50 Klys the Third Reich's Pean.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Analysis of Media Stereotypes of the Russian Image in Media Studies in the Student Audience (Example: the Screen Versions of Jules Verne's Novel “Michael Strogoff”)

European Researcher, 2014, Vol.(83), № 9-2 Copyright © 2014 by Academic Publishing House Researcher Published in the Russian Federation European Researcher Has been issued since 2010. ISSN 2219-8229 E-ISSN 2224-0136 Vol. 83, No. 9-2, pp. 1718-1724, 2014 DOI: 10.13187/er.2014.83.1718 www.erjournal.ru Cultural studies Культурологические науки Analysis of Media Stereotypes of the Russian Image in Media Studies in the Student Audience (example: the screen versions of Jules Verne's Novel “Michael Strogoff”) Alexander Fedorov Anton Chekhov Taganrog Institute (branch of Rostov State University of Economics), Russian Federation Dr. (Pedagogy), Professor E-mail: [email protected] Abstract As a result of the analysis students come to the conclusion that the screen adaptations of Jules Verne's novel ''Michael Strogoff'' create, though an oversimplified and adapted to western stereotypes of perception, but a positive image of Russia – as a stronghold of European values at the Asian frontiers, a country with a severe climate, boundless Siberian spacious areas, manly and patriotic warriors, a wise monarchy. At the same time, both Jules Verne's novel and its screen adaptations contain clear-cut western pragmatism – the confidence that if a man has a proper will he can rule his destiny. Keywords: media stereotypes; Russian image; media studies; media literacy education; film studies; students; screen; film; Michael Strogoff. Introduction The last bright Cold War movie peak fell on the early 1980s when Russians as part of the monolithic and aggressive system were portrayed as products of their environment – malicious, potent, highly revolutionary in the whole world. -

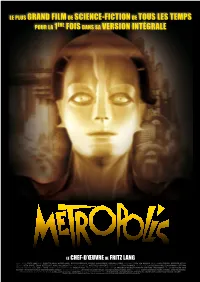

Dp-Metropolis-Version-Longue.Pdf

LE PLUS GRAND FILM DE SCIENCE-FICTION DE TOUS LES TEMPS POUR LA 1ÈRE FOIS DANS SA VERSION INTÉGRALE LE CHEf-d’œuvrE DE FRITZ LANG UN FILM DE FRITZ LANG AVEC BRIGITTE HELM, ALFRED ABEL, GUSTAV FRÖHLICH, RUDOLF KLEIN-ROGGE, HEINRICH GORGE SCÉNARIO THEA VON HARBOU PHOTO KARL FREUND, GÜNTHER RITTAU DÉCORS OTTO HUNTE, ERICH KETTELHUT, KARL VOLLBRECHT MUSIQUE ORIGINALE GOTTFRIED HUPPERTZ PRODUIT PAR ERICH POMMER. UN FILM DE LA FRIEDRICH-WILHELM-MURNAU-STIFTUNG EN COOPÉRATION AVEC ZDF ET ARTE. VENTES INTERNATIONALES TRANSIT FILM. RESTAURATION EFFECTUÉE PAR LA FRIEDRICH-WILHELM-MURNAU-STIFTUNG, WIESBADEN AVEC LA DEUTSCHE KINE MATHEK – MUSEUM FÜR FILM UND FERNSEHEN, BERLIN EN COOPÉRATION AVEC LE MUSEO DEL CINE PABLO C. DUCROS HICKEN, BUENOS AIRES. ÉDITORIAL MARTIN KOERBER, FRANK STROBEL, ANKE WILKENING. RESTAURATION DIGITAle de l’imAGE ALPHA-OMEGA DIGITAL, MÜNCHEN. MUSIQUE INTERPRÉTÉE PAR LE RUNDFUNK-SINFONIEORCHESTER BERLIN. ORCHESTRE CONDUIT PAR FRANK STROBEL. © METROPOLIS, FRITZ LANG, 1927 © FRIEDRICH-WILHELM-MURNAU-STIFTUNG / SCULPTURE DU ROBOT MARIA PAR WALTER SCHULZE-MITTENDORFF © BERTINA SCHULZE-MITTENDORFF MK2 et TRANSIT FILMS présentent LE CHEF-D’œuvre DE FRITZ LANG LE PLUS GRAND FILM DE SCIENCE-FICTION DE TOUS LES TEMPS POUR LA PREMIERE FOIS DANS SA VERSION INTEGRALE Inscrit au registre Mémoire du Monde de l’Unesco 150 minutes (durée d’origine) - format 1.37 - son Dolby SR - noir et blanc - Allemagne - 1927 SORTIE EN SALLES LE 19 OCTOBRE 2011 Distribution Presse MK2 Diffusion Monica Donati et Anne-Charlotte Gilard 55 rue Traversière 55 rue Traversière 75012 Paris 75012 Paris [email protected] [email protected] Tél. : 01 44 67 30 80 Tél. -

