The Elizabethan Age

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

English Renaissance

1 ENGLISH RENAISSANCE Unit Structure: 1.0 Objectives 1.1 The Historical Overview 1.2 The Elizabethan and Jacobean Ages 1.2.1 Political Peace and Stability 1.2.2 Social Development 1.2.3 Religious Tolerance 1.2.4 Sense and Feeling of Patriotism 1.2.5 Discovery, Exploration and Expansion 1.2.6 Influence of Foreign Fashions 1.2.7 Contradictions and Set of Oppositions 1.3 The Literary Tendencies of the Age 1.3.1 Foreign Influences 1.3.2 Influence of Reformation 1.3.3 Ardent Spirit of Adventure 1.3.4 Abundance of Output 1.4 Elizabethan Poetry 1.4.1 Love Poetry 1.4.2 Patriotic Poetry 1.4.3 Philosophical Poetry 1.4.4 Satirical Poetry 1.4.5 Poets of the Age 1.4.6 Songs and Lyrics in Elizabethan Poetry 1.4.7 Elizabethan Sonnets and Sonneteers 1.5 Elizabethan Prose 1.5.1 Prose in Early Renaissance 1.5.2 The Essay 1.5.3 Character Writers 1.5.4 Religious Prose 1.5.5 Prose Romances 2 1.6 Elizabethan Drama 1.6.1 The University Wits 1.6.2 Dramatic Activity of Shakespeare 1.6.3 Other Playwrights 1.7. Let‘s Sum up 1.8 Important Questions 1.0. OBJECTIVES This unit will make the students aware with: The historical and socio-political knowledge of Elizabethan and Jacobean Ages. Features of the ages. Literary tendencies, literary contributions to the different of genres like poetry, prose and drama. The important writers are introduced with their major works. With this knowledge the students will be able to locate the particular works in the tradition of literature, and again they will study the prescribed texts in the historical background. -

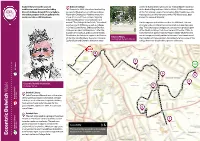

Eccentric Dulwich Walk Eccentric and Exit Via the Old College Gate

Explore Dulwich and its unusual 3 Dulwich College writer; Sir Edward George (known as “Steady Eddie”, Governor architecture and characters including Founded in 1619, the school was built by of the Bank of England from 1993 to 2003); C S Forester, writer Dulwich College, Dulwich Picture Gallery - successful Elizabethan actor Edward Alleyn. of the Hornblower novels; the comedian, Bob Monkhouse, who the oldest purpose-built art gallery in the Playwright Christopher Marlowe wrote him was expelled, and the humorous writer PG Wodehouse, best world, and Herne Hill Velodrome. some of his most famous roles. Originally known for Jeeves & Wooster. meant to educate 12 “poor scholars” and named “The College of God’s Gift,” the school On the opposite side of the road lies The Mill Pond. This was now has over 1,500 boys, as well as colleges originally a clay pit where the raw materials to make tiles were in China & South Korea. Old boys of Dulwich dug. The picturesque cottages you can see were probably part College are called “Old Alleynians”, after the of the tile kiln buildings that stood here until the late 1700s. In founder of the school, and include: Sir Ernest 1870 the French painter Camille Pissarro (1830-1903) fled the Shackleton, the Antarctic explorer; Ed Simons war in Europe and briefly settled in the area. Considered one of Edward Alleyn, of the Chemical Brothers; the actor, Chiwetel the founders of Impressionism, he painted a famous view of the photograph by Sara Moiola Ejiofor; Raymond Chandler, detective story college from here (now held in a private collection). -

The Edward Alleyn Golf Society, It Was for Me Immensely Enjoyable in My Own 49Th Year

