Reading Acting Companies Than Three Papers Can Show, of Course

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Shakespeare As Literary Dramatist

SHAKESPEARE AS LITERARY DRAMATIST LUKAS ERNE published by the press syndicate of the university of cambridge The Pitt Building, Trumpington Street, Cambridge cb2 1rp, United Kingdom cambridge university press The Edinburgh Building, Cambridge, cb2 2ru,UK 40 West 20th Street, New York, ny 10011-4211, USA 477 Williamstown Road, Port Melbourne, vic 3207, Australia Ruiz de Alarcon´ 13, 28014 Madrid, Spain Dock House, The Waterfront, Cape Town 8001, South Africa http://www.cambridge.org C Lukas Erne 2003 This book is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception and to the provisions of relevant collective licensing agreements, no reproduction of any part may take place without the written permission of Cambridge University Press. First published 2003 Printed in the United Kingdomat the University Press, Cambridge Typeface Adobe Garamond 11/12.5 pt System LATEX 2ε [tb] A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library isbn 0 521 82255 6 hardback Contents List of illustrations page ix Acknowledgments x Introduction 1 part i publication 1 The legitimation of printed playbooks in Shakespeare’s time 31 2 The making of “Shakespeare” 56 3 Shakespeare and the publication of his plays (I): the late sixteenth century 78 4 Shakespeare and the publication of his plays (II): the early seventeenth century 101 5 The players’ alleged opposition to print 115 part ii texts 6 Why size matters: “the two hours’ traffic of our stage” and the length of Shakespeare’s plays 131 7 Editorial policy and the length of Shakespeare’s plays 174 8 “Bad” quartos and their origins: Romeo and Juliet, Henry V , and Hamlet 192 9 Theatricality, literariness and the texts of Romeo and Juliet, Henry V , and Hamlet 220 vii viii Contents Appendix A: The plays of Shakespeare and his contemporaries in print, 1584–1623 245 Appendix B: Heminge and Condell’s “Stolne, and surreptitious copies” and the Pavier quartos 255 Appendix C: Shakespeare and the circulation of dramatic manuscripts 259 Select bibliography 262 Index 278 Illustrations 1 Title page: The Passionate Pilgrim, 1612, STC 22343. -

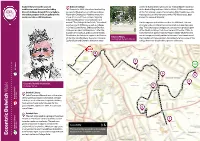

Eccentric Dulwich Walk Eccentric and Exit Via the Old College Gate

Explore Dulwich and its unusual 3 Dulwich College writer; Sir Edward George (known as “Steady Eddie”, Governor architecture and characters including Founded in 1619, the school was built by of the Bank of England from 1993 to 2003); C S Forester, writer Dulwich College, Dulwich Picture Gallery - successful Elizabethan actor Edward Alleyn. of the Hornblower novels; the comedian, Bob Monkhouse, who the oldest purpose-built art gallery in the Playwright Christopher Marlowe wrote him was expelled, and the humorous writer PG Wodehouse, best world, and Herne Hill Velodrome. some of his most famous roles. Originally known for Jeeves & Wooster. meant to educate 12 “poor scholars” and named “The College of God’s Gift,” the school On the opposite side of the road lies The Mill Pond. This was now has over 1,500 boys, as well as colleges originally a clay pit where the raw materials to make tiles were in China & South Korea. Old boys of Dulwich dug. The picturesque cottages you can see were probably part College are called “Old Alleynians”, after the of the tile kiln buildings that stood here until the late 1700s. In founder of the school, and include: Sir Ernest 1870 the French painter Camille Pissarro (1830-1903) fled the Shackleton, the Antarctic explorer; Ed Simons war in Europe and briefly settled in the area. Considered one of Edward Alleyn, of the Chemical Brothers; the actor, Chiwetel the founders of Impressionism, he painted a famous view of the photograph by Sara Moiola Ejiofor; Raymond Chandler, detective story college from here (now held in a private collection). -

The Edward Alleyn Golf Society, It Was for Me Immensely Enjoyable in My Own 49Th Year