Close-Up on the Robot of Metropolis, Fritz Lang, 1926

Close-up on the robot of Metropolis, Fritz Lang, 1926 The robot of Metropolis The Cinémathèque's robot - Description This sculpture, exhibited in the museum of the Cinémathèque française, is a copy of the famous robot from Fritz Lang's film Metropolis, which has since disappeared. It was commissioned from Walter Schulze-Mittendorff, the sculptor of the original robot, in 1970. Presented in walking position on a wooden pedestal, the robot measures 181 x 58 x 50 cm. The artist used a mannequin as the basic support 1, sculpting the shape by sawing and reworking certain parts with wood putty. He next covered it with 'plates of a relatively flexible material (certainly cardboard) attached by nails or glue. Then, small wooden cubes, balls and strips were applied, as well as metal elements: a plate cut out for the ribcage and small springs.’2 To finish, he covered the whole with silver paint. - The automaton: costume or sculpture? The robot in the film was not an automaton but actress Brigitte Helm, wearing a costume made up of rigid pieces that she put on like parts of a suit of armour. For the reproduction, Walter Schulze-Mittendorff preferred making a rigid sculpture that would be more resistant to the risks of damage. He worked solely from memory and with photos from the film as he had made no sketches or drawings of the robot during its creation in 1926. 3 Not having to take into account the morphology or space necessary for the actress's movements, the sculptor gave the new robot a more slender figure: the head, pelvis, hips and arms are thinner than those of the original. -

Film Front Weimar: Representations of the First World War in German Films from the Weimar Period (1919-1933) Kester, Bernadette

www.ssoar.info Film Front Weimar: Representations of the First World War in German Films from the Weimar Period (1919-1933) Kester, Bernadette Veröffentlichungsversion / Published Version Monographie / monograph Zur Verfügung gestellt in Kooperation mit / provided in cooperation with: OAPEN (Open Access Publishing in European Networks) Empfohlene Zitierung / Suggested Citation: Kester, B. (2002). Film Front Weimar: Representations of the First World War in German Films from the Weimar Period (1919-1933). (Film Culture in Transition). Amsterdam: Amsterdam Univ. Press. https://nbn-resolving.org/ urn:nbn:de:0168-ssoar-317059 Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Dieser Text wird unter einer CC BY-NC-ND Lizenz This document is made available under a CC BY-NC-ND Licence (Namensnennung-Nicht-kommerziell-Keine Bearbeitung) zur (Attribution-Non Comercial-NoDerivatives). For more Information Verfügung gestellt. Nähere Auskünfte zu den CC-Lizenzen finden see: Sie hier: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/deed.de * pb ‘Film Front Weimar’ 30-10-2002 14:10 Pagina 1 The Weimar Republic is widely regarded as a pre- cursor to the Nazi era and as a period in which jazz, achitecture and expressionist films all contributed to FILM FRONT WEIMAR BERNADETTE KESTER a cultural flourishing. The so-called Golden Twenties FFILMILM FILM however was also a decade in which Germany had to deal with the aftermath of the First World War. Film CULTURE CULTURE Front Weimar shows how Germany tried to reconcile IN TRANSITION IN TRANSITION the horrendous experiences of the war through the war films made between 1919 and 1933. -

Guides to German Records Microfilmed at Alexandria, Va

GUIDES TO GERMAN RECORDS MICROFILMED AT ALEXANDRIA, VA. No. 32. Records of the Reich Leader of the SS and Chief of the German Police (Part I) The National Archives National Archives and Records Service General Services Administration Washington: 1961 This finding aid has been prepared by the National Archives as part of its program of facilitating the use of records in its custody. The microfilm described in this guide may be consulted at the National Archives, where it is identified as RG 242, Microfilm Publication T175. To order microfilm, write to the Publications Sales Branch (NEPS), National Archives and Records Service (GSA), Washington, DC 20408. Some of the papers reproduced on the microfilm referred to in this and other guides of the same series may have been of private origin. The fact of their seizure is not believed to divest their original owners of any literary property rights in them. Anyone, therefore, who publishes them in whole or in part without permission of their authors may be held liable for infringement of such literary property rights. Library of Congress Catalog Card No. 58-9982 AMERICA! HISTORICAL ASSOCIATION COMMITTEE fOR THE STUDY OP WAR DOCUMENTS GUIDES TO GERMAN RECOBDS MICROFILMED AT ALEXAM)RIA, VA. No* 32» Records of the Reich Leader of the SS aad Chief of the German Police (HeiehsMhrer SS und Chef der Deutschen Polizei) 1) THE AMERICAN HISTORICAL ASSOCIATION (AHA) COMMITTEE FOR THE STUDY OF WAE DOCUMENTS GUIDES TO GERMAN RECORDS MICROFILMED AT ALEXANDRIA, VA* This is part of a series of Guides prepared -

Ein Film Um Mozart

Ein Film um Mozart Autor(en): Betschon, Alfred Objekttyp: Article Zeitschrift: Schweizer Film = Film Suisse : offizielles Organ des Schweiz. Lichtspieltheater-Verbandes, deutsche und italienische Schweiz Band (Jahr): 8 (1943) Heft 117 PDF erstellt am: 01.10.2021 Persistenter Link: http://doi.org/10.5169/seals-733400 Nutzungsbedingungen Die ETH-Bibliothek ist Anbieterin der digitalisierten Zeitschriften. Sie besitzt keine Urheberrechte an den Inhalten der Zeitschriften. Die Rechte liegen in der Regel bei den Herausgebern. Die auf der Plattform e-periodica veröffentlichten Dokumente stehen für nicht-kommerzielle Zwecke in Lehre und Forschung sowie für die private Nutzung frei zur Verfügung. Einzelne Dateien oder Ausdrucke aus diesem Angebot können zusammen mit diesen Nutzungsbedingungen und den korrekten Herkunftsbezeichnungen weitergegeben werden. Das Veröffentlichen von Bildern in Print- und Online-Publikationen ist nur mit vorheriger Genehmigung der Rechteinhaber erlaubt. Die systematische Speicherung von Teilen des elektronischen Angebots auf anderen Servern bedarf ebenfalls des schriftlichen Einverständnisses der Rechteinhaber. Haftungsausschluss Alle Angaben erfolgen ohne Gewähr für Vollständigkeit oder Richtigkeit. Es wird keine Haftung übernommen für Schäden durch die Verwendung von Informationen aus diesem Online-Angebot oder durch das Fehlen von Informationen. Dies gilt auch für Inhalte Dritter, die über dieses Angebot zugänglich sind. Ein Dienst der ETH-Bibliothek ETH Zürich, Rämistrasse 101, 8092 Zürich, Schweiz, www.library.ethz.ch http://www.e-periodica.ch Meyendorff mit. Die Aufnahmen in Babels- So kehrt Prof. Karl Ritter, der Regisseur zarte Innigkeit MozarFscher Musik mag in berg stehen kurz vor dem Abschluß. des Ufa-Filmes «Besatzung Dora», dieser uns ein Bild von Mozart formen, das in Hingegen befindet sich das zweite Harlan- Tage aus dem Süden zurück, wo er zum starkem Kontrast zu dem Mozart steht, Farbenprojekt noch mitten in der Teil selbst in Nordafrika Szenen des Filmes dessen Leben uns Regisseur Karl Hartl in Dreharbeit. -