T he Edward Alleyn G olf Society (Established 1968) Hon. Secretary: President: Dr Gary Savage MA PhD George Thorne Past Presidents: Sir Henry Cotton KCMG MBE 4 Bell Meadow Derek Fenner MA London Dr Colin Niven OBE SE19 1HP Dr Colin Diggory MA EdD [email protected] Tel: 0208 488 7828 The Society Christmas Dinner and Annual General Meeting will be held on Friday 8th December 2017 at Dulwich & Sydenham Hill GC, commencing with a drinks reception at 19:00. Present: Vince Abel, Steve Bargeron, Peter Battle, James Bridgeman, Tracy Bridgeman, Dave Britton, Roger Brunner, Andre Cutress, Roger Dollimore, Neil Hardwick, Perry Harley, Bob Joyce, John Knight, Dennis Lomas, Alan Miles, Roger Parkinson, Ted Pearce, Steve Poole, Jack Roberts, Keith Rodwell, John Smith, Ray Stiles, Justin Sutton, George Thorne, Tim Wareham, Alan Williams, Anton Williams; Guests: John Battle, Roy Croft, Neil French, Chris Nelson. Apologies: Mikael Berglund, Chris Briere-Edney, Trevor Cain, Dave Cleveland, Dom Cleveland, Len Cleveland, John Coleman, John Dunley, Dr Colin Diggory MA,EdD, John Etches, Ray Eyre, David Foulds, Mike Froggatt, Mark Gardner, David Hankin, Peter Holland, Bruce Leary, Dave McEvoy, Dave Sandars, Andrew Saunders, Paul Selwyn, Dave Slaney, Chris Shirtcliffe, Dr Gary Savage MA,PhD. In Memoriam A minute’s silence in memory of Society Members and other Alumni who have passed away this year : Kit Miller, attended 10 meetings between 1976 and 1991; Jim Calvo, attended 11 meetings and many tours between 2001 and 2015; Steve Crosby, attended 2 meetings in 1993-4; Brian Romilly non-golfer, but a great friend of many of our members. -

Newsletter #104 (Spring 1995)

The Dulwich Society - Newsletter 104 Spring - 1995 Contents What's on 1 Dulwich Park 13 Annual General Meeting 3 Wildlife 14 Obituary: Ronnie Reed 4 The Watchman Tree 16 Conservation Trust 7 Edward Alleyn Mystery 20 Transport 8 Letters 35 Chairman Joint Membership Secretaries Reg Collins Robin and Wilfrid Taylor 6 Eastlands Crescent, SE21 7EG 30 Walkerscroft Mead, SE21 81J Tel: 0181-693 1223 Tel: 0181-670 0890 Vice Chairman Editor W.P. Higman Brian McConnell 170 Burbage Road, SE21 7AG 9 Frank Dixon W1y, SE2 I 7ET Tel: 0171-274 6921 Tel & Fax: 0181-693 4423 Secretary Patrick Spencer Features Editor 7 Pond Cottages, Jane Furnival College Road, SE21 7LE 28 Little Bornes, SE21 SSE Tel: 0181-693 2043 Tel: 0181-670 6819 Treasurer Advertising Manager Russell Lloyd Anne-Maree Sheehan 138 Woodwarde Road, SE22 SUR 58 Cooper Close, SE! 7QU Tel: 0181-693 2452 Tel: 0171-928 4075 Registered under the Charities Act 1960 Reg. No. 234192 Registered with the Civic Trust Typesetting and Printing: Postal Publicity Press (S.J. Heady & Co. Ltd.) 0171-622 2411 1 DULWICH SOCIETY EVENTS NOTICE is hereby given that the 32nd Annual General Meeting of The 1995 Dulwich Society will be held at 8 p.m. on Friday March 10 1995 at St Faith's Friday, March 10. Annual General Meeting, St Faith's Centre, Red Post Hill, Community and Youth Centre, Red Post Hill, SE24 9JQ. 8p.m. Friday, March 24. Illustrated lecture, "Shrubs and herbaceous perennials for AGENDA the spring" by Aubrey Barker of Hopley's Nurseries. St Faith's Centre. -

SESSION DE JUIN 2018 / Du 4 Au 15 Juin 2018

SESSION DE JUIN 2018 / Du 4 au 15 juin 2018 EXAMEN : Civilisation B/EN .......................................... NUM. : BT0274 ........ TITULAIRE : Stuart Coe ................................................................................ ___________________________________________________________ There are TWO parts to this exam. Part One (40 marks) Answer one of the questions below. Please give examples and your opinion where appropriate. 1. How has invasion affected the history of Britain? 2. Was the Elizabethan era a golden age for England? 3. How does the education system in England differ from that of your own country? Do you think it is better? Why/Why not? 4. How does class affect the lives of British people? 5. What were the consequences for the British of winning the Second World War? 6. Who are the most important British prime ministers of the 20th century? Why? Part Two (20 marks) Put a tick or a cross next to the right answer. 1. Which Roman emperor conquered Britain? o Augustus o Nero o Caligula o Claudius 2. The Romans almost lost Britain as a province following an uprising led by: o Boudicca o Calgacus o Vercingetorix o Asterix 3. Who is the only English king to be given the title of 'the Great'? o Alfred o Canute o Egbert o Edward 4. Who instructed the waves to go back? o King Canute o King Henry V o Queen Victoria o King Alfred the Great 5. William the Conqueror defeated King Harold at the: o battle of Bosworth o battle of Marston Moor o battle of Crecy o battle of Hastings 6. In 1215 King John signed the Magna Carta, which stated that no free man could be: o tried by a jury o executed by the king o punished except through the law of the land o arrested by the sheriff of Nottingham if dressed as a chicken 7. -

"A Sharers' Repertory." Rethinking Theatrical

Syme, Holger Schott. "A Sharers’ Repertory." Rethinking Theatrical Documents in Shakespeare’s England. Ed. Tiffany Stern. London: The Arden Shakespeare, 2020. 33–51. Bloomsbury Collections. Web. 26 Sep. 2021. <http://dx.doi.org/10.5040/9781350051379.ch-002>. Downloaded from Bloomsbury Collections, www.bloomsburycollections.com, 26 September 2021, 08:28 UTC. Copyright © Tiffany Stern and contributors 2020. You may share this work for non-commercial purposes only, provided you give attribution to the copyright holder and the publisher, and provide a link to the Creative Commons licence. 2 A Sharers’ Repertory Holger Schott Syme Without Philip Henslowe, we would know next to nothing about the kinds of repertories early modern London’s resident theatre companies offered to their audiences. As things stand, thanks to the existence of the manuscript commonly known as Henslowe’s Diary , scholars have been able to contemplate the long lists of receipts and expenses that record the titles of well over 200 plays, most of them now lost. The Diary gives us some sense of the richness and diversity of this repertory, of the rapid turnover of plays, and of the kinds of investments theatre companies made to mount new shows. It also names a plethora of actors and other professionals associated with the troupes at the Rose. But, because the records are a fi nancier’s and theatre owner’s, not those of a sharer in an acting company, they do not document how a group of actors decided which plays to stage, how they chose to alternate successful shows, or what they, as actors, were looking for in new commissions. -

Galloping Onto the Throne: Queen Elizabeth I and the Symbolism of the Horse

Heidegger 1 Galloping onto the Throne: Queen Elizabeth I and the Symbolism of the Horse University of California, San Diego, Department of History, Undergraduate Honors Thesis By: Hannah von Heidegger Advisor: Ulrike Strasser, Ph.D. April 2019 Heidegger 2 Introduction As she prepared for the impending attack of the Spanish Armada, Queen Elizabeth I of England purportedly proclaimed proudly while on horseback to her troops, “I know I have the body but of a weak and feeble woman; but I have the heart and stomach of a king, and of a king of England too.”1 This line superbly captures the two identities that Elizabeth had to balance as a queen in the early modern period: the limitations imposed by her sex and her position as the leader of England. Viewed through the lens of stereotypical gender expectations in the early modern period, these two roles appear incompatible. Yet, Elizabeth I successfully managed the unique path of a female monarch with no male counterpart. Elizabeth was Queen of England from the 17th of November 1558, when her half-sister Queen Mary passed away, until her own death from sickness on March 24th, 1603, making her one of England’s longest reigning monarchs. She deliberately avoided several marriages, including high-profile unions with Philip II of Spain, King Eric of Sweden, and the Archduke Charles of Austria. Elizabeth’s position in her early years as ruler was uncertain due to several factors: a strong backlash to the rise of female rulers at the time; her cousin Mary Queen of Scots’ Catholic hereditary claim; and her being labeled a bastard by her father, Henry VIII. -

