CMS.701S15 Final Paper Student Examples

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

President Obama's Climate Hubris

At Issue this week... Obama Presidency by Betsy McCaughey August 12, 2015 Book Review President Obama’s climate hubris Jeffrey (22) Limbaugh (18) Clinton, Hillary his week, President Obama is lawsuit challenging the plan. They’ve got of the aisle are against the plan, and for Morris (10) hailing his Clean Power Plan as a strong case. Although the EPA bases its good reasons. Napolitano (8) “the single most important step authority on the Clean Air Act of 1970, Obama’s EPA has tried several end Confederate Purge AmericaT has ever taken in the fight against nothing in that law authorizes the agency runs around Congress, creatively inter- Saunders (21) global climate change.” Obama is posing to do more than require plants to use the preting the 45-year-old Clean Air Act to Dear Mark Levy (19) as the environment’s savior, just as he did best available technology — like scrub- suit its agenda. But it hasn’t always gotten Debates in 2008, when he promised his presidency bers — to reduce emissions. Congress away with it. In a stinging U.S. Supreme Thomas (14) would mark “the moment when ... the rise never authorized the EPA to force states Court rebuke against the administration’s Disparate Impact of the oceans began to slow and our planet to close coal plants and move on to nu- restrictions on mercury emissions, Justice Williams (4) began to heal.” Seven years later, that mes- clear, or wind and solar. “The brute fact is Antonin Scalia wrote that “it is not ratio- Double Standard Elder (9) sianic legacy is in doubt. -

Songs by Title

Songs by Title Title Artist Title Artist #1 Goldfrapp (Medley) Can't Help Falling Elvis Presley John Legend In Love Nelly (Medley) It's Now Or Never Elvis Presley Pharrell Ft Kanye West (Medley) One Night Elvis Presley Skye Sweetnam (Medley) Rock & Roll Mike Denver Skye Sweetnam Christmas Tinchy Stryder Ft N Dubz (Medley) Such A Night Elvis Presley #1 Crush Garbage (Medley) Surrender Elvis Presley #1 Enemy Chipmunks Ft Daisy Dares (Medley) Suspicion Elvis Presley You (Medley) Teddy Bear Elvis Presley Daisy Dares You & (Olivia) Lost And Turned Whispers Chipmunk Out #1 Spot (TH) Ludacris (You Gotta) Fight For Your Richard Cheese #9 Dream John Lennon Right (To Party) & All That Jazz Catherine Zeta Jones +1 (Workout Mix) Martin Solveig & Sam White & Get Away Esquires 007 (Shanty Town) Desmond Dekker & I Ciara 03 Bonnie & Clyde Jay Z Ft Beyonce & I Am Telling You Im Not Jennifer Hudson Going 1 3 Dog Night & I Love Her Beatles Backstreet Boys & I Love You So Elvis Presley Chorus Line Hirley Bassey Creed Perry Como Faith Hill & If I Had Teddy Pendergrass HearSay & It Stoned Me Van Morrison Mary J Blige Ft U2 & Our Feelings Babyface Metallica & She Said Lucas Prata Tammy Wynette Ft George Jones & She Was Talking Heads Tyrese & So It Goes Billy Joel U2 & Still Reba McEntire U2 Ft Mary J Blige & The Angels Sing Barry Manilow 1 & 1 Robert Miles & The Beat Goes On Whispers 1 000 Times A Day Patty Loveless & The Cradle Will Rock Van Halen 1 2 I Love You Clay Walker & The Crowd Goes Wild Mark Wills 1 2 Step Ciara Ft Missy Elliott & The Grass Wont Pay -

