"A Sharers' Repertory." Rethinking Theatrical

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Shakespeare Wrote Shakespeare

OPEN FORUM The Pages of The Oxfordian are open to all sides of the Authorship Question Shakespeare Wrote Shakespeare David Kathman or the vast majority of Shake- speare scholars, there is no ‘au- thorship question’; they agree that F the works of William Shake- speare were written by William Shake- speare of Stratford-upon-Avon (allow- ing for some collaboration), and tend to ignore or dismiss anyone who claims oth- erwise. In the following pages I will try to explain, from the perspective of a Shake- speare scholar, why the Stratford Shakespeare’s authorship is so generally ac- cepted by historians, and why those historians do not take seriously the various attempts to deny that attribution. I realize from experience that this explanation is not likely to convince many committed antistratfordians, but at the very least I hope to correct some misconceptions about what Shakespeare scholars actually believe. For the purposes of argument, we can distinguish among three main strands of William Shakespeare’s biography, which I will call Stratford Shakespeare, Actor Shakespeare, and Author Shakespeare. Stratford Shakespeare was baptized in Stratford-upon-Avon in 1564, married Anne Hathaway in 1582, had three children with her, bought New Place in 1597 and various other properties in and around Stratford over the following decade, and was buried in there in 1616. Actor Shakespeare was a member of the Lord Chamberlain’s/King’s Men, the leading acting company in London from 1594 on, and an original sharer in the Globe and Blackfriars playhouses. Author Shakespeare signed the dedications of Venus and Adonis (1593) and The Rape of Lucrece (1594), and over the next twenty years was named on title 13 THE OXFORDIAN Volume XI 2009 Kathman pages as the author of numerous plays and poems, and was praised by such crit- ics as Francis Meres and Gabriel Harvey. -

THE ALCHEMIST THROUGH the AGES an Investigation of the Stage

f [ THE ALCHEMIST THROUGH THE AGES An investigation of the stage history of Ben Jonson's play by JAMES CUNNINGHAM CARTER B.Sc., University of British Columbia, 196 8 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT. OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in the Department of English We accept this thesis as conforming to the required standard THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA October 1972 In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for an advanced degree at the University of British Columbia, I agree that the Library shall make it freely available for reference and study. I further agree that permission for extensive copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by the Head of my Department or by his representatives. It is understood that copying or publication of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. Department of The University of British Columbia Vancouver 8, Canada Date 27 QclAtt ii ABSTRACT THE ALCHEMIST THROUGH THE AGES An Investigation of the Stage History of Ben Jonson's Play This study was made to trace the stage history of The Alchemist and to see what effect theatrical productions can have in developing critical awareness of Jonson's dramatic skill in this popular play. Therefore an attempt has been made to record all performances by major companies between 1610 and 197 0 with cast lists and other pertinent information about scenery/ stage action and properties. The second part of the thesis provides a detailed analysis of four specific productions considered in light of their prompt books, details of acting and production, and overall critical reception. -

SCN 72 3&4 2014.Pdf (656.7Kb)

EVENTEENTH- ENTURY EWS FALL - WINTER 2014 Vol. 72 Nos. 3&4 Including THE NEO-LATIN NEWS Vol. 62, Nos. 3&4 SEVENTEENTH-CENTURY NEWS VOLUME 72, Nos. 3&4 FALL-WINTER, 2014 An official organ of the Milton Society of America and of the Milton Section of the Modern Language Association, SCN is published as a double issue two times each year with the support of the English Department at Texas A&M University. SUBMISSIONS: As a scholarly review journal, SCN publishes only commissioned reviews. As a service to the scholarly community, SCN also publishes news items. A current style sheet, previous volumes’ Tables of Contents, and other informa- tion all may be obtained via at www.english.tamu.edu/scn/. Books for review and queries should be sent to: Prof. Donald R. Dickson English Department 4227 Texas A&M University College Station, Texas 77843-4227 E-Mail: [email protected] www.english.tamu.edu/scn/ and journals.tdl.org/scn ISSN 0037-3028 SEVENTEENTH-CENTURY NEWS EDITOR DONALD R. DICKSON Texas A&M University ASSOCIATE EDITORS Michele Marrapodi, University of Palermo Patricia Garcia, University of Texas E. Joe Johnson, Clayton State University EDITORIAL ASSISTANT Megan Pearson, Texas A&M University Morgan Wilson, Texas A&M University CONTENTS VOLUME 72, NOS. 3&4 ................................ FALL-WINTER, 2014 reviews Tom Cain and Ruth Connolly, eds., The Complete Poetry of Robert Herrick. Review by james mardock and eric rasmussen ........................... 190 Siobhán Collins, Bodies, Politics and Transformations: John Donne’s Metempsychosis. Review by anne lake prescott .......................... 195 Nabil Matar, Henry Stubbe’s The Rise and Progress of Mahometanism. -

Proem Shakespeare S 'Plaies and Poems"

Proem Shakespeare s 'Plaies and Poems" In 1640, the publisher John Benson presents to his English reading public a Shakespeare who is now largely lost to us: the national author of poems and plays. By printing his modest octavo edition of the Poems: Written By Wil. Shake-speare. Gent., Benson curiously aims to complement the 1623 printing venture of Shakespeare's theatre colleagues, John Heminge and Henry Condell , who had presented Mr. William Shakespeares Comedies, Histories, & Tragedies in their monumental First Folio. Thus, in his own Dedicatory Epistle "To the Reader," Benson remarks that he presents "some excellent and sweetly composed Poems," which "had nor the fortune by reason of their lnfancie in his death, to have the due accommodation of proportionable glory, with the rest of his everliving Workes" (*2r). Indeed, as recent scholarship demonstrates, Benson boldly prints his octavo Poems on the model ofHeminge and Condell 's Folio Plays. ' Nor simply does Benson's volume share its primer, Thomas Cores, wirh rhe 1632 Folio, bur both editions begin with an identical format: an engraved portrait of the author; a dedicatory epistle "To the Reader"; and a set of commendatory verses, with Leonard Digges contributing an impor tant celebratory poem to both volumes. Benson's engraving by William Marshall even derives from the famous Martin Droeshout engraving in the First Folio, and six of the eight lines beneath Benson's engraving are borrowed from Ben Jonson's famed memorial poem to Shakespeare in char volume. Accordingly, Benson rakes his publishing goal from Heminge and Conde!!. They aim to "keepe the memory of such worthy a Friend, & Fellow alive" (Dedicatory Epistle to the earls ofPembroke and Montgomery, reprinted in Riverside, 94), while he aims "to be serviceable for the con tinuance of glory to the deserved Author" ("To the Reader," *2v). -

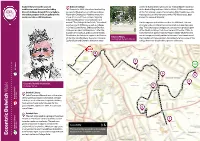

Eccentric Dulwich Walk Eccentric and Exit Via the Old College Gate

Explore Dulwich and its unusual 3 Dulwich College writer; Sir Edward George (known as “Steady Eddie”, Governor architecture and characters including Founded in 1619, the school was built by of the Bank of England from 1993 to 2003); C S Forester, writer Dulwich College, Dulwich Picture Gallery - successful Elizabethan actor Edward Alleyn. of the Hornblower novels; the comedian, Bob Monkhouse, who the oldest purpose-built art gallery in the Playwright Christopher Marlowe wrote him was expelled, and the humorous writer PG Wodehouse, best world, and Herne Hill Velodrome. some of his most famous roles. Originally known for Jeeves & Wooster. meant to educate 12 “poor scholars” and named “The College of God’s Gift,” the school On the opposite side of the road lies The Mill Pond. This was now has over 1,500 boys, as well as colleges originally a clay pit where the raw materials to make tiles were in China & South Korea. Old boys of Dulwich dug. The picturesque cottages you can see were probably part College are called “Old Alleynians”, after the of the tile kiln buildings that stood here until the late 1700s. In founder of the school, and include: Sir Ernest 1870 the French painter Camille Pissarro (1830-1903) fled the Shackleton, the Antarctic explorer; Ed Simons war in Europe and briefly settled in the area. Considered one of Edward Alleyn, of the Chemical Brothers; the actor, Chiwetel the founders of Impressionism, he painted a famous view of the photograph by Sara Moiola Ejiofor; Raymond Chandler, detective story college from here (now held in a private collection). -

