Close-Up on the Robot of Metropolis, Fritz Lang, 1926

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ein Deutsches Nibelungen-Triptychon. Die Nibelungenfilme Und Der Deutschen Not

Jörg Hackfurth (Gießen) Ein deutsches Nibelungen-Triptychon. Die Nibelungenfilme und der Deutschen Not 1. Einleitung In From Caligari to Hitler formuliert der Soziologe Siegfried Kracauer die These, daß „mittels einer Analyse der deutschen Filme tiefenpsychologi- sche Dispositionen, wie sie in Deutschland von 1918 bis 1933 herrschten, aufzudecken sind: Dispositionen, die den Lauf der Ereignisse zu jener Zeit beeinflussen und mit denen in der Zeit nach Hitler zu rechnen sein wird".1 Kracauers analytische Methode beruht auf einigen Prämissen, die hier noch einmal in ihrem originalen Wortlaut wiedergegeben werden sollen: „Die Filme einer Nation reflektieren ihre Mentalität unvermittelter als an- dere künstlerische Medien, und das aus zwei Gründen: Erstens sind Filme niemals das Produkt eines Individuums. [...] Da jeder Filmproduktionsstab eine Mischung heterogener Interessen und Neigungen verkörpert, tendiert die Teamarbeit auf diesem Gebiet dazu, willkürliche Handhabung des Filmmaterials auszuschließen und individuelle Eigenheiten zugunsten jener zu unterdrücken, die vielen Leuten gemeinsam sind. Zweitens richten sich Filme an die anonyme Menge und sprechen sie an. Von populären Filmen [...] ist daher anzunehmen, daß sie herrschende Massenbedürfnisse befrie- digen“2 Daraus resultiert ein Mechanismus, der sowohl in Hollywood als auch in Deutschland Geltung hat: „Hollywood kann es sich nicht leisten, Sponta- neität auf Seiten des Publikums zu ignorieren. Allgemeine Unzufriedenheit zeigt sich in rückläufigen Kasseneinnahmen, und die Filmindustrie, für die Profitinteresse eine Existenzfrage ist, muß sich so weit wie möglich den Veränderungen des geistigen Klimas anpassen".3 Ferner gilt: „Was die Filme reflektieren, sind weniger explizite Überzeu- gungen als psychologische Dispositionen – jene Tiefenschichten der Kol- lektivmentalität, die sich mehr oder weniger unterhalb der Bewußtseins- dimension erstrecken. -

Xx:2 Dr. Mabuse 1933

January 19, 2010: XX:2 DAS TESTAMENT DES DR. MABUSE/THE TESTAMENT OF DR. MABUSE 1933 (122 minutes) Directed by Fritz Lang Written by Fritz Lang and Thea von Harbou Produced by Fritz Lanz and Seymour Nebenzal Original music by Hans Erdmann Cinematography by Karl Vash and Fritz Arno Wagner Edited by Conrad von Molo and Lothar Wolff Art direction by Emil Hasler and Karll Vollbrecht Rudolf Klein-Rogge...Dr. Mabuse Gustav Diessl...Thomas Kent Rudolf Schündler...Hardy Oskar Höcker...Bredow Theo Lingen...Karetzky Camilla Spira...Juwelen-Anna Paul Henckels...Lithographraoger Otto Wernicke...Kriminalkomissar Lohmann / Commissioner Lohmann Theodor Loos...Dr. Kramm Hadrian Maria Netto...Nicolai Griforiew Paul Bernd...Erpresser / Blackmailer Henry Pleß...Bulle Adolf E. Licho...Dr. Hauser Oscar Beregi Sr....Prof. Dr. Baum (as Oscar Beregi) Wera Liessem...Lilli FRITZ LANG (5 December 1890, Vienna, Austria—2 August 1976,Beverly Hills, Los Angeles) directed 47 films, from Halbblut (Half-caste) in 1919 to Die Tausend Augen des Dr. Mabuse (The Thousand Eye of Dr. Mabuse) in 1960. Some of the others were Beyond a Reasonable Doubt (1956), The Big Heat (1953), Clash by Night (1952), Rancho Notorious (1952), Cloak and Dagger (1946), Scarlet Street (1945). The Woman in the Window (1944), Ministry of Fear (1944), Western Union (1941), The Return of Frank James (1940), Das Testament des Dr. Mabuse (The Crimes of Dr. Mabuse, Dr. Mabuse's Testament, There's a good deal of Lang material on line at the British Film The Last Will of Dr. Mabuse, 1933), M (1931), Metropolis Institute web site: http://www.bfi.org.uk/features/lang/. -