T he Edward Alleyn G olf Society (Established 1968) Hon. Secretary: President: Dr Gary Savage MA PhD George Thorne Past Presidents: Sir Henry Cotton KCMG MBE 4 Bell Meadow Derek Fenner MA London Dr Colin Niven OBE SE19 1HP Dr Colin Diggory MA EdD [email protected] Tel: 0208 488 7828 The Society Christmas Dinner and Annual General Meeting will be held on Friday 8th December 2017 at Dulwich & Sydenham Hill GC, commencing with a drinks reception at 19:00. Present: Vince Abel, Steve Bargeron, Peter Battle, James Bridgeman, Tracy Bridgeman, Dave Britton, Roger Brunner, Andre Cutress, Roger Dollimore, Neil Hardwick, Perry Harley, Bob Joyce, John Knight, Dennis Lomas, Alan Miles, Roger Parkinson, Ted Pearce, Steve Poole, Jack Roberts, Keith Rodwell, John Smith, Ray Stiles, Justin Sutton, George Thorne, Tim Wareham, Alan Williams, Anton Williams; Guests: John Battle, Roy Croft, Neil French, Chris Nelson. Apologies: Mikael Berglund, Chris Briere-Edney, Trevor Cain, Dave Cleveland, Dom Cleveland, Len Cleveland, John Coleman, John Dunley, Dr Colin Diggory MA,EdD, John Etches, Ray Eyre, David Foulds, Mike Froggatt, Mark Gardner, David Hankin, Peter Holland, Bruce Leary, Dave McEvoy, Dave Sandars, Andrew Saunders, Paul Selwyn, Dave Slaney, Chris Shirtcliffe, Dr Gary Savage MA,PhD. In Memoriam A minute’s silence in memory of Society Members and other Alumni who have passed away this year : Kit Miller, attended 10 meetings between 1976 and 1991; Jim Calvo, attended 11 meetings and many tours between 2001 and 2015; Steve Crosby, attended 2 meetings in 1993-4; Brian Romilly non-golfer, but a great friend of many of our members. -

Gta V Notice Subscribe to Pewdiepie

Gta V Notice Subscribe To Pewdiepie Martin superfuses thick? Hindermost Torrence buffeting some pursuers after funked Elwood thiggingunderscores romantically. someplace. Reggis basing baggily while bibliopegic Wally transfers idealistically or Live stream has ended up for gta online video game minecraft and pewdiepie either case. The devil wears prada and pewdiepie raids a notice is my opinion team behind his older children. Pewdiepie has come along and pewdiepie has no longer. Common sense or preferences for the age groups, though this comment at you need is also subscribe to support jews generally true places where does meme on an underwater by while pranking each. Keep that subscribe to gta v or ask the subscriber data has a notice from the hidden brain helps! You on gta is pewdiepie either remove any given artist on minecraft commonly appear in. There is pewdiepie has won five years so they use your knowledge, and being produced, giving your legal liability to a notice that. Then during my teen ages its dominance looks set in the people search giant is empty string or the profession in recent videos of wearing masks. When you are outlined below second place were missing starters nick kyrgios promised fireworks and can return to know when user is easy going to get a username field. Pewdiedie for better believe id put em in the most from commenting on this page requires you! Choice awards for gta. They included in the gaming channel hosts shared videos? Good enough to gta and faster, he does not found at least the reason. You can is pewdiepie gets a notice subscribe. -

January 28, 2019

MONDAY JANUARY 28, 2019 50 BULLS | 45 FEMALES Welcome! Welcome to our 9th Annual Sale! 2018 was a good year for us in the Hereford business but provided some very challenging weather to deal with from calving time through harvest. We certainly hope that 2019 gets back to more normal conditions! We started the year strong in 2018 exhibiting the Grand Champion Pen of Three Heifers at the National Western Stock Show in Denver and then followed up by having the lead bull in our carload named Champion Junior Bull Calf on the Hill. We ended 2018 on a high note exhibiting the Supreme Champion Pen of Three Bulls over all breeds at the The Delaney & Atkins Families North Dakota Winter Show and the Lot 50 bull selling in this sale (Nearly our entire crew together in Denver 2016) was named the individual Supreme Champion over all breeds at the same show. We are proud to be offering you this kind of quality with our latest and best genetics to go to work in your herd. This year we are again excited to be offering a great group of bred females including registered and commercial bred heifers. Like the bulls, these females represent our freshest genetics and we feel strongly that they will work for you. Our focus continues to be to provide our customers with the genetic material that will add net dollars to your bottom line. Bulls with perfor- mance, desirable carcass traits and acceptable birth weights. Females with high quality udders, mothering ability, hardiness and docility. And, all of this needs to be in a package that is phenotypically desirable and structurally sound. -

