1 Introduction by Grace Ioppolo in 1619, the Celebrated Actor Edward

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Shakespeare's Elizabethan Public

University of Louisville ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository Electronic Theses and Dissertations 1-1925 Shakespeare's Elizabethan public. Joseph Anderson Burns University of Louisville Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.louisville.edu/etd Recommended Citation Burns, Joseph Anderson, "Shakespeare's Elizabethan public." (1925). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 182. https://doi.org/10.18297/etd/182 This Master's Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. This title appears here courtesy of the author, who has retained all other copyrights. For more information, please contact [email protected]. UNIVERSITY OF LOUISVILLE SHAKESPEARE'S ELIZABETHAN PUBLIC A Dissertation SUbm! tted to the Faculty Of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Department of English By Joseph Anderson Burns 1925. 7 Of all the arts drama is the most democratic. Other forms of artistic and aesthebic expression, literature, music, painting, may be cultivated in solitude. not so the drama. It is demanded by the public; produced for the public nd unless it is ~pproved by the public ito doom is certain. r/hy it; is that the drama can- not at any time break away from the .t.."as ...• es, prejudices, and ide 1 of the public for which it s written, M. Edelstand Du · eril has 1. -

Download Download

Early Theatre 9.2 Issues in Review Lucy Munro, Anne Lancashire, John Astington, and Marta Straznicky Popular Theatre and the Red Bull Governing the Pen to the Capacity of the Stage: Reading the Red Bull and Clerkenwell In his introduction to Early Theatre’s Issues in Review segment ‘Reading the Elizabethan Acting Companies’, published in 2001, Scott McMillin called for an approach to the study of early modern drama which takes theatre companies as ‘the organizing units of dramatic production’. Such an approach will, he suggests, entail reading plays ‘more fully than we have been trained to do, taking them not as authorial texts but as performed texts, seeing them as collaborative endeavours which involve the writers and dozens of other theatre people, and placing the staged plays in a social network to which both the players and audiences – perhaps even the playwrights – belonged’.1 We present here a variation on this approach: three essays that focus on the Red Bull theatre and its Clerkenwell locality. Rather than focusing on individual companies, we take the playhouse and location as our organising principle. Nonetheless, we are dealing with precisely the kind of decentring activity that McMillin had in mind, examining early drama through collaborative performance, through performance styles and audience taste, and through the presentation of a theatrical repertory in print. Each essay deals with a different ‘social network’: Anne Lancashire re-examines the evidence for the London Clerkenwell play, a multi-day biblical play performed by clerks in the late fourteenth and early fifteenth centuries; John Astington takes a look at acting traditions and repertory composition at the Red Bull and its fellow in the northern suburbs, Golden Lane’s Fortune playhouse; and Marta Straznicky looks at questions relating to the audience for Red Bull plays in the playhouse and the print-shop. -

1 Working with Lost Plays: “2 Fortune's Tennis” and the Admiral's Men

Working with lost plays: “2 Fortune’s Tennis” and the Admiral’s men David McInnis This chapter has a dual purpose: first, to revisit the most neglected of backstage plots (the plot commonly referred to as “2 Fortune’s Tennis”) and ask new questions about the information it provides; and second, to offer this inquiry as a case study of the methodology, aims and limitations of working with lost plays. “2 Fortune’s Tennis” has been dismissed by W. W. Greg and others as the “the most fragmentary of all the plots,” and for this reason remains the least studied of such documents.1 The title itself is a best-guess reconstruction: it appears in severely mutilated form (with substantial lacunae) as “The [plot of the sec]ond part of fortun[e’s tenn]is”.2 The precise date of the plot is uncertain (ca. 1597-1602), but scholars are confident in attributing it to the Admiral’s men, either at the Rose or the Fortune. On the rare occasion that this plot is discussed, scholarship focuses on questions of casting, on biographical information pertaining to the actors it names, and on the date and provenance of the document itself. The desire of some critics to associate the plot with an independently known play title like “Fortunatus” or “The Set at Tennis” has caused further confusion.3 Yet much of the clearest evidence that this plot contains— the names of characters in the play—has been ignored. This chapter focuses on the characters named in the plot, and asks questions concerning company commerce and repertorial strategy. -

