A Possible Extension of Henslowe's and Alleyn's Sussex Network?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

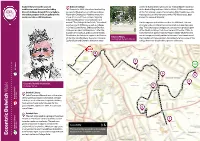

Eccentric Dulwich Walk Eccentric and Exit Via the Old College Gate

Explore Dulwich and its unusual 3 Dulwich College writer; Sir Edward George (known as “Steady Eddie”, Governor architecture and characters including Founded in 1619, the school was built by of the Bank of England from 1993 to 2003); C S Forester, writer Dulwich College, Dulwich Picture Gallery - successful Elizabethan actor Edward Alleyn. of the Hornblower novels; the comedian, Bob Monkhouse, who the oldest purpose-built art gallery in the Playwright Christopher Marlowe wrote him was expelled, and the humorous writer PG Wodehouse, best world, and Herne Hill Velodrome. some of his most famous roles. Originally known for Jeeves & Wooster. meant to educate 12 “poor scholars” and named “The College of God’s Gift,” the school On the opposite side of the road lies The Mill Pond. This was now has over 1,500 boys, as well as colleges originally a clay pit where the raw materials to make tiles were in China & South Korea. Old boys of Dulwich dug. The picturesque cottages you can see were probably part College are called “Old Alleynians”, after the of the tile kiln buildings that stood here until the late 1700s. In founder of the school, and include: Sir Ernest 1870 the French painter Camille Pissarro (1830-1903) fled the Shackleton, the Antarctic explorer; Ed Simons war in Europe and briefly settled in the area. Considered one of Edward Alleyn, of the Chemical Brothers; the actor, Chiwetel the founders of Impressionism, he painted a famous view of the photograph by Sara Moiola Ejiofor; Raymond Chandler, detective story college from here (now held in a private collection). -

The Edward Alleyn Golf Society, It Was for Me Immensely Enjoyable in My Own 49Th Year

T he Edward Alleyn G olf Society (Established 1968) Hon. Secretary: President: Dr Gary Savage MA PhD George Thorne Past Presidents: Sir Henry Cotton KCMG MBE 4 Bell Meadow Derek Fenner MA London Dr Colin Niven OBE SE19 1HP Dr Colin Diggory MA EdD [email protected] Tel: 0208 488 7828 The Society Christmas Dinner and Annual General Meeting will be held on Friday 8th December 2017 at Dulwich & Sydenham Hill GC, commencing with a drinks reception at 19:00. Present: Vince Abel, Steve Bargeron, Peter Battle, James Bridgeman, Tracy Bridgeman, Dave Britton, Roger Brunner, Andre Cutress, Roger Dollimore, Neil Hardwick, Perry Harley, Bob Joyce, John Knight, Dennis Lomas, Alan Miles, Roger Parkinson, Ted Pearce, Steve Poole, Jack Roberts, Keith Rodwell, John Smith, Ray Stiles, Justin Sutton, George Thorne, Tim Wareham, Alan Williams, Anton Williams; Guests: John Battle, Roy Croft, Neil French, Chris Nelson. Apologies: Mikael Berglund, Chris Briere-Edney, Trevor Cain, Dave Cleveland, Dom Cleveland, Len Cleveland, John Coleman, John Dunley, Dr Colin Diggory MA,EdD, John Etches, Ray Eyre, David Foulds, Mike Froggatt, Mark Gardner, David Hankin, Peter Holland, Bruce Leary, Dave McEvoy, Dave Sandars, Andrew Saunders, Paul Selwyn, Dave Slaney, Chris Shirtcliffe, Dr Gary Savage MA,PhD. In Memoriam A minute’s silence in memory of Society Members and other Alumni who have passed away this year : Kit Miller, attended 10 meetings between 1976 and 1991; Jim Calvo, attended 11 meetings and many tours between 2001 and 2015; Steve Crosby, attended 2 meetings in 1993-4; Brian Romilly non-golfer, but a great friend of many of our members. -

From Sidney to Heywood: the Social Status of Commercial Theatre in Early Modern London