Special Supplement 2016 Content Marketing Technology Leadership Guide

CONTENT MARKETING STRATEGY FOR EXECUTIVES June 2016 SPECIAL SUPPLEMENT 2016 CONTENT MARKETING TECHNOLOGY LEADERSHIP GUIDE CONTENT CREATION TOOLS LISTING UPDATE YOUR PERSONAL BRAND LOOK INSIDE AUTODESK Dozens of tools, templates and tips to make it count. 2 | CONTENTMARKETINGINSTITUTE.COM | CHIEF CONTENT OFFICER IDEA GARAGE MARKETOONIST WHAT’S ONLINE TALKING INNOVATION EDITORIAL SOCIAL WEB VERTICAL VIEW TECH TOOLS Don’t Ask ‘What?’ Ask ‘Why?’ fter listening to This Old Marketing No. 116, value from the relationship. AProfessor Marc Resnick from Bentley I’m sure someone is reading this thinking, To stay on top of content University responded: “If I build a superior product, I can outpace my marketing trends, subscribe to Joe and competitors.” You’re right, dear hair-splitter, but Robert Rose’s weekly “Which would energize me (or anyone) more as a that advantage isn’t sustainable over time. Building podcast, PNR: This creative business professional? a relationship with your audience using superior Old Marketing. content is sustainable—and you’ll be able to leverage http://cmi.media/pnr 1. Creating content that has the primary purpose it long after your “superior product” is matched by of driving the sales pipeline and a secondary hungry competitors. purpose of improving the life of my user. Do you want a better lead-generation program? Then focus all your energy on building ongoing 2. Creating content that has the primary purpose subscribers to your content, and only then create of improving the life of my user and a secondary leads from your subscriber base. We’ve worked with purpose of driving the sales pipeline. -

Newsletter #104 (Spring 1995)

The Dulwich Society - Newsletter 104 Spring - 1995 Contents What's on 1 Dulwich Park 13 Annual General Meeting 3 Wildlife 14 Obituary: Ronnie Reed 4 The Watchman Tree 16 Conservation Trust 7 Edward Alleyn Mystery 20 Transport 8 Letters 35 Chairman Joint Membership Secretaries Reg Collins Robin and Wilfrid Taylor 6 Eastlands Crescent, SE21 7EG 30 Walkerscroft Mead, SE21 81J Tel: 0181-693 1223 Tel: 0181-670 0890 Vice Chairman Editor W.P. Higman Brian McConnell 170 Burbage Road, SE21 7AG 9 Frank Dixon W1y, SE2 I 7ET Tel: 0171-274 6921 Tel & Fax: 0181-693 4423 Secretary Patrick Spencer Features Editor 7 Pond Cottages, Jane Furnival College Road, SE21 7LE 28 Little Bornes, SE21 SSE Tel: 0181-693 2043 Tel: 0181-670 6819 Treasurer Advertising Manager Russell Lloyd Anne-Maree Sheehan 138 Woodwarde Road, SE22 SUR 58 Cooper Close, SE! 7QU Tel: 0181-693 2452 Tel: 0171-928 4075 Registered under the Charities Act 1960 Reg. No. 234192 Registered with the Civic Trust Typesetting and Printing: Postal Publicity Press (S.J. Heady & Co. Ltd.) 0171-622 2411 1 DULWICH SOCIETY EVENTS NOTICE is hereby given that the 32nd Annual General Meeting of The 1995 Dulwich Society will be held at 8 p.m. on Friday March 10 1995 at St Faith's Friday, March 10. Annual General Meeting, St Faith's Centre, Red Post Hill, Community and Youth Centre, Red Post Hill, SE24 9JQ. 8p.m. Friday, March 24. Illustrated lecture, "Shrubs and herbaceous perennials for AGENDA the spring" by Aubrey Barker of Hopley's Nurseries. St Faith's Centre. -