3D Computer Modelling the Rose Playhouse Phase I (1587- 1591) and Phase II (1591-1606)

3D Computer Modelling The Rose Playhouse Phase I (1587- 1591) and Phase II (1591-1606) *** Research Document Compiled by Dr Roger Clegg Computer Model created by Dr Eric Tatham, Mixed Reality Ltd. 1 BLANK PAGE 2 Contents Acknowledgements…………………………………………………………………….………………….………………6-7 Foreword…………………………………………………………………………………………………………….9-10 1. Introduction……………………..………...……………………………………………………….............………....11-15 2. The plot of land 2.1 The plot………………………………………………..………………………….………….……….……..…17-19 2.2 Sewer and boundary ditches……………………………………………….……………….………….19-23 3. The Rose playhouse, Phase I (1587-1591) 3.1 Bridges and main entrance……………………..……………………………………,.……………….25-26 3.2 Exterior decoration 3.2.1 The sign of the Rose…………………………………………………………………………27-28 3.2.2 Timber frame…………………………………………………..………………………………28-31 3.3. Walls…………………………………………………………………………………………………………….32-33 3.3.1 Outer walls………………………………………………………….…………………………..34-36 3.3.2 Windows……………………………………………………………..…………...……………..37-38 3.3.3 Inner walls………………………………………………………………………………………39-40 3.4 Timber superstructure…………………………………………….……….…………….…….………..40-42 3.4.1 The Galleries………………………………………………..…………………….……………42-47 3.4.2 Jutties……………………………………………………………...….…………………………..48-50 3.5 The yard………………………………………………………………………………………….…………….50-51 3.5.1 Relative heights………………………………………………...……………...……………..51-57 3.5.2. Main entrance to the playhouse……………………………………………………….58-61 3.6. ‘Ingressus’, or entrance into the lower gallery…………………………..……….……………62-65 3.7 Stairways……………………………………………………………………………………………………....66-71 -

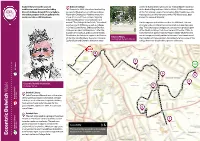

Eccentric Dulwich Walk Eccentric and Exit Via the Old College Gate

Explore Dulwich and its unusual 3 Dulwich College writer; Sir Edward George (known as “Steady Eddie”, Governor architecture and characters including Founded in 1619, the school was built by of the Bank of England from 1993 to 2003); C S Forester, writer Dulwich College, Dulwich Picture Gallery - successful Elizabethan actor Edward Alleyn. of the Hornblower novels; the comedian, Bob Monkhouse, who the oldest purpose-built art gallery in the Playwright Christopher Marlowe wrote him was expelled, and the humorous writer PG Wodehouse, best world, and Herne Hill Velodrome. some of his most famous roles. Originally known for Jeeves & Wooster. meant to educate 12 “poor scholars” and named “The College of God’s Gift,” the school On the opposite side of the road lies The Mill Pond. This was now has over 1,500 boys, as well as colleges originally a clay pit where the raw materials to make tiles were in China & South Korea. Old boys of Dulwich dug. The picturesque cottages you can see were probably part College are called “Old Alleynians”, after the of the tile kiln buildings that stood here until the late 1700s. In founder of the school, and include: Sir Ernest 1870 the French painter Camille Pissarro (1830-1903) fled the Shackleton, the Antarctic explorer; Ed Simons war in Europe and briefly settled in the area. Considered one of Edward Alleyn, of the Chemical Brothers; the actor, Chiwetel the founders of Impressionism, he painted a famous view of the photograph by Sara Moiola Ejiofor; Raymond Chandler, detective story college from here (now held in a private collection). -

