John Heminges's Tap-House at the Globe the Theatre Profession Has A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

English Professional Theatre, 1530-1660 Edited by Glynne Wickham, Herbert Berry and William Ingram Index More Information

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-10082-3 - English Professional Theatre, 1530-1660 Edited by Glynne Wickham, Herbert Berry and William Ingram Index More information Index Note: search under ‘London and Environs’; ‘Playing Companies’; ‘Playhouses’; and ‘Stage Characters’ for individual entries appropriate to those categories. Abell, William (alderman), 586 Andrews, Richard (player), 245 Abuses, 318 Anglin, Jay P., ‘The Schools of Defense’, Acton, Mr (justice of the peace), 158 296 Actors. See Players Anglo, Sydney, 20; ‘Court Festivals’, 291 Adams, John (player), 300 Annals of England. See Stow, John Adams, Joseph Quincy, Shakespearean Playhouse, Anne, Queen, 119, 122, 125, 513–14, 561, 562, 550n, 597n, 626n; Dramatic Records of Sir 564, 580, 625, 630–1; her company of Henry Herbert, 581, 582, 582n players, see Playing Companies Admiral, Lord. See Lord Admiral Apothecaries, 388, 501 Admiral’s players. See Playing Companies Arber, Edward, 192 Aesop, 171 Archer, George (rent gatherer), 611n Agrippa, Henry Cornelius (writer), 159 Arches, Court of the, 292, 294n, 312 Alabaster, William (playwright), 650 Ariosto, Ludovico, I Suppositi, 297n Aldermen of London. See London Armin, Robert (player and writer), 123, 196, Alderson, Thomas (sailor), 643 197, 198; Foole vpon Foole, 411–12 All Hallowtide, 100 Army Plot, The, 625, 636 All Saints Day, 35 Arthur, Thomas (apprentice player), 275–7 Allen, Giles, 330–2&n, 333–6&n, 340, 343–4, Arundel, Earl of (Henry Fitzalan, twelfth Earl), 346–7, 348, 352, 355, 356–7, 367–72, 372–5, 73, 308; his company -

"A Sharers' Repertory." Rethinking Theatrical

Syme, Holger Schott. "A Sharers’ Repertory." Rethinking Theatrical Documents in Shakespeare’s England. Ed. Tiffany Stern. London: The Arden Shakespeare, 2020. 33–51. Bloomsbury Collections. Web. 26 Sep. 2021. <http://dx.doi.org/10.5040/9781350051379.ch-002>. Downloaded from Bloomsbury Collections, www.bloomsburycollections.com, 26 September 2021, 08:28 UTC. Copyright © Tiffany Stern and contributors 2020. You may share this work for non-commercial purposes only, provided you give attribution to the copyright holder and the publisher, and provide a link to the Creative Commons licence. 2 A Sharers’ Repertory Holger Schott Syme Without Philip Henslowe, we would know next to nothing about the kinds of repertories early modern London’s resident theatre companies offered to their audiences. As things stand, thanks to the existence of the manuscript commonly known as Henslowe’s Diary , scholars have been able to contemplate the long lists of receipts and expenses that record the titles of well over 200 plays, most of them now lost. The Diary gives us some sense of the richness and diversity of this repertory, of the rapid turnover of plays, and of the kinds of investments theatre companies made to mount new shows. It also names a plethora of actors and other professionals associated with the troupes at the Rose. But, because the records are a fi nancier’s and theatre owner’s, not those of a sharer in an acting company, they do not document how a group of actors decided which plays to stage, how they chose to alternate successful shows, or what they, as actors, were looking for in new commissions. -

The Dramatic Records of Sir Henry Herbert, Master of the Revels, 1623-1673

ill "iil! !!;i;i;i; K tftkrmiti THE LIBRARY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA LOS ANGELES Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2007 with funding from IVIicrosoft Corporation http://www.archive.org/details/dramaticrecordsoOOgreaiala CORNELL STUDIES IN ENGLISH EDITED BY JOSEPH QUINCY ADAMS LANE COOPER CLARK SUTHERLAND NORTHUP THE DRAMATIC RECORDS OF SIR HENRY HERBERT MASTER OF THE REVELS, 1623-1673 EDITED BY JOSEPH QUINCY ADAMS CORNELL UNIVERSITY NEW HAVEN: VALE UNIVERSITY PRESS LONDON: HUMPHREY MILKORD OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS MDCCCCXVII 7 7 Copyright, 191 By Yale University Press First published, October, 191 PRESS OF THE NEW ERA PRINTING COMPANY LANCASTER, PA. College Library TO CLARK SUTHERLAND NORTHUP AS A TOKEN OF ESTEEM 1092850 PREFACE The dramatic records of the Office of the Revels during the reigns of Edward VI, Mar>', and Elizabeth have been admirably edited with full indexes and notes by Professor Albert Feuillerat; but the records of the Office during the reigns of James I, Charles I, and Charles TI remain either unedited or scattered in mis- cellaneous volumes, none of which is indexed. Every scholar working in the field of the Tudor-Stuart drama must have felt the desirability of having these later records printed in a more accessible form. In the present volume I have attempted to bring together the dramatic records of Sir Henry Herbert, during whose long administration the Office of the Revels attained the height of its power and importance. These records, most of them preserved through Herbert's own care, consist of his office-book, covering the period of 1 622-1 642, a few documents relating to the same period, and miscellaneous documents relating to the management of the Office after the Restoration. -