From Sidney to Heywood: the social status of commercial theatre in early modern London Romola Nuttall (King’s College London, UK) The Literary London Journal, Volume 14 Number 1 (Spring 2017) Abstract Thomas Heywood’s Apology for Actors (written c. 1608, published 1612) is one of the only stand-alone, printed deFences of the proFessional theatre to emerge from the early modern period. Even more significantly, it is ‘the only contemporary complete text we have – by an early modern actor about early modern actors’ (Griffith 191). This is rather surprising considering how famous playwrights and drama of that period have become, but it is revealing of attitudes towards the profession and the stage at the turn of the sixteenth century. Religious concerns Formed a central part of the heated public debate which contested the social value oF proFessional drama during the early modern era. Claims against the literary status of work produced for the commercial stage were also frequently levelled against the theatre from within the establishment, a prominent example being Sir Philip Sidney’s Defence of Poesie (written c. 1579, published 1595). Considering Heywood’s Apology in relation to Sidney’s Defence, and thinking particularly about the ways these treatises appropriate the classical idea oF mimesis and the consequent social value of literature, gives fresh insight into the changing status of drama in Shakespeare’s lifetime and how attitudes towards commercial theatre developed between the 1570s and 1610s. The following article explores these ideas within the framework of the London in which Heywood and his acting company lived and worked. -

A Noise Within Study Guide Shakespeare Supplement

A Noise Within Study Guide Shakespeare Supplement California’s Home for the Classics California’s Home for the Classics California’s Home for the Classics Table of Contents Dating Shakespeare’s Plays 3 Life in Shakespeare’s England 4 Elizabethan Theatre 8 Working in Elizabethan England 14 This Sceptered Isle 16 One Big Happy Family Tree 20 Sir John Falstaff and Tavern Culture 21 Battle of the Henries 24 Playing Nine Men’s Morris 30 FUNDING FOR A NOISE WITHIN’S EDUCATIONAL PROGRAMS IS PROVIDED IN paRT BY: The Ahmanson Foundation, Alliance for the Advancement of Arts Education, Supervisor Michael D. Antonovich, Employees Community Fund of Boeing California, The Capital Group Companies, Citigroup Foundation, Disney Worldwide Outreach, Doukas Family Foundation, Ellingsen Family Foundation, The Herb Alpert Foundation, The Green Foundation, Kiwanis Club of Glendale, Lockheed Federal Credit Union, Los Angeles County Arts Commission, B.C. McCabe Foundation, Metropolitan Associates, National Endowment for the Arts, The Kenneth T. and Eileen L. Norris Foundation, The Steinmetz Foundation, Dwight Stuart Youth Foundation, Waterman Foundation, Zeigler Family Foundation. 2 A Noise Within Study Guide Shakespeare Supplement Dating Shakespeare’s Plays Establishing an exact date for the Plays of Shakespeare. She theorized that authorship of Shakespeare’s plays is a very Shakespeare (a “stupid, ignorant, third- difficult task. It is impossible to pin down rate play actor”) could not have written the exact order, because there are no the plays attributed to him. The Victorians records giving details of the first production. were suspicious that a middle-class actor Many of the plays were performed years could ever be England’s greatest poet as before they were first published. -

Newsletter #104 (Spring 1995)