Theater and Neighborhood in Shakespeare's

ENGLISH 8720: Theater and Neighborhood in Shakespeare’s London Spring Semester 2013 Professor Christopher Highley Classroom: Scott Lab N0044 Class time: Fri 11:10-2:05 Office: Denney 558; 292-1833 Office Hours: Wed 10-2 and by appointment [email protected] Class Description: This class will examine the different theatrical neighborhoods of Early Modern London in which the plays of Shakespeare and his contemporaries were performed. We will pay special attention to three neighborhoods: Southwark, on the south-bank of the River Thames, was home to the Globe, the Rose, and several other ampitheaters; Blackfriars, an ex-monastic Liberty inside the walls of the City, was home to indoor theaters; and Clerkenwell, northwest of the City, was the location of the Fortune and Red Bull playhouses. When and for what reasons was playing first attracted to these areas? What political, economic, demographic, and social conditions allowed playing to survive here? What local neighborhood pressures shaped the identity and fortunes of these venues? Did the location of a playhouse determine the composition of its audience and thus the kinds of plays performed? Did playwrights build awareness of the playhouse neighborhood into their plays? We will read representative plays from each of the theaters we study (for exxmple, Jonson's The Alchemist, and Beaumont’s Knight of the Burning Pestle for the Blackfriars), but we will also devote much of our attention to the social and theatrical documents that reveal how theaters functioned within specific neighborhoods. We will look at the documents of royal, metropolitan, and ecclesiastical authorities, along with petitions of neighborhood residents, contemporary accounts of playgoing, and anti-theatrical tracts. -

The Edward Alleyn Golf Society, It Was for Me Immensely Enjoyable in My Own 49Th Year

T he Edward Alleyn G olf Society (Established 1968) Hon. Secretary: President: Dr Gary Savage MA PhD George Thorne Past Presidents: Sir Henry Cotton KCMG MBE 4 Bell Meadow Derek Fenner MA London Dr Colin Niven OBE SE19 1HP Dr Colin Diggory MA EdD [email protected] Tel: 0208 488 7828 The Society Christmas Dinner and Annual General Meeting will be held on Friday 8th December 2017 at Dulwich & Sydenham Hill GC, commencing with a drinks reception at 19:00. Present: Vince Abel, Steve Bargeron, Peter Battle, James Bridgeman, Tracy Bridgeman, Dave Britton, Roger Brunner, Andre Cutress, Roger Dollimore, Neil Hardwick, Perry Harley, Bob Joyce, John Knight, Dennis Lomas, Alan Miles, Roger Parkinson, Ted Pearce, Steve Poole, Jack Roberts, Keith Rodwell, John Smith, Ray Stiles, Justin Sutton, George Thorne, Tim Wareham, Alan Williams, Anton Williams; Guests: John Battle, Roy Croft, Neil French, Chris Nelson. Apologies: Mikael Berglund, Chris Briere-Edney, Trevor Cain, Dave Cleveland, Dom Cleveland, Len Cleveland, John Coleman, John Dunley, Dr Colin Diggory MA,EdD, John Etches, Ray Eyre, David Foulds, Mike Froggatt, Mark Gardner, David Hankin, Peter Holland, Bruce Leary, Dave McEvoy, Dave Sandars, Andrew Saunders, Paul Selwyn, Dave Slaney, Chris Shirtcliffe, Dr Gary Savage MA,PhD. In Memoriam A minute’s silence in memory of Society Members and other Alumni who have passed away this year : Kit Miller, attended 10 meetings between 1976 and 1991; Jim Calvo, attended 11 meetings and many tours between 2001 and 2015; Steve Crosby, attended 2 meetings in 1993-4; Brian Romilly non-golfer, but a great friend of many of our members. -

From Sidney to Heywood: the Social Status of Commercial Theatre in Early Modern London

