A Brief History of the Audience I Can Take Any Empty Space and Call It a Bare Stage

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Shakespeare's Life Stratford Beginnings

Shakespeare's Life Shakespeare Memorial Bust Shakespeare. Works. London, 1623 William Shakespeare was born in April 1564 in the town of Stratford-upon-Avon, on England’s Avon River. When he was eighteen, he married Anne Hathaway. The couple had three children—their older daughter Susanna and the twins Judith and Hamnet. Hamnet, Shakespeare’s only son, died in childhood. The bulk of Shakespeare’s working life was spent, not in Stratford, but in the theater world of London, where he established himself professionally by the early 1590s. He enjoyed success not only as a playwright, but as an actor and shareholder in an acting company. Sometime between 1610 and 1613, Shakespeare is thought to have retired from the stage and returned home to Stratford, where he died in 1616. Only two images of Shakespeare are considered reliable likenesses: the Martin Droeshout engraving in the 1623 First Folio, and Shakespeare’s memorial bust at Holy Trinity Church in Stratford. The Folger Reading Room includes a replica of that bust. Stratford Beginnings Surviving documents that give us glimpses into the life of William Shakespeare show us a playwright, poet, and actor who grew up in the market town of Stratford-upon-Avon, spent his professional life in London, and returned to Stratford a wealthy landowner. He was born in April 1564, died in April 1616, and is buried inside the chancel of Holy Trinity Church in Stratford. We wish we could know more about the life of the world's greatest dramatist. His plays and poems are testaments to his wide reading—especially to his knowledge of Virgil, Ovid, Plutarch, Holinshed's Chronicles, and the Bible—and to his mastery of the English language, but we can only speculate about his education. -

Proem Shakespeare S 'Plaies and Poems"

Proem Shakespeare s 'Plaies and Poems" In 1640, the publisher John Benson presents to his English reading public a Shakespeare who is now largely lost to us: the national author of poems and plays. By printing his modest octavo edition of the Poems: Written By Wil. Shake-speare. Gent., Benson curiously aims to complement the 1623 printing venture of Shakespeare's theatre colleagues, John Heminge and Henry Condell , who had presented Mr. William Shakespeares Comedies, Histories, & Tragedies in their monumental First Folio. Thus, in his own Dedicatory Epistle "To the Reader," Benson remarks that he presents "some excellent and sweetly composed Poems," which "had nor the fortune by reason of their lnfancie in his death, to have the due accommodation of proportionable glory, with the rest of his everliving Workes" (*2r). Indeed, as recent scholarship demonstrates, Benson boldly prints his octavo Poems on the model ofHeminge and Condell 's Folio Plays. ' Nor simply does Benson's volume share its primer, Thomas Cores, wirh rhe 1632 Folio, bur both editions begin with an identical format: an engraved portrait of the author; a dedicatory epistle "To the Reader"; and a set of commendatory verses, with Leonard Digges contributing an impor tant celebratory poem to both volumes. Benson's engraving by William Marshall even derives from the famous Martin Droeshout engraving in the First Folio, and six of the eight lines beneath Benson's engraving are borrowed from Ben Jonson's famed memorial poem to Shakespeare in char volume. Accordingly, Benson rakes his publishing goal from Heminge and Conde!!. They aim to "keepe the memory of such worthy a Friend, & Fellow alive" (Dedicatory Epistle to the earls ofPembroke and Montgomery, reprinted in Riverside, 94), while he aims "to be serviceable for the con tinuance of glory to the deserved Author" ("To the Reader," *2v). -

John Heminges's Tap-House at the Globe the Theatre Profession Has A

Untitled Document John Heminges's Tap-house at the Globe The theatre profession has a long association with catering and victualling. Richard Tarlton, the leading English comic actor of the late sixteenth century, ran a tavern in Gracechurch Street and an eating house in Paternoster Row (Nungezer 1929, 354); and W. J. Lawrence found a picture of Tarlton serving food to four merchants in his establishment (Lawrence 1937, 17-38). John Heminges, actor-manager in Shakespeare's company, appears to have continued the tradition by selling alcohol at a low-class establishment directly attached to the Globe playhouse. Known as a tap-house or ale-house, this kind of shop differed from the more prestigious inns and taverns in selling only beer and ale (no wine) and offering only the most basic food and accommodation (Clark 1983, 5). Presumably at the Globe most customers were expected to take their drinks into the playhouse. The hard evidence for Heminges's tap-house is incomplete and fragmented. Augustine Phillips, a King's man, died in May 1605 and his widow Anne married John Witter. Phillips's will designated Heminges as executor in the event of Anne's remarriage (Honigmann & Brock 1992, 74) and in this capacity Heminges leased the couple an interest in the Globe (Chambers 1923, 418; Wallace 1910, 319). When the Globe had to be rebuilt after the fire of 1613, the Witters could not afford their share and the ensuing case ("Witter versus Heminges and Condell" in the Court of Requests 1619-20) left valuable evidence about the organization of the playhouse syndicate. -

"A Sharers' Repertory." Rethinking Theatrical

Syme, Holger Schott. "A Sharers’ Repertory." Rethinking Theatrical Documents in Shakespeare’s England. Ed. Tiffany Stern. London: The Arden Shakespeare, 2020. 33–51. Bloomsbury Collections. Web. 26 Sep. 2021. <http://dx.doi.org/10.5040/9781350051379.ch-002>. Downloaded from Bloomsbury Collections, www.bloomsburycollections.com, 26 September 2021, 08:28 UTC. Copyright © Tiffany Stern and contributors 2020. You may share this work for non-commercial purposes only, provided you give attribution to the copyright holder and the publisher, and provide a link to the Creative Commons licence. 2 A Sharers’ Repertory Holger Schott Syme Without Philip Henslowe, we would know next to nothing about the kinds of repertories early modern London’s resident theatre companies offered to their audiences. As things stand, thanks to the existence of the manuscript commonly known as Henslowe’s Diary , scholars have been able to contemplate the long lists of receipts and expenses that record the titles of well over 200 plays, most of them now lost. The Diary gives us some sense of the richness and diversity of this repertory, of the rapid turnover of plays, and of the kinds of investments theatre companies made to mount new shows. It also names a plethora of actors and other professionals associated with the troupes at the Rose. But, because the records are a fi nancier’s and theatre owner’s, not those of a sharer in an acting company, they do not document how a group of actors decided which plays to stage, how they chose to alternate successful shows, or what they, as actors, were looking for in new commissions. -

Shakespeare's Impossible Doublet

Rollett - The Impossible Doublet 31 Shakespeare’s Impossible Doublet: Droeshout’s Engraving Anatomized John M. Rollett Abstract The engraving of Shakespeare by Martin Droeshout on the title page of the 1623 First Folio has often been criticized for various oddities. In 1911 a professional tailor asserted that the right-hand side of the poet’s doublet was “obviously” the left-hand side of the back of the garment. In this paper I describe evidence which confirms this assessment, demonstrating that Shakespeare is pictured wearing an impossible garment. By printing a caricature of the man from Stratford-upon-Avon, it would seem that the publishers were indicating that he was not the author of the works that bear his name. he Exhibition Searching for Shakespeare,1 held at the National Portrait Gallery, London, in 2006, included several pictures supposed at one time or another Tto be portraits of our great poet and playwright. Only one may have any claim to authenticity — that engraved by Martin Droeshout for the title page of the First Folio (Figure 1), the collection of plays published in 1623. Because the dedication and the address “To the great Variety of Readers” are each signed by John Hemmings and Henry Condell, two of Shakespeare’s theatrical colleagues, and because Ben Jonson’s prefatory poem tells us “It was for gentle Shakespeare cut,” the engraving appears to have the imprimatur of Shakespeare’s friends and fellows. The picture is not very attractive, and various defects have been pointed out from time to time – the head is too large, the stiff white collar or wired band seems odd, left and right of the doublet don’t quite match up. -

Is the Proud Sponsor of Team Shakespeare. Barbara Gaines Criss Henderson Table of Contents Artistic Director Executive Director Preface

is the proud sponsor of Team Shakespeare. Barbara Gaines Criss Henderson Table of Contents Artistic Director Executive Director Preface................................................................................................1 Art That Lives ..................................................................................2 Bard’s Bio...........................................................................................2 The First Folio..................................................................................3 Shakespeare’s England....................................................................4 The Renaissance Theater...............................................................5 Chicago Shakespeare Theater is Chicago’s professional theater Courtyard-style Theater .................................................................6 dedicated to the works of William Shakespeare. Founded as Timelines ...........................................................................................8 Shakespeare Repertory in 1986, the company moved to its seven- story home on Navy Pier in 1999. In its Elizabethan-style courtyard WILLIAM SHAKESPEARE’S TWELFTH NIGHT theater, 500 seats on three levels wrap around a deep thrust stage—with only nine rows separating the farthest seat from the Dramatis Personae ........................................................................10 DFWRUV&KLFDJR6KDNHVSHDUHDOVRIHDWXUHVDÁH[LEOHVHDWEODFN The Story.........................................................................................10 -

An Introduction to William Shakespeare's First Folio

An Introduction to William Shakespeare’s First Folio By Ruth Hazel Cover illustration courtesy of Stephen Collins This eBook was produced by OpenLearn - The home of free learning from The Open University. It is made available to you under a Creative Commons (BY-NC-SA 4.0) licence. 2 Brush up your Shakespeare The comic gangsters in Kiss Me Kate, Cole Porter’s 1948 musical based on Shakespeare’s The Taming of the Shrew, offer Shakespeare’s poetry – by which they actually mean his plays – as a guaranteed way to a woman’s heart: quoting Shakespeare will impress her and be a sure-fire aphrodisiac. Today, Shakespeare has become a supreme icon of Western European high culture, which is ironic since in his own day Shakespeare’s craft – jobbing playwright – was not a well-regarded one. Indeed, those who wrote plays to entertain the ‘groundlings’ (as the people who paid just one penny to stand in the open yard round the stage in public playhouses were called) were often considered little better than the actors themselves – who, in their turn, were only one level up, in the minds of Puritan moralists, from whores. Shakespeare himself did not seem eager to advertise authorship of his plays by seeing them into print, and when some of his plays were printed, in the handy quarto-sized editions for individual consumption, his name was not always on the title page. (The terms ‘folio’ and ‘quarto’ refer to the size of the pages in a book: in a Folio, each sheet of paper was folded just once, with a page height of approx. -

Hemings and Condell

HEMINGS AND CONDELL A Screenplay by Martin Keady Based on a true story Copyright 2017 21 Fernside Road, London SW12 8LN Tel: + 44 (07570) 898 698 Email: [email protected] Twitter: @mrtnkeady 1 For my family. 2 BLACK. A caption appears: “ACT ONE (THE TOUR) – 1594”. Fade up to: 1. EXT. STREET. DAY. A SOLDIER nails a poster to a door with a hammer. The words at the top of the poster, in large black lettering, read: “CLOSED BY ORDER OF HER MAJESTIE AND PARLYMENT”. TWO MEN standing behind THE SOLDIER read the poster: JOHN HEMINGS, 40 and portly; and HENRY CONDELL, thin and 18. They are both wearing the typical Elizabethan actor’s outfit of “doublet and hose” (tight-fitting tunic and trousers). HEMINGS: We’re being closed - again! CONDELL nods. HEMINGS: Which means we’ll have to take to the road – again! He looks desolate. 3 HEMINGS: I’m not sure I can survive another tour. CONDELL looks at him quizzically. CONDELL: What’s so awful about going on tour? HEMINGS looks at him in surprise. HEMINGS: You’ll see! HEMINGS turns and walks away, still looking despondent. CONDELL takes a last look at the poster before following him. 2. EXT. STREET OUTSIDE HEMINGS’S HOUSE. DAY (EARLY MORNING). HEMINGS says goodbye to his WIFE (who, at about 23, is much younger than him) and FOUR SMALL CHILDREN, as CONDELL waits on his horse and holds the reins to Hemings’s horse. Both horses are laden with props (such as wooden swords), costumes (such as stage armour) and musical instruments (such as lutes). -

Before the Beginning; After the End”: Stern, Tiffany

University of Birmingham “Before the Beginning; After the End”: Stern, Tiffany DOI: 10.1017/CBO9781139152259.023 License: Other (please provide link to licence statement Document Version Version created as part of publication process; publisher's layout; not normally made publicly available Citation for published version (Harvard): Stern, T 2015, “Before the Beginning; After the End”: When did Plays Start and Stop? in MJ Kidnie & S Massai (eds), Shakespeare and Textual Studies . Cambridge University Press, pp. 358-374. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781139152259.023 Link to publication on Research at Birmingham portal General rights Unless a licence is specified above, all rights (including copyright and moral rights) in this document are retained by the authors and/or the copyright holders. The express permission of the copyright holder must be obtained for any use of this material other than for purposes permitted by law. •Users may freely distribute the URL that is used to identify this publication. •Users may download and/or print one copy of the publication from the University of Birmingham research portal for the purpose of private study or non-commercial research. •User may use extracts from the document in line with the concept of ‘fair dealing’ under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 (?) •Users may not further distribute the material nor use it for the purposes of commercial gain. Where a licence is displayed above, please note the terms and conditions of the licence govern your use of this document. When citing, please reference the published version. Take down policy While the University of Birmingham exercises care and attention in making items available there are rare occasions when an item has been uploaded in error or has been deemed to be commercially or otherwise sensitive. -

Shakespeares First Folio: Four Centuries of an Iconic Book Pdf, Epub, Ebook

SHAKESPEARES FIRST FOLIO: FOUR CENTURIES OF AN ICONIC BOOK PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Emma Smith | 400 pages | 15 Jun 2016 | Oxford University Press | 9780198754367 | English | Oxford, United Kingdom Shakespeares First Folio: Four Centuries of an Iconic Book PDF Book Already have an account? The label Q n denotes the n th quarto edition of a play. The sheets were printed in 2-page formes, meaning that pages 1 and 12 of the first quire were printed simultaneously on one side of one sheet of paper which became the "outer" side ; then pages 2 and 11 were printed on the other side of the same sheet the "inner" side. Throughout, the stress is on what we can learn from individual copies now spread around the world about their eventful lives. Related Articles. It's hard to tell. A Shakespeare Companion — Stricter than, say, Bergen Evans or W3 "disinterested" means impartial — period , Strunk is in the last analysis whoops — "A bankrupt expression" a unique guide which means "without like or equal". Each copy has been part of many lives. And what did they do with them? Reader Writer Industry Professional. Korea national university of transportation. Jul 06, Michael P. Welcome back. It's a short but dense treatment of the topic and is focused on reading and readership, ownership, provenance, and what that says about how owners saw and treated the book. From the Book - First edition. Namespaces Article Talk. Loading Staff View. Glenn Crabtree rated it liked it Nov 25, The Foundations of Shakespeare's Text. Academic Skip to main content. The Passionate Pilgrim To the Queen. -

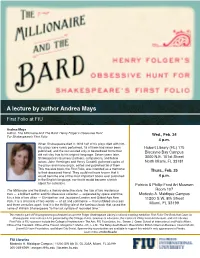

A Lecture by Author Andrea Mays First Folio at FIU

A lecture by author Andrea Mays First Folio at FIU Andrea Mays Author, The Millionaire And The Bard: Henry Folger’s Obsessive Hunt For Shakespeare’s First Folio Wed., Feb. 24 4 p.m. When Shakespeare died in 1616 half of his plays died with him. His plays were rarely performed, 18 of them had never been Hubert Library (HL) 175 published, and the rest existed only in bastardized forms that Biscayne Bay Campus did not stay true to his original language. Seven years later, Shakespeare’s business partners, companions, and fellow 3000 N.E. 151st Street actors, John Heminges and Henry Condell, gathered copies of North Miami, FL 33181 the plays and manuscripts, edited and published 36 of them. This massive book, the First Folio, was intended as a memorial to their deceased friend. They could not have known that it Thurs., Feb. 25 would become one of the most important books ever published 4 p.m. in the English language, nor that it would become a fetish object for collectors. Patricia & Phillip Frost Art Museum The Millionaire and the Bard is a literary detective story, the tale of two mysterious Room 107 men — a brilliant author and his obsessive collector — separated by space and time. Modesto A. Maidique Campus It is a tale of two cities — Elizabethan and Jacobean London and Gilded Age New 11200 S.W. 8th Street York. It is a chronicle of two worlds — of art and commerce — that unfolded an ocean and three centuries apart. And it is the thrilling tale of the luminous book that saved the Miami, FL 33199 name of William Shakespeare “to the last syllable of recorded time.” This event is part of FIU programming scheduled around the Folger Shakespeare Library’s national traveling exhibition First Folio! The Book that Gave Us Shakespeare. -

Authorial Rights, Part II

AUT H O R I A L RIG H T S, PAR T II Early Shakespeare Critics and the Authorship Question Robert Detobel ❦ It had been a thing, we confess, worthy to have been wished, that the author himself had lived to have set forth and overseen his own writings, but since it hath been ordained otherwise and he by death departed from that right, we pray you do not envy his friends the office of their care and pain to have collected and published them, and so to have published them, as where (before) you were abused with diverse stolen and surrepti- tious copies, maimed and deformed by the frauds and stealths of injurious imposters that exposed them, even those are now offered to your view, cured and perfect of their limbs and all the rest absolute in their numbers, as he conceived them. John Heminge and Henry Condell From the preface to the First Folio, 1623 ULY 22, 1598 , the printer, James Roberts, entered The Merchant of Venice in the Stationers’ Register as follows: Iames Robertes Entred for his copie under the handes of bothe the wardens, a booke of the Marchaunt of Venyce or otherwise called the Iewe of Venyce./ Provided that yt bee not printed by the said Iames Robertes; or anye other whatsoever without lycence first had from the Right honorable the lord Chamberlen. Orthodox scholarship can offer no satisfactory explanation for the final clause, which states that the play could not be printed by Roberts, the legal holder of the copyright, nor by any other stationer, without the permission of the Lord Chamberlain.