The Dulwich Society - Newsletter 104 Spring - 1995 Contents What's on 1 Dulwich Park 13 Annual General Meeting 3 Wildlife 14 Obituary: Ronnie Reed 4 The Watchman Tree 16 Conservation Trust 7 Edward Alleyn Mystery 20 Transport 8 Letters 35 Chairman Joint Membership Secretaries Reg Collins Robin and Wilfrid Taylor 6 Eastlands Crescent, SE21 7EG 30 Walkerscroft Mead, SE21 81J Tel: 0181-693 1223 Tel: 0181-670 0890 Vice Chairman Editor W.P. Higman Brian McConnell 170 Burbage Road, SE21 7AG 9 Frank Dixon W1y, SE2 I 7ET Tel: 0171-274 6921 Tel & Fax: 0181-693 4423 Secretary Patrick Spencer Features Editor 7 Pond Cottages, Jane Furnival College Road, SE21 7LE 28 Little Bornes, SE21 SSE Tel: 0181-693 2043 Tel: 0181-670 6819 Treasurer Advertising Manager Russell Lloyd Anne-Maree Sheehan 138 Woodwarde Road, SE22 SUR 58 Cooper Close, SE! 7QU Tel: 0181-693 2452 Tel: 0171-928 4075 Registered under the Charities Act 1960 Reg. No. 234192 Registered with the Civic Trust Typesetting and Printing: Postal Publicity Press (S.J. Heady & Co. Ltd.) 0171-622 2411 1 DULWICH SOCIETY EVENTS NOTICE is hereby given that the 32nd Annual General Meeting of The 1995 Dulwich Society will be held at 8 p.m. on Friday March 10 1995 at St Faith's Friday, March 10. Annual General Meeting, St Faith's Centre, Red Post Hill, Community and Youth Centre, Red Post Hill, SE24 9JQ. 8p.m. Friday, March 24. Illustrated lecture, "Shrubs and herbaceous perennials for AGENDA the spring" by Aubrey Barker of Hopley's Nurseries. St Faith's Centre. -

"A Sharers' Repertory." Rethinking Theatrical

Syme, Holger Schott. "A Sharers’ Repertory." Rethinking Theatrical Documents in Shakespeare’s England. Ed. Tiffany Stern. London: The Arden Shakespeare, 2020. 33–51. Bloomsbury Collections. Web. 26 Sep. 2021. <http://dx.doi.org/10.5040/9781350051379.ch-002>. Downloaded from Bloomsbury Collections, www.bloomsburycollections.com, 26 September 2021, 08:28 UTC. Copyright © Tiffany Stern and contributors 2020. You may share this work for non-commercial purposes only, provided you give attribution to the copyright holder and the publisher, and provide a link to the Creative Commons licence. 2 A Sharers’ Repertory Holger Schott Syme Without Philip Henslowe, we would know next to nothing about the kinds of repertories early modern London’s resident theatre companies offered to their audiences. As things stand, thanks to the existence of the manuscript commonly known as Henslowe’s Diary , scholars have been able to contemplate the long lists of receipts and expenses that record the titles of well over 200 plays, most of them now lost. The Diary gives us some sense of the richness and diversity of this repertory, of the rapid turnover of plays, and of the kinds of investments theatre companies made to mount new shows. It also names a plethora of actors and other professionals associated with the troupes at the Rose. But, because the records are a fi nancier’s and theatre owner’s, not those of a sharer in an acting company, they do not document how a group of actors decided which plays to stage, how they chose to alternate successful shows, or what they, as actors, were looking for in new commissions. -

Redating Pericles: a Re-Examination of Shakespeare’S

REDATING PERICLES: A RE-EXAMINATION OF SHAKESPEARE’S PERICLES AS AN ELIZABETHAN PLAY A THESIS IN Theatre Presented to the Faculty of the University of Missouri-Kansas City in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree MASTER OF ARTS by Michelle Elaine Stelting University of Missouri Kansas City December 2015 © 2015 MICHELLE ELAINE STELTING ALL RIGHTS RESERVED REDATING PERICLES: A RE-EXAMINATION OF SHAKESPEARE’S PERICLES AS AN ELIZABETHAN PLAY Michelle Elaine Stelting, Candidate for the Master of Arts Degree University of Missouri-Kansas City, 2015 ABSTRACT Pericles's apparent inferiority to Shakespeare’s mature works raises many questions for scholars. Was Shakespeare collaborating with an inferior playwright or playwrights? Did he allow so many corrupt printed versions of his works after 1604 out of indifference? Re-dating Pericles from the Jacobean to the Elizabethan era answers these questions and reveals previously unexamined connections between topical references in Pericles and events and personalities in the court of Elizabeth I: John Dee, Philip Sidney, Edward de Vere, and many others. The tournament impresas, alchemical symbolism of the story, and its lunar and astronomical imagery suggest Pericles was written long before 1608. Finally, Shakespeare’s focus on father-daughter relationships, and the importance of Marina, the daughter, as the heroine of the story, point to Pericles as written for a young girl. This thesis uses topical references, Shakespeare’s anachronisms, Shakespeare’s sources, stylometry and textual analysis, as well as Henslowe’s diary, the Stationers' Register, and other contemporary documentary evidence to determine whether there may have been versions of Pericles circulating before the accepted date of 1608. -