The Edward Alleyn Golf Society, It Was for Me Immensely Enjoyable in My Own 49Th Year

T he Edward Alleyn G olf Society (Established 1968) Hon. Secretary: President: Dr Gary Savage MA PhD George Thorne Past Presidents: Sir Henry Cotton KCMG MBE 4 Bell Meadow Derek Fenner MA London Dr Colin Niven OBE SE19 1HP Dr Colin Diggory MA EdD [email protected] Tel: 0208 488 7828 The Society Christmas Dinner and Annual General Meeting will be held on Friday 8th December 2017 at Dulwich & Sydenham Hill GC, commencing with a drinks reception at 19:00. Present: Vince Abel, Steve Bargeron, Peter Battle, James Bridgeman, Tracy Bridgeman, Dave Britton, Roger Brunner, Andre Cutress, Roger Dollimore, Neil Hardwick, Perry Harley, Bob Joyce, John Knight, Dennis Lomas, Alan Miles, Roger Parkinson, Ted Pearce, Steve Poole, Jack Roberts, Keith Rodwell, John Smith, Ray Stiles, Justin Sutton, George Thorne, Tim Wareham, Alan Williams, Anton Williams; Guests: John Battle, Roy Croft, Neil French, Chris Nelson. Apologies: Mikael Berglund, Chris Briere-Edney, Trevor Cain, Dave Cleveland, Dom Cleveland, Len Cleveland, John Coleman, John Dunley, Dr Colin Diggory MA,EdD, John Etches, Ray Eyre, David Foulds, Mike Froggatt, Mark Gardner, David Hankin, Peter Holland, Bruce Leary, Dave McEvoy, Dave Sandars, Andrew Saunders, Paul Selwyn, Dave Slaney, Chris Shirtcliffe, Dr Gary Savage MA,PhD. In Memoriam A minute’s silence in memory of Society Members and other Alumni who have passed away this year : Kit Miller, attended 10 meetings between 1976 and 1991; Jim Calvo, attended 11 meetings and many tours between 2001 and 2015; Steve Crosby, attended 2 meetings in 1993-4; Brian Romilly non-golfer, but a great friend of many of our members. -

From Sidney to Heywood: the Social Status of Commercial Theatre in Early Modern London

From Sidney to Heywood: the social status of commercial theatre in early modern London Romola Nuttall (King’s College London, UK) The Literary London Journal, Volume 14 Number 1 (Spring 2017) Abstract Thomas Heywood’s Apology for Actors (written c. 1608, published 1612) is one of the only stand-alone, printed deFences of the proFessional theatre to emerge from the early modern period. Even more significantly, it is ‘the only contemporary complete text we have – by an early modern actor about early modern actors’ (Griffith 191). This is rather surprising considering how famous playwrights and drama of that period have become, but it is revealing of attitudes towards the profession and the stage at the turn of the sixteenth century. Religious concerns Formed a central part of the heated public debate which contested the social value oF proFessional drama during the early modern era. Claims against the literary status of work produced for the commercial stage were also frequently levelled against the theatre from within the establishment, a prominent example being Sir Philip Sidney’s Defence of Poesie (written c. 1579, published 1595). Considering Heywood’s Apology in relation to Sidney’s Defence, and thinking particularly about the ways these treatises appropriate the classical idea oF mimesis and the consequent social value of literature, gives fresh insight into the changing status of drama in Shakespeare’s lifetime and how attitudes towards commercial theatre developed between the 1570s and 1610s. The following article explores these ideas within the framework of the London in which Heywood and his acting company lived and worked. -