Preservation and Innovation in the Intertheatrum Period, 1642-1660: the Survival of the London Theatre Community

Preservation and Innovation in the Intertheatrum Period, 1642-1660: The Survival of the London Theatre Community By Mary Alex Staude Honors Thesis Department of English and Comparative Literature University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill 2018 Approved: (Signature of Advisor) Acknowledgements I would like to thank Reid Barbour for his support, guidance, and advice throughout this process. Without his help, this project would not be what it is today. Thanks also to Laura Pates, Adam Maxfield, Alex LaGrand, Aubrey Snowden, Paul Smith, and Playmakers Repertory Company. Also to Diane Naylor at Chatsworth Settlement Trustees. Much love to friends and family for encouraging my excitement about this project. Particular thanks to Nell Ovitt for her gracious enthusiasm, and to Hannah Dent for her unyielding support. I am grateful for the community around me and for the communities that came before my time. Preface Mary Alex Staude worked on Twelfth Night 2017 with Alex LaGrand who worked on King Lear 2016 with Zack Powell who worked on Henry IV Part II 2015 with John Ahlin who worked on Macbeth 2000 with Jerry Hands who worked on Much Ado About Nothing 1984 with Derek Jacobi who worked on Othello 1964 with Laurence Olivier who worked on Romeo and Juliet 1935 with Edith Evans who worked on The Merry Wives of Windsor 1918 with Ellen Terry who worked on The Winter’s Tale 1856 with Charles Kean who worked on Richard III 1776 with David Garrick who worked on Hamlet 1747 with Charles Macklin who worked on Henry IV 1738 with Colley Cibber who worked on Julius Caesar 1707 with Thomas Betterton who worked on Hamlet 1661 with William Davenant who worked on Henry VIII 1637 with John Lowin who worked on Henry VIII 1613 with John Heminges who worked on Hamlet 1603 with William Shakespeare. -

The Beestons and the Art of Theatrical Management in Seventeenth-Century London

THE BEESTONS AND THE ART OF THEATRICAL MANAGEMENT IN SEVENTEENTH-CENTURY LONDON by Christopher M. Matusiak A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Department of English University of Toronto © Copyright by Christopher M. Matusiak (2009) Library and Archives Bibliothèque et Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de l’édition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre référence ISBN: 978-0-494-61029-9 Our file Notre référence ISBN: 978-0-494-61029-9 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non- L’auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library and permettant à la Bibliothèque et Archives Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par télécommunication ou par l’Internet, prêter, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des thèses partout dans le loan, distribute and sell theses monde, à des fins commerciales ou autres, sur worldwide, for commercial or non- support microforme, papier, électronique et/ou commercial purposes, in microform, autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L’auteur conserve la propriété du droit d’auteur ownership and moral rights in this et des droits moraux qui protège cette thèse. Ni thesis. Neither the thesis nor la thèse ni des extraits substantiels de celle-ci substantial extracts from it may be ne doivent être imprimés ou autrement printed or otherwise reproduced reproduits sans son autorisation. -

The Ignorant Elizabethan Author and Massinger's Believe As You List*

The Ignorant Elizabethan Author and Massinger's Believe as You List* My purpose is to explore the evidence of the management of the acting cast offered by one of the surviving manuscript plays of the Caroline theatre and to defend its author against the charge of theatrical ineptitude. The manuscript is that of Massinger's Believe as You List (MS Egerton 2,828) 1 prepared for performance in 1631. It is in Massinger's hand, but has been heavily annotated by a reviser whom I propose to call by his old theatrical title of Plotter. I am aware that this is to beg a question at the outset, for we really do not know how many functionaries were involved in the preparation of a seventeenth-century play or on what order they worked upon the' dramatist's script. Our common picture of the Elizabethan theatre is almost all built from inference, and despite the wealth of information we appear to possess in the play-texts, theatre Plots, manuscripts, and even the builders' contracts for the Fortune and Hope thea tres, almost every detail of our reconstructions of the playhouses and the methods of production and performance within them is the subject of scholarly dispute. The result is that we have no clear picture of the dramatist's craft as Shakespeare and his contemporaries practised it, or of the understood conditions that governed the production and perfor mance of their plays. That there were well-understood methods is apparent from the remarkable uniformity of the stage directions in printed texts and manuscripts throughout the whole period from the building of the Theatre in 1576 to the end of regular playing in 1642. -