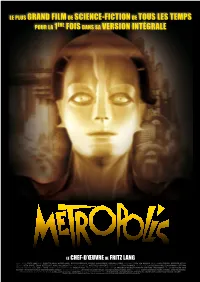

Dp-Metropolis-Version-Longue.Pdf

LE PLUS GRAND FILM DE SCIENCE-FICTION DE TOUS LES TEMPS POUR LA 1ÈRE FOIS DANS SA VERSION INTÉGRALE LE CHEf-d’œuvrE DE FRITZ LANG UN FILM DE FRITZ LANG AVEC BRIGITTE HELM, ALFRED ABEL, GUSTAV FRÖHLICH, RUDOLF KLEIN-ROGGE, HEINRICH GORGE SCÉNARIO THEA VON HARBOU PHOTO KARL FREUND, GÜNTHER RITTAU DÉCORS OTTO HUNTE, ERICH KETTELHUT, KARL VOLLBRECHT MUSIQUE ORIGINALE GOTTFRIED HUPPERTZ PRODUIT PAR ERICH POMMER. UN FILM DE LA FRIEDRICH-WILHELM-MURNAU-STIFTUNG EN COOPÉRATION AVEC ZDF ET ARTE. VENTES INTERNATIONALES TRANSIT FILM. RESTAURATION EFFECTUÉE PAR LA FRIEDRICH-WILHELM-MURNAU-STIFTUNG, WIESBADEN AVEC LA DEUTSCHE KINE MATHEK – MUSEUM FÜR FILM UND FERNSEHEN, BERLIN EN COOPÉRATION AVEC LE MUSEO DEL CINE PABLO C. DUCROS HICKEN, BUENOS AIRES. ÉDITORIAL MARTIN KOERBER, FRANK STROBEL, ANKE WILKENING. RESTAURATION DIGITAle de l’imAGE ALPHA-OMEGA DIGITAL, MÜNCHEN. MUSIQUE INTERPRÉTÉE PAR LE RUNDFUNK-SINFONIEORCHESTER BERLIN. ORCHESTRE CONDUIT PAR FRANK STROBEL. © METROPOLIS, FRITZ LANG, 1927 © FRIEDRICH-WILHELM-MURNAU-STIFTUNG / SCULPTURE DU ROBOT MARIA PAR WALTER SCHULZE-MITTENDORFF © BERTINA SCHULZE-MITTENDORFF MK2 et TRANSIT FILMS présentent LE CHEF-D’œuvre DE FRITZ LANG LE PLUS GRAND FILM DE SCIENCE-FICTION DE TOUS LES TEMPS POUR LA PREMIERE FOIS DANS SA VERSION INTEGRALE Inscrit au registre Mémoire du Monde de l’Unesco 150 minutes (durée d’origine) - format 1.37 - son Dolby SR - noir et blanc - Allemagne - 1927 SORTIE EN SALLES LE 19 OCTOBRE 2011 Distribution Presse MK2 Diffusion Monica Donati et Anne-Charlotte Gilard 55 rue Traversière 55 rue Traversière 75012 Paris 75012 Paris [email protected] [email protected] Tél. : 01 44 67 30 80 Tél. -

Film Front Weimar: Representations of the First World War in German Films from the Weimar Period (1919-1933) Kester, Bernadette

www.ssoar.info Film Front Weimar: Representations of the First World War in German Films from the Weimar Period (1919-1933) Kester, Bernadette Veröffentlichungsversion / Published Version Monographie / monograph Zur Verfügung gestellt in Kooperation mit / provided in cooperation with: OAPEN (Open Access Publishing in European Networks) Empfohlene Zitierung / Suggested Citation: Kester, B. (2002). Film Front Weimar: Representations of the First World War in German Films from the Weimar Period (1919-1933). (Film Culture in Transition). Amsterdam: Amsterdam Univ. Press. https://nbn-resolving.org/ urn:nbn:de:0168-ssoar-317059 Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Dieser Text wird unter einer CC BY-NC-ND Lizenz This document is made available under a CC BY-NC-ND Licence (Namensnennung-Nicht-kommerziell-Keine Bearbeitung) zur (Attribution-Non Comercial-NoDerivatives). For more Information Verfügung gestellt. Nähere Auskünfte zu den CC-Lizenzen finden see: Sie hier: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/deed.de * pb ‘Film Front Weimar’ 30-10-2002 14:10 Pagina 1 The Weimar Republic is widely regarded as a pre- cursor to the Nazi era and as a period in which jazz, achitecture and expressionist films all contributed to FILM FRONT WEIMAR BERNADETTE KESTER a cultural flourishing. The so-called Golden Twenties FFILMILM FILM however was also a decade in which Germany had to deal with the aftermath of the First World War. Film CULTURE CULTURE Front Weimar shows how Germany tried to reconcile IN TRANSITION IN TRANSITION the horrendous experiences of the war through the war films made between 1919 and 1933. -

Kino in Coburg

- 1 - Inhaltsverzeichnis Vorwort ................................... 3 Kinematografische Treffpunkte in Coburg ... 4 Premieren im Union-Theater ............... 10 Margarethe Birnbaum ...................... 12 Luther - Der Film (2002) ................. 14 Weitere in Coburg gedrehte Filme ......... 16 Karrierestart Coburg ..................... 18 Der Flieger (1986) ...................... 21 Rubinrot / Saphirblau .................... 22 Interview Michael Böhm ................... 25 Gästebuch Goldene Traube ................. 27 Das kleine Hofkonzert .................... 29 Jürgen A. Brückner ....................... 30 Michael Ballhaus ......................... 32 Michael Verhoeven ........................ 33 Premiere „Der blaue Strohhut“ ............ 34 Annette Hopfenmüller ...................... 36 Filmkontor Graf .......................... 37 Himmel ohne Sterne ....................... 38 Der letzte Vorhang ....................... 40 Der Abriss / Der Neubau .................. 42 Drehort Coburg · Filmkulisse Coburg ...... 44 Beruf im Wandel: Filmvorführer ........... 46 Danksagung / Impressum ................... 47 Liebe Leserinnen, liebe Leser, mit meinem Jahrgang 1968 gehöre So sahen wir den ganzen „Krieg der ich zu der Generation, die mit Sterne“-Film, von dem ein Teil mei- einem Schwarz-Weiß-Fernseher mit ner Freunde begeistert erzählt hatte. vier Programmen und ohne Fern- Mich hat dieser Film nicht beson- bedienung aufgewachsen ist. Der ders beeindruckt und ich konnte die Besuch eines Kinos war dagegen Begeisterung meiner Freunde nicht -

Page 1 of 3 Moma | Press | Releases | 1998 | Gallery Exhibition of Rare

MoMA | press | Releases | 1998 | Gallery Exhibition of Rare and Original Film Posters at ... Page 1 of 3 GALLERY EXHIBITION OF RARE AND ORIGINAL FILM POSTERS AT THE MUSEUM OF MODERN ART SPOTLIGHTS LEGENDARY GERMAN MOVIE STUDIO Ufa Film Posters, 1918-1943 September 17, 1998-January 5, 1999 The Roy and Niuta Titus Theater 1 Lobby Exhibition Accompanied by Series of Eight Films from Golden Age of German Cinema From the Archives: Some Ufa Weimar Classics September 17-29, 1998 The Roy and Niuta Titus Theater 1 Fifty posters for films produced or distributed by Ufa, Germany's legendary movie studio, will be on display in The Museum of Modern Art's Roy and Niuta Titus Theater 1 Lobby starting September 17, 1998. Running through January 5, 1999, Ufa Film Posters, 1918-1943 will feature rare and original works, many exhibited for the first time in the United States, created to promote films from Germany's golden age of moviemaking. In conjunction with the opening of the gallery exhibition, the Museum will also present From the Archives: Some Ufa Weimar Classics, an eight-film series that includes some of the studio's more celebrated productions, September 17-29, 1998. Ufa (Universumfilm Aktien Gesellschaft), a consortium of film companies, was established in the waning days of World War I by order of the German High Command, but was privatized with the postwar establishment of the Weimar republic in 1918. Pursuing a program of aggressive expansion in Germany and throughout Europe, Ufa quickly became one of the greatest film companies in the world, with a large and spectacularly equipped studio in Babelsberg, just outside Berlin, and with foreign sales that globalized the market for German film. -

Sächsisches Archivblatt Heft 1/2015

SÄCHSISCHES STAATSARCHIV Sächsisches Archivblatt Heft 1 / 2015 Inhalt Seite Jahresbericht Sächsisches Staatsarchiv 2014 1 Andrea Wettmann Aus den Beständen Grundbücher in Sachsen (Teil 2: Seit 1935) 9 Roland Pfirschke Zur audiovisuellen Überlieferung in den Abteilungen des Sächsischen Staatsarchivs (Teil 2: Chemnitz und Freiberg) 12 Stefan Gööck Leipziger Messe – Tor zur „Daten-Welt“. Messebestände elektronisch erschlossen 14 Katrin Heil/Birgit Richter Gießmannsdorf – verlorenes Land. Eine Geschichte zum Braunkohlebergbau 16 Bernd Scheperski Gottfried Huppertz – Werke des „Metropolis“-Filmkomponisten ermittelt 18 Elisabeth Veit Meldungen/Berichte „Akten – Akteure – Erinnerungen“ – Veranstaltung der BStU-Außenstelle Chemnitz zur politischen Wende von 1989 im Staatsarchiv Chemnitz 19 Raymond Plache Lagerorte auf Knopfdruck – Einführung des AUGIAS-Archiv-Magazinmoduls im Staatsarchiv Chemnitz 20 Tobias Crabus/ Yvonne Gerlach/Raymond Plache Wider besseres Wissen – Positionspapier des Umweltbundesamtes zur Archivierbarkeit von Recyclingpapier mit dem „Blauen Engel“ 24 Thomas Sergej Huck Bestandserhaltung im Staatsarchiv Chemnitz – Zusammenarbeit mit der Stadtmission Chemnitz 26 Tobias Crabus/Katja Gehmlich Sächsisches Berg- und Hüttenwesen digital 28 Angela Kugler-Kießling/Oliver Löwe Workshop des Landesverbandes Sachsen im VdA „Auf dem Weg ins Archivportal-D“ 30 Grit Richter-Laugwitz Rezensionen Matthias Donath, Rotgrüne Löwen. Die Familie von Schönberg in Sachsen 31 Jens Kunze Elke Schulze, Erich Ohser alias e. o. plauen 32 Clemens Heitmann Jahresbericht Sächsisches Staatsarchiv 2014 Der umfassende Modernisierungsprozess, 2014 Staatsarchiv Sächsisches Jahresbericht der 2005 mit der Gründung des Sächsischen Staatsarchivs begonnen und mit der Been- digung der Baumaßnahmen an vier von ins- gesamt fünf Standorten 2013 einen vorläu- figen Höhepunkt gefunden hatte, wurde im Berichtsjahr mit dem Kabinettsbericht zum Unterbringungsprogramm und mit der No- vellierung des Archivgesetzes für den Freistaat Sachsen abgeschlossen. -

Catazacke 20200425 Bd.Pdf

Provenances Museum Deaccessions The National Museum of the Philippines The Herbert F. Johnson Museum of Art, Cornell University New York, USA The Monterey Museum of Art, USA The Abrons Arts Center, New York, USA Private Estate and Collection Provenances Justus Blank, Dutch East India Company Georg Weifert (1850-1937), Federal Bank of the Kingdom of Serbia, Croatia and Slovenia Sir William Roy Hodgson (1892-1958), Lieutenant Colonel, CMG, OBE Jerrold Schecter, The Wall Street Journal Anne Marie Wood (1931-2019), Warwickshire, United Kingdom Brian Lister (19262014), Widdington, United Kingdom Léonce Filatriau (*1875), France S. X. Constantinidi, London, United Kingdom James Henry Taylor, Royal Navy Sub-Lieutenant, HM Naval Base Tamar, Hong Kong Alexandre Iolas (19071987), Greece Anthony du Boulay, Honorary Adviser on Ceramics to the National Trust, United Kingdom, Chairman of the French Porcelain Society Robert Bob Mayer and Beatrice Buddy Cummings Mayer, The Museum of Contemporary Art (MCA), Chicago Leslie Gifford Kilborn (18951972), The University of Hong Kong Traudi and Peter Plesch, United Kingdom Reinhold Hofstätter, Vienna, Austria Sir Thomas Jackson (1841-1915), 1st Baronet, United Kingdom Richard Nathanson (d. 2018), United Kingdom Dr. W. D. Franz (1915-2005), North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany Josette and Théo Schulmann, Paris, France Neil Cole, Toronto, Canada Gustav Heinrich Ralph von Koenigswald (19021982) Arthur Huc (1854-1932), La Dépêche du Midi, Toulouse, France Dame Eva Turner (18921990), DBE Sir Jeremy Lever KCMG, University -

Present and Future Urban Spaces Cinematically Considered

Exploding Spaces Present and Future Urban Spaces Cinematically Considered University of Cape Town lan-Malcolm Rijsdijk The copyright of this thesis vests in the author. No quotation from it or information derived from it is to be published without full acknowledgement of the source. The thesis is to be used for private study or non- commercial research purposes only. Published by the University of Cape Town (UCT) in terms of the non-exclusive license granted to UCT by the author. University of Cape Town [Abstract] Urban visions in contemporary film considered to be science fiction are, in fundamental ways, not extrapolations from (or even analogies with) the present, but rather derive their extrapolative impetus from the confluence of urban utopianism and the development of the film medium in the first three decades of the twentieth century. This study seeks to understand the visual dynamics of contemporary science fiction cities in film by exploring a number of diverse architectural and cinematic influences. The argument is initiated through a consideration of utopianism and science fiction, before moving onto specific architectural analysis focused on utopian plans from the modernist period, and the growth of New York during the 1920s. Through a brief reading of German Expressionist Cinema in Chapter 3, the spatial and architectural groundwork is laid for the analysis of several films in Chapters 4-6: Disclosure, Blade Runner, Selen, The Devil's Advocate, 12 Monkeys and The Fifth Element. (While not all the films would be considered as science fiction, those non-science fiction films offer provocative readings of the city as a whole). -

The Film Music of Edmund Meisel (1894–1930)

The Film Music of Edmund Meisel (1894–1930) FIONA FORD, MA Thesis submitted to The University of Nottingham for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy DECEMBER 2011 Abstract This thesis discusses the film scores of Edmund Meisel (1894–1930), composed in Berlin and London during the period 1926–1930. In the main, these scores were written for feature-length films, some for live performance with silent films and some recorded for post-synchronized sound films. The genesis and contemporaneous reception of each score is discussed within a broadly chronological framework. Meisel‘s scores are evaluated largely outside their normal left-wing proletarian and avant-garde backgrounds, drawing comparisons instead with narrative scoring techniques found in mainstream commercial practices in Hollywood during the early sound era. The narrative scoring techniques in Meisel‘s scores are demonstrated through analyses of his extant scores and soundtracks, in conjunction with a review of surviving documentation and modern reconstructions where available. ii Acknowledgements I would like to thank the Arts and Humanities Research Council (AHRC) for funding my research, including a trip to the Deutsches Filminstitut, Frankfurt. The Department of Music at The University of Nottingham also generously agreed to fund a further trip to the Deutsche Kinemathek, Berlin, and purchased several books for the Denis Arnold Music Library on my behalf. The goodwill of librarians and archivists has been crucial to this project and I would like to thank the staff at the following institutions: The University of Nottingham (Hallward and Denis Arnold libraries); the Deutsches Filminstitut, Frankfurt; the Deutsche Kinemathek, Berlin; the BFI Library and Special Collections; and the Music Librarian of the Het Brabants Orkest, Eindhoven. -

From Iron Age Myth to Idealized National Landscape: Human-Nature Relationships and Environmental Racism in Fritz Lang’S Die Nibelungen

FROM IRON AGE MYTH TO IDEALIZED NATIONAL LANDSCAPE: HUMAN-NATURE RELATIONSHIPS AND ENVIRONMENTAL RACISM IN FRITZ LANG’S DIE NIBELUNGEN Susan Power Bratton Whitworth College Abstract From the Iron Age to the modern period, authors have repeatedly restructured the ecomythology of the Siegfried saga. Fritz Lang’s Weimar lm production (released in 1924-1925) of Die Nibelungen presents an ascendant humanist Siegfried, who dom- inates over nature in his dragon slaying. Lang removes the strong family relation- ships typical of earlier versions, and portrays Siegfried as a son of the German landscape rather than of an aristocratic, human lineage. Unlike The Saga of the Volsungs, which casts the dwarf Andvari as a shape-shifting sh, and thereby indis- tinguishable from productive, living nature, both Richard Wagner and Lang create dwarves who live in subterranean or inorganic habitats, and use environmental ideals to convey anti-Semitic images, including negative contrasts between Jewish stereo- types and healthy or organic nature. Lang’s Siegfried is a technocrat, who, rather than receiving a magic sword from mystic sources, begins the lm by fashioning his own. Admired by Adolf Hitler, Die Nibelungen idealizes the material and the organic in a way that allows the modern “hero” to romanticize himself and, with- out the aid of deities, to become superhuman. Introduction As one of the great gures of Weimar German cinema, Fritz Lang directed an astonishing variety of lms, ranging from the thriller, M, to the urban critique, Metropolis. 1 Of all Lang’s silent lms, his two part interpretation of Das Nibelungenlied: Siegfried’s Tod, lmed in 1922, and Kriemhilds Rache, lmed in 1923,2 had the greatest impression on National Socialist leaders, including Adolf Hitler. -

Heng-Moduleawk7-Metropolis.Pdf

Phone: (02) 8007 6824 DUX Email: [email protected] Web: dc.edu.au 2018 HIGHER SCHOOL CERTIFICATE COURSE MATERIALS HSC English Advanced Module A: Metropolis Term 1 – Week 7 Name ………………………………………………………. Class day and time ………………………………………… Teacher name ……………………………………………... HSC English Advanced - Module A: Metropolis Term 1 – Week 7 1 DUX Term 1 – Week 7 – Theory • Film Analysis • Homework FILM ANALYSIS SEGMENT SIX (THE MACHINE-MAN) After discovering the workers' clandestine meeting, Freder's controlling, glacial father conspires with mad scientist Rotwang to create an evil, robotic Maria duplicate, in order to manipulate his workers and preach riot and rebellion. Fredersen could then use force against his rebellious workers that would be interpreted as justified, causing their self-destruction and elimination. Ultimately, robots would be capable of replacing the human worker, but for the time being, the robot would first put a stop to their revolutionary activities led by the good Maria: "Rotwang, give the Machine-Man the likeness of that girl. I shall sow discord between them and her! I shall destroy their belief in this woman --!" After Joh Fredersen leaves to return above ground, Rotwang predicts doom for Joh's son, knowing that he will be the workers' mediator against his own father: "You fool! Now you will lose the one remaining thing you have from Hel - your son!" Rotwang comes out of hiding, and confronts Maria, who is now alone deep in the catacombs (with open graves and skeletal remains surrounding her). He pursues her - in the expressionistic scene, he chases her with the beam of light from his bright flashlight, then corners her, and captures her when she cannot escape at a dead-end.