Biographical Description for the Historymakers® Video Oral History with Katie Booth

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

What Made Nonviolent Protest Effective During the Civil Rights Movement?

NEW YORK STATE SOCIAL STUDIES RESOURCE TOOLKIT 5011th Grade Civil Rights Inquiry What Made Nonviolent Protest Effective during the Civil Rights Movement? © Bettmann / © Corbis/AP Images. Supporting Questions 1. What was tHe impact of the Greensboro sit-in protest? 2. What made tHe Montgomery Bus Boycott, BirmingHam campaign, and Selma to Montgomery marcHes effective? 3. How did others use nonviolence effectively during the civil rights movement? THIS WORK IS LICENSED UNDER A CREATIVE COMMONS ATTRIBUTION- NONCOMMERCIAL- SHAREALIKE 4.0 INTERNATIONAL LICENSE. 1 NEW YORK STATE SOCIAL STUDIES RESOURCE TOOLKIT 11th Grade Civil Rights Inquiry What Made Nonviolent Protest Effective during the Civil Rights Movement? 11.10 SOCIAL AND ECONOMIC CHANGE/DOMESTIC ISSUES (1945 – PRESENT): Racial, gender, and New York State socioeconomic inequalities were addressed By individuals, groups, and organizations. Varying political Social Studies philosophies prompted debates over the role of federal government in regulating the economy and providing Framework Key a social safety net. Idea & Practices Gathering, Using, and Interpreting Evidence Chronological Reasoning and Causation Staging the Discuss tHe recent die-in protests and tHe extent to wHicH tHey are an effective form of nonviolent direct- Question action protest. Supporting Question 1 Supporting Question 2 Supporting Question 3 Guided Student Research Independent Student Research What was tHe impact of tHe What made tHe Montgomery Bus How did otHers use nonviolence GreensBoro sit-in protest? boycott, the Birmingham campaign, effectively during tHe civil rights and tHe Selma to Montgomery movement? marcHes effective? Formative Formative Formative Performance Task Performance Task Performance Task Create a cause-and-effect diagram tHat Detail tHe impacts of a range of actors Research the impact of a range of demonstrates the impact of the sit-in and tHe actions tHey took to make tHe actors and tHe effective nonviolent protest by the Greensboro Four. -

“Who Speaks for Chicago?” Civil Rights, Community Organization and Coalition, 1910-1971 by Michelle Kimberly Johnson Thesi

“Who Speaks for Chicago?” Civil Rights, Community Organization and Coalition, 1910-1971 By Michelle Kimberly Johnson Fig. 1. Bernard J. Kleina, 1966 Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Bachelor of Arts In the Department of History at Brown University Thesis Advisor: Françoise Hamlin Friday, April 8, 2016 I am writing this thesis as a Black, biracial, woman of color. My Black paternal grandparents spent most of their lives on the South Side of Chicago, my father grew up there, and I grew up in Waukegan, Illinois, a mixed-income suburb fifty miles north of the city. This project is both extremely personal and political in nature. As someone working toward a future in academic activism and who utilizes a historical lens to do that work, the question of how to apply the stories and lessons of the past to the present, both as an intellectual project and a practical means of change, is always at the forefront. 2 Table of Contents Acknowledgments ...........................................................................................................................4 Introduction .....................................................................................................................................7 Chapter 1 Establishing Identity: The Great Migration and Early Civil Rights Organizing, 1900-1960 .......24 Chapter 2 Coordinated Efforts: The Battle for Better Schools, 1960-1965 ..................................................52 Chapter 3 End the Slums: Martin Luther King, Jr., 1966, and -