The Holocaust: Historical, Literary, and Cinematic Y, Timeline

The Holocaust: Historical, Literary, and Cinematic Timeline (Note: Books and films are cited in the following formats: Books: Authorr, Tittle; Films: Tittle (Director, Country). For non-English language texts in all cases the standard English title has been used.) 1933 Januarry 30: Nazistake power March 9: concentration camp established at Dachau, outside Munich Appril1: state-sponsored boycott of Jewish shops and businesses 1935 May 21: Jews forbidden to serve in the German armed forces Septtember 15: promulgation of Nuremberg Laws 1936 June 17: Reichsführer SS Heinrich Himmler appointed head of all German police and security services 1938 March 12: Anschluss [union] of Austria; Austrian Jews immediately deprived of civil rights, subjected to Nazi race laws; by Septemberr, all Viennese Jewish busineses (33,000 in March) liquidated May: concentration camp established in the granite quarries at Mauthausen, near Linz (Hitler’s birthplace) June 9: main synagogue in Munich burnt down by Nazi stormtroopers Julyy–September: Jews forbidden to practice law or medicine October 6: Italy enacts anti-Semitic racial laws; 27: 18,000 Polish- born Jews deported to Poland November 10: Kristallnachtt; 191 synagogues fired; 91 Jews murdered; over 30,000 arrested; 20% of all Jewish property levied confiscated to paay for damage; 12: Göring orders the liquidation of all Jewish businesses by year’s end; 15: Jewish children banned from German schools December: no Jewish-owned businesses (of over 6,000 in 1933) remain in Berlin (Kathrine) Kressmann Taylor’s ‘Address Unknown’, published in Storry Magazine 1939 Januarry 30: in his annual speech commemorating the Nazi seizure of power, Hitler predicts that a new world war will result in “the annihilation of the Jewish race in Europe” March 15: Partition of Czechoslovakia: 118,000 more Jews fall under German dominion September 1: Germany invades Poland (Jewish population in 1939: approx. -

The Cruiser Blücher – 9Th of April 1940 Alf R. Jacobsen DISCLAIMER

The Cruiser Blücher – 9th of april 1940 Alf R. Jacobsen DISCLAIMER: This is a non-professional translation, done purely for the love of the subject matter. Some strange wording is to be expected, since sentence structure is not always alike in English or Norwegian. I'm also not a military nut after 1500, so some officer ranks, division names and the like may be different than expected because of my perhaps too-literal translation. Any notes of my own will be marked in red. I will drop the foreword, since it probably is of little interest to anyone but Norwegians. I’ll probably bother to translate it if requested at a later time. NOTE: This is the first book in a series of four – The cruiser Blücher(9th of april 1940), the King’s choice (10th of april 1940), Attack at dawn – Narvik 9-10th of april 1940 and Bitter victory – Narvik, 10th of april – 10th of june 1940. I might do more of these if I get the time and there is interest. PROLOGUE Visst Fanden skal der skytes med skarpt! -By the Devil, we will open fire! Oscarsborg, 9th of april 1940 03.58 hours The messenger came running just before 4 o'clock. He was sent by the communications officer with a sharp telephonic request from the main torpedo battery’s central aiming tower on Nordre Kaholmen islet, 500 meters away. The essence was later formulated by the battery commander, Andreas Andersen, in the following manner: «I asked for an absolute order if the approaching vessels were to be torpedoed.» If there is one moment in a human life that stands out truer than the rest, fortress commander Birger Eriksen had his at Oscarsborg this cold spring morning. -