The Elizabethan Age

The Elizabethan Age This royal throne of kings, this sceptred isle, This earth of majesty, this seat of Mars, This other Eden, demi-paradise, This fortress built by Nature for herself Against infection and the hand of war, This happy breed of men, this little world, This precious stone set in the silver sea, Which serves it in the office of a wall Or as a moat defensive to a house, Against the envy of less happier lands,- This blessed plot, this earth, this realm, this England. – Richard II, William Shakespeare DRAMA TEACHER ACADEMY © 2015 LINDSAY PRICE 1 INDEX THE ELIZABETHAN AGE What was going on during this time period? THE ELIZABETHAN THEATRE The theatres, the companies, the audiences. STAGING THE ELIZABETHAN PLAY How does it differ from modern staging? DRAMA TEACHER ACADEMY © 2015 LINDSAY PRICE 2 Facts About Elizabethan England • The population rose from 3 to 4 million. • This increase lead to widespread poverty. • Average life expectancy was 40 years of age. • Country largely rural, though there is growth in towns and cities. • The principal industry still largely agricultural with wool as its main export. But industries such as weaving started to take hold. • Society strongly divided along class lines. • People had to dress according to their class. • The colour purple was reserved for royalty. • The religion was Protestant-Anglican – the Church of England. • There was a fine if you didn’t attend church. • Only males went to school. • The school day could run from 6 am to 5 pm. • The middle class ate a diet of grains and vegetables – meat was a luxury saved for the rich, who surprisingly ate few vegetables. -

Hamlet (The New Cambridge Shakespeare, Philip Edwards Ed., 2E, 2003)

Hamlet Prince of Denmark Edited by Philip Edwards An international team of scholars offers: . modernized, easily accessible texts • ample commentary and introductions . attention to the theatrical qualities of each play and its stage history . informative illustrations Hamlet Philip Edwards aims to bring the reader, playgoer and director of Hamlet into the closest possible contact with Shakespeare's most famous and most perplexing play. He concentrates on essentials, dealing succinctly with the huge volume of commentary and controversy which the play has provoked and offering a way forward which enables us once again to recognise its full tragic energy. The introduction and commentary reveal an author with a lively awareness of the importance of perceiving the play as a theatrical document, one which comes to life, which is completed only in performance.' Review of English Studies For this updated edition, Robert Hapgood Cover design by Paul Oldman, based has added a new section on prevailing on a draining by David Hockney, critical and performance approaches to reproduced by permission of tlie Hamlet. He discusses recent film and stage performances, actors of the Hamlet role as well as directors of the play; his account of new scholarship stresses the role of remembering and forgetting in the play, and the impact of feminist and performance studies. CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY PRESS www.cambridge.org THE NEW CAMBRIDGE SHAKESPEARE GENERAL EDITOR Brian Gibbons, University of Munster ASSOCIATE GENERAL EDITOR A. R. Braunmuller, University of California, Los Angeles From the publication of the first volumes in 1984 the General Editor of the New Cambridge Shakespeare was Philip Brockbank and the Associate General Editors were Brian Gibbons and Robin Hood. -

TITUS ANDRONICUS: Know-The-Show Guide

The Shakespeare Theatre of New Jersey 2018 TITUS ANDRONICUS: Know-the-Show Guide Titus Andronicus by William Shakespeare Know-the-Show Audience Guide researched and written by the Education Department of Artwork by Scott McKowen The Shakespeare Theatre of New Jersey 2018 TITUS ANDRONICUS: Know-the-Show Guide In this Guide – The Life of William Shakespeare ............................................................................................... 2 – Titus Andronicus: Director’s Note .............................................................................................. 3 – Titus Andronicus: A Synopsis .................................................................................................... 5 – Who’s Who in the Play ............................................................................................................. 7 – Sources and History .................................................................................................................. 8 – The Peacham Drawing .............................................................................................................. 9 – Titus Andronicus: A Play for Our Time? ................................................................................... 10 – Commentary & Criticism ........................................................................................................ 11 – Theatre in Shakespeare’s Day .................................................................................................. 12 – In this Production .................................................................................................................. -

Pembroke's Men in 1592–3, Their Repertory and Touring Schedule

Issues in Review 129 22 Leland H. Carlson, Martin Marprelate, Gentleman: Master Job Throckmorton Laid Open in his Colours (San Marino: Huntington Library, 1981), 72–81; Donald J. McGinn, John Penry and the Marprelate Controversy (New Bruns- wick, NJ, 1966), 134. 23 John Laurence, A History of Capital Punishment (New York, 1963), 9; see also Naish, Death Comes to the Maiden, 9, and Frances E. Dolan, ‘“Gentlemen, I have one more thing to say”: Women on Scaffolds in England, 1563–1680’, Modern Philology 92 (1994), 166. Pembroke’s Men in 1592–3, Their Repertory and Touring Schedule Some years ago, during a seminar on theatre history at the annual meeting of the Shakespeare Association of America, someone asked plaintively, ‘What did bad companies play in the provinces?’ and Leeds Barroll quipped, ‘Bad quartos’. The belief behind the joke – that ‘bad’ quartos and failing companies went together – has seemed specifically true of the earl of Pembroke’s players in 1592–3. Pembroke’s Men played in the provinces, and plays later published that advertised their ownership have been assigned to the category of texts known as ‘bad’ quartos. Even so, the company had reasons to be considered ‘good’. They enjoyed the patronage of Henry Herbert, the earl of Pembroke, and gave two of the five performances at court during Christmas, 1592–3 (26 December, 6 January). Their players, though probably young, were talented and committed to the profession: Richard Burbage, who would become a star with the Chamberlain’s/King’s Men, was still acting within a year of his death in 1619; William Sly acted with the Chamberlain’s/King’s Men until his death in 1608; Humphrey Jeffes acted with the Admiral’s/Prince’s/Palsgrave’s Men, 1597–1615; Robert Pallant and Robert Lee, who played with Worcester’s/ Queen Anne’s Men, were still active in the 1610s. -

Was Robert Greene's “Upstart Crow” the Actor Edward Alleyn?

The Marlowe Society Was Robert Greene’s “Upstart Crow” Research Journal - Volume 06 - 2009 the actor Edward Alleyn? Online Research Journal Article Daryl Pinksen Was Robert Greene’s “Upstart Crow” the actor Edward Alleyn? "The first mention of William Shakespeare as a writer occurred in 1592 when Robert Greene singled him out as an actor-turned-playwright who had grown too big for his britches." Such is the claim made by all Shakespeare biographers. However, a closer look at the evidence reveals what appears to be an unfortunate case of mistaken identity. Near the end of Greene's Groatsworth of Wit (September 1592) 1, Robert Greene, in an address to three fellow playwrights widely agreed to be Christopher Marlowe, Thomas Nashe and George Peele, says that an actor he calls an "upstart Crow" has become so full of himself that he now believes he is the only "Shake-scene" in the country. This puffed-up actor even dares to write blank verse and imagines himself the equal of professional playwrights. In his address to Marlowe, Nashe, and Peele, Greene reminds them that actors owe their entire careers to writers. He warns his fellow playwrights that just as he has been abandoned by these actors, it could just as easily happen to them. He urges them not to trust the actors, especially the one he calls an "upstart Crow." Finally, he pleads with them to stop writing plays for the actors, whom he variously calls "Apes," "Antics," and "Puppets." Here is Greene's warning to his fellow playwrights [following immediately from Appendix B]: Base minded men all three of you, if by my misery you be not warned: for unto none of you (like me) sought those burres to cleave: those Puppets (I mean) that spake from our mouths, those Anticks garnished in our colours.