A Noise Within Study Guide Shakespeare Supplement

A Noise Within Study Guide Shakespeare Supplement California’s Home for the Classics California’s Home for the Classics California’s Home for the Classics Table of Contents Dating Shakespeare’s Plays 3 Life in Shakespeare’s England 4 Elizabethan Theatre 8 Working in Elizabethan England 14 This Sceptered Isle 16 One Big Happy Family Tree 20 Sir John Falstaff and Tavern Culture 21 Battle of the Henries 24 Playing Nine Men’s Morris 30 FUNDING FOR A NOISE WITHIN’S EDUCATIONAL PROGRAMS IS PROVIDED IN paRT BY: The Ahmanson Foundation, Alliance for the Advancement of Arts Education, Supervisor Michael D. Antonovich, Employees Community Fund of Boeing California, The Capital Group Companies, Citigroup Foundation, Disney Worldwide Outreach, Doukas Family Foundation, Ellingsen Family Foundation, The Herb Alpert Foundation, The Green Foundation, Kiwanis Club of Glendale, Lockheed Federal Credit Union, Los Angeles County Arts Commission, B.C. McCabe Foundation, Metropolitan Associates, National Endowment for the Arts, The Kenneth T. and Eileen L. Norris Foundation, The Steinmetz Foundation, Dwight Stuart Youth Foundation, Waterman Foundation, Zeigler Family Foundation. 2 A Noise Within Study Guide Shakespeare Supplement Dating Shakespeare’s Plays Establishing an exact date for the Plays of Shakespeare. She theorized that authorship of Shakespeare’s plays is a very Shakespeare (a “stupid, ignorant, third- difficult task. It is impossible to pin down rate play actor”) could not have written the exact order, because there are no the plays attributed to him. The Victorians records giving details of the first production. were suspicious that a middle-class actor Many of the plays were performed years could ever be England’s greatest poet as before they were first published. -

John Heminges's Tap-House at the Globe the Theatre Profession Has A

Untitled Document John Heminges's Tap-house at the Globe The theatre profession has a long association with catering and victualling. Richard Tarlton, the leading English comic actor of the late sixteenth century, ran a tavern in Gracechurch Street and an eating house in Paternoster Row (Nungezer 1929, 354); and W. J. Lawrence found a picture of Tarlton serving food to four merchants in his establishment (Lawrence 1937, 17-38). John Heminges, actor-manager in Shakespeare's company, appears to have continued the tradition by selling alcohol at a low-class establishment directly attached to the Globe playhouse. Known as a tap-house or ale-house, this kind of shop differed from the more prestigious inns and taverns in selling only beer and ale (no wine) and offering only the most basic food and accommodation (Clark 1983, 5). Presumably at the Globe most customers were expected to take their drinks into the playhouse. The hard evidence for Heminges's tap-house is incomplete and fragmented. Augustine Phillips, a King's man, died in May 1605 and his widow Anne married John Witter. Phillips's will designated Heminges as executor in the event of Anne's remarriage (Honigmann & Brock 1992, 74) and in this capacity Heminges leased the couple an interest in the Globe (Chambers 1923, 418; Wallace 1910, 319). When the Globe had to be rebuilt after the fire of 1613, the Witters could not afford their share and the ensuing case ("Witter versus Heminges and Condell" in the Court of Requests 1619-20) left valuable evidence about the organization of the playhouse syndicate. -

Notes on the Bacon-Shakespeare Question

NOTES ON THE BACON-SHAKESPEARE QUESTION BY CHARLES ALLEN BOSTON AND NEW YORK HOUGHTON, MIFFLIN AND COMPANY ftiucrsi&c press, 1900 COPYRIGHT, 1900, BY CHARLES ALLEN ALL RIGHTS RESERVED GIFT PREFACE AN attempt is here made to throw some new light, at least for those who are Dot already Shakespearian scholars, upon the still vexed ques- tion of the authorship of the plays and poems which bear Shakespeare's name. In the first place, it has seemed to me that the Baconian ar- gument from the legal knowledge shown in the plays is of slight weight, but that heretofore it has not been adequately met. Accordingly I have en- deavored with some elaboration to make it plain that this legal knowledge was not extraordinary, or such as to imply that the author was educated as a lawyer, or even as a lawyer's clerk. In ad- dition to dealing with this rather technical phase of the general subject, I have sought from the plays themselves and from other sources to bring together materials which have a bearing upon the question of authorship, and some of which, though familiar enough of themselves, have not been sufficiently considered in this special aspect. The writer of the plays showed an intimate M758108 iv PREFACE familiarity with many things which it is believed would have been known to Shakespeare but not to Bacon and I have to collect the most '; soughtO important of these, to exhibit them in some de- tail, and to arrange them in order, so that their weight may be easily understood and appreci- ated. -