Goebbels' Ufa: „Filmschaffen“ Und Ökonomie Elitenbildung Und Unterhaltungsproduktion

Symposium Linientreu und populär. Das Ufa-Imperium 1933 bis 1945 11. und 12. Mai, Filmreihe 11. bis 14. Mai 2017 Symposium Linientreu und populär. Das Ufa-Imperium 1933 bis 1945 Ablauf, Abstracts, Kurzbiografien, Filmreihe Do, 11.05., 13:00 Akkreditierung der Symposiumsteilnehmer*innen Deutsche Kinemathek – Museum für Film und Fernsehen im Filmhaus am Potsdamer Platz, Potsdamer Straße 2, 10785 Berlin, Veranstaltungsraum, 4. OG 14:00 Begrüßung: Rainer Rother (Künstlerischer Direktor, Deutsche Kinemathek), Wolf Bauer (Co-CEO UFA GmbH), Ernst Szebedits (Vorstand Friedrich-Wilhelm-Murnau- Stiftung) 14:30 Block 1 | 100 Jahre Ufa: Rückblicke und Ausblicke Die Ufa im Nationalsozialismus – Die ersten Jahre | Rainer Rother 15:00 Alfred Hugenberg: Wegbereiter der Ufa unterm Hakenkreuz? | Friedemann Beyer 15:30 Zwischen Tradition und Moderne. Zum NS-Kulturfilm 1933–1945 | Kay Hoffmann 16:00 Über die Popularität der Ufa-Filme, 1933–1945. Präsentation von Forschungs- ergebnissen des DFG-Projektes „Begeisterte Zuschauer: Über die Filmpräferenzen der Deutschen im Dritten Reich“ | Joseph Garncarz 16:30 Kaffeepause 17:00 Im Gespräch: Mediale Vermittlung von Zeitgeschichte. Zum Umgang mit brisanten historischen Stoffen | Teilnehmer: Nico Hofmann, Thomas Weber, Moderation: Klaudia Wick 18:00 Zwangsarbeit bei der Ufa | Almuth Püschel 18:30 Die Erinnerungen Piet Reijnens – ein niederländischer Zwangsarbeiter bei der Ufa | Jens Westemeier Ende ca. 19:00 Fr. 12.05., 9:30 Block 2 | Goebbels' Ufa: „Filmschaffen“ und Ökonomie Elitenbildung und Unterhaltungsproduktion. Ufa-Lehrschau und Deutsche Filmakademie als geistiger Ausdruck der Filmstadt Babelsberg im Nationalsozialismus | Rolf Aurich 10:00 Das große Scheitern: Die Ufa als Wirtschaftsunternehmen | Alfred Reckendrees 10:30 Mythos „Filmstadt Babelsberg“. Zur Baugeschichte der legendären Ufa-Filmfabrik | Brigitte Jacob, Wolfgang Schäche 11:15 Kaffeepause 11:45 Der merkwürdige Monsieur Raoul. -