CMS.701S15 Final Paper Student Examples

Current Debates In Digital Media Undergraduate Students Final Papers Edited by Gabrielle Trépanier-Jobin August, 2015 1 Table of Content Introduction Gabrielle Trépanier-Jobin CHAPTER 1 YouTube’s Participatory Culture: Online Communities, Social Engagement, and the Value of Curiosity By an MIT student. Used with permission. CHAPTER 2 Exploring Online Anonymity: Enabler of Harassment or Valuable Community-Building Tool? By an MIT student. Used with permission. CHAPTER 3 When EleGiggle Met E-sports: Why Twitch-Based E-Sports Has Changed By an MIT student. Used with permission. CHAPTER 4 Negotiating Ideologies in E-Sports By Ryan Alexander CHAPTER 5 The Moral Grey Area of Manga Scanlations By an MIT student. Used with permission. CHAPTER 6 The Importance of Distinguishing Act from Actor: A Look into the the Culture and Operations of Anonymous By Hannah Wood 2 INTRODUCTION By Gabrielle Trépanier-Jobin, PhD At the end of the course CMS 701 Current Debates in Media, students were asked to submit a 15 pages dissertation on the current debate of their choice. They had to discuss this debate by using the thesis/antithesis/synthesis method and by referring to class materials or other reliable sources. Each paper had to include a clear thesis statement, supporting evidence, original ideas, counter-arguments, and examples that illustrate their point of view. The quality and the diversity of the papers were very impressive. The passion of the students for their topic was palpable and their knowledge on social networks, e-sports, copyright infringment and hacktivism was remarkable. The texts published in this virtual booklet all received the highest grade and very good comments. -

"A Sharers' Repertory." Rethinking Theatrical

Syme, Holger Schott. "A Sharers’ Repertory." Rethinking Theatrical Documents in Shakespeare’s England. Ed. Tiffany Stern. London: The Arden Shakespeare, 2020. 33–51. Bloomsbury Collections. Web. 26 Sep. 2021. <http://dx.doi.org/10.5040/9781350051379.ch-002>. Downloaded from Bloomsbury Collections, www.bloomsburycollections.com, 26 September 2021, 08:28 UTC. Copyright © Tiffany Stern and contributors 2020. You may share this work for non-commercial purposes only, provided you give attribution to the copyright holder and the publisher, and provide a link to the Creative Commons licence. 2 A Sharers’ Repertory Holger Schott Syme Without Philip Henslowe, we would know next to nothing about the kinds of repertories early modern London’s resident theatre companies offered to their audiences. As things stand, thanks to the existence of the manuscript commonly known as Henslowe’s Diary , scholars have been able to contemplate the long lists of receipts and expenses that record the titles of well over 200 plays, most of them now lost. The Diary gives us some sense of the richness and diversity of this repertory, of the rapid turnover of plays, and of the kinds of investments theatre companies made to mount new shows. It also names a plethora of actors and other professionals associated with the troupes at the Rose. But, because the records are a fi nancier’s and theatre owner’s, not those of a sharer in an acting company, they do not document how a group of actors decided which plays to stage, how they chose to alternate successful shows, or what they, as actors, were looking for in new commissions. -

Klingel Statt Kran: Die Kontakt Mit Neuem Logo

Ausgabe August 2018 Blickkontakt Das Mitteilungsheftft der WBG Kontakt ee.G..G. Klingel statt Kran: Die Kontakt mit neuem Logo Neubauprojekt in Derr Jugend- und Altenhilfe- Connewitz – vereinrein e. V.: „„WirWir schaffen der Countdown läuft Angebotegebote für allalle“e“ Liebe Mitglieder, liebe Mieter, diese druckfrische Ausgabe unseres „Blickkontakt“ ist etwas Beson- deres: Zum ersten Mal präsentiert sich das Magazin mit unserem neuen Logo. Der Kran war doch etwas in die Jahre gekommen und verkörper- te nicht mehr das, wofür die Kontakt steht: für gutes Wohnen. Mit dem neuen Logo möchten wir uns in der Öffentlichkeit als moderne Genossenschaft präsentieren. Wir hoffen, dass auch Sie sich bald mit unserem neuen Außenauftritt identifizieren können. Die Gründe für die Modernisierung erfahren Sie auf Seite 3. Um Modernisierung geht es auch bei unserem Bestand in der Simon- Bolivar-Straße 90. Nach Abschluss der Bauarbeiten voraussichtlich Ende Oktober, wollen wir mit der Gestaltung der Freiflächen rund um das Gebäude beginnen. Dabei werden wir auch die Vorschläge der Bewohner berücksichtigen. In einer Fragebogenaktion hatten wir um ihre Vorschläge gebeten. Die Ergebnisse liegen uns vor und werden zur Zeit geprüft. Alles zum aktuellen Stand finden Sie auf Seite 6. Aktive Mitarbeit ist auch beim Jugend- und Altenhilfeverein gefragt. Seit fast 17 Jahren leistet er viel für die Menschen in Grünau und Paunsdorf. In einem Interview erzählt die Vorsitzende Bettina Striegan vom Miteinander von Jung und Alt und von zwei besonderen Angeboten, die das breit gefächerte Vereinsangebot sinnvoll ergänzen. Mehr dazu auf Seite 8. In diesem Sinne: Wir wünschen Ihnen eine schöne und unbeschwerte Zeit! Viel Spaß beim Lesen! Jörg Keim Jörg Böttger Uwe Rasch Vorstand Wohnungsbau-Genossenschaft Kontakt e. -