Martin Luther King Jr

Martin Luther King Jr. Martin Luther King Jr. (born Michael King Jr.; January 15, 1929 – April 4, 1968) was an American Baptist minister and activist who The Reverend became the most visible spokesperson and leader in the American civil rights movement from 1955 until his assassination in 1968. King Martin Luther King Jr. advanced civil rights through nonviolence and civil disobedience, inspired by his Christian beliefs and the nonviolent activism of Mahatma Gandhi. He was the son of early civil rights activist Martin Luther King Sr. King participated in and led marches for blacks' right to vote, desegregation, labor rights, and other basic civil rights.[1] King led the 1955 Montgomery bus boycott and later became the first president of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC). As president of the SCLC, he led the unsuccessful Albany Movement in Albany, Georgia, and helped organize some of the nonviolent 1963 protests in Birmingham, Alabama. King helped organize the 1963 March on Washington, where he delivered his famous "I Have a Dream" speech on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial. The SCLC put into practice the tactics of nonviolent protest with some success by strategically choosing the methods and places in which protests were carried out. There were several dramatic stand-offs with segregationist authorities, who sometimes turned violent.[2] FBI King in 1964 Director J. Edgar Hoover considered King a radical and made him an 1st President of the Southern Christian object of the FBI's COINTELPRO from 1963, forward. FBI agents investigated him for possible communist ties, recorded his extramarital Leadership Conference affairs and reported on them to government officials, and, in 1964, In office mailed King a threatening anonymous letter, which he interpreted as an attempt to make him commit suicide.[3] January 10, 1957 – April 4, 1968 On October 14, 1964, King won the Nobel Peace Prize for combating Preceded by Position established racial inequality through nonviolent resistance. -

MFDP Insider's Newsletter (Re Jackson Protests)

{ The M1ss1ss1pp1 Freedom Democratic Party ":lNSIDER 'S NEWSLETTER" Thursday, June 17 TO Ot!R BROTl!ERS AND SISTERS IN JA.IL--WE A1!E STEPP:lNG UP Ot!R PROTEST CAMPAIGN. ' '1!liE STREETS OF JACitSON WILL RIIIJ""WITH THE SOUND OP FREEDOM. THE WHOLE NATION KNOWS WHERE you ABE AHQ WHY vou ARE THERE KREP np THH s _piBIT-t"BB aBE COMING F'DP DECLARES "D·D.AY" ON FRIDAY, CHICAGO MOVEMENT SYMPATHIZERS ,PROM ALL OVER THE TI!LIWRAPRS St1PPOR!l' COtiN'l'RY EXPECTED. Following 1a the text of a text of The BOP will continue its demonstra a telegram to the FDP from the tion activities protesting the il oordinating Committee of Community legal government of Mississippi O~gan1za t1 ons, Albert Raby, chair with a massive "Demonstration day" man. The group bas been actively ef~ort this Friday. The call has demonstrating, with 'p'icket lines gdne out for all sympathizers from and sit-ins, protesting the re across the country to come to Jaok hiring of School Superinten<l.ent so.n for the march. Benjamin Willi&. In a week of ac t1vity close to 550 demonstrators "Friday we wUl rpull every strategy have been arrested. we know how in the city of Jackson. We will .do whatever the spir1t teills "Oree.ttnga from the Chioago move us to do Friday, • a party spokesman ment in the 11 St poi1ce station told a news conference yester<l.ay. to our Drotbe.rs and sistera in the Jackson Jail. In M1ss1asiPP.1 and Jame.a Farmer, CORE National Direc Chicago, we shall overcome ." t or, plane to Join with PDP demon (signed) Al Raby strators and Dick Gregory, current Dick Gregory ly active 1n Chicago demonstrations, says that 1f he is not busy 1n the Yesterday the Chicago group focuaed Chicago Jail, he will be glad to ita demonstre t1on. -

Organizations Relevant to the Status of Defacto Segregation in the Chicago Public Schools

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 029 077 U0 008 338 De Facto School Segregation; Hearings Before A Special Subcommittee on Investigation of De Facto Racial Segregation in Chicago Public Schools (Washington, D.C., July 27-28, 1965). Congress of the U.S., Washington, D.C. House Committee on Education and Labor. Pub Date Jul 65 Note- 368p. EDRS Price MF-SI.50 HC-SI8.50 Descriptors-*Defacto Segregation,Federal Government, *Northern Schools, *PublicSchools, *School Segregation, *Urban Schools Identifiers-Chicago The document consists of the testimony given at Congressional hearings in 1965. Included are statements by educators, labor leaders, and representatives of various organizations relevant to the status of defacto segregation in the Chicago public schools. (NH) - U.S.-DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH, EDUCA-TION & -17/air- N- OFFICE OF EDUCATION C) DE FACTO SCHOOL SEGREGATION EXACTLY AS RECEIVEDFROM THE /*\, CUMENT HAS BEEN REPRODUCED CV)) It POINTS OF VIEWOR OPINIONSe OR ORGANIZATION ORIGINATING OFFICIAL OFFICE OF EDUrATION DO NOT NECESSARILY REPRESENT OR POLICY. HEARINGS BEFORE A SPECIAL SUBCOMMITTEE OF THE COMMITTEE ON EDUCATION AND LABOR HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES EIGHTY-NINTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION ON INVESTIGATION OP DE FACTO RACIAL SEGREGATION IN CHICAGO'S PUBLIC SCHOOLS HEARINGS BEL/3 IN WASHINGTON, D.C., JULY 27 AND 28, 1965 Printed for the use of the Committee on Education and Labor ADAM C. POWELL, Choinnos 640 U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 52-579 0 WASHINGTON : 1955 Office ofEducation-EEOP Researchand Materials Branch COMMITITE ON EDUCATION AND LABOR ADAM C. POWELL, New York, Chairman CARL D. PERKINS, Kentucky WILLIAM H. AYRES, Ohio EDITH GREEN, Oregon ROBERT P. GRIFFIN, Michigan JAMESEOOSEVELT, California ALBERT H. -