Chapter 1. Jews in Viennese Popular Culture Around 1900 As Research

Chapter 1 JEWS IN VIENNESE POPULAR CULTURE AROUND 1900 AS RESEARCH TOPIC d opular culture represents a paradigmatic arena for exploring the interwove- ness and interactions between Jews and non-Jews.1 When considering the Ptopic of Jews in the realm of Viennese popular culture at the end of the nine- teenth and turn of the twentieth centuries, we must realize that this was an as- pect of history not predominantly characterized by antisemitism. To be sure, antisemitism has represented one aspect characterizing the many and various re- lationships between Jews and non-Jews. But there was also cooperation between the two that was at times more pronounced than anti-Jewish hostility. We see evidence of the juxtaposition between Judeophobia and multifaceted forms of Jewish and non-Jewish coexistence in a brief newspaper quotation from 1904. Th e topic of this quotation is the Viennese folk song, and the anonymous author states that after a long time “an authentic, sentimental song, infused with folk hu- mor, that is, an authentic Viennese folk song [Wiener Volkslied]” had fi nally once again been written. Th e song in question was “Everything Will Be Fine Again” (“Es wird ja alles wieder gut”). Martin Schenk (1860–1919) wrote the song’s lyrics, and Karl Hartl composed the tune.2 Th e quotation continues, “After . the prevalence of Yiddish and Jewish anecdotes on the Viennese stage, following the unnatural fashions that have been grafted onto Viennese folk culture and which, as fashion always does, are thoughtlessly imitated, it does one good to hear once again something authentically Viennese.”3 Th e article in which this quotation appeared indicates that the song appeared in Joseph Blaha’s publishing house. -

INFORMATION to USERS the Most Advanced Technology Has Been Used to Photo Graph and Reproduce This Manuscript from the Microfilm Master

INFORMATION TO USERS The most advanced technology has been used to photo graph and reproduce this manuscript from the microfilm master. UMI films the original text directly from the copy submitted. Thus, some dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from a computer printer. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyrighted material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are re produced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand corner and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each oversize page is available as one exposure on a standard 35 mm slide or as a 17" x 23" black and white photographic print for an additional charge. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. 35 mm slides or 6" x 9" black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. AccessingiiUM-I the World's Information since 1938 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 USA Order Number 8812304 Comrades, friends and companions: Utopian projections and social action in German literature for young people, 1926-1934 Springman, Luke, Ph.D. The Ohio State University, 1988 Copyright ©1988 by Springman, Luke. All rights reserved. UMI 300 N. Zeeb Rd. Ann Arbor, MI 48106 COMRADES, FRIENDS AND COMPANIONS: UTOPIAN PROJECTIONS AND SOCIAL ACTION IN GERMAN LITERATURE FOR YOUNG PEOPLE 1926-1934 DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of the Ohio State University By Luke Springman, B.A., M.A. -

Lange Nacht Der Museen JUNGE WILDE & ALTE MEISTER

31 AUG 13 | 18—2 UHR Lange Nacht der Museen JUNGE WILDE & ALTE MEISTER Museumsinformation Berlin (030) 24 74 98 88 www.lange-nacht-der- M u s e e n . d e präsentiert von OLD MASTERS & YOUNG REBELS Age has occupied man since the beginning of time Cranach’s »Fountain of Youth«. Many other loca- – even if now, with Europe facing an ageing popula- tions display different expression of youth culture tion and youth unemployment, it is more relevant or young artist’s protests: Mail Art in the Akademie than ever. As far back as antiquity we find unsparing der Künste, street art in the Kreuzberg Museum, depictions of old age alongside ideal figures of breakdance in the Deutsches Historisches Museum young athletes. Painters and sculptors in every and graffiti at Lustgarten. epoch have tackled this theme, demonstrating their The new additions to the Long Night programme – virtuosity in the characterisation of the stages of the Skateboard Museum, the Generation 13 muse- life. In history, each new generation has attempted um and the Ramones Museum, dedicated to the to reform society; on a smaller scale, the conflict New York punk band – especially convey the atti- between young and old has always shaped the fami- tude of a generation. There has also been a genera- ly unit – no differently amongst the ruling classes tion change in our team: Wolf Kühnelt, who came up than the common people. with the idea of the Long Night of Museums and The participating museums have creatively picked who kept it vibrant over many years, has passed on up the Long Night theme – in exhibitions, guided the management of the project.We all want to thank tours, films, talks and music.