ACTA HISTRIAE 25, 2017, 2, Pp

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Proceedings Vol. 1

Book of Proceedings EighthFifth InternationalInternational ConferenceConference on:on: “Education“Education andand SocialSocial Sciences-Sciences- ChallengesChallenges towardstowards thethe Future”Future” 20182018 (ICES(ICES VIII- V- 2018)2018) 15 DECEMBER 2018 Bialystok 10 MARCH - Poland 2018 Organized by International Institute for Private- Commercial- and Competition Law(IIPCCL) in Partnership with University of Białystok (Poland), Institut za naučna istraživanja (Montenegro), Institute of History and Political Science of the University of Białystok (Poland), Tirana Business University (Albania), University College Pjeter Budi of Pristina, (Kosovo) Edited by: Dr. Lena Hoff man 1 Eighth InternationalFifth International Conference on: Conference “Education on: and “Education Social Sciences- and Challenges Social Sciences- towardsChallenges the Future” towards 2018 the Future” 2018 (ICES(ICES VIII- V- 2018) 15 December 2018 Vienna, 8 April 2017 Editor:Editor: Dr. Lena Lena Ho Hoff manff man Endri Papajorgji Tirana ISBN: 978-9928-259-40-0 ISBN: 978-9928-259-05-9 Bialystok - Poland Disclaimer Every reasonable effort has been made to ensure that the material in this book is true, correct, complete, and appropriate at the time of writing. Nevertheless the publishers, the editors and the authors do not accept responsibility for any omission or error, or any injury, damage, loss or financial consequences arising from the use of the book. The views expressed by contributors do not necessarily reflect those of University of Bialystok (Poland), International Institute for Private, Commercial and Competition law, Institut za nau na istra ivanja (Montenegro), Tirana Business University (Albania) and University College Pjeter Budi of Pristina, (Kosovo). 22 2 International Scientific Committee ICBLAS III 2015 (ICES(ICES VII V-2018) 2018) Prof. -

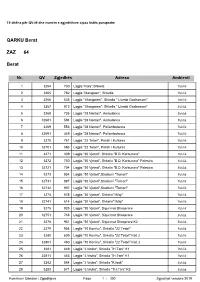

Crystal Reports

Të dhëna për QV-të dhe numrin e zgjedhësve sipas listës paraprake QARKU Berat ZAZ 64 Berat Nr. QV Zgjedhës Adresa Ambienti 1 3264 730 Lagjia "Kala",Shkolla Publik 2 3265 782 Lagjia "Mangalen", Shkolla Publik 3 3266 535 Lagjia " Mangalem", Shkolla " Llambi Goxhomani" Publik 4 3267 813 Lagjia " Mangalem", Shkolla " Llambi Goxhomani" Publik 5 3268 735 Lagjia "28 Nentori", Ambulanca Publik 6 32681 594 Lagjia "28 Nentori", Ambulanca Publik 7 3269 553 Lagjia "28 Nentori", Poliambulanca Publik 8 32691 449 Lagjia "28 Nentori", Poliambulanca Publik 9 3270 751 Lagjia "22 Tetori", Pallati I Kultures Publik 10 32701 593 Lagjia "22 Tetori", Pallati I Kultures Publik 11 3271 409 Lagjia "30 Vjetori", Shkolla "B.D. Karbunara" Publik 12 3272 750 Lagjia "30 Vjetori", Shkolla "B.D. Karbunara" Palestra Publik 13 32721 704 Lagjia "30 Vjetori", Shkolla "B.D. Karbunara" Palestra Publik 14 3273 854 Lagjia "30 Vjetori",Stadiumi "Tomori" Publik 15 32731 887 Lagjia "30 Vjetori",Stadiumi "Tomori" Publik 16 32732 907 Lagjia "30 Vjetori",Stadiumi "Tomori" Publik 17 3274 578 Lagjia "30 Vjetori", Shkolla"1Maji" Publik 18 32741 614 Lagjia "30 Vjetori", Shkolla"1Maji" Publik 19 3275 925 Lagjia "30 Vjetori", Sigurimet Shoqerore Publik 20 32751 748 Lagjia "30 Vjetori", Sigurimet Shoqerore Publik 21 3276 951 Lagjia "30 Vjetori", Sigurimet Shoqerore K2 Publik 22 3279 954 Lagjia "10 Korriku", Shkolla "22 Tetori" Publik 23 3280 509 Lagjia "10 Korriku", Shkolla "22 Tetori" Kati 2 Publik 24 32801 450 Lagjia "10 Korriku", Shkolla "22 Tetori" Kati 2 Publik 25 3281 649 Lagjia "J.Vruho", -

SEA of Montenegro's National Climate Change Strategy

The European Union’s IPA Programme for Montenegro SEA of Montenegro’s National Climate Change Strategy (NCCS) EuropeAid/127054/C/SER/multi SEA Report Prepared by: Juan Palerm, Jiří Dusík, Ivana Šarić, Gordan Golja and Marko Slokar Ref. Contract N° 2014/354504 Final Report 14 September, 2015 Development of the Strategic Environment Assessment (SEA) for the Project Title: National Climate Change Strategy by 2030 (EuropeAid/127054/C/SER/multi) Financing: IPA Reference No: (EuropeAid/127054/C/SER/multi) Starting Date: February 2015 End Date (Duration): June 2015 Contract Number: 2014/354504 Contracting Authority: Delegation of the European Union to Montenegro Task Manager: Mr. Sladjan MASLAĆ, Task Manager Address: Vuka Karadžića 12, 81000 Podgorica Phone: + 382 (0) 20 444 600 Fax: + 382 (0) 20 444 666 E-mail: [email protected] Beneficiary: Ministry of Sustainable Development and Tourism [MSDT] Head of PSC: Ivana VOJINOVIC Address: IV Proleterske brigade 19, 81000 Podgorica Phone: + 382 (0) 20 446 208 Fax: + 382 (0) 20 446 215 E-mail: [email protected] Contractor: Particip GmbH Address: Merzhauser Str. 183, D - 79100 Freiburg, Germany Phone: +49 761 79074 0 Fax: +49 761 79074 90 Project Director: Martin GAYER E-mail address: [email protected] Date of report: 27/03/2015 Revision NA Author of the report: Juan PALERM .............................................. Controlled by: Martin GAYER .............................................. Approved: Mr. Siniša STANKOVIĆ [Head PSC] .............................................. Approved: Mr. Slađan MASLAĆ [Task Manager of EUD] .............................................. Disclaimer: The opinions expressed in this Report are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the opinions of the EU Delegation or any other organisation mentioned in the report. -

Europe Report, Nr. 153: Pan-Albanianism

PAN-ALBANIANISM: HOW BIG A THREAT TO BALKAN STABILITY? 25 February 2004 Europe Report N°153 Tirana/Brussels TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY AND RECOMMENDATIONS................................................. i I. INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................................... 1 A. THE BURDENS OF HISTORY...................................................................................................2 B. AFTER THE FALL: CHAOS AND NEW ASPIRATIONS................................................................4 II. THE RISE AND FALL OF THE ANA......................................................................... 7 III. ALBANIA: THE VIEW FROM TIRANA.................................................................. 11 IV. KOSOVO: INTERNAL DIVISIONS ......................................................................... 14 V. MACEDONIA: SHOULD WE STAY OR SHOULD WE GO? ............................... 17 VI. MONTENEGRO, SOUTHERN SERBIA AND GREECE....................................... 20 A. ALL QUIET ON THE WESTERN FRONT?................................................................................20 B. THE PRESEVO VALLEY IN SOUTHERN SERBIA....................................................................22 C. THE GREEK QUESTION........................................................................................................24 VII. EMIGRES, IDENTITY AND THE POWER OF DEMOGRAPHICS ................... 25 A. THE DIASPORA: POLITICS AND CRIME.................................................................................25 -

Anel NOVO 18.06.08 Sadrzaj:Layout 1.Qxd

Dr. Mustafa Memić GUSINJSKO-PLAVSKA KRAJINA U VRTLOGU HISTORIJE Sarajevo, 2008. IZDAVAČ: Institut za istraživanje zločina protiv čovječnosti i međunarodnog prava Univerziteta u Sarajevu ZA IZDAVAČA: prof. dr. Smail Čekić UREDNICI: dr. Safet Bandžović prof. mr. Muharem Kreso RECENZENTI: akademik Muhamed Filipović mr. Sefer Halilović LEKTOR: Sadžida Džuvić KORICE: Dževdet Nikočević DTP: Anel Ćuhara ŠTAMPARIJA: AMOS GRAF d.o.o. TIRAŽ: 500 PREDGOVOR Ovom knjigom želim objasniti neke od burnih događaja u mom rodnom kraju koji su bitno utjecali na formiranje nacionalne svijesti mojih sunarodnika i na njihov ekonomski i društveno-politički položaj poslije Drugog svjetskog rata. U narodu moga kraja duboko su urezana dva događaja. Jedan je osvajanje Gusinjsko-plavskog kraja od crnogorske vojske 1912, a drugi se odnosi na razdoblje od 1919. do 1945. Njima se objašnjava dolazak jednog puka srpske vojske, koji je poslije proboja Solunskog fronta nastupao vardarskom dolinom i od Skoplja i Kosovske Mitrovice uputio se prema Crnoj Gori. Pritom se prema Podgorici kretao preko Gusinjsko-plavske krajine, nakon čega je došlo do pobune Bošnjaka i Albanaca, te pokušaja uspostavljanja nove vlasti, a zatim do formiranja dviju vasojevićkih brigada - Donja i Gornja vasojevićka - koje su se kao paravojne jedinice pridružile srpskoj vojsci i djelovale pod rukovodstvom centralne Crnogorske uprave u Podgorici. Tom su prilikom u Plavu i Gusinju formirane i dvije vojne jedinice - dva bataljona - najprije kao komitske jedinice, koje su u početku djelovale u sastavu komitskog pokreta u Crnoj Gori. Strahovalo se da se uspostavljanjem njihove vlasti ne nametnu policijske vlasti, koje su tokom 1912-1913. počinile teške zločine (masovno strijeljanje – prema nekim podacima ubijeno je preko 8.000 Bošnjaka i Albanaca, a došlo je i do nasilnog pokrštavanja oko 12.500 ljudi). -

Recherches Research Studies

Balkanologie VI [1-2], décembre 2002 \ 75 RECHERCHES RESEARCH STUDIES Balkanologie VI [1-2], décembre 2002, p. 77-100 \ 77 MOUNTAINS AS « LIEUX DE MÉMOIRE » HIGHLAND VALUES AND NATION-BUILDING IN THE BALKANS1 Ulf Brunnbauer and Robert Pichler* INTRODUCTION Notions about shared history and the self-ascription of specific cultural and moral values are constitutive for the formation of nations and their conti nuity. While this is a common sense assumption, proven by extensive research also for the case of Southeast European nations, the spatial dimension of col lective commemoration and of the construction of national identities have been much less considered. As Pierre Nora and his collaborators have shown, modern nation states require “places” onto which they can pin historical com memoration and imagination (lieux de mémoire). In the course of modernisa tion collective memory lost its organic nature and is no longer reproduced au tomatically. Collective memory is not any more transmitted orally from one generation to the other but rather has become the endeavour of professional memory-makers such as historians and intellectuals2. In order to be compre hensible and meaningful to people, nationally significant historical events must be anchored in popular experience and consciousness. In this operation, locations and material items as well as rituals and other features of culture be 1 This paper results from our research project “Ecology, Organisation of Labour, and Family Forms in the Balkans. Mountain societies compared” which was funded by the Austrian Science Fund (FWF) and car ried out at the Department of Southeast European History at the University of Graz between 1998 and 2001. -

English and INTRODACTION

CHANGES AND CONTINUITY IN EVERYDAY LIFE IN ALBANIA, BULGARIA AND MACEDONIA 1945-2000 UNDERSTANDING A SHARED PAST LEARNING FOR THE FUTURE 1 This Teacher Resource Book has been published in the framework of the Stability Pact for South East Europe CONTENTS with financial support from the Dutch Ministry of Foreign Affairs. It is available in Albanian, Bulgarian, English and INTRODACTION..............................................3 Macedonian language. POLITICAL LIFE...........................................17 CONSTITUTION.....................................................20 Title: Changes and Continuity in everyday life in Albania, ELECTIONS...........................................................39 Bulgaria and Macedonia POLITICAL PERSONS..............................................50 HUMAN RIGHTS....................................................65 Author’s team: Terms.................................................................91 ALBANIA: Chronology........................................................92 Adrian Papajani, Fatmiroshe Xhemali (coordinators), Agron Nishku, Bedri Kola, Liljana Guga, Marie Brozi. Biographies........................................................96 BULGARIA: Bibliography.......................................................98 Rumyana Kusheva, Milena Platnikova (coordinators), Teaching approches..........................................101 Bistra Stoimenova, Tatyana Tzvetkova,Violeta Stoycheva. ECONOMIC LIFE........................................103 MACEDONIA: CHANGES IN PROPERTY.......................................104 -

Print This Article

E-ISSN 2281-4612 Academic Journal of Interdisciplinary Studies Vol 5 No 3 S1 ISSN 2281-3993 MCSER Publishing, Rome-Italy December 2016 Teachers Civic Education and Their Methodological Skills Affect Student Engagement in Civic Participation Dr. Lindita Lutaj University "Aleksander Moisiu", Faculty of Education, Department of Pedagogy, Albania Email: [email protected] Doi:10.5901/ajis.2016.v5n3s1p336 Abstract Civic education is important, because the society needs people to contribute in the most effective way. The teacher plays an important role in encouraging pupils to civic actions. The aim of this study is find out the relationship between teachers civic education and their methodological skills in students civic participation. The statistical package of social sciences (SPSS 20) was used for data analysis. Questionnaires were administered to 34 teachers who give social education subject in 6th-9th grade and 414 students of these teachers, in Durres and Elbasan. The factorial analysis of the questionnaire on teachers civic education discovered two important factors: civic responsibility and civic values, while according to teachers’ methodological skills discovered three factors: the quality of the class, learning and student assessment. It was also observed that there is a positive relationship between teachers’ civic education and their methodological skills with students’ civic participation, which it was reported by teachers or perceived by students. There is a significant statistical relationship between teachers civic education and students civic participation: r = .40 (p <0:01), which is stronger than teachers methodological skills and students civic participation: r = .28 (p <0:01). According to the findings of this study should be increased teachers training programs at local and national level. -

The Strategic Action Plan (Sap) for Skadar/Shkodra Lake Albania & Montenegro

Ministry of Tourism and Environment of Montenegro (MoTE) Ministry of Environment, Forests and Water Administration of Albania (MEFWA) LAKE SKADAR/SHKODRA INTEGRATED ECOSYSTEM MANAGEMENT PROJECT THE STRATEGIC ACTION PLAN (SAP) FOR SKADAR/SHKODRA LAKE ALBANIA & MONTENEGRO Prepared by: Association for Protection of Aquatic Wildlife of Albania (APAWA) Center for Ecotoxicological Research of Montenegro (CETI) In cooperation with: SNV Montenegro ______ Global Environment Facility (GEF) World Bank (WB) April 2007 SAP for Skadar/Shkodra Lake – Albania & Montenegro 2007 Working group for the preparation of SAP: Albania Montenegro Sajmir Beqiraj (APAWA) Ana Mišurović (CETI) Genti Kromidha (APAWA) Danjiela Šuković (CETI) Luan Dervishej (APAWA) Andrej Perović (University of Montenegro) Dritan Dhora (APAWA) Zoran Mrdak (National Park of Skadar Lake) Agim Shimaj (LSIEMP) Prof Aleksandar Ćorović (University of Montenegro) Zamir Dedej (MEFWA) Viktor Subotić (MoTE) Experts of SNV Montenegro Jan Vloet Martin Schneider–Jacoby Alexander Mihaylov Zvonko Brnjas 2 SAP for Skadar/Shkodra Lake – Albania & Montenegro 2007 ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS ALB Albania APAWA Association for Protection of the Aquatic Wildlife of Albania BSAP Biodiversity Strategy and Action Plan CETI Center for Ecotoxicological Research of Montenegro COOPI Cooperazione Internazionale COSPE Cooperation for the Development of Emergent Countries CSDC Civil Society Development Centre CTR Council of Territorial Regulation EU European Union FMO Fishing Management Organization GEF Global Environment -

The Genetic Structure of the Population of the Koplik Municipality Calculated by the Isonomy

Journal of Natural Sciences Research www.iiste.org ISSN 2224-3186 (Paper) ISSN 2225-0921 (Online) Vol.4, No.10, 2014 The Genetic Structure of the Population of the Koplik Municipality Calculated by the Isonomy Ermira Hoxhaj ¹* Zyri Bajrami ¹·² ¹ Departament of Biology – Chemistry,University of Shkodra,Shkodra,Albania. *E-mail:[email protected] ² Departament of Biology,Universiyt of Tirana,Bulevardi Zogu I,Tirana,Albania E-mail:[email protected] Abstract The main focus of this study is the human population of the Municipality of Koplik,in Albania. The city of Koplik is situated 17 km at the North of Shkodra city,in Albania. The genetic structure and connections among the inhabitants of Koplik, have been studied according to the distribution of the surnames of 18831 individuals, identified by 652 surnames, which resulted from the compilation of the genealogical trees.The coefficient of kinship was calculated, because of the isonomy of the case, along with evaluations of the α of Fisher as indicator of the surname variety, evaluations of Fst inbreeding coefficients and evaluations of the Karlin-McGregor`s coefficient. The surname distribution has been calculated based on the logarithm of the surname number and the number of the times such surname is identified. All these parameters have been calculated by means of the data extracted from the genealogical trees in three different methods, based on the surnames inherited from the father, from the mother and a another one, based on casual distribution of the surnames of the same persons,but without considering the genealogical relationship.All these methods show a high value of kinship, but when the three methods are compared, the results have obvious differences. -

The Differential Impact of War and Trauma on Kosovar Albanian Women Living in Post-War Kosova

The Differential Impact of War and Trauma on Kosovar Albanian Women Living in Post-War Kosova Hanna Kienzler Department of Anthropology McGill University, Montreal June 2010 A thesis submitted to McGill University in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy © 2010 Hanna Kienzler Abstract The war in Kosova had a profound impact on the lives of the civilian population and was a major cause of material destruction, disintegration of social fabrics and ill health. Throughout 1998 and 1999, the number of killings is estimated to be 10,000 with the majority of the victims being Kosovar Albanian killed by Serbian forces. An additional 863,000 civilians sought or were forced into refuge outside Kosova and 590,000 were internally displaced. Moreover, rape and torture, looting, pillaging and extortion were committed. The aim of my dissertation is to rewrite aspects of the recent belligerent history of Kosova with a focus on how history is created and transformed through bodily expressions of distress. The ethnographic study was conducted in two Kosovar villages that were hit especially hard during the war. In both villages, my research was based on participant observation which allowed me to immerse myself in Kosovar culture and the daily activities of the people under study. The dissertation is divided into four interrelated parts.The first part is based on published accounts describing how various external power regimes affected local Kosovar culture, and how the latter was continuously transformed by the local population throughout history. The second part focuses on collective memories and explores how villagers construct their community‟s past in order to give meaning to their everyday lives in a time of political and economic upheaval. -

Behind Stone Walls

BEHIND STONE WALLS CHANGING HOUSEHOLD ORGANIZATION AMONG THE ALBANIANS OF KOSOVA by Berit Backer Edited by Robert Elsie and Antonia Young, with an introduction and photographs by Ann Christine Eek Dukagjini Balkan Books, Peja 2003 1 This book is dedicated to Hajria, Miradia, Mirusha and Rabia – girls who shocked the village by going to school. 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Preface Berita - the Norwegian Friend of the Albanians, by Ann Christine Eek BEHIND STONE WALLS Acknowledgement 1. INTRODUCTION Family and household Family – types, stages, forms Demographic processes in Isniq Fieldwork Data collection 2. ISNIQ: A VILLAGE AND ITS FAMILIES Once upon a time Going to Isniq Kosova First impressions Education Sources of income and professions Traditional adaptation The household: distribution in space Household organization Household structure Positions in the household The household as an economic unit 3. CONJECTURING ABOUT AN ETHNOGRAPHIC PAST Ashtu është ligji – such are the rules The so-called Albanian tribal society The fis The bajrak Economic conditions Land, labour and surplus in Isniq The political economy of the patriarchal family or the patriarchal mode of reproduction 3 4. RELATIONS OF BLOOD, MILK AND PARTY MEMBERSHIP The traditional social structure: blood The branch of milk – the female negative of male positive structure Crossing family boundaries – male and female interaction Dajet - mother’s brother in Kosova The formal political organization Pleqësia again Division of power between partia and pleqësia The patriarchal triangle 5. A LOAF ONCE BROKEN CANNOT BE PUT TOGETHER The process of the split Reactions to division in the family Love and marriage The phenomenon of Sworn Virgins and the future of sex roles Glossary of Albanian terms used in this book Bibliography Photos by Ann Christine Eek 4 PREFACE ‘Behind Stone Walls’ is a sociological, or more specifically, a social anthropological study of traditional Albanian society.