Two Societies

Two Societies (1965-1968) MARTIN LUTHER KING, JR: There is nothing more dangerous than to build a society with a large segment of people in that society who feel they have no stake in it, who feel like they have nothing to lose. People who have stake in their society protect that society, but when they don't have it, they unconsciously want to destroy it. NARRATOR: August, 1965, black residents in Watts, a Los Angeles neighborhood, took to streets in anger. The uprising lasted six days and left 34 people dead. Watts was a challenge to the nation and to the nonviolent philosophy of Martin Luther King. MAN: To Dr. King that we have here, I say this. Sure, we like to be nonviolent, but we up here in the Los Angeles area, will not turn the other cheek. NARRATOR: The civil rights movement King led had won a major victory days earlier when President Lyndon Johnson signed the Voting Rights Act. But outside the South, little had changed. Anger was building. It was time for King and his staff to move north. Their first target, Chicago, Illinois, the second largest city in America. A fourth of Chicago's residents were black. Despite a decade of protest and some successes, many faced profound poverty and discrimination. LINDA BRYANT-HALL: When I first heard that Dr. King was going to come to Chicago, I was elated. I said, "Oh my gosh, Chicago's going to get involved in all of this. You know, Dr. King has got a powerful following, a powerful message and he's going to bring it to Chicago to help with the movement here. -

The Chicago ‘Advance Team’: the Evolution of College Activists

ABSTRACT THE CHICAGO ‘ADVANCE TEAM’: THE EVOLUTION OF COLLEGE ACTIVISTS The tumultuous years of the 1960s evolved from the thaw of the Cold War era. College campuses’ emerging interest in the Civil Rights movement was exacerbated by the escalating violence within the Deep South. By the time events from Selma, Alabama reached the living rooms and college dorm rooms in the North, waves of activism had spread across the nation. This study follows a group of college activists who traveled south, quickly adapted to movement strategy, and forged lifetime friendships while working for Dr. Martin Luther King’s organization, the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC). Most of the core group stayed in the South in the summer of 1965 after completing non- violence training in Atlanta. Showing exemplary skills and leadership qualities, they would eventually form Rev. James Bevel’s ‘advance team’ within the Chicago Freedom Movement. This ‘elite’ unit fought their own battles against poverty, racism, and violence while in Chicago. Their story is one from below, and captures the heart and spirit of true activism, along with memories of music, rent strikes, a lead-poisoning campaign, and even a love affair, within the Chicago Freedom Movement in 1965-1966. Samuel J LoProto May 2016 THE CHICAGO ‘ADVANCE TEAM’: THE EVOLUTION OF COLLEGE ACTIVISTS by Samuel J LoProto A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in History in the College of Social Sciences California State University, Fresno May 2016 APPROVED For the Department of History: We, the undersigned, certify that the thesis of the following student meets the required standards of scholarship, format, and style of the university and the student's graduate degree program for the awarding of the master's degree. -