Before the Beginning; After the End”: Stern, Tiffany

University of Birmingham “Before the Beginning; After the End”: Stern, Tiffany DOI: 10.1017/CBO9781139152259.023 License: Other (please provide link to licence statement Document Version Version created as part of publication process; publisher's layout; not normally made publicly available Citation for published version (Harvard): Stern, T 2015, “Before the Beginning; After the End”: When did Plays Start and Stop? in MJ Kidnie & S Massai (eds), Shakespeare and Textual Studies . Cambridge University Press, pp. 358-374. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781139152259.023 Link to publication on Research at Birmingham portal General rights Unless a licence is specified above, all rights (including copyright and moral rights) in this document are retained by the authors and/or the copyright holders. The express permission of the copyright holder must be obtained for any use of this material other than for purposes permitted by law. •Users may freely distribute the URL that is used to identify this publication. •Users may download and/or print one copy of the publication from the University of Birmingham research portal for the purpose of private study or non-commercial research. •User may use extracts from the document in line with the concept of ‘fair dealing’ under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 (?) •Users may not further distribute the material nor use it for the purposes of commercial gain. Where a licence is displayed above, please note the terms and conditions of the licence govern your use of this document. When citing, please reference the published version. Take down policy While the University of Birmingham exercises care and attention in making items available there are rare occasions when an item has been uploaded in error or has been deemed to be commercially or otherwise sensitive. -

Shakespeares First Folio: Four Centuries of an Iconic Book Pdf, Epub, Ebook

SHAKESPEARES FIRST FOLIO: FOUR CENTURIES OF AN ICONIC BOOK PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Emma Smith | 400 pages | 15 Jun 2016 | Oxford University Press | 9780198754367 | English | Oxford, United Kingdom Shakespeares First Folio: Four Centuries of an Iconic Book PDF Book Already have an account? The label Q n denotes the n th quarto edition of a play. The sheets were printed in 2-page formes, meaning that pages 1 and 12 of the first quire were printed simultaneously on one side of one sheet of paper which became the "outer" side ; then pages 2 and 11 were printed on the other side of the same sheet the "inner" side. Throughout, the stress is on what we can learn from individual copies now spread around the world about their eventful lives. Related Articles. It's hard to tell. A Shakespeare Companion — Stricter than, say, Bergen Evans or W3 "disinterested" means impartial — period , Strunk is in the last analysis whoops — "A bankrupt expression" a unique guide which means "without like or equal". Each copy has been part of many lives. And what did they do with them? Reader Writer Industry Professional. Korea national university of transportation. Jul 06, Michael P. Welcome back. It's a short but dense treatment of the topic and is focused on reading and readership, ownership, provenance, and what that says about how owners saw and treated the book. From the Book - First edition. Namespaces Article Talk. Loading Staff View. Glenn Crabtree rated it liked it Nov 25, The Foundations of Shakespeare's Text. Academic Skip to main content. The Passionate Pilgrim To the Queen. -

THE NATIONAL ARCHIVES LC 5/133, Pp. 44-51 1 ______

THE NATIONAL ARCHIVES LC 5/133, pp. 44-51 1 ________________________________________________________________________ SUMMARY The documents below are copies in the Lord Chamberlain’s Book of the petitions, answers and orders in a suit brought in 1635 before Philip Herbert (1584-1650), 1st Earl of Pembroke and Montgomery, whose first wife was Oxford’s daughter, Susan de Vere (1587-1629). At the time of the complaint, Herbert was Lord Chamberlain of the Household. See the Shakespeare Documented website at: https://shakespearedocumented.folger.edu/exhibition/document/answer-cuthbert-burbage- et-al-petition-robert-benefield-et-al-concerning The complaint is described from the perspective of one of the defendants, John Shank (d.1636). From the ODNB: Shank invested in the King's Men, holding shares that had originally belonged to John Heminges. On his death in 1630 the heir, Heminges's son William sold them to Shank. It was these shares and those of the surviving members of the Burbage family that were the subject of the dispute recorded in the Sharers' Papers of 1635. Robert Benfield, Eyllaerdt Swanston, and Thomas Pollard, fellow King's Men, petitioned the lord chamberlain to allow them to purchase shares in the Blackfriars and the Globe theatres. Richard Burbage's widow, Winifred, by then remarried, and her brother-in-law Cuthbert objected, as did John Shank. An order was made to allow the petitioners to buy some of Shank's shares, but no agreement was reached about the price. So on 1 August 1635 the case was passed to Sir Henry Herbert for arbitration. The matter had still not been finally resolved by Shank's death in January 1636. -