From Sidney to Heywood: the social status of commercial theatre in early modern London Romola Nuttall (King’s College London, UK) The Literary London Journal, Volume 14 Number 1 (Spring 2017) Abstract Thomas Heywood’s Apology for Actors (written c. 1608, published 1612) is one of the only stand-alone, printed deFences of the proFessional theatre to emerge from the early modern period. Even more significantly, it is ‘the only contemporary complete text we have – by an early modern actor about early modern actors’ (Griffith 191). This is rather surprising considering how famous playwrights and drama of that period have become, but it is revealing of attitudes towards the profession and the stage at the turn of the sixteenth century. Religious concerns Formed a central part of the heated public debate which contested the social value oF proFessional drama during the early modern era. Claims against the literary status of work produced for the commercial stage were also frequently levelled against the theatre from within the establishment, a prominent example being Sir Philip Sidney’s Defence of Poesie (written c. 1579, published 1595). Considering Heywood’s Apology in relation to Sidney’s Defence, and thinking particularly about the ways these treatises appropriate the classical idea oF mimesis and the consequent social value of literature, gives fresh insight into the changing status of drama in Shakespeare’s lifetime and how attitudes towards commercial theatre developed between the 1570s and 1610s. The following article explores these ideas within the framework of the London in which Heywood and his acting company lived and worked. -

A Noise Within Study Guide Shakespeare Supplement

A Noise Within Study Guide Shakespeare Supplement California’s Home for the Classics California’s Home for the Classics California’s Home for the Classics Table of Contents Dating Shakespeare’s Plays 3 Life in Shakespeare’s England 4 Elizabethan Theatre 8 Working in Elizabethan England 14 This Sceptered Isle 16 One Big Happy Family Tree 20 Sir John Falstaff and Tavern Culture 21 Battle of the Henries 24 Playing Nine Men’s Morris 30 FUNDING FOR A NOISE WITHIN’S EDUCATIONAL PROGRAMS IS PROVIDED IN paRT BY: The Ahmanson Foundation, Alliance for the Advancement of Arts Education, Supervisor Michael D. Antonovich, Employees Community Fund of Boeing California, The Capital Group Companies, Citigroup Foundation, Disney Worldwide Outreach, Doukas Family Foundation, Ellingsen Family Foundation, The Herb Alpert Foundation, The Green Foundation, Kiwanis Club of Glendale, Lockheed Federal Credit Union, Los Angeles County Arts Commission, B.C. McCabe Foundation, Metropolitan Associates, National Endowment for the Arts, The Kenneth T. and Eileen L. Norris Foundation, The Steinmetz Foundation, Dwight Stuart Youth Foundation, Waterman Foundation, Zeigler Family Foundation. 2 A Noise Within Study Guide Shakespeare Supplement Dating Shakespeare’s Plays Establishing an exact date for the Plays of Shakespeare. She theorized that authorship of Shakespeare’s plays is a very Shakespeare (a “stupid, ignorant, third- difficult task. It is impossible to pin down rate play actor”) could not have written the exact order, because there are no the plays attributed to him. The Victorians records giving details of the first production. were suspicious that a middle-class actor Many of the plays were performed years could ever be England’s greatest poet as before they were first published. -

Newsletter #104 (Spring 1995)

The Dulwich Society - Newsletter 104 Spring - 1995 Contents What's on 1 Dulwich Park 13 Annual General Meeting 3 Wildlife 14 Obituary: Ronnie Reed 4 The Watchman Tree 16 Conservation Trust 7 Edward Alleyn Mystery 20 Transport 8 Letters 35 Chairman Joint Membership Secretaries Reg Collins Robin and Wilfrid Taylor 6 Eastlands Crescent, SE21 7EG 30 Walkerscroft Mead, SE21 81J Tel: 0181-693 1223 Tel: 0181-670 0890 Vice Chairman Editor W.P. Higman Brian McConnell 170 Burbage Road, SE21 7AG 9 Frank Dixon W1y, SE2 I 7ET Tel: 0171-274 6921 Tel & Fax: 0181-693 4423 Secretary Patrick Spencer Features Editor 7 Pond Cottages, Jane Furnival College Road, SE21 7LE 28 Little Bornes, SE21 SSE Tel: 0181-693 2043 Tel: 0181-670 6819 Treasurer Advertising Manager Russell Lloyd Anne-Maree Sheehan 138 Woodwarde Road, SE22 SUR 58 Cooper Close, SE! 7QU Tel: 0181-693 2452 Tel: 0171-928 4075 Registered under the Charities Act 1960 Reg. No. 234192 Registered with the Civic Trust Typesetting and Printing: Postal Publicity Press (S.J. Heady & Co. Ltd.) 0171-622 2411 1 DULWICH SOCIETY EVENTS NOTICE is hereby given that the 32nd Annual General Meeting of The 1995 Dulwich Society will be held at 8 p.m. on Friday March 10 1995 at St Faith's Friday, March 10. Annual General Meeting, St Faith's Centre, Red Post Hill, Community and Youth Centre, Red Post Hill, SE24 9JQ. 8p.m. Friday, March 24. Illustrated lecture, "Shrubs and herbaceous perennials for AGENDA the spring" by Aubrey Barker of Hopley's Nurseries. St Faith's Centre. -