Page 1 Chicago Studies

- THE UNIVERSITY�5 OF CHICAGO Chicago Studies THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO Chicago Studies ���� –�5 William Hamilton Fernandez Melissa High Michael Finnin McCown Jaime Sánchez Jr. Erin M. Simpson Rachel Whaley MANAGING EDITOR Daniel J. Koehler THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO Chicago Studies ���� –�5 � Preface 8 Acknowledgments �� To Dissipate Prejudice Julius Rosenwald, the Evolution of Philanthropic Capital, and the Wabash YMCA William Hamilton Fernandez �� Creating Wartime Community The Work of Chicago Clubwomen during World War II Melissa High ��� Making Peace, Making Revolution Black Gangs in Chicago Politics, 1992–1993 Michael Finnin McCown ��� Contested Constituency Latino Politics and Pan-ethnic Identity Formation in the 1983 Chicago Mayoral Election of Harold Washington Jaime Sánchez Jr. �38 Digital Dividends Investigating the User Experience in Chicago’s Public Computer Center System Erin M. Simpson ��� Waste Not Schools as Agents of Pro-Environmental Behavior Change in Chicago Communities Rachel Whaley Chicago Studies © The University of Chicago 2017 1 CHICAGO STUDIES Preface The Chicago Studies Program works to join the College’s undergraduate curriculum with the dynamic world of praxis in our city. It encourages students to develop their courses of study in dialogue with our city through facilitating internships, service opportunities, and other kinds of engagement, and through academic offerings like the Chicago Studies Quarter, thesis workshops, and the provision of excursions for courses. TWe believe that this produces not only richer, more deeply informed academic work, but also more thoughtful, humanistic interaction with the city and its most pressing questions. A complete listing of opportuni- ties through Chicago Studies is available on the website: chicagostudies .uchicago.edu. -

Complete List of Contents

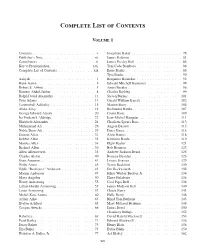

Complete List of Contents Volume 1 Contents. v Josephine Baker . 78 Publisher’s Note . vii James Baldwin. 81 Contributors . xi James Presley Ball. 84 Key to Pronunciation. xvii Toni Cade Bambara . 86 Complete List of Contents . xix Ernie Banks . 88 Tyra Banks. 90 Aaliyah . 1 Benjamin Banneker . 92 Hank Aaron . 3 Edward Mitchell Bannister . 94 Robert S. Abbott . 5 Amiri Baraka . 96 Kareem Abdul-Jabbar . 8 Charles Barkley . 99 Ralph David Abernathy . 11 Steven Barnes . 101 Faye Adams . 14 Gerald William Barrax . 102 Cannonball Adderley . 15 Marion Barry . 104 Alvin Ailey . 18 Richmond Barthé. 107 George Edward Alcorn . 20 Count Basie . 109 Ira Frederick Aldridge. 22 Jean-Michel Basquiat . 111 Elizabeth Alexander . 24 Charlotta Spears Bass . 113 Muhammad Ali . 26 Angela Bassett . 115 Noble Drew Ali . 29 Daisy Bates. 116 Damon Allen . 31 Alvin Batiste . 118 Debbie Allen . 33 Kathleen Battle. 119 Marcus Allen . 34 Elgin Baylor . 121 Richard Allen . 36 Bob Beamon . 123 Allen Allensworth . 38 Andrew Jackson Beard. 125 Charles Alston . 40 Romare Bearden . 126 Gene Ammons. 41 Louise Beavers . 129 Wally Amos . 43 Tyson Beckford . 130 Eddie “Rochester” Anderson . 45 Jim Beckwourth . 132 Marian Anderson . 47 Julius Wesley Becton, Jr. 134 Maya Angelou . 50 Harry Belafonte . 136 Henry Armstrong . 53 Cool Papa Bell . 138 Lillian Hardin Armstrong . 55 James Madison Bell . 140 Louis Armstrong . 57 Chuck Berry . 141 Molefi Kete Asante . 60 Halle Berry . 144 Arthur Ashe . 63 Blind Tom Bethune . 145 Evelyn Ashford . 65 Mary McLeod Bethune . 148 Crispus Attucks . 66 James Bevel . 150 Chauncey Billups . 152 Babyface. 69 David Harold Blackwell . 153 Pearl Bailey . 71 Edward Blackwell . -