English Professional Theatre, 1530-1660 Edited by Glynne Wickham, Herbert Berry and William Ingram Index More Information

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-10082-3 - English Professional Theatre, 1530-1660 Edited by Glynne Wickham, Herbert Berry and William Ingram Index More information Index Note: search under ‘London and Environs’; ‘Playing Companies’; ‘Playhouses’; and ‘Stage Characters’ for individual entries appropriate to those categories. Abell, William (alderman), 586 Andrews, Richard (player), 245 Abuses, 318 Anglin, Jay P., ‘The Schools of Defense’, Acton, Mr (justice of the peace), 158 296 Actors. See Players Anglo, Sydney, 20; ‘Court Festivals’, 291 Adams, John (player), 300 Annals of England. See Stow, John Adams, Joseph Quincy, Shakespearean Playhouse, Anne, Queen, 119, 122, 125, 513–14, 561, 562, 550n, 597n, 626n; Dramatic Records of Sir 564, 580, 625, 630–1; her company of Henry Herbert, 581, 582, 582n players, see Playing Companies Admiral, Lord. See Lord Admiral Apothecaries, 388, 501 Admiral’s players. See Playing Companies Arber, Edward, 192 Aesop, 171 Archer, George (rent gatherer), 611n Agrippa, Henry Cornelius (writer), 159 Arches, Court of the, 292, 294n, 312 Alabaster, William (playwright), 650 Ariosto, Ludovico, I Suppositi, 297n Aldermen of London. See London Armin, Robert (player and writer), 123, 196, Alderson, Thomas (sailor), 643 197, 198; Foole vpon Foole, 411–12 All Hallowtide, 100 Army Plot, The, 625, 636 All Saints Day, 35 Arthur, Thomas (apprentice player), 275–7 Allen, Giles, 330–2&n, 333–6&n, 340, 343–4, Arundel, Earl of (Henry Fitzalan, twelfth Earl), 346–7, 348, 352, 355, 356–7, 367–72, 372–5, 73, 308; his company -

“Revenge in Shakespeare's Plays”

“REVENGE IN SHAKESPEARE’S PLAYS” “OTHELLO” – LECTURE/CLASS WRITTEN: 1603-1604…. although some critics place the date somewhat earlier in 1601- 1602 mainly on the basis of some “echoes” of the play in the 1603 “bad” quarto of “Hamlet”. AGE: 39-40 Years Old (B.1564-D.1616) CHRONO: Four years after “Hamlet”; first in the consecutive series of tragedies followed by “King Lear”, “Macbeth” then “Antony and Cleopatra”. GENRE: “The Great Tragedies” SOURCES: An Italian tale in the collection “Gli Hecatommithi” (1565) of Giovanni Battista Giraldi (writing under the name Cinthio) from which Shakespeare also drew for the plot of “Measure for Measure”. John Pory’s 1600 translation of John Leo’s “A Geographical History of Africa”; Philemon Holland’s 1601 translation of Pliny’s “History of the World”; and Lewis Lewkenor’s 1599 “The Commonwealth and Government of Venice” mainly translated from a Latin text by Cardinal Contarini. STRUCTURE: “More a domestic tragedy than ‘Hamlet’, ‘Lear’ or ‘Macbeth’ concentrating on the destruction of Othello’s marriage and his murder of his wife rather than on affairs of state and the deaths of kings”. SUCCESS: The tragedy met with high success both at its initial Globe staging and well beyond mainly because of its exotic setting (Venice then Cypress), the “foregrounding of issues of race, gender and sexuality”, and the powerhouse performance of Richard Burbage, the most famous actor in Shakespeare’s company. HIGHLIGHT: Performed at the Banqueting House at Whitehall before King James I on 1 November 1604. AFTER: The play has been performed steadily since 1604; for a production in 1660 the actress Margaret Hughes as Desdemona “could have been the first professional actress on the English stage”.