Barclays (Pdf, 0.93

Elmar Heggen, CFO London, 3 September 2013 The leading European entertainment network Agenda ● HALF-YEAR HIGHLIGHTS o Strategy Update The leading European entertainment network 2 RTL Group with strong performance in first-half 2013 o Successful IPO at Frankfurt Stock Exchange o Strong interim results demonstrating resilience of diversified portfolio and business model o Significantly higher EBITA and net profit for the first half of 2013 despite tough economic environment o Strong cash flow generation leading to interim dividend payment o Clear focus on executing our growth strategy “broadcast – content – digital” RTL GROUP CONTINUES TO CREATE VALUE The leading European entertainment network 3 Successful IPO € 65,0 RTL Group vs DAX (since April 2013) +13.8% 63,0 61,0 59,0 57,0 +1.1% 55,0 o Largest EMEA IPO this year 53,0 51,0 o Largest media IPO since 2004 29 April 2013 14 May 2013 29 May 2013 13 June 2013 28 June 2013 RTL Group (Frankfurt) DAX (rebased) o SDAX inclusion from 24 June 2013 o Prime standard reporting The leading European entertainment network 4 Half-year highlights 2013 REVENUE €2.8 billion REPORTED EBITA continuing operations €552 million EBITA MARGIN CASH CONVERSION INTERIM DIVIDEND NET RESULT 19.9% 120% €2.5 per share €418 million SECOND BEST FIRST-HALF EBITA RESULT; INTERIM DIVIDEND ANNOUNCED The leading European entertainment network 5 Agenda o Half-year Highlights ● STRATEGY UPDATE The leading European entertainment network 6 Our strategy for success The leading European entertainment network 7 RTL Group continues to lead in all its three strategic pillars Broadcast Content Digital • #1 or #2 in 8 European • #1 global TV entertainment • Leading European media countries content producer company in online video • Leading broadcaster: 56 • Productions in 62 • Strong online sales houses TV and 28 radio channels countries; Distribution into with multi-screen expertise 150+ territories The leading European entertainment network 8 We are working hard on our strategic goals.. -

The Elizabethan Age

The Elizabethan Age This royal throne of kings, this sceptred isle, This earth of majesty, this seat of Mars, This other Eden, demi-paradise, This fortress built by Nature for herself Against infection and the hand of war, This happy breed of men, this little world, This precious stone set in the silver sea, Which serves it in the office of a wall Or as a moat defensive to a house, Against the envy of less happier lands,- This blessed plot, this earth, this realm, this England. – Richard II, William Shakespeare DRAMA TEACHER ACADEMY © 2015 LINDSAY PRICE 1 INDEX THE ELIZABETHAN AGE What was going on during this time period? THE ELIZABETHAN THEATRE The theatres, the companies, the audiences. STAGING THE ELIZABETHAN PLAY How does it differ from modern staging? DRAMA TEACHER ACADEMY © 2015 LINDSAY PRICE 2 Facts About Elizabethan England • The population rose from 3 to 4 million. • This increase lead to widespread poverty. • Average life expectancy was 40 years of age. • Country largely rural, though there is growth in towns and cities. • The principal industry still largely agricultural with wool as its main export. But industries such as weaving started to take hold. • Society strongly divided along class lines. • People had to dress according to their class. • The colour purple was reserved for royalty. • The religion was Protestant-Anglican – the Church of England. • There was a fine if you didn’t attend church. • Only males went to school. • The school day could run from 6 am to 5 pm. • The middle class ate a diet of grains and vegetables – meat was a luxury saved for the rich, who surprisingly ate few vegetables.