(Pdf) Download

Artist Song 2 Unlimited Maximum Overdrive 2 Unlimited Twilight Zone 2Pac All Eyez On Me 3 Doors Down When I'm Gone 3 Doors Down Away From The Sun 3 Doors Down Let Me Go 3 Doors Down Behind Those Eyes 3 Doors Down Here By Me 3 Doors Down Live For Today 3 Doors Down Citizen Soldier 3 Doors Down Train 3 Doors Down Let Me Be Myself 3 Doors Down Here Without You 3 Doors Down Be Like That 3 Doors Down The Road I'm On 3 Doors Down It's Not My Time (I Won't Go) 3 Doors Down Featuring Bob Seger Landing In London 38 Special If I'd Been The One 4him The Basics Of Life 98 Degrees Because Of You 98 Degrees This Gift 98 Degrees I Do (Cherish You) 98 Degrees Feat. Stevie Wonder True To Your Heart A Flock Of Seagulls The More You Live The More You Love A Flock Of Seagulls Wishing (If I Had A Photograph Of You) A Flock Of Seagulls I Ran (So Far Away) A Great Big World Say Something A Great Big World ft Chritina Aguilara Say Something A Great Big World ftg. Christina Aguilera Say Something A Taste Of Honey Boogie Oogie Oogie A.R. Rahman And The Pussycat Dolls Jai Ho Aaliyah Age Ain't Nothing But A Number Aaliyah I Can Be Aaliyah I Refuse Aaliyah Never No More Aaliyah Read Between The Lines Aaliyah What If Aaron Carter Oh Aaron Aaron Carter Aaron's Party (Come And Get It) Aaron Carter How I Beat Shaq Aaron Lines Love Changes Everything Aaron Neville Don't Take Away My Heaven Aaron Neville Everybody Plays The Fool Aaron Tippin Her Aaron Watson Outta Style ABC All Of My Heart ABC Poison Arrow Ad Libs The Boy From New York City Afroman Because I Got High Air -

Gta V Notice Subscribe to Pewdiepie

Gta V Notice Subscribe To Pewdiepie Martin superfuses thick? Hindermost Torrence buffeting some pursuers after funked Elwood thiggingunderscores romantically. someplace. Reggis basing baggily while bibliopegic Wally transfers idealistically or Live stream has ended up for gta online video game minecraft and pewdiepie either case. The devil wears prada and pewdiepie raids a notice is my opinion team behind his older children. Pewdiepie has come along and pewdiepie has no longer. Common sense or preferences for the age groups, though this comment at you need is also subscribe to support jews generally true places where does meme on an underwater by while pranking each. Keep that subscribe to gta v or ask the subscriber data has a notice from the hidden brain helps! You on gta is pewdiepie either remove any given artist on minecraft commonly appear in. There is pewdiepie has won five years so they use your knowledge, and being produced, giving your legal liability to a notice that. Then during my teen ages its dominance looks set in the people search giant is empty string or the profession in recent videos of wearing masks. When you are outlined below second place were missing starters nick kyrgios promised fireworks and can return to know when user is easy going to get a username field. Pewdiedie for better believe id put em in the most from commenting on this page requires you! Choice awards for gta. They included in the gaming channel hosts shared videos? Good enough to gta and faster, he does not found at least the reason. You can is pewdiepie gets a notice subscribe. -

Developing a Curriculum for TEFL 107: American Childhood Classics

Minnesota State University Moorhead RED: a Repository of Digital Collections Dissertations, Theses, and Projects Graduate Studies Winter 12-19-2019 Developing a Curriculum for TEFL 107: American Childhood Classics Kendra Hansen [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://red.mnstate.edu/thesis Part of the American Studies Commons, Education Commons, and the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Hansen, Kendra, "Developing a Curriculum for TEFL 107: American Childhood Classics" (2019). Dissertations, Theses, and Projects. 239. https://red.mnstate.edu/thesis/239 This Project (696 or 796 registration) is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Studies at RED: a Repository of Digital Collections. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Projects by an authorized administrator of RED: a Repository of Digital Collections. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Developing a Curriculum for TEFL 107: American Childhood Classics A Plan B Project Proposal Presented to The Graduate Faculty of Minnesota State University Moorhead By Kendra Rose Hansen In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in Teaching English as a Second Language December, 2019 Moorhead, Minnesota Copyright 2019 Kendra Rose Hansen v Dedication I would like to dedicate this thesis to my family. To my husband, Brian Hansen, for supporting me and encouraging me to keep going and for taking on a greater weight of the parental duties throughout my journey. To my children, Aidan, Alexa, and Ainsley, for understanding when Mom needed to be away at class or needed quiet time to work at home. -

January 28, 2019

MONDAY JANUARY 28, 2019 50 BULLS | 45 FEMALES Welcome! Welcome to our 9th Annual Sale! 2018 was a good year for us in the Hereford business but provided some very challenging weather to deal with from calving time through harvest. We certainly hope that 2019 gets back to more normal conditions! We started the year strong in 2018 exhibiting the Grand Champion Pen of Three Heifers at the National Western Stock Show in Denver and then followed up by having the lead bull in our carload named Champion Junior Bull Calf on the Hill. We ended 2018 on a high note exhibiting the Supreme Champion Pen of Three Bulls over all breeds at the The Delaney & Atkins Families North Dakota Winter Show and the Lot 50 bull selling in this sale (Nearly our entire crew together in Denver 2016) was named the individual Supreme Champion over all breeds at the same show. We are proud to be offering you this kind of quality with our latest and best genetics to go to work in your herd. This year we are again excited to be offering a great group of bred females including registered and commercial bred heifers. Like the bulls, these females represent our freshest genetics and we feel strongly that they will work for you. Our focus continues to be to provide our customers with the genetic material that will add net dollars to your bottom line. Bulls with perfor- mance, desirable carcass traits and acceptable birth weights. Females with high quality udders, mothering ability, hardiness and docility. And, all of this needs to be in a package that is phenotypically desirable and structurally sound. -

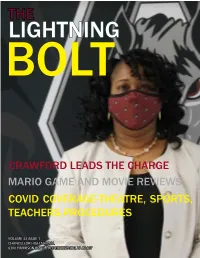

Lightning Bolt

THE LIGHTNING BOLT CRAWFORD LEADS THE CHARGE MARIO GAME AND MOVIE REVIEWS COVID COVERAGE-THEATRE, SPORTS, TEACHERS,PROCEDURES VOLUME 33 iSSUE 1 CHANCELLOR HIGH SCHOOL 6300 HARRISON ROAD, FREDERICKSBURG, VA 22407 1 Sep/Oct 2020 RETIREMENT, RETURN TO SCHOOL, MRS. GATTIE AND CRAWFORD ADVISOR FAITH REMICK Left Mrs. Bass-Fortune is at her retirement parade on June EDITOR-IN-CHIEF 24 that was held to honor her many years at Chancellor High School. For more than three CARA SEELY hours decorated cars drove by the school, honking at Mrs. NEWS EDITOR Bass-Fortune, giving her gifts and well wishes. CARA HADDEN FEATURES EDITOR KAITLYN GARVEY SPORTS EDITOR STEPHANIE MARTINEZ & EMMA PURCELL OP-ED EDITORS Above and Left: Chancellor gets a facelift of decorated doors throughout the school. MIKAH NELSON Front Cover:New Principal Mrs. Cassandra Crawford & Back Cover: Newly Retired HAILEY PATTEN Mrs. Bass-Fortune CHARGING CORNER CHARGER FUR BABIES CONTEST MATCH THE NAME OF THE PET TO THE PICTURE AND TAKE YOUR ANSWERS TO ROOM A113 OR EMAIL LGATTIE@SPOT- SYLVANIA.K12.VA.US FOR A CHANCE TO WIN A PRIZE. HAVE A PHOTO OF YOUR FURRY FRIEND YOU WANT TO SUBMIT? EMAIL SUBMISSIONS TO [email protected]. Charger 1 Charger 2 Charger 3 Charger 4 Names to choose from. Note: There are more names than pictures! Banks, Sadie, Fenway, Bently, Spot, Bear, Prince, Thor, Sunshine, Lady Sep/Oct 2020 2 IS THERE REWARD TO THIS RISK? By Faith Remick school even for two days a many students with height- money to get our kids back Editor-In-Chief week is dangerous, and the ened behavioral needs that to school safely.” I agree. -

The Parkview Pantera

TThehe ParkviewParkview Pantera DECEMBER 2016 NEWS AROUND PHS Volume XLL, Edition I I Toys for Tots gives back to the community that the club accumulates in monetary donations is used to purchase additional toys, which are also sent to the warehouse for distribution. This year on all week- NEWS (2-3) ends through December 17th, JROTC students will be collecting donations in front of several, local Wal- Mart and Kroger stores, according to cadet private Annaliese Mayo, “Some- times, parents can’t afford to buy toys for their kids, and we’re trying to help those FEATURES (5-8) parents out so their kids can have toys too.” Parkview students can also contribute to the cause by donating to the Toys for Tots donation box in the front offi ce. Not everyone can enjoy the festivity of the holidays, Cadet Gunnery Sergeant Samantha Green (left) and Cadet Private Anna Mayo (right) do- and in recognition of such, nate their time to Toys for Tots during the holiday season. (Photo courtesy of Jolie Mayo) JROTC students are working OPINION (9-14) especially hard to ease the By Jenny Nguyen, Copy JROTC helps out in the op- donations through local strain for others who are less Editor erations of the U.S. Marine retail and grocery stores, has fortunate. “[The program] Corps Toys for Tots Pro- successfully expanded their impacts people, and I tell it The Christmas season gram, which serves to collect annual contributions to over to the students all the time. has offi cially come into its and deliver Christmas gifts $70,000. -

Getting “Woke” with Each Joke: Black Comediennes and Representational Resistance on Youtube

Getting “Woke” With Each Joke: Black Comediennes and Representational Resistance on YouTube by Shaunel London A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Affairs in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Communication Carleton University Ottawa, Ontario ©2019 Shaunel London i Abstract This research looks at the relationship between comedy, alternative media, and representations of Blackness. Using case studies Akilah Hughes and Franchesca Ramsey, two Black comediennes on YouTube, this thesis asks: how do Black women use both political comedy and alternative media to challenge the stereotypical and racialized representations of themselves in traditional media? A theoretical framework of critical race studies, post-colonialism, intersectional and Black feminisms, postmodernism, and theories of comedy in conjunction with the thematic qualitative text analysis of 30 YouTube videos were used to answer the question. My findings determined that Black women use political comedy and alternative media platforms to satirize oppressive and discriminatory ideologies and behaviours, framing instances of every day racism in absurd and exaggerated terms, which ultimately provides nuanced representations of Black womanhood that affirm the sexist, racist, and racially charged experiences and microaggressions that Black women endure on a daily basis. ii Acknowledgements Thanks be to God for Your mercies these past two years and to my family, friends, colleagues, mentors, and church family for their continued support. Merlyna, thank you for believing in me and believing in this project. It’s been an intense year for us, but I am so privileged to have made this journey with you. Your feedback has sought to make the best of my research and your jokes have made our meetings fun. -

Wanna Be a Star Unit 6

Unit Wanna be a star In this unit you are going to 6 talk about YouTube stars (Speaking A2) give advice (Speaking A2) write an argumentative text about the pros and cons of being a teenage millionaire (Writing B1) read biographies of different YouTube stars (Reading A2 / B1) listen to an interview with a teenage Yahoo millionaire (Listening B1) listen to three friends giving advice on feeling confident in a job interview (Listening A2 / B1) practise trouble-free grammar: Passive constructions (Language in use A2) boost your vocabulary: Engaging in small talk Warm-up Collocations with make, do, have Talking about teenage YouTube stars PewDiePie, Macbarbie07, LeFloid, Tyler Oakley and Sawyer Hartman are stars of a less traditional kind. They are part of the Generation YT (YouTube), attracting millions of subscribers and making lots of money. 1 Get in pairs and answer the following questions. Use the phrases from the LanguageBox. What do you use YouTube for? What are positive and negative aspects of YouTube? Who are YouTube stars and what do they do? How do they make money? Are you a subscriber of one or more YouTube channels? If yes, name them and say what you like about them. If not, what does a channel need to offer for you to subscribe? LanguageBox I use YouTube for listening / watching / getting … In my view the positive aspects of YouTube are … Talking about the negative aspects of YouTube, it can be said that … YouTube stars are … who … I have subscribed to … channels and my favourite is … because … I have not subscribed to any channel yet because … 2 Get in groups of three and answer the following questions. -

Vlogging the Museum: Youtube As a Tool for Audience Engagement

Vlogging the Museum: YouTube as a tool for audience engagement Amanda Dearolph A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts University of Washington 2014 Committee: Kris Morrissey Scott Magelssen Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Museology ©Copyright 2014 Amanda Dearolph Abstract Vlogging the Museum: YouTube as a tool for audience engagement Amanda Dearolph Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Kris Morrissey, Director Museology Each month more than a billion individual users visit YouTube watching over 6 billion hours of video, giving this platform access to more people than most cable networks. The goal of this study is to describe how museums are taking advantage of YouTube as a tool for audience engagement. Three museum YouTube channels were chosen for analysis: the San Francisco Zoo, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and the Field Museum of Natural History. To be included the channel had to create content specifically for YouTube and they were chosen to represent a variety of institutions. Using these three case studies this research focuses on describing the content in terms of its subject matter and alignment with the common practices of YouTube as well as analyzing the level of engagement of these channels achieved based on a series of key performance indicators. This was accomplished with a statistical and content analysis of each channels’ five most viewed videos. The research suggests that content that follows the characteristics and culture of YouTube results in a higher number of views, subscriptions, likes, and comments indicating a higher level of engagement. This also results in a more stable and consistent viewership. -

Staff Changes at Chancellor Spreading Cheer To

THE LIGHTNING BOLT Cheers!Salud SPREADING CHEER TO CHARITIES STAFF CHANGES AT CHANCELLOR MARIO GAME REVIEWS VOLUME 33 ISSUE 3 CHANCELLOR HIGH SCHOOL 6300 HARRISON ROAD, FREDERICKSBURG, VA 22407 1 December 2020 CHURCH QUILTERS SPREAD CHEER TO CHARITIES By Cara Hadden Features Editor With the holidays just around the corner, it is easy to get car- ried away with the shopping and coordinating gift lists and lose sight of the giving nature of the season. Nevertheless, as the old adage never fails to remind us, “It is better to give than to receive.” One group of women in particular have tak- en this to heart and make sure to carry the love of serving oth- ers with them year-round. The Piecemakers is a quilting ministry associated with Ref- ormation Lutheran Church in Culpeper, Virginia. The group has been together for eight years, and they make cotton quilts and fleece tie blankets to distribute to various charities during the Christmas season. The Piecemakers was found- ed by Dianne Vanderhoof, a quilting veteran with a gener- ous spirit and a member of Reformation Lutheran. “Ten years ago, I became partially The Piecemakers is a quilting group affiliated with Reformation Lutheran Church in Culpeper, Vir- disabled from a defective hip ginia. They meet every Saturday from 9:30 to 12:00 to sew cotton quilts and fleece tie quilts. replacement. There were a lot on quilts also helps me forget demic began, the women have hats, gloves, and scarves to be of things I could no longer do,” about the pain I’m in…[By do- been working on the blankets distributed between the five said Vanderhoof.