Records of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, 1954–1970

A Guide to the Microfilm Edition of BLACK STUDIES RESEARCH SOURCES Microfilms from Major Archival and Manuscript Collections General Editors: John H. Bracey, Jr. and August Meier Records of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, 1954–1970 Part 4: Records of the Program Department Editorial Adviser Cynthia P. Lewis Project Coordinator Randolph H. Boehm Guide compiled by Blair Hydrick A microfilm project of UNIVERSITY PUBLICATIONS OF AMERICA An Imprint of CIS 4520 East-West Highway • Bethesda, MD 20814-3389 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Records of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, 1954–1970 [microform] / project coordinator, Randolph H. Boehm. microfilm reels. — (Black studies research sources) Accompanied by a printed guide, compiled by Blair D. Hydrick, entitled: A guide to the microfilm edition of Records of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, 1954–1970. Contents: pt. 1. Records of the President’s Office—[Etc.]— pt. 4. Records of the Program Department ISBN 1-55655-558-X (pt. 4 : microfilm) 1. Southern Christian Leadership Conference—Archives. 2. Afro- Americans—Civil rights—Southern States—History—Sources. 3. Civil rights movements—United States—History—20th century— Sources. 4. Southern States—Race relations—History—Sources. I. Boehm, Randolph. II. Hydrick, Blair. III. Southern Christian Leadership Conference. IV. University Publications of America (Firm) V. Title: Guide to the microfilm edition of Records of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, 1954–1970. VI. Series. [E185.61] 323.1’196073075—dc20 95-24346 CIP Copyright © 1995 by University Publications of America. All rights reserved. ISBN 1-55655-558-X. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction......................................................................................................... vii Scope and Content Note..................................................................................... -

The Chicago Freedom Movement and the Federal Fair Housing Act

NON-VIOLENT DIRECT ACTION AND THE LEGISLATIVE PROCESS: THE CHICAGO FREEDOM MOVEMENT AND THE FEDERAL FAIR HOUSING ACT LEONARD S. RUBINOWITZ* KATHRYN SHELTON** If out of [the Chicago Freedom Movement] came a fair housing bill, just as we got a public accommodations bill out of Birmingham and a right to vote out of Selma, the Chicago movement was a success, and a documented success. Jesse Jackson1 INTRODUCTION Fresh from the success of the 1965 Selma, Alabama, voting rights campaign and the passage of the landmark Voting Rights Act, Martin Luther King and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (“SCLC”) decided to take their Southern civil rights movement north to Chicago.2 Dr. King and the SCLC joined forces with local Chicago activists to launch the Chicago Freedom Movement (“CFM”).3 The Southern civil rights activists decided that the Movement needed to address racism and poverty in the urban North and selected Chicago as the first site of this new initiative. The objectives to be achieved and the strategies and tactics to be employed remained to be determined. By the middle of 1966, the CFM decided to target racial discrimination and segregation in Chicago’s housing market.4 That summer witnessed a direct action campaign aimed at white neighborhoods that excluded Blacks5—starting * Professor of Law, Northwestern University School of Law. ** Staff Attorney, Legal Assistance Foundation of Metropolitan Chicago. The Authors would like to thank Jonathan Entin and Florence Wagman Roisman for their extremely helpful comments. The Authors would also like to thank Sean Morales-Doyle for his invaluable contributions to this Article, Susanne Pringle, Alyssa Morin, Helena Lefkow, and Maria Barbosa for their excellent research assistance, and Tim Jacobs for his logistical assistance. -

High School Students' Movement for Quality Public Education, 1966-1971

CHICAGO HIGH SCHOOL STUDENTS' MOVEMENT FOR QUALITY PUBLIC EDUCATION, 1966-1971 by Dionne Danns' Through walkouts, boycotts, and sit-ins, black high school students in Chicago from the late 1960s until the early 1970s expressed their discontent over the inferior quaiity of public schooling they were receiving. Influenced by the school refonn activities begun in the early part of the decade, students issued demands and manifestos to their school administrators calling for black history courses, black teachers and administrators, improvements in the school facilities, reinstatement of dismissed teachers and suspended or expelled students, and community and student involvement in decision making within the schools. Students organized walkouts at individual schools, and joined together in October 1968 to conduct three citywide school boycotts in support of their demands for educational change. Even after some demands were met, students at various schools continued their protests into the 1970s. The historical literature on the Civil Rights Movement focuses on black students' role as participants and organizers of nonviolent direct action protests. The literature has also focused on black student activism on college campuses.! For the most part, high school activism has not been the subject of scholarly research. Wiliiam H. Chafe in Civilities and Civil Rights: Greensboro, North Carolina, and the Black Freedom Struggle, Clayborne Carson in In Struggle: SNCC and the Black AW<lkening of the 19605, and William H. Exum in Paradoxes of Protest: