Before Shakespeare: the Drama of the 1580S Andy Kesson (University of Roehampton)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Climatic Variability in Sixteenth-Century Europe and Its Social Dimension: a Synthesis

CLIMATIC VARIABILITY IN SIXTEENTH-CENTURY EUROPE AND ITS SOCIAL DIMENSION: A SYNTHESIS CHRISTIAN PFISTER', RUDOLF BRAzDIL2 IInstitute afHistory, University a/Bern, Unitobler, CH-3000 Bern 9, Switzerland 2Department a/Geography, Masaryk University, Kotlar8M 2, CZ-61137 Bmo, Czech Republic Abstract. The introductory paper to this special issue of Climatic Change sununarizes the results of an array of studies dealing with the reconstruction of climatic trends and anomalies in sixteenth century Europe and their impact on the natural and the social world. Areas discussed include glacier expansion in the Alps, the frequency of natural hazards (floods in central and southem Europe and stonns on the Dutch North Sea coast), the impact of climate deterioration on grain prices and wine production, and finally, witch-hlllltS. The documentary data used for the reconstruction of seasonal and annual precipitation and temperatures in central Europe (Germany, Switzerland and the Czech Republic) include narrative sources, several types of proxy data and 32 weather diaries. Results were compared with long-tenn composite tree ring series and tested statistically by cross-correlating series of indices based OIl documentary data from the sixteenth century with those of simulated indices based on instrumental series (1901-1960). It was shown that series of indices can be taken as good substitutes for instrumental measurements. A corresponding set of weighted seasonal and annual series of temperature and precipitation indices for central Europe was computed from series of temperature and precipitation indices for Germany, Switzerland and the Czech Republic, the weights being in proportion to the area of each country. The series of central European indices were then used to assess temperature and precipitation anomalies for the 1901-1960 period using trmlsfer functions obtained from instrumental records. -

Robert Greene and the Theatrical Vocabulary of the Early 1590S Alan

Robert Greene and the Theatrical Vocabulary of the Early 1590s Alan C. Dessen [Writing Robert Greene: Essays on England’s First Notorious Professional Writer, ed. Kirk Melnikoff and Edward Gieskes (Aldershot and Burlington, VT: Ashgate, 2008), pp. 25-37.\ Here is a familiar tale found in literary handbooks for much of the twentieth century. Once upon a time in the 1560s and 1570s (the boyhoods of Marlowe, Shakespeare, and Jonson) English drama was in a deplorable state characterized by fourteener couplets, allegory, the heavy hand of didacticism, and touring troupes of players with limited numbers and resources. A first breakthrough came with the building of the first permanent playhouses in the London area in 1576- 77 (The Theatre, The Curtain)--hence an opportunity for stable groups to form so as to develop a repertory of plays and an audience. A decade later the University Wits came down to bring their learning and sophistication to the London desert, so that the heavyhandedness and primitive skills of early 1580s playwrights such as Robert Wilson and predecessors such as Thomas Lupton, George Wapull, and William Wager were superseded by the artistry of Marlowe, Kyd, and Greene. The introduction of blank verse and the suppression of allegory and onstage sermons yielded what Willard Thorp billed in 1928 as "the triumph of realism."1 Theatre and drama historians have picked away at some of these details (in particular, 1576 has lost some of its luster or uniqueness), but the narrative of the University Wits' resuscitation of a moribund English drama has retained its status as received truth. -

1580 Series Manual

Installation Guide Series 1580 Intercom Systems The Complete 1-on-2 Solution 2048 Mercer Road, Lexington, Kentucky 40511-1071 USA Phone: 859-233-4599 • Fax: 859-233-4510 Customer Toll-Free USA & Canada: 800-322-8346 www.audioauthority.com • [email protected] 2 Contents Introducing Series 1580 Intercom Systems 4 Series 1580 System Components 4 1580S and 1580HS Kits 4 Audio Installation 5 Lane Cable Information 6 Wiring 6 Advertising Messages 7 Traffic Sensors 8 Basic Calibration and Testing 9 Self Setup Mode 9 Troubleshooting Tips 9 Operation 10 Operator Guide 11 Using the 1550A Setup Tool 12 Advanced Calibration and Setup 12 Power User Tips 12 1550A Configuration Example 13 Definitions 14 Appendix 15 WARNINGS • Read these instructions before installing or using this product. • To reduce the risk of fire or electric shock, do not expose components to rain or moisture • This product must be installed by qualified personnel. • Do not expose this unit to excessive heat. • Clean the unit only with a dry or slightly dampened soft cloth. LIABILITY STATEMENT Every effort has been made to ensure that this product is free of defects. Audio Authority® cannot be held liable for the use of this hardware or any direct or indirect consequential damages arising from its use. It is the responsibility of the user of the hardware to check that it is suitable for his/her requirements and that it is installed correctly. All rights are reserved. No parts of this manual may be reproduced or transmitted by any form or means electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage or retrieval system without the written consent of the publisher. -

The Relationship of the Dramatic Works of John Lyly to Later Elizabethan Comedies

Durham E-Theses The relationship of the dramatic works of John Lyly to later Elizabethan comedies Gilbert, Christopher G. How to cite: Gilbert, Christopher G. (1965) The relationship of the dramatic works of John Lyly to later Elizabethan comedies, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/9816/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk 2 THE RELATIONSHIP OP THE DRAMATIC WORKS OP JOHN LYLY TO LATER ELIZABETHAN COMEDIES A Thesis Submitted in candidature for the degree of Master of Arts of the University of Durham by Christopher G. Gilbert 1965 The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. No quotation from it should be published without his prior written consent and information derived from it should be acknowledged. DECLARATION I declare this work is the result of my independent investigation. -

Poor Relief and the Church in Scotland, 1560−1650

George Mackay Brown and the Scottish Catholic Imagination Scottish Religious Cultures Historical Perspectives An innovative study of George Mackay Brown as a Scottish Catholic writer with a truly international reach This lively new study is the very first book to offer an absorbing history of the uncharted territory that is Scottish Catholic fiction. For Scottish Catholic writers of the twentieth century, faith was the key influence on both their artistic process and creative vision. By focusing on one of the best known of Scotland’s literary converts, George Mackay Brown, this book explores both the Scottish Catholic modernist movement of the twentieth century and the particularities of Brown’s writing which have been routinely overlooked by previous studies. The book provides sustained and illuminating close readings of key texts in Brown’s corpus and includes detailed comparisons between Brown’s writing and an established canon of Catholic writers, including Graham Greene, Muriel Spark and Flannery O’Connor. This timely book reveals that Brown’s Catholic imagination extended far beyond the ‘small green world’ of Orkney and ultimately embraced a universal human experience. Linden Bicket is a Teaching Fellow in the School of Divinity in New College, at the University of Edinburgh. She has published widely on George Mackay Brown Linden Bicket and her research focuses on patterns of faith and scepticism in the fictive worlds of story, film and theatre. Poor Relief and the Cover image: George Mackay Brown (left of crucifix) at the Italian Church in Scotland, Chapel, Orkney © Orkney Library & Archive Cover design: www.hayesdesign.co.uk 1560−1650 ISBN 978-1-4744-1165-3 edinburghuniversitypress.com John McCallum POOR RELIEF AND THE CHURCH IN SCOTLAND, 1560–1650 Scottish Religious Cultures Historical Perspectives Series Editors: Scott R. -

William Herle's Report of the Dutch Situation, 1573

LIVES AND LETTERS, VOL. 1, NO. 1, SPRING 2009 Signs of Intelligence: William Herle’s Report of the Dutch Situation, 1573 On the 11 June 1573 the agent William Herle sent his patron William Cecil, Lord Burghley a lengthy intelligence report of a ‘Discourse’ held with Prince William of Orange, Stadtholder of the Netherlands.∗ Running to fourteen folio manuscript pages, the Discourse records the substance of numerous conversations between Herle and Orange and details Orange’s efforts to persuade Queen Elizabeth to come to the aid of the Dutch against Spanish Habsburg imperial rule. The main thrust of the document exhorts Elizabeth to accept the sovereignty of the Low Countries in order to protect England’s naval interests and lead a league of protestant European rulers against Spain. This essay explores the circumstances surrounding the occasion of the Discourse and the context of the text within Herle’s larger corpus of correspondence. In the process, I will consider the methods by which the study of the material features of manuscripts can lead to a wider consideration of early modern political, secretarial and archival practices. THE CONTEXT By the spring of 1573 the insurrection in the Netherlands against Spanish rule was seven years old. Elizabeth had withdrawn her covert support for the English volunteers aiding the Dutch rebels, and was busy entertaining thoughts of marriage with Henri, Duc d’Alençon, brother to the King of France. Rejecting the idea of French assistance after the massacre of protestants on St Bartholomew’s day in Paris the previous year, William of Orange was considering approaching the protestant rulers of Europe, mostly German Lutheran sovereigns, to form a strong alliance against Spanish Catholic hegemony. -

Representations of Spain in Early Modern English Drama

Saugata Bhaduri Polycolonial Angst: Representations of Spain in Early Modern English Drama One of the important questions that this conference1 requires us to explore is how Spain was represented in early modern English theatre, and to examine such representation especially against the backdrop of the emergence of these two nations as arguably the most important players in the unfolding game of global imperialism. This is precisely what this article proposes to do: to take up representative English plays of the period belonging to the Anglo-Spanish War (1585–1604) which do mention Spain, analyse what the nature of their treat- ment of Spain is and hypothesise as to what may have been the reasons behind such a treatment.2 Given that England and Spain were at bitter war during these twenty years, and given furthermore that these two nations were the most prominent rivals in the global carving of the colonial pie that had already begun during this period, the commonsensical expectation from such plays, about the way Spain would be represented in them, should be of unambiguous Hispanophobia. There were several contextual reasons to occasion widespread Hispanophobia in the period. While Henry VIII’s marriage to Catherine of Aragon (1509) and its subsequent annulment (1533) had already sufficiently complicated Anglo-Hispanic relations, and their daughter Queen Mary I’s marriage to Philip II of Spain (1554) and his subsequent becoming the King of England and Ireland further aggravated the 1 The conference referred to here is the International Conference on Theatre Cultures within Globalizing Empires: Looking at Early Modern England and Spain, organised by the ERC Project “Early Modern European Drama and the Cultural Net (DramaNet),” at the Freie Universität, Ber- lin, November 15–16, 2012, where the preliminary version of this article was presented. -

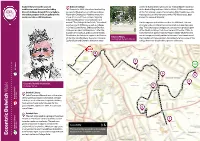

Eccentric Dulwich Walk Eccentric and Exit Via the Old College Gate

Explore Dulwich and its unusual 3 Dulwich College writer; Sir Edward George (known as “Steady Eddie”, Governor architecture and characters including Founded in 1619, the school was built by of the Bank of England from 1993 to 2003); C S Forester, writer Dulwich College, Dulwich Picture Gallery - successful Elizabethan actor Edward Alleyn. of the Hornblower novels; the comedian, Bob Monkhouse, who the oldest purpose-built art gallery in the Playwright Christopher Marlowe wrote him was expelled, and the humorous writer PG Wodehouse, best world, and Herne Hill Velodrome. some of his most famous roles. Originally known for Jeeves & Wooster. meant to educate 12 “poor scholars” and named “The College of God’s Gift,” the school On the opposite side of the road lies The Mill Pond. This was now has over 1,500 boys, as well as colleges originally a clay pit where the raw materials to make tiles were in China & South Korea. Old boys of Dulwich dug. The picturesque cottages you can see were probably part College are called “Old Alleynians”, after the of the tile kiln buildings that stood here until the late 1700s. In founder of the school, and include: Sir Ernest 1870 the French painter Camille Pissarro (1830-1903) fled the Shackleton, the Antarctic explorer; Ed Simons war in Europe and briefly settled in the area. Considered one of Edward Alleyn, of the Chemical Brothers; the actor, Chiwetel the founders of Impressionism, he painted a famous view of the photograph by Sara Moiola Ejiofor; Raymond Chandler, detective story college from here (now held in a private collection). -

The Edward Alleyn Golf Society, It Was for Me Immensely Enjoyable in My Own 49Th Year

T he Edward Alleyn G olf Society (Established 1968) Hon. Secretary: President: Dr Gary Savage MA PhD George Thorne Past Presidents: Sir Henry Cotton KCMG MBE 4 Bell Meadow Derek Fenner MA London Dr Colin Niven OBE SE19 1HP Dr Colin Diggory MA EdD [email protected] Tel: 0208 488 7828 The Society Christmas Dinner and Annual General Meeting will be held on Friday 8th December 2017 at Dulwich & Sydenham Hill GC, commencing with a drinks reception at 19:00. Present: Vince Abel, Steve Bargeron, Peter Battle, James Bridgeman, Tracy Bridgeman, Dave Britton, Roger Brunner, Andre Cutress, Roger Dollimore, Neil Hardwick, Perry Harley, Bob Joyce, John Knight, Dennis Lomas, Alan Miles, Roger Parkinson, Ted Pearce, Steve Poole, Jack Roberts, Keith Rodwell, John Smith, Ray Stiles, Justin Sutton, George Thorne, Tim Wareham, Alan Williams, Anton Williams; Guests: John Battle, Roy Croft, Neil French, Chris Nelson. Apologies: Mikael Berglund, Chris Briere-Edney, Trevor Cain, Dave Cleveland, Dom Cleveland, Len Cleveland, John Coleman, John Dunley, Dr Colin Diggory MA,EdD, John Etches, Ray Eyre, David Foulds, Mike Froggatt, Mark Gardner, David Hankin, Peter Holland, Bruce Leary, Dave McEvoy, Dave Sandars, Andrew Saunders, Paul Selwyn, Dave Slaney, Chris Shirtcliffe, Dr Gary Savage MA,PhD. In Memoriam A minute’s silence in memory of Society Members and other Alumni who have passed away this year : Kit Miller, attended 10 meetings between 1976 and 1991; Jim Calvo, attended 11 meetings and many tours between 2001 and 2015; Steve Crosby, attended 2 meetings in 1993-4; Brian Romilly non-golfer, but a great friend of many of our members. -

From Sidney to Heywood: the Social Status of Commercial Theatre in Early Modern London

From Sidney to Heywood: the social status of commercial theatre in early modern London Romola Nuttall (King’s College London, UK) The Literary London Journal, Volume 14 Number 1 (Spring 2017) Abstract Thomas Heywood’s Apology for Actors (written c. 1608, published 1612) is one of the only stand-alone, printed deFences of the proFessional theatre to emerge from the early modern period. Even more significantly, it is ‘the only contemporary complete text we have – by an early modern actor about early modern actors’ (Griffith 191). This is rather surprising considering how famous playwrights and drama of that period have become, but it is revealing of attitudes towards the profession and the stage at the turn of the sixteenth century. Religious concerns Formed a central part of the heated public debate which contested the social value oF proFessional drama during the early modern era. Claims against the literary status of work produced for the commercial stage were also frequently levelled against the theatre from within the establishment, a prominent example being Sir Philip Sidney’s Defence of Poesie (written c. 1579, published 1595). Considering Heywood’s Apology in relation to Sidney’s Defence, and thinking particularly about the ways these treatises appropriate the classical idea oF mimesis and the consequent social value of literature, gives fresh insight into the changing status of drama in Shakespeare’s lifetime and how attitudes towards commercial theatre developed between the 1570s and 1610s. The following article explores these ideas within the framework of the London in which Heywood and his acting company lived and worked. -

A Noise Within Study Guide Shakespeare Supplement

A Noise Within Study Guide Shakespeare Supplement California’s Home for the Classics California’s Home for the Classics California’s Home for the Classics Table of Contents Dating Shakespeare’s Plays 3 Life in Shakespeare’s England 4 Elizabethan Theatre 8 Working in Elizabethan England 14 This Sceptered Isle 16 One Big Happy Family Tree 20 Sir John Falstaff and Tavern Culture 21 Battle of the Henries 24 Playing Nine Men’s Morris 30 FUNDING FOR A NOISE WITHIN’S EDUCATIONAL PROGRAMS IS PROVIDED IN paRT BY: The Ahmanson Foundation, Alliance for the Advancement of Arts Education, Supervisor Michael D. Antonovich, Employees Community Fund of Boeing California, The Capital Group Companies, Citigroup Foundation, Disney Worldwide Outreach, Doukas Family Foundation, Ellingsen Family Foundation, The Herb Alpert Foundation, The Green Foundation, Kiwanis Club of Glendale, Lockheed Federal Credit Union, Los Angeles County Arts Commission, B.C. McCabe Foundation, Metropolitan Associates, National Endowment for the Arts, The Kenneth T. and Eileen L. Norris Foundation, The Steinmetz Foundation, Dwight Stuart Youth Foundation, Waterman Foundation, Zeigler Family Foundation. 2 A Noise Within Study Guide Shakespeare Supplement Dating Shakespeare’s Plays Establishing an exact date for the Plays of Shakespeare. She theorized that authorship of Shakespeare’s plays is a very Shakespeare (a “stupid, ignorant, third- difficult task. It is impossible to pin down rate play actor”) could not have written the exact order, because there are no the plays attributed to him. The Victorians records giving details of the first production. were suspicious that a middle-class actor Many of the plays were performed years could ever be England’s greatest poet as before they were first published. -

The First Three Commandments in the Polish Catholic Catechisms of the 1560S–1570S

CHAPTER 11 Man and God: The First Three Commandments in the Polish Catholic Catechisms of the 1560s–1570s Waldemar Kowalski Catechism: A New Tool in Religious Instruction The sixteenth century brought a number of fundamental and far-reaching changes in the Polish Church’s approach to the cura animarum (cure of souls). In practice, the laity previously had cursory access to the fundamentals of the faith. From the end of the Middle Ages up until the mid-seventeenth century, elementary catechesis was limited to the repetition of the Pater noster, Credo, Ave Maria and the Decalogue before the Sunday Mass. An average priest was able to mobilize his parishioners to repeat the Ten Commandments and to memorize the relevant verses, following synodical recommendations. It was a far more difficult task, however, to explain convincingly the moral obligations arising from them. Hypothetically these rudiments of faith were taught more effectively during the second half of the sixteenth century.1 One of the expla- nations for these changes was the relative growth in the ranks of the educated laity. This was also at least partly due to the proliferation of printed catechisms. They were composed and published with a view to explaining and promot- ing the principles of the faith in opposition to Lutheran and, later, Reformed attempts to evangelize the population. The fight against ‘heresy’, the reason for which the provincial synod in Piotrków convened in 1525, was thereafter to become part of a wider reform programme within the Church.2 Such a 1 For a thorough discussion of the possibilities and limitations of religious education at the turn of the modern age, see: Bylina S., Religijność późnego średniowiecza (Warsaw: 2009) 26–38.