Lec-4 History of Social Welfare Developments in the UK

Topic 3 THE HISTORY OF AND DEVELOPMENT OF SOCIAL WELFARE IN THE UK: The history of social welfare in the UK had gone through various phases Before the Old Poor Law: ✓ During the early 1500s, the English government made little effort to address the needs of the poor. ✓ Rather, the poor were taken care of by Christians who were undertaking the seven-corporal works of mercy. ✓ These were deeds aimed to remove the worries and distress of those in need in accordance with their religious teachings. ▪ feed the hungry ▪ give drink to the thirsty ▪ welcome the stranger ▪ clothe the naked ▪ visit the sick ▪ visit the prisoner ▪ bury the dead ✓ The main formal organizations were the Church and the monasteries (a place reserved for prayer which may be a chapel, church or temple, or reserved for monks or nuns). The operation of charity made it possible for some poor people to survive if they left the land and came to the cities. ✓ However, when the Reformation1 happened, many people stopped following this Christian practice and the poor began to suffer greatly. ✓ The poverty and the begging were the ultimate problems followed by the Reformation. In 1531 Henry VI issued license for begging in restricted areas; punishment was given to those who violated the law. ✓ Poverty was one of the major problems Elizabeth faced during her rule. During this period the number of unemployed people grew considerably for a 1 The Reformation was a movement in Western Europe that aimed at reforming the doctrines and practices of the Roman Catholic Church The Monasteries had been dissolved by King Henry VIII in the years following 1536, this source of aid was no longer available to the poor. -

Schuler Dissertation Final Document

COUNSEL, POLITICAL RHETORIC, AND THE CHRONICLE HISTORY PLAY: REPRESENTING COUNCILIAR RULE, 1588-1603 DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Anne-Marie E. Schuler, B.M., M.A. Graduate Program in English The Ohio State University 2011 Dissertation Committee: Professor Richard Dutton, Advisor Professor Luke Wilson Professor Alan B. Farmer Professor Jennifer Higginbotham Copyright by Anne-Marie E. Schuler 2011 ABSTRACT This dissertation advances an account of how the genre of the chronicle history play enacts conciliar rule, by reflecting Renaissance models of counsel that predominated in Tudor political theory. As the texts of Renaissance political theorists and pamphleteers demonstrate, writers did not believe that kings and queens ruled by themselves, but that counsel was required to ensure that the monarch ruled virtuously and kept ties to the actual conditions of the people. Yet, within these writings, counsel was not a singular concept, and the work of historians such as John Guy, Patrick Collinson, and Ann McLaren shows that “counsel” referred to numerous paradigms and traditions. These theories of counsel were influenced by a variety of intellectual movements including humanist-classical formulations of monarchy, constitutionalism, and constructions of a “mixed monarchy” or a corporate body politic. Because the rhetoric of counsel was embedded in the language that men and women used to discuss politics, I argue that the plays perform a kind of cultural work, usually reserved for literature, that reflects, heightens, and critiques political life and the issues surrounding conceptions of conciliar rule. -

Sidney, Shakespeare, and the Elizabethans in Caroline England

Textual Ghosts: Sidney, Shakespeare, and the Elizabethans in Caroline England Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Rachel Ellen Clark, M.A. English Graduate Program The Ohio State University 2011 Dissertation Committee: Richard Dutton, Advisor Christopher Highley Alan Farmer Copyright by Rachel Ellen Clark 2011 Abstract This dissertation argues that during the reign of Charles I (1625-42), a powerful and long-lasting nationalist discourse emerged that embodied a conflicted nostalgia and located a primary source of English national identity in the Elizabethan era, rooted in the works of William Shakespeare, Sir Philip Sidney, John Lyly, and Ben Jonson. This Elizabethanism attempted to reconcile increasingly hostile conflicts between Catholics and Protestants, court and country, and elite and commoners. Remarkably, as I show by examining several Caroline texts in which Elizabethan ghosts appear, Caroline authors often resurrect long-dead Elizabethan figures to articulate not only Puritan views but also Arminian and Catholic ones. This tendency to complicate associations between the Elizabethan era and militant Protestantism also appears in Caroline plays by Thomas Heywood, Philip Massinger, and William Sampson that figure Queen Elizabeth as both ideally Protestant and dangerously ambiguous. Furthermore, Caroline Elizabethanism included reprintings and adaptations of Elizabethan literature that reshape the ideological significance of the Elizabethan era. The 1630s quarto editions of Shakespeare’s Elizabethan comedies The Merry Wives of Windsor, The Taming of the Shrew, and Love’s Labour’s Lost represent the Elizabethan era as the source of a native English wit that bridges social divides and negotiates the ii roles of powerful women (a renewed concern as Queen Henrietta Maria became more conspicuous at court). -