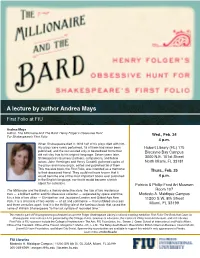

A Lecture by Author Andrea Mays First Folio at FIU

A lecture by author Andrea Mays First Folio at FIU Andrea Mays Author, The Millionaire And The Bard: Henry Folger’s Obsessive Hunt For Shakespeare’s First Folio Wed., Feb. 24 4 p.m. When Shakespeare died in 1616 half of his plays died with him. His plays were rarely performed, 18 of them had never been Hubert Library (HL) 175 published, and the rest existed only in bastardized forms that Biscayne Bay Campus did not stay true to his original language. Seven years later, Shakespeare’s business partners, companions, and fellow 3000 N.E. 151st Street actors, John Heminges and Henry Condell, gathered copies of North Miami, FL 33181 the plays and manuscripts, edited and published 36 of them. This massive book, the First Folio, was intended as a memorial to their deceased friend. They could not have known that it Thurs., Feb. 25 would become one of the most important books ever published 4 p.m. in the English language, nor that it would become a fetish object for collectors. Patricia & Phillip Frost Art Museum The Millionaire and the Bard is a literary detective story, the tale of two mysterious Room 107 men — a brilliant author and his obsessive collector — separated by space and time. Modesto A. Maidique Campus It is a tale of two cities — Elizabethan and Jacobean London and Gilded Age New 11200 S.W. 8th Street York. It is a chronicle of two worlds — of art and commerce — that unfolded an ocean and three centuries apart. And it is the thrilling tale of the luminous book that saved the Miami, FL 33199 name of William Shakespeare “to the last syllable of recorded time.” This event is part of FIU programming scheduled around the Folger Shakespeare Library’s national traveling exhibition First Folio! The Book that Gave Us Shakespeare. -

A Brief History of the Audience I Can Take Any Empty Space and Call It a Bare Stage

A Brief History of the Audience I can take any empty space and call it a bare stage. A man walks across this empty space whilst someone else is watching him, and this is all that is needed for an act of theatre to be engaged. —Peter Brook, The Empty Space The nature of the audience has changed throughout history, evolving from a participatory crowd to a group of people sitting behind an imaginary line, silently observing the performers. The audience is continually growing and changing. There has always been a need for human beings to communicate their wants, needs, perceptions and disagreements to others. This need to communicate is the foundation of art and the foundation of theatre’s relationship to its audience. In the Beginning ended with what the Christians called “morally Theatre began as ritual, with tribal dances and inappropriate” dancing mimes, violent spectator sports festivals celebrating the harvest, marriages, gods, war such as gladiator fights, and the public executions for and basically any other event that warranted a party. which the Romans were famous. The Romans loved People all over the world congregated in villages. It violence, and the audience was a lively crowd. was a participatory kind of theatre, the performers Because theatre was free, it was enjoyed by people of would be joined by the villagers who believed that every social class. They were vocal, enjoyed hissing their lives depended on a successful celebration—the bad actors off the stage, and loved to watch criminals harvest had to be plentiful or the battle victorious, or meet large ferocious animals, and soon after, enjoyed simply to be in good graces with their god or gods. -

William Shakespeare 1 William Shakespeare

William Shakespeare 1 William Shakespeare William Shakespeare The Chandos portrait, artist and authenticity unconfirmed. National Portrait Gallery, London. Born Baptised 26 April 1564 (birth date unknown) Stratford-upon-Avon, Warwickshire, England Died 23 April 1616 (aged 52) Stratford-upon-Avon, Warwickshire, England Occupation Playwright, poet, actor Nationality English Period English Renaissance Spouse(s) Anne Hathaway (m. 1582–1616) Children • Susanna Hall • Hamnet Shakespeare • Judith Quiney Relative(s) • John Shakespeare (father) • Mary Shakespeare (mother) Signature William Shakespeare (26 April 1564 (baptised) – 23 April 1616)[1] was an English poet and playwright, widely regarded as the greatest writer in the English language and the world's pre-eminent dramatist.[2] He is often called England's national poet and the "Bard of Avon".[3][4] His extant works, including some collaborations, consist of about 38 plays,[5] 154 sonnets, two long narrative poems, and a few other verses, the authorship of some of which is uncertain. His plays have been translated into every major living language and are performed more often than those of any other playwright.[6] Shakespeare was born and brought up in Stratford-upon-Avon. At the age of 18, he married Anne Hathaway, with whom he had three children: Susanna, and twins Hamnet and Judith. Between 1585 and 1592, he began a successful career in London as an actor, writer, and part-owner of a playing company called the Lord Chamberlain's Men, later known as the King's Men. He appears to have retired to Stratford around 1613 at age 49, where he died three years later.