa on, and with a sense of confi dence, mutual respect and social responsibility. We greatly value our commi ed and hard-working staff , whose dedica on makes possible the achievements of our pupils. Our Vision Alleyn’s is a happy and successful co-educa onal and academically -

Anglo-Jewry's Experience of Secondary Education

Anglo-Jewry’s Experience of Secondary Education from the 1830s until 1920 Emma Tanya Harris A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements For award of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Hebrew and Jewish Studies University College London London 2007 1 UMI Number: U592088 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U592088 Published by ProQuest LLC 2013. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 Abstract of Thesis This thesis examines the birth of secondary education for Jews in England, focusing on the middle classes as defined in the text. This study explores various types of secondary education that are categorised under one of two generic terms - Jewish secondary education or secondary education for Jews. The former describes institutions, offered by individual Jews, which provided a blend of religious and/or secular education. The latter focuses on non-Jewish schools which accepted Jews (and some which did not but were, nevertheless, attended by Jews). Whilst this work emphasises London and its environs, other areas of Jewish residence, both major and minor, are also investigated. -

Capaok Cortes.Indd

Tiff any Stern, ‘Repatching the Play’ 1 Tiff any Stern Oxford University Theatre histories often explore the context surrounding the creation of the play. Was there one author or many? Did the physical make up of the theatre or the company shape the production of the work? Each of these topics importantly helps defi ne the world that brought about the text. But despite the huge interest in what shaped the play, the nature of the play itself is less often questioned. The unity of a play is often taken as a given; articles on the revising of play texts tend to assume that one whole and complete text was equally revised over by its author. Why, it is then asked, did playwrights bother to write long plays that would then have to be cut and rewritten in the playhouse itself? By exploring the fragmentary nature of the text, an answer to that question can be suggested. The designation ‘playwright’ seems to have come into being in the 1610s.2 With its implications of writing plays as a trade – playwright obviously relating to such jobs as cartwright and wheelwright – ‘playwright’ was probably, as a title, originally pejorative. There were other more common and neutral words to describe the profession. One – the most usual – was ‘poet’, telling in itself with its implication that all plays are or should be in verse. Another less hierarchical term was ‘play- maker’, a simple description of the task of writing plays. A fourth title has not been critically noticed, or at least not for what it implies. -

Young-Art-Catalogue-2016 06-1.Pdf

A DIFFERENT VIEWPOINT Tuesday 26 April – Friday 29 April Royal College of Art YOUNG ART 2016 Every child is an artist. The problem is how to remain ONCE A STAIRCASE. an artist once he grows up. NOW A STROLL —Pablo Picasso THROUGH HISTORY. As your home becomes more important, CONTENTS so does your insurer. A Year to Remember 2 A Different Viewpoint 3 About Young Art 4 Welcome 5 Thank You 7 Behind the Microscope 8 Dr Tessa Kasia A Word from the Rector 11 Dr Paul Thompson Young Art in Schools 14 Sir Christopher Frayling 16 Meet the Judges 18 A Day in the Life of a Framer 39 Silent Auction 40 Quiz 42 Acknowledgments 62 Catalogue compiled and edited by Maria Howard Home Insurance with contributions from Kate Dilnott-Cooper and India Jaques. Design by Clover Stevens. hiscox.co.uk Artwork photography by Charlie Milligan Cover by Nick Goodwin 1 Hiscox Underwriting Ltd is authorised and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority. 15740 04/16 YOUNG ART 2016 A YEAR TO REMEMBER Last year we celebrated the 25th anniversary of the first Young Art exhibition by raising £89,200 for Cancer Research UK. With a record number of 8,300 entries submitted and 760 on display at the Royal College of A DIFFERENT VIEWPOINT Art, it was an exceptional showcase of children’s art. Tuesday 26 April – Friday 29 April Royal College of Art Everyone at YA would like to say an Kensington Gore, London SW7 2EU enormous thank you to all the people who made it happen – exhibitors, teachers, schools, parents, judges – Featuring works donated by leading contemporary artists and all our supporters who gave so and Royal Academicians, supporting Cancer Research UK generously to such an important cause. -

Newsletter #104 (Spring 1995)

The Dulwich Society - Newsletter 104 Spring - 1995 Contents What's on 1 Dulwich Park 13 Annual General Meeting 3 Wildlife 14 Obituary: Ronnie Reed 4 The Watchman Tree 16 Conservation Trust 7 Edward Alleyn Mystery 20 Transport 8 Letters 35 Chairman Joint Membership Secretaries Reg Collins Robin and Wilfrid Taylor 6 Eastlands Crescent, SE21 7EG 30 Walkerscroft Mead, SE21 81J Tel: 0181-693 1223 Tel: 0181-670 0890 Vice Chairman Editor W.P. Higman Brian McConnell 170 Burbage Road, SE21 7AG 9 Frank Dixon W1y, SE2 I 7ET Tel: 0171-274 6921 Tel & Fax: 0181-693 4423 Secretary Patrick Spencer Features Editor 7 Pond Cottages, Jane Furnival College Road, SE21 7LE 28 Little Bornes, SE21 SSE Tel: 0181-693 2043 Tel: 0181-670 6819 Treasurer Advertising Manager Russell Lloyd Anne-Maree Sheehan 138 Woodwarde Road, SE22 SUR 58 Cooper Close, SE! 7QU Tel: 0181-693 2452 Tel: 0171-928 4075 Registered under the Charities Act 1960 Reg. No. 234192 Registered with the Civic Trust Typesetting and Printing: Postal Publicity Press (S.J. Heady & Co. Ltd.) 0171-622 2411 1 DULWICH SOCIETY EVENTS NOTICE is hereby given that the 32nd Annual General Meeting of The 1995 Dulwich Society will be held at 8 p.m. on Friday March 10 1995 at St Faith's Friday, March 10. Annual General Meeting, St Faith's Centre, Red Post Hill, Community and Youth Centre, Red Post Hill, SE24 9JQ. 8p.m. Friday, March 24. Illustrated lecture, "Shrubs and herbaceous perennials for AGENDA the spring" by Aubrey Barker of Hopley's Nurseries. St Faith's Centre.