Shakespeare's Veiled Advocacy of Religious Tolerance in Twelfth Night

Shakespeare’s Veiled Advocacy of Religious Tolerance in Twelfth Night Maureen Richmond, MA Go directly to the text of the paper Abstract In Twelfth Night, William Shakespeare cleverly integrated references to pagan deities and beliefs, thus drawing attention to religious diversity extant in his day, an era otherwise steeped in orthodox Catholic and Protestant theologies. The discussion opens with a description of the historical, political, and religious backdrop against which Twelfth Night was composed. The long and largely peaceful reign of Elizabeth I was thought to be approaching an end. With this prospect came anxiety that the religious conflict which Elizabeth had so expertly contained might flare into widespread social disruption once again. In this fraught atmosphere, Shakespeare arrived with his adroit use of Elizabethan pun and word-play, cleverly scoring his points for cultural diversity while evading strict accountability. In this mode, Shakespeare in Twelfth Night made his characters invoke the Roman deities Mercury, Jove (or Jupiter), Vulcan, and Saturn, while also attributing destiny to the influence of the stars, the heavens, the gods, and fate – all notions which flew in the face of the conventional Christian theology dominant in Shakespeare’s day. Running a significant risk by putting such words in the mouths of his characters, Shakespeare alluded to a popular Elizabethan era astrological belief called the doctrine of correspondences and even poked fun at his characters using this specialized language he knew his audience would recognize. Shakespeare enthusiasts who’ve always wanted to better understand the inside humor of the bard will find their heart’s desires here, while also catching his drift about the need for a good-humored religious tolerance. -

Pembroke's Men in 1592–3, Their Repertory and Touring Schedule

Issues in Review 129 22 Leland H. Carlson, Martin Marprelate, Gentleman: Master Job Throckmorton Laid Open in his Colours (San Marino: Huntington Library, 1981), 72–81; Donald J. McGinn, John Penry and the Marprelate Controversy (New Bruns- wick, NJ, 1966), 134. 23 John Laurence, A History of Capital Punishment (New York, 1963), 9; see also Naish, Death Comes to the Maiden, 9, and Frances E. Dolan, ‘“Gentlemen, I have one more thing to say”: Women on Scaffolds in England, 1563–1680’, Modern Philology 92 (1994), 166. Pembroke’s Men in 1592–3, Their Repertory and Touring Schedule Some years ago, during a seminar on theatre history at the annual meeting of the Shakespeare Association of America, someone asked plaintively, ‘What did bad companies play in the provinces?’ and Leeds Barroll quipped, ‘Bad quartos’. The belief behind the joke – that ‘bad’ quartos and failing companies went together – has seemed specifically true of the earl of Pembroke’s players in 1592–3. Pembroke’s Men played in the provinces, and plays later published that advertised their ownership have been assigned to the category of texts known as ‘bad’ quartos. Even so, the company had reasons to be considered ‘good’. They enjoyed the patronage of Henry Herbert, the earl of Pembroke, and gave two of the five performances at court during Christmas, 1592–3 (26 December, 6 January). Their players, though probably young, were talented and committed to the profession: Richard Burbage, who would become a star with the Chamberlain’s/King’s Men, was still acting within a year of his death in 1619; William Sly acted with the Chamberlain’s/King’s Men until his death in 1608; Humphrey Jeffes acted with the Admiral’s/Prince’s/Palsgrave’s Men, 1597–1615; Robert Pallant and Robert Lee, who played with Worcester’s/ Queen Anne’s Men, were still active in the 1610s.