"A Sharers' Repertory." Rethinking Theatrical

Syme, Holger Schott. "A Sharers’ Repertory." Rethinking Theatrical Documents in Shakespeare’s England. Ed. Tiffany Stern. London: The Arden Shakespeare, 2020. 33–51. Bloomsbury Collections. Web. 26 Sep. 2021. <http://dx.doi.org/10.5040/9781350051379.ch-002>. Downloaded from Bloomsbury Collections, www.bloomsburycollections.com, 26 September 2021, 08:28 UTC. Copyright © Tiffany Stern and contributors 2020. You may share this work for non-commercial purposes only, provided you give attribution to the copyright holder and the publisher, and provide a link to the Creative Commons licence. 2 A Sharers’ Repertory Holger Schott Syme Without Philip Henslowe, we would know next to nothing about the kinds of repertories early modern London’s resident theatre companies offered to their audiences. As things stand, thanks to the existence of the manuscript commonly known as Henslowe’s Diary , scholars have been able to contemplate the long lists of receipts and expenses that record the titles of well over 200 plays, most of them now lost. The Diary gives us some sense of the richness and diversity of this repertory, of the rapid turnover of plays, and of the kinds of investments theatre companies made to mount new shows. It also names a plethora of actors and other professionals associated with the troupes at the Rose. But, because the records are a fi nancier’s and theatre owner’s, not those of a sharer in an acting company, they do not document how a group of actors decided which plays to stage, how they chose to alternate successful shows, or what they, as actors, were looking for in new commissions. -

Redating Pericles: a Re-Examination of Shakespeare’S

REDATING PERICLES: A RE-EXAMINATION OF SHAKESPEARE’S PERICLES AS AN ELIZABETHAN PLAY A THESIS IN Theatre Presented to the Faculty of the University of Missouri-Kansas City in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree MASTER OF ARTS by Michelle Elaine Stelting University of Missouri Kansas City December 2015 © 2015 MICHELLE ELAINE STELTING ALL RIGHTS RESERVED REDATING PERICLES: A RE-EXAMINATION OF SHAKESPEARE’S PERICLES AS AN ELIZABETHAN PLAY Michelle Elaine Stelting, Candidate for the Master of Arts Degree University of Missouri-Kansas City, 2015 ABSTRACT Pericles's apparent inferiority to Shakespeare’s mature works raises many questions for scholars. Was Shakespeare collaborating with an inferior playwright or playwrights? Did he allow so many corrupt printed versions of his works after 1604 out of indifference? Re-dating Pericles from the Jacobean to the Elizabethan era answers these questions and reveals previously unexamined connections between topical references in Pericles and events and personalities in the court of Elizabeth I: John Dee, Philip Sidney, Edward de Vere, and many others. The tournament impresas, alchemical symbolism of the story, and its lunar and astronomical imagery suggest Pericles was written long before 1608. Finally, Shakespeare’s focus on father-daughter relationships, and the importance of Marina, the daughter, as the heroine of the story, point to Pericles as written for a young girl. This thesis uses topical references, Shakespeare’s anachronisms, Shakespeare’s sources, stylometry and textual analysis, as well as Henslowe’s diary, the Stationers' Register, and other contemporary documentary evidence to determine whether there may have been versions of Pericles circulating before the